Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Spartanburg, South Carolina

Overview >> South Carolina >> Spartanburg

Spartanburg: Historical Overview

|

Spartanburg, located in the foothills of the Appalachians, was built on agriculture and textile manufacturing in a region acquired by treaty from the Cherokees in the mid-1700s. Named the county seat in 1785, the upcountry village grew slowly in the ensuing decades. By the 1850s however, the downtown district was booming with newly established businesses as merchants and professionals moved to the city, made more attractive by the establishment of Wofford College and more accessible by a new railroad connection to Columbia.

An estimated nine Jews lived in Spartanburg in 1878. Their identities have not been determined and they may not have been the first to settle there. It seems likely that Jews would have been among the antebellum residents of Spartanburg, as they were in nearby Greenville. The Jewish community today remains a vibrant part of life in Spartanburg. |

RESOURCES

Congregation B'nai Israel website All photos courtesy of Special Collections, College of Charleston |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Spartanburg

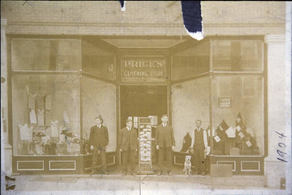

Price's Cothing Store, circa 1904

Price's Cothing Store, circa 1904

Early Jewish Residents

In 1886, Moses Greenewald opened the first Jewish-owned store in Spartanburg, called “M. Greenewald, Outfitters to Men and Boys.” He was living in Spartanburg, however, at least by 1882, when he served as captain of the volunteer Spartan Fire Engine Company. Moses was the first of four brothers to move to Spartanburg from Wilmington, North Carolina. David Greenewald arrived in the late 1880s. An Elks Club member, he was a director of the Chamber of Commerce and the Spartanburg Music Festival. Isaac and Max joined their older brothers a decade or so later. Both were musicians and co-managed the Spartanburg Opera House, informally referred to as Greenewald’s Opera House.

With the expansion of the textile industry, Spartanburg’s general population increased dramatically between 1890 and 1920. The city was a leading producer of cotton in South Carolina. The Jewish population began to grow appreciably after the turn of the 20th century. Harry Price, grandson of a Lithuanian immigrant, moved to Spartanburg from New York City on the advice of his brother-in-law who lived in Hartwell, Georgia. In 1903, he opened The New York Bazaar, later renamed Price’s Clothing Store, next to Greenewald’s. A few years later, he married Dora Mann of Newberry, South Carolina, in a ceremony conducted by Rabbi David Karesh, spiritual leader of Columbia’s Orthodox House of Peace. Harry, like the Greenewalds, was actively engaged in civic affairs. He was a member of the Knights of Pythias, the Woodmen of the World, the Loyal Order of the Moose, and the Chamber of Commerce.

Dr. L. Rosa Hirschmann, a South Carolina native, began practicing medicine in Spartanburg in 1903, two years after graduating from the Medical College of South Carolina. One of the college’s first two female graduates, she was Spartanburg’s first female physician. Rosa married Robert J. Gantt, an attorney, in 1905, and continued her work as an ear, nose, and throat specialist until her death in 1935.

David and Joseph (Joel) Spigel of Prussia peddled in Columbia and Newberry before settling in Spartanburg, also in 1903. The brothers opened a small store that sold jewelry and eyeglasses. Other turn of the century arrivals included the Brill, Hecklin, Morris, Cohen, and Ougust (August) families—all dry goods merchants.

In 1886, Moses Greenewald opened the first Jewish-owned store in Spartanburg, called “M. Greenewald, Outfitters to Men and Boys.” He was living in Spartanburg, however, at least by 1882, when he served as captain of the volunteer Spartan Fire Engine Company. Moses was the first of four brothers to move to Spartanburg from Wilmington, North Carolina. David Greenewald arrived in the late 1880s. An Elks Club member, he was a director of the Chamber of Commerce and the Spartanburg Music Festival. Isaac and Max joined their older brothers a decade or so later. Both were musicians and co-managed the Spartanburg Opera House, informally referred to as Greenewald’s Opera House.

With the expansion of the textile industry, Spartanburg’s general population increased dramatically between 1890 and 1920. The city was a leading producer of cotton in South Carolina. The Jewish population began to grow appreciably after the turn of the 20th century. Harry Price, grandson of a Lithuanian immigrant, moved to Spartanburg from New York City on the advice of his brother-in-law who lived in Hartwell, Georgia. In 1903, he opened The New York Bazaar, later renamed Price’s Clothing Store, next to Greenewald’s. A few years later, he married Dora Mann of Newberry, South Carolina, in a ceremony conducted by Rabbi David Karesh, spiritual leader of Columbia’s Orthodox House of Peace. Harry, like the Greenewalds, was actively engaged in civic affairs. He was a member of the Knights of Pythias, the Woodmen of the World, the Loyal Order of the Moose, and the Chamber of Commerce.

Dr. L. Rosa Hirschmann, a South Carolina native, began practicing medicine in Spartanburg in 1903, two years after graduating from the Medical College of South Carolina. One of the college’s first two female graduates, she was Spartanburg’s first female physician. Rosa married Robert J. Gantt, an attorney, in 1905, and continued her work as an ear, nose, and throat specialist until her death in 1935.

David and Joseph (Joel) Spigel of Prussia peddled in Columbia and Newberry before settling in Spartanburg, also in 1903. The brothers opened a small store that sold jewelry and eyeglasses. Other turn of the century arrivals included the Brill, Hecklin, Morris, Cohen, and Ougust (August) families—all dry goods merchants.

B'nai Israel's first synagogue later became a Baptist Church.

B'nai Israel's first synagogue later became a Baptist Church.

Organized Jewish Life in Spartanburg

Members of today’s congregation believe that there were enough observant Jews in town by 1905 to form a minyan. Although this date is cited as the beginning of Spartanburg’s “active Jewish community,” the Carolina Spartan made note of the city’s “Hebrew friends” meeting for Yom Kippur in its September 1888 issue. In 1912, the small congregation of perhaps a dozen families drafted a constitution and bylaws and, two years later, the city directory recorded the meeting place of Sirh Israel Congregation as the same address as Abe Goldberg’s clothing store on West Main Street. Reverend Craft, an itinerant rabbi, conducted holiday services until members hired Samuel Cohen, an Orthodox rabbi born in Russia, who served from 1914 to 1916, when he died unexpectedly.

In 1916, the group of roughly 27 members, represented by Joel Spigel, Hyman Ougust, and Joseph Miller filed for incorporation, adopting the name B’nai Israel. Max Cohen served as president, Isaac Greenewald as treasurer, and Harry Price as secretary. That same year, Rabbi Jacob Raisin of Charleston’s Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim visited Spartanburg to “inspire a fund-raising effort.” Sunday school classes, organized by founding member Joseph Jacobs, were hosted by Mrs. I. Fuchtler in her living room until a synagogue was built in 1917 at the corner of Dean and Union Streets. The Ladies Auxiliary, led by its first president, Dr. Rosa Hirschmann Gantt, raised funds for stained glass windows and pews for a congregation that had doubled in size in just five years. The Spartanburg Herald noted that the new synagogue was open in time for High Holy Days services in 1917, and that both Reform and Orthodox traditions were practiced, at least during the holidays. Reform members observes one day under the leadership of Dr. Finklestein, with services in English, while Orthodox members celebrated both days with Dr. Isaiah Sobell, who conducted services in Hebrew.

The size of the Jewish community fluctuated during the 1920s and 1930s. Some merchants left, while a few of those who remained closed due to bankruptcy, both before and during the Great Depression. The population, estimated at 80 in 1927, nevertheless, was substantial enough to warrant a cemetery. In 1924, Rosa Gantt was instrumental in establishing a Jewish burial ground in a section of Spartanburg’s Oakwood Cemetery. Furthermore, the vitality of the congregation helped it to survive the economic hardships of the 1930s. Its 36 members reportedly maintained their rabbinical leadership throughout the Depression and, in 1937, Joseph Spigel paid off the mortgage. Spigel, who had been chairman of the building committee for the Dean Street synagogue, died that year on the same day as his good friend, Harry Price. By 1937, 98 Jews lived in Spartanburg.

David Spigel, Joseph’s younger brother, died 12 years later, leaving large bequests to Spartanburg’s Children’s Hospital and B’nai Israel. The gift to the congregation was designated for building improvements, including a new bimah and ark. His estate also provided funds to the Columbia Hebrew Benevolent Society for those needing burial assistance.

Members of today’s congregation believe that there were enough observant Jews in town by 1905 to form a minyan. Although this date is cited as the beginning of Spartanburg’s “active Jewish community,” the Carolina Spartan made note of the city’s “Hebrew friends” meeting for Yom Kippur in its September 1888 issue. In 1912, the small congregation of perhaps a dozen families drafted a constitution and bylaws and, two years later, the city directory recorded the meeting place of Sirh Israel Congregation as the same address as Abe Goldberg’s clothing store on West Main Street. Reverend Craft, an itinerant rabbi, conducted holiday services until members hired Samuel Cohen, an Orthodox rabbi born in Russia, who served from 1914 to 1916, when he died unexpectedly.

In 1916, the group of roughly 27 members, represented by Joel Spigel, Hyman Ougust, and Joseph Miller filed for incorporation, adopting the name B’nai Israel. Max Cohen served as president, Isaac Greenewald as treasurer, and Harry Price as secretary. That same year, Rabbi Jacob Raisin of Charleston’s Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim visited Spartanburg to “inspire a fund-raising effort.” Sunday school classes, organized by founding member Joseph Jacobs, were hosted by Mrs. I. Fuchtler in her living room until a synagogue was built in 1917 at the corner of Dean and Union Streets. The Ladies Auxiliary, led by its first president, Dr. Rosa Hirschmann Gantt, raised funds for stained glass windows and pews for a congregation that had doubled in size in just five years. The Spartanburg Herald noted that the new synagogue was open in time for High Holy Days services in 1917, and that both Reform and Orthodox traditions were practiced, at least during the holidays. Reform members observes one day under the leadership of Dr. Finklestein, with services in English, while Orthodox members celebrated both days with Dr. Isaiah Sobell, who conducted services in Hebrew.

The size of the Jewish community fluctuated during the 1920s and 1930s. Some merchants left, while a few of those who remained closed due to bankruptcy, both before and during the Great Depression. The population, estimated at 80 in 1927, nevertheless, was substantial enough to warrant a cemetery. In 1924, Rosa Gantt was instrumental in establishing a Jewish burial ground in a section of Spartanburg’s Oakwood Cemetery. Furthermore, the vitality of the congregation helped it to survive the economic hardships of the 1930s. Its 36 members reportedly maintained their rabbinical leadership throughout the Depression and, in 1937, Joseph Spigel paid off the mortgage. Spigel, who had been chairman of the building committee for the Dean Street synagogue, died that year on the same day as his good friend, Harry Price. By 1937, 98 Jews lived in Spartanburg.

David Spigel, Joseph’s younger brother, died 12 years later, leaving large bequests to Spartanburg’s Children’s Hospital and B’nai Israel. The gift to the congregation was designated for building improvements, including a new bimah and ark. His estate also provided funds to the Columbia Hebrew Benevolent Society for those needing burial assistance.

Politics and Patriotism

In 1940, shortly after being admitted to the bar, Matthew Poliakoff, a native of Blackville, South Carolina, opened a law practice in Spartanburg. His brothers, Bernard and Manning, joined him a few years later. In 1944, Matthew was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives where he served seven terms as a Democrat.

Harry Price’s sons, Bob and Bill, took over the store when their father died. Manager Wesley Morrow kept the store running smoothly while the Prices served in the military during World War II. A number of Jewish servicemen who had been stationed at Camp Croft in Spartanburg County returned to Spartanburg after the war to establish businesses. The end of World War II marked the beginning of Spartanburg’s transition from an economy based primarily on agriculture and textile manufacturing to one heavily reliant on high-tech industries. By 1947, the city’s Jewish population had reached an estimated 170, more than double the 1927 figure.

In 1940, shortly after being admitted to the bar, Matthew Poliakoff, a native of Blackville, South Carolina, opened a law practice in Spartanburg. His brothers, Bernard and Manning, joined him a few years later. In 1944, Matthew was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives where he served seven terms as a Democrat.

Harry Price’s sons, Bob and Bill, took over the store when their father died. Manager Wesley Morrow kept the store running smoothly while the Prices served in the military during World War II. A number of Jewish servicemen who had been stationed at Camp Croft in Spartanburg County returned to Spartanburg after the war to establish businesses. The end of World War II marked the beginning of Spartanburg’s transition from an economy based primarily on agriculture and textile manufacturing to one heavily reliant on high-tech industries. By 1947, the city’s Jewish population had reached an estimated 170, more than double the 1927 figure.

B'nai Israel's Sunday school in 1943

B'nai Israel's Sunday school in 1943

The Mid-Century

In 1953, B’nai Israel responded to the growth of the congregation, particularly the increasing number of children, by purchasing several acres of land on Heywood Street. The property included a house that was renovated for use as a gathering place and a Sunday school. The B’nai Israel Center, equipped by the B’nai Israel Sisterhood, was the site for social events, bar mitzvah and holiday parties. One year later, a new Jewish cemetery was founded at Spartanburg’s Greenlawn Gardens. The consecrated ground would come to be called B’nai Israel Memorial Gardens. In 1955, members hired Rabbi Max Stauber, who would serve the congregation for nearly 30 years. By this time, B’nai Israel leaned toward the Conservative tradition, although Stauber reportedly, “pleased all factions.” In 1961, the Dean Street synagogue was sold and the Torahs were carried in a procession to the B’nai Israel Center, where they were housed for two years until construction on the new temple was completed on the Heywood Street lot. In 1971, the Sunday school and Hebrew classes, which had outgrown their facilities, moved into a new education building that included a parsonage and a chapel. The education building was paid for by the congregation, with matching funds from Andrew Teszler.

In 1953, B’nai Israel responded to the growth of the congregation, particularly the increasing number of children, by purchasing several acres of land on Heywood Street. The property included a house that was renovated for use as a gathering place and a Sunday school. The B’nai Israel Center, equipped by the B’nai Israel Sisterhood, was the site for social events, bar mitzvah and holiday parties. One year later, a new Jewish cemetery was founded at Spartanburg’s Greenlawn Gardens. The consecrated ground would come to be called B’nai Israel Memorial Gardens. In 1955, members hired Rabbi Max Stauber, who would serve the congregation for nearly 30 years. By this time, B’nai Israel leaned toward the Conservative tradition, although Stauber reportedly, “pleased all factions.” In 1961, the Dean Street synagogue was sold and the Torahs were carried in a procession to the B’nai Israel Center, where they were housed for two years until construction on the new temple was completed on the Heywood Street lot. In 1971, the Sunday school and Hebrew classes, which had outgrown their facilities, moved into a new education building that included a parsonage and a chapel. The education building was paid for by the congregation, with matching funds from Andrew Teszler.

The Teszler Family

Andrew was the son of Sandor Teszler, who had arrived in the United States in 1948. Sandor owned and operated textile factories in Yugoslavia and Hungary prior to World War II. Because his skills as a textile engineer were essential to keep the factories running, he not only survived the war, he used his position to save other Jews. Emigrating after the war, Sandor established plants in the United States and ran the first racially integrated textile factory in the South, in King’s Mountain, North Carolina.

Andrew, who had studied textile engineering at North Carolina State University, was hired in 1959 by David Schwartz, owner of the Jonathan Logan Corporation, to open a plant in Spartanburg. Butte Knitting Mill became operational in January 1960, utilizing the latest innovation—double-knit technology. In his memoirs recorded for Wofford College, Sandor refers to the factory his son ran as the first vertically integrated plant in the world, generating the final product—dresses—from its own yarns. A number of Jewish families followed Andrew to the area to work at the Butte Mill which, over the next ten years, expanded significantly. In 1970, Andrew left Butte and opened his own plant, Olympia Mills. A member of Wofford College’s Board of Trustees, he built a new library on the campus, naming it in honor of his father. The Sandor Teszler Library was dedicated in 1971 and, just six weeks later, at 40 years of age, Andrew died.

Andrew was the son of Sandor Teszler, who had arrived in the United States in 1948. Sandor owned and operated textile factories in Yugoslavia and Hungary prior to World War II. Because his skills as a textile engineer were essential to keep the factories running, he not only survived the war, he used his position to save other Jews. Emigrating after the war, Sandor established plants in the United States and ran the first racially integrated textile factory in the South, in King’s Mountain, North Carolina.

Andrew, who had studied textile engineering at North Carolina State University, was hired in 1959 by David Schwartz, owner of the Jonathan Logan Corporation, to open a plant in Spartanburg. Butte Knitting Mill became operational in January 1960, utilizing the latest innovation—double-knit technology. In his memoirs recorded for Wofford College, Sandor refers to the factory his son ran as the first vertically integrated plant in the world, generating the final product—dresses—from its own yarns. A number of Jewish families followed Andrew to the area to work at the Butte Mill which, over the next ten years, expanded significantly. In 1970, Andrew left Butte and opened his own plant, Olympia Mills. A member of Wofford College’s Board of Trustees, he built a new library on the campus, naming it in honor of his father. The Sandor Teszler Library was dedicated in 1971 and, just six weeks later, at 40 years of age, Andrew died.

Jewish Businesses at the End of the 20th Century

After a long run under the proprietorship of David Greenwald’s grandsons, James and Jack Cobb, Greenewald’s finally closed its doors in 1991. Prices’ Store for Men, celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2003, and still sells men’s clothing with Harry Price, grandson of the founder, at the helm. Matthew Poliakoff died in 1979. His sons, Andrew and Gary, followed in him into law and both practice in Spartanburg. Matthew’s wife, Marsha, a renowned fiction writer, serves as Temple B’nai Israel’s historian.

After a long run under the proprietorship of David Greenwald’s grandsons, James and Jack Cobb, Greenewald’s finally closed its doors in 1991. Prices’ Store for Men, celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2003, and still sells men’s clothing with Harry Price, grandson of the founder, at the helm. Matthew Poliakoff died in 1979. His sons, Andrew and Gary, followed in him into law and both practice in Spartanburg. Matthew’s wife, Marsha, a renowned fiction writer, serves as Temple B’nai Israel’s historian.

The Jewish Community in Spartanburg Today

B'nai Israel's new synagogue

B'nai Israel's new synagogue

In 1994, B’nai Israel, home to just over 100 member families, joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, formally adopting the Reform tradition. The region’s ongoing economic strength in the high-tech sector continues to attract newcomers to the area. By 2001, an estimated 500 Jews lived in the city. Spartanburg’s Jewish community has grown tremendously just since the turn of the 21st century and the temple has expanded to accommodate the influx of professionals and businessmen and women. Spartanburg's Jewish community has an esteemed history, and a bright future.