Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Orangeburg, South Carolina

Overview >> South Carolina >> Orangeburg

Orangeburg: Historical Overview

In 1705, an Indian trader named George Sterling settled along the Edisto River in central South Carolina. Seeking to encourage migration to the area, the colony’s government made the area into a township in 1730. By 1735, a group of German-Swiss immigrants had arrived at the Indian trading center called Edisto. Deciding to settle there, the group changed the village’s name to Orangeburgh, in honor of William of Orange.

Situated on hilly ground by the Edisto River, Orangeburgh village was soon surrounded by a well-populated farming region. The Orangeburgh District’s cotton production helped to make many 19th century farmers wealthy and, in tandem with the railroads, contributed to the area’s growth. While Orangeburgh was not spared by General Sherman on his march through the state at the end of the Civil War, the town soon recovered. After the war, Orangeburg dropped the “h” at the end of its name and was incorporated as a city. Cotton farming continued to be Orangeburg County’s economic mainstay, supplemented by other crops such as corn, wheat, rice, potatoes, pecans, and peanuts.

After the village with a population less than 400 was connected to Charleston and Columbia via rail in the early 1840s, Orangeburg’s population doubled in less than ten years. German Jews, such as Theodore Kohn, were among the settlers drawn to the area.

The Jewish community has been a small but vibrant part of Orangeburg from the 19th century to the present day.

Situated on hilly ground by the Edisto River, Orangeburgh village was soon surrounded by a well-populated farming region. The Orangeburgh District’s cotton production helped to make many 19th century farmers wealthy and, in tandem with the railroads, contributed to the area’s growth. While Orangeburgh was not spared by General Sherman on his march through the state at the end of the Civil War, the town soon recovered. After the war, Orangeburg dropped the “h” at the end of its name and was incorporated as a city. Cotton farming continued to be Orangeburg County’s economic mainstay, supplemented by other crops such as corn, wheat, rice, potatoes, pecans, and peanuts.

After the village with a population less than 400 was connected to Charleston and Columbia via rail in the early 1840s, Orangeburg’s population doubled in less than ten years. German Jews, such as Theodore Kohn, were among the settlers drawn to the area.

The Jewish community has been a small but vibrant part of Orangeburg from the 19th century to the present day.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Orangeburg

Orangeburg's Jewish cemetery.

Orangeburg's Jewish cemetery. Photo by Dale Rosengarten

The Kohn Family

Theodore Kohn arrived in Orangeburg in 1850 as a young man after emigrating from Bavaria with his parents and brother. He served in the Edisto Rifles during the Civil War, signing on at the outbreak of hostilities. When he first arrived in Orangeburg, Kohn worked for his uncle, Deopold Louis, an established merchant and possibly the earliest Jewish settler in town. In 1868, Kohn and a friend opened a general merchandise store, Ezekial and Kohn. Their association appears to have been brief, however, since Kohn’s brother Henry joined him in a mercantile business, Theodore Kohn and Brother, the following year. At some point, Henry left to open his own store.

Theodore became a respected businessman and an important civic leader in Orangeburg. He was an alderman, a founding member of Edisto Bank, and was credited with being the primary force behind the creation of Orangeburg’s public schools. Dubbed the “Father of Orangeburg graded schools,” Theodore was also a member of the Shibboleth Lodge, serving as its treasurer for more than two decades.

Theodore Kohn’s store survived into the 20th century, run by Theodore’s son Sol. Later it became Kohn-Kahnweiler, owned by Bertram Kahnweiler, a transplant from Montana who married Theodore’s daughter. Kahnweiler started out as a pharmacist and expanded into retail clothing. In 1929, he sold “drugs, sundries, and specialties,” and clothing for “women of fashion” at discounted prices. Aware that his store was not in the high rent district, he made a point of its location with his motto, “Two Minutes Walk to the Style Center of Orangeburg.” Bertram’s wife Bertha and her sister, Adelina Kohn, took over the reins when he died in 1933.

Henry Kohn made his mark on the community as well. He was a founder of the Young America Fire Company and a Mason. His most significant contribution, in partnership with his wife, Matilda Baum Kohn, was their organization and leadership of the Orangeburg Philharmonic Orchestra. They directed the group of amateur musicians for approximately 50 years. Henry, himself a violinist and a violin instructor, was admired for his devotion to bringing music to the city.

Theodore Kohn arrived in Orangeburg in 1850 as a young man after emigrating from Bavaria with his parents and brother. He served in the Edisto Rifles during the Civil War, signing on at the outbreak of hostilities. When he first arrived in Orangeburg, Kohn worked for his uncle, Deopold Louis, an established merchant and possibly the earliest Jewish settler in town. In 1868, Kohn and a friend opened a general merchandise store, Ezekial and Kohn. Their association appears to have been brief, however, since Kohn’s brother Henry joined him in a mercantile business, Theodore Kohn and Brother, the following year. At some point, Henry left to open his own store.

Theodore became a respected businessman and an important civic leader in Orangeburg. He was an alderman, a founding member of Edisto Bank, and was credited with being the primary force behind the creation of Orangeburg’s public schools. Dubbed the “Father of Orangeburg graded schools,” Theodore was also a member of the Shibboleth Lodge, serving as its treasurer for more than two decades.

Theodore Kohn’s store survived into the 20th century, run by Theodore’s son Sol. Later it became Kohn-Kahnweiler, owned by Bertram Kahnweiler, a transplant from Montana who married Theodore’s daughter. Kahnweiler started out as a pharmacist and expanded into retail clothing. In 1929, he sold “drugs, sundries, and specialties,” and clothing for “women of fashion” at discounted prices. Aware that his store was not in the high rent district, he made a point of its location with his motto, “Two Minutes Walk to the Style Center of Orangeburg.” Bertram’s wife Bertha and her sister, Adelina Kohn, took over the reins when he died in 1933.

Henry Kohn made his mark on the community as well. He was a founder of the Young America Fire Company and a Mason. His most significant contribution, in partnership with his wife, Matilda Baum Kohn, was their organization and leadership of the Orangeburg Philharmonic Orchestra. They directed the group of amateur musicians for approximately 50 years. Henry, himself a violinist and a violin instructor, was admired for his devotion to bringing music to the city.

The Brown Family

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a number of Jews settled in the towns surrounding Orangeburg, such as Bowman, Branchville, St. Matthews, Elloree, Eutawville, and Blackville. Many of the newcomers were landsmen, hailing from the same part of the Old Country, or were linked by marriage. Simon Brown, a shoemaker, immigrated to the United States from what is now Poland around 1849 with his wife, Philapena Asher Brown, a Jew of Sephardic descent. Initially, they joined Pena’s brothers in New Jersey, but left the state after Simon became involved with anarchists. For reasons unknown, the Browns chose to settle in Blackville, which was home to approximately 40 Jews by 1878. During the Civil War, Simon Brown fought in the Confederate Army. Although there was no Jewish congregation in the area, he was committed to preserving his family’s Jewishness, sending his children by train to the Sunday school at the Reform temple in Augusta, Georgia. He and Pena were buried in Augusta’s Jewish cemetery.

How long Simon continued in the shoemaking trade in Blackville is unclear, but at some point he opened a store called Simon Brown’s Sons, touting “Globo de Oro—the New Golden Centered Cantaloupe” among the goods for sale. He also became a substantial landowner and, according to one descendant, owned slaves in the years before the Civil War. By the time of his death in 1906, he had acquired 5,000 acres.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a number of Jews settled in the towns surrounding Orangeburg, such as Bowman, Branchville, St. Matthews, Elloree, Eutawville, and Blackville. Many of the newcomers were landsmen, hailing from the same part of the Old Country, or were linked by marriage. Simon Brown, a shoemaker, immigrated to the United States from what is now Poland around 1849 with his wife, Philapena Asher Brown, a Jew of Sephardic descent. Initially, they joined Pena’s brothers in New Jersey, but left the state after Simon became involved with anarchists. For reasons unknown, the Browns chose to settle in Blackville, which was home to approximately 40 Jews by 1878. During the Civil War, Simon Brown fought in the Confederate Army. Although there was no Jewish congregation in the area, he was committed to preserving his family’s Jewishness, sending his children by train to the Sunday school at the Reform temple in Augusta, Georgia. He and Pena were buried in Augusta’s Jewish cemetery.

How long Simon continued in the shoemaking trade in Blackville is unclear, but at some point he opened a store called Simon Brown’s Sons, touting “Globo de Oro—the New Golden Centered Cantaloupe” among the goods for sale. He also became a substantial landowner and, according to one descendant, owned slaves in the years before the Civil War. By the time of his death in 1906, he had acquired 5,000 acres.

St. Matthews

St. Matthews, originally known as Lewisville, attracted a handful of Jewish families in the latter half of the 19th century. In 1878, six years after its incorporation, the town was home to an estimated 19 Jewish residents. Jewish businessmen in 1889 included M. Jarecky, J. H. Loryea, and P. Rich. Brothers Moritz and Lipman Rich of Germany settled in Charleston first before moving to St. Matthews after the Civil War. Moritz’s grandson Lipman P. Rich, who was born in 1894 in St. Matthews, moved to Orangeburg with his wife and daughter and opened a clothing store. After the business failed during the Depression, Lipman went to work for the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.

St. Matthews, originally known as Lewisville, attracted a handful of Jewish families in the latter half of the 19th century. In 1878, six years after its incorporation, the town was home to an estimated 19 Jewish residents. Jewish businessmen in 1889 included M. Jarecky, J. H. Loryea, and P. Rich. Brothers Moritz and Lipman Rich of Germany settled in Charleston first before moving to St. Matthews after the Civil War. Moritz’s grandson Lipman P. Rich, who was born in 1894 in St. Matthews, moved to Orangeburg with his wife and daughter and opened a clothing store. After the business failed during the Depression, Lipman went to work for the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.

The Community Grows

During the early 20th century, the Jewish population of Orangeburg grew as Eastern European Jews joined the earlier German settlers. By 1905, an estimated 60 Jews lived in Orangeburg. Most of them owned stores, including the Abrams, Beckers, Bernsteins, Finkelsteins, Furchgotts, Hurwitzs, Levines, Manheims, Marcuses, Mirmows, Rubensteins, Silvers, and Wilinskys.

Small towns across the region also attracted Jewish shopkeepers. Nathan Blatt, while peddling out of Charleston, learned that Blackville was ripe for a new merchant and decided to set up shop there. Jewish stores in the region included Alexander Goldiner ran a store in St. Matthews, the Nussbaums in Branchville, the Nesses in Denmark, and the Pearlstines in St. Matthews, Branchville, and Olar. Louis Link, who was born in St. Matthews and raised in Orangeburg, became a peddler. His father Solomon, a Russian immigrant, had been an Orangeburg merchant in the late 1800s. Joseph J. Miller of Elloree and Mordie Rubenstein of Orangeburg, competitors and good friends who often ate lunch together, each ran a store in Elloree.

During the early 20th century, the Jewish population of Orangeburg grew as Eastern European Jews joined the earlier German settlers. By 1905, an estimated 60 Jews lived in Orangeburg. Most of them owned stores, including the Abrams, Beckers, Bernsteins, Finkelsteins, Furchgotts, Hurwitzs, Levines, Manheims, Marcuses, Mirmows, Rubensteins, Silvers, and Wilinskys.

Small towns across the region also attracted Jewish shopkeepers. Nathan Blatt, while peddling out of Charleston, learned that Blackville was ripe for a new merchant and decided to set up shop there. Jewish stores in the region included Alexander Goldiner ran a store in St. Matthews, the Nussbaums in Branchville, the Nesses in Denmark, and the Pearlstines in St. Matthews, Branchville, and Olar. Louis Link, who was born in St. Matthews and raised in Orangeburg, became a peddler. His father Solomon, a Russian immigrant, had been an Orangeburg merchant in the late 1800s. Joseph J. Miller of Elloree and Mordie Rubenstein of Orangeburg, competitors and good friends who often ate lunch together, each ran a store in Elloree.

Office Holders

Like small town Jewish store owners in other parts of the state, midlands merchants tried hard to integrate into society and often attained elected office. Harry N. Marcus, for example, was mayor of his hometown, Eutawville, from the late 1940s to the early 1970s. The World War II veteran was a Mason, a Shriner, and owner of Marcus Department Store, a business started by his father in the first half of the 20th century. Irving Benjamin, who owned a department store in Bowman, served for 30 years as a councilman, and was a member of the Masons and the American Legion.

Like small town Jewish store owners in other parts of the state, midlands merchants tried hard to integrate into society and often attained elected office. Harry N. Marcus, for example, was mayor of his hometown, Eutawville, from the late 1940s to the early 1970s. The World War II veteran was a Mason, a Shriner, and owner of Marcus Department Store, a business started by his father in the first half of the 20th century. Irving Benjamin, who owned a department store in Bowman, served for 30 years as a councilman, and was a member of the Masons and the American Legion.

Jewish Businesses

Jews in the region owned other types of businesses as well as stores. The Jareckys and Sol Wetherhorn were cotton factors in St. Matthews. H. M. Kline was a junk and used car parts dealer. Evelyn Marcus practiced law in her hometown of Orangeburg, after becoming the first woman in the county to be admitted to the bar in 1920. Evelyn’s choice of a professional career was a harbinger of the path future generations of Jews from Orangeburg and its neighboring small towns would take. The Jewish-owned stores on the main streets of the midlands would gradually close their doors as the owners retired with no one in the next generation to stand behind the till. One resident, born in Orangeburg in 1922, reported that the Jewish population in town had peaked in the early 1900s and was in decline when her generation was coming of age. In 1996, Barshay and Marcus Clothing Store, the sole remaining Jewish-owned store in Orangeburg, closed its doors.

Jews in the region owned other types of businesses as well as stores. The Jareckys and Sol Wetherhorn were cotton factors in St. Matthews. H. M. Kline was a junk and used car parts dealer. Evelyn Marcus practiced law in her hometown of Orangeburg, after becoming the first woman in the county to be admitted to the bar in 1920. Evelyn’s choice of a professional career was a harbinger of the path future generations of Jews from Orangeburg and its neighboring small towns would take. The Jewish-owned stores on the main streets of the midlands would gradually close their doors as the owners retired with no one in the next generation to stand behind the till. One resident, born in Orangeburg in 1922, reported that the Jewish population in town had peaked in the early 1900s and was in decline when her generation was coming of age. In 1996, Barshay and Marcus Clothing Store, the sole remaining Jewish-owned store in Orangeburg, closed its doors.

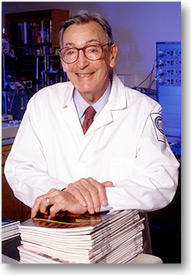

Nobel Prize winner Robert Furchgott

Nobel Prize winner Robert Furchgott

Organized Jewish Life in Orangeburg

Although their numbers were relatively small, Orangeburg’s Jews tried to maintain their religious traditions. The first Jewish organization in Orangeburg, the Hebrew Benevolent Society, was organized in 1885 with Theodore Kohn acting as president. The group purchased land for a cemetery the following year. In 1904, Orangeburg Jews officially founded a congregation, with Henry Kohn serving as its president. Its name is uncertain; the 1907 American Jewish Year Book called it “Beth Israel,” but in 1918, they called themselves “B'rith Sholim.” That year, they held a confirmation service at which Rabbi Jacob Raisin of Charleston’s Reform congregation Beth Elohim officiated; Raisin helped to run the school and was listed in the program as “superintendant.” In 1918, they had 14 students in their religious school, which met weekly, even as the congregation met only twice a month for religious services. Orangeburg had an estimated Jewish population of 59 at the time. By 1925, the Orangeburg congregation had affiliated with the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations and had 20 contributing members.

During the Great Depression, the community and the congregation went into decline. While 88 Jews lived in Orangeburg in 1927, only 48 lived there a decade later. Robert Furchgott, who received the Nobel Prize for Biochemistry in 1998, moved from Charleston to Orangeburg with his family in 1929 when he was 13. His mother, Philapena Sorentrue, was from Orangeburg. His father, Arthur, who had struggled to make a living in Charleston, ran a store in Orangeburg until the mid-1930s when the family moved again. Furchgott recalled his father meeting with other Jews on Saturdays to hold services “in some sort of a public building.” The number of participants must have been small, as Robert believed there were only five or six Jewish families living in the city at the time. A visiting rabbi came to town to conduct services once a month. The congregants followed the Reform tradition and offered Sunday school classes, with Kate Marcus instructing, even as the number of children in the school was dropping. Indeed, Robert and his cousin Edward Moseley were part of the last confirmation class in Orangeburg. Rabbi Samuel R. Shillman of Sumter officiated at this final ceremony. During the 1930s, the religious school disbanded.

The religious practices of Orangeburg Jews tended to be fairly relaxed. Observant Jews typically traveled to Charleston or Columbia for the High Holy Days. Some families simply conducted services at home. Edward V. Mirmow, Jr., born in 1930 in Orangeburg, attended Sunday school sporadically and for a short time only; for some reason, he reported, “it didn’t last.” Mirmow estimated that as much as half the Jewish population did not attend worship services. Others, often through intermarriage, became practicing Christians.

Although their numbers were relatively small, Orangeburg’s Jews tried to maintain their religious traditions. The first Jewish organization in Orangeburg, the Hebrew Benevolent Society, was organized in 1885 with Theodore Kohn acting as president. The group purchased land for a cemetery the following year. In 1904, Orangeburg Jews officially founded a congregation, with Henry Kohn serving as its president. Its name is uncertain; the 1907 American Jewish Year Book called it “Beth Israel,” but in 1918, they called themselves “B'rith Sholim.” That year, they held a confirmation service at which Rabbi Jacob Raisin of Charleston’s Reform congregation Beth Elohim officiated; Raisin helped to run the school and was listed in the program as “superintendant.” In 1918, they had 14 students in their religious school, which met weekly, even as the congregation met only twice a month for religious services. Orangeburg had an estimated Jewish population of 59 at the time. By 1925, the Orangeburg congregation had affiliated with the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations and had 20 contributing members.

During the Great Depression, the community and the congregation went into decline. While 88 Jews lived in Orangeburg in 1927, only 48 lived there a decade later. Robert Furchgott, who received the Nobel Prize for Biochemistry in 1998, moved from Charleston to Orangeburg with his family in 1929 when he was 13. His mother, Philapena Sorentrue, was from Orangeburg. His father, Arthur, who had struggled to make a living in Charleston, ran a store in Orangeburg until the mid-1930s when the family moved again. Furchgott recalled his father meeting with other Jews on Saturdays to hold services “in some sort of a public building.” The number of participants must have been small, as Robert believed there were only five or six Jewish families living in the city at the time. A visiting rabbi came to town to conduct services once a month. The congregants followed the Reform tradition and offered Sunday school classes, with Kate Marcus instructing, even as the number of children in the school was dropping. Indeed, Robert and his cousin Edward Moseley were part of the last confirmation class in Orangeburg. Rabbi Samuel R. Shillman of Sumter officiated at this final ceremony. During the 1930s, the religious school disbanded.

The religious practices of Orangeburg Jews tended to be fairly relaxed. Observant Jews typically traveled to Charleston or Columbia for the High Holy Days. Some families simply conducted services at home. Edward V. Mirmow, Jr., born in 1930 in Orangeburg, attended Sunday school sporadically and for a short time only; for some reason, he reported, “it didn’t last.” Mirmow estimated that as much as half the Jewish population did not attend worship services. Others, often through intermarriage, became practicing Christians.

Civic Engagement

The ease and frequency with which intermarriage occurred in Orangeburg reflects both the paltry number of potential Jewish spouses in the area as well as the close social relationships Jews enjoyed with non-Jews. Jews were full participants in the social life and civic affairs of Orangeburg, belonging to numerous non-Jewish social and service clubs. The life and death of Joseph Miller reflected this civic involvement and interfaith harmony. Born in Philadelphia, he came to Elloree in 1946 by way of Augusta and Sumter, and bought a department store. Upon his retirement in 1973, he established the Joseph J. Miller Foundation to support “religious, scientific, literary or educational charities.” He had no living relatives when he died in 1980, and in his will, left his estate to four Elloree churches, Orangeburg’s Temple Sinai, Charleston’s Brith Sholom Beth Israel, the Savannah Hebrew Day School, and various charities.

Jews were an integral and well integrated part of the Orangeburg community, adapting to local cultural mores. Edward Mirmow, born in New York City to Russian immigrants, moved with his family to Orangeburg in 1901 when he was a year old. He lettered in football and baseball at the University of South Carolina and remained a big Gamecocks fan throughout his life. Eddie shared his love of sports with his fellow citizens in Orangeburg. After World War II, he organized and served for ten years as the athletic director for the city’s American Legion baseball program. Mirmow Field was named in his honor in 1948. Eddie’s leadership in promoting sports led him to set a precedent for other communities when he founded the Orangeburg Indian Boosters Club with the purpose of supporting high school athletics.

The ease and frequency with which intermarriage occurred in Orangeburg reflects both the paltry number of potential Jewish spouses in the area as well as the close social relationships Jews enjoyed with non-Jews. Jews were full participants in the social life and civic affairs of Orangeburg, belonging to numerous non-Jewish social and service clubs. The life and death of Joseph Miller reflected this civic involvement and interfaith harmony. Born in Philadelphia, he came to Elloree in 1946 by way of Augusta and Sumter, and bought a department store. Upon his retirement in 1973, he established the Joseph J. Miller Foundation to support “religious, scientific, literary or educational charities.” He had no living relatives when he died in 1980, and in his will, left his estate to four Elloree churches, Orangeburg’s Temple Sinai, Charleston’s Brith Sholom Beth Israel, the Savannah Hebrew Day School, and various charities.

Jews were an integral and well integrated part of the Orangeburg community, adapting to local cultural mores. Edward Mirmow, born in New York City to Russian immigrants, moved with his family to Orangeburg in 1901 when he was a year old. He lettered in football and baseball at the University of South Carolina and remained a big Gamecocks fan throughout his life. Eddie shared his love of sports with his fellow citizens in Orangeburg. After World War II, he organized and served for ten years as the athletic director for the city’s American Legion baseball program. Mirmow Field was named in his honor in 1948. Eddie’s leadership in promoting sports led him to set a precedent for other communities when he founded the Orangeburg Indian Boosters Club with the purpose of supporting high school athletics.

Temple Sinai dedicated its synagogue in 1956.

Temple Sinai dedicated its synagogue in 1956. Photo by Dale Rosengarten

Temple Sinai

After World War II, the area’s Jewish community was revitalized. By 1960, 120 Jews lived in Orangeburg County. In the 1950s, they reorganized the congregation, adopting the name Temple Sinai. The impetus was the desire to build a synagogue, something their Christian friends and neighbors helped to make possible by donating to the building fund. The temple, which was completed and dedicated in early 1956, seats 100 in the sanctuary and includes a kitchen and Sunday school rooms on the lower level. Sunday school classes were held during the temple’s early years, serving the small number of young families who were part of the post-World War II baby boom. J. J. Teskey, who had moved to Orangeburg from Savannah, served as president of the board of directors and lay leader during services. Member families, many of whom had young children at the time, hailed not just from Orangeburg, but from the surrounding towns as well. Membership consisted of 15 to 20 families during this peak period.

Temple Sinai never had its own rabbi, although they brought in student rabbis for High Holy Day services. Until he retired, Rabbi David Gruber of Columbia’s Tree of Life Synagogue came once a month to conduct worship services. This post-war peak of Jewish activity was fleeting, as the congregation declined again at the end of the 20th century. Disagreements over whether to use the Reform or Conservative prayer book weakened the congregation. Temple Sinai’s existence became more tenuous as the children left for college and settled elsewhere.

After World War II, the area’s Jewish community was revitalized. By 1960, 120 Jews lived in Orangeburg County. In the 1950s, they reorganized the congregation, adopting the name Temple Sinai. The impetus was the desire to build a synagogue, something their Christian friends and neighbors helped to make possible by donating to the building fund. The temple, which was completed and dedicated in early 1956, seats 100 in the sanctuary and includes a kitchen and Sunday school rooms on the lower level. Sunday school classes were held during the temple’s early years, serving the small number of young families who were part of the post-World War II baby boom. J. J. Teskey, who had moved to Orangeburg from Savannah, served as president of the board of directors and lay leader during services. Member families, many of whom had young children at the time, hailed not just from Orangeburg, but from the surrounding towns as well. Membership consisted of 15 to 20 families during this peak period.

Temple Sinai never had its own rabbi, although they brought in student rabbis for High Holy Day services. Until he retired, Rabbi David Gruber of Columbia’s Tree of Life Synagogue came once a month to conduct worship services. This post-war peak of Jewish activity was fleeting, as the congregation declined again at the end of the 20th century. Disagreements over whether to use the Reform or Conservative prayer book weakened the congregation. Temple Sinai’s existence became more tenuous as the children left for college and settled elsewhere.

The Jewish Community in Orangeburg Today

Today, only three or four members meet one Saturday morning a month for worship led by a lay reader. Somehow, the tiny congregation is able to maintain its synagogue building. High Holy Day services are a “hit or miss proposition,” according to one member. In the near future, Temple Sinai will likely face the same fate as the now closed Jewish-owned stores that once lined the streets of Orangeburg and its surrounding towns.