Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Austin, Texas

Austin: Historical Overview

|

Few Jewish communities in the United States have been transformed over the past few decades the way Austin, Texas has. For over a century, Austin had been home to a small Jewish community that was often overshadowed by places like Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, and even Waco.

Originally named Waterloo, the small village on the banks of the Colorado River was selected to be the capital of the Texas Republic in 1839 and was renamed to honor the father of Anglo settlement in Texas, Stephen F. Austin. It was a relatively sleepy capital city, known more for its laid back atmosphere than as a bustling center for commerce. Since the 1980s, this has changed, as Austin has emerged as a center for high tech industry. As Austin has grown, so has its Jewish population. Since 1968, Austin’s Jewish population has increased by over twenty-fold, becoming one of the fastest growing Jewish communities in the country. By the 21st century, Austin had become a diverse and vibrant center for Jewish life in the Southern sunbelt. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Austin

Early Settlers

The first Jewish resident, Phineas DeCordova, became one of its most influential. The half-brother of land agent Jacob DeCordova, Phineas came to Galveston from Jamaica in 1848. He joined Jacob in a land business, working to attract European immigrants to Texas through their publishing of the Texas Herald and Immigrant Guide. Phineas DeCordova moved to Austin in 1849 after Governor Peter Bell invited him to work with the state government to attract immigrants to Texas. DeCordova opened a land company with partner James McKinney. He later befriended Governor Elisha Pease, managing his estate and land holdings. DeCordova was a politically active Democrat, serving as a city alderman in 1857 and on the Texas State Democratic Executive Committee. DeCordova supported the Confederate cause, serving as both a state senator and as secretary of the Texas Military Board during the war. After the war, DeCordova, served as a U.S. Commissioner for the Western District of Texas, while also becoming Grand Master of the Odd Fellows of Texas, the first Jew to hold such a position in the United States.

Only a handful of Jews lived in Austin before the Civil War. Soon after the war, a growing number of Jewish immigrants settled in the small central Texas town. B. Melasky left Poland in 1856, settling in Texas by 1859. After time in New Braunfels and San Marcos, Melasky enlisted in the Confederate cause at the start of the war. After the South’s defeat, Melasky moved to Austin, where he opened a clothing store on Congress Avenue with Abraham Biberstein. Later known as Melasky & Son, the store was a quick success; by 1870, Melasky owned $10,000 worth of personal estate. Perhaps the most prominent Jewish businessman in Austin during this period was Henry Hirschfeld. Born in Posen in 1834, Hirschfeld settled in Texas in 1850. After fighting for the South during the Civil War, he moved to Austin and opened the Capitol Clothing House in 1866. He married Jennie Melasky in 1868. After enjoying economic success with his store, he sold it in 1886 to focus his time on real estate and investments. Hirshfeld was one of the founders of the Austin National Bank in 1890, and served on its board until his death in 1911. He was also a charter member of Austin’s first Masonic Lodge. During the Reconstruction era, about 15 Jewish families lived in Austin; most were German immigrants who owned retail business.

The first Jewish resident, Phineas DeCordova, became one of its most influential. The half-brother of land agent Jacob DeCordova, Phineas came to Galveston from Jamaica in 1848. He joined Jacob in a land business, working to attract European immigrants to Texas through their publishing of the Texas Herald and Immigrant Guide. Phineas DeCordova moved to Austin in 1849 after Governor Peter Bell invited him to work with the state government to attract immigrants to Texas. DeCordova opened a land company with partner James McKinney. He later befriended Governor Elisha Pease, managing his estate and land holdings. DeCordova was a politically active Democrat, serving as a city alderman in 1857 and on the Texas State Democratic Executive Committee. DeCordova supported the Confederate cause, serving as both a state senator and as secretary of the Texas Military Board during the war. After the war, DeCordova, served as a U.S. Commissioner for the Western District of Texas, while also becoming Grand Master of the Odd Fellows of Texas, the first Jew to hold such a position in the United States.

Only a handful of Jews lived in Austin before the Civil War. Soon after the war, a growing number of Jewish immigrants settled in the small central Texas town. B. Melasky left Poland in 1856, settling in Texas by 1859. After time in New Braunfels and San Marcos, Melasky enlisted in the Confederate cause at the start of the war. After the South’s defeat, Melasky moved to Austin, where he opened a clothing store on Congress Avenue with Abraham Biberstein. Later known as Melasky & Son, the store was a quick success; by 1870, Melasky owned $10,000 worth of personal estate. Perhaps the most prominent Jewish businessman in Austin during this period was Henry Hirschfeld. Born in Posen in 1834, Hirschfeld settled in Texas in 1850. After fighting for the South during the Civil War, he moved to Austin and opened the Capitol Clothing House in 1866. He married Jennie Melasky in 1868. After enjoying economic success with his store, he sold it in 1886 to focus his time on real estate and investments. Hirshfeld was one of the founders of the Austin National Bank in 1890, and served on its board until his death in 1911. He was also a charter member of Austin’s first Masonic Lodge. During the Reconstruction era, about 15 Jewish families lived in Austin; most were German immigrants who owned retail business.

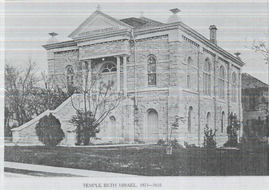

Beth Israel's first synagogue

Beth Israel's first synagogue

Early Organized Jewish Life in Austin

Austin’s small number of Jews began to organize very early, though it took them several attempts to create a successful congregation. In 1866, local Jews bought land for a cemetery. Six years later, they organized the Hebrew Benevolent Association, with B. Melasky as its president. The group tried to raise money for a synagogue, but was unsuccessful, prompting them to disband. In 1874, Rev. J.M. Chumaceiro of Charleston, South Carolina, visited Austin to try to organize a B’nai B’rith chapter. Austin Jews decided that a religious congregation was a higher priority and created B’nai Sholom congregation with Henry Hirschfeld as its president. Though the congregation quickly collected over $1300 in pledges toward a synagogue, the group had disbanded by the end of 1875. The effort to establish B’nai B’rith was more successful. In 1875, 20 men created an Austin lodge of the national Jewish fraternal society, with Henry Hirschfeld serving as its first president.

In September of 1876, Austin Jews tried once again to establish a lasting congregation. This time the effort was encouraged by the local newspaper, which noted that several other Texas cities had Jewish congregations, and “we can see no reason why Austin should not keep company with them.” The same day as the newspaper’s endorsement, 30 Jews gathered at the Odd Fellows Hall and established Beth Israel, Austin’s first lasting Jewish congregation. The two most prominent Jews in town, Henry Hirschfeld and Phineas DeCordova, were its first president and vice president, respectively. B. Melsaky lent his Torah to the congregation. The group quickly raised $2500 to build a synagogue. One of their first debates was whether to solicit non-Jews for the synagogue fund; the group voted narrowly to restrict their fundraising to the Jewish community. They bought land for a synagogue in 1877, but had a hard time raising money for the building.

That same year, they hired a Dr. Gluck to lead the High Holiday services held at the Odd Fellows Hall; he remained in Austin for three additional months. During his short tenure, Gluck started a Sunday school, which was run by Sigmund Philipson. Gluck returned in the spring of 1878, and led the congregation’s first confirmation ceremony. Gluck formally invited Austin’s mayor and aldermen to attend the ceremony in an effort to show these leaders that Jewish worship was not strange or foreign. B’nai B’rith leader Charles Wessolowsky visited Austin in 1879, and found 35 Jewish families living in the city, most of whom were thriving economically. He regretted that Austin Jews had not yet built a synagogue, and encouraged them to do so.

Despite this activity, by 1881, the group had become inactive, and it looked like Beth Israel might meet the same fate as earlier efforts to organize congregations in Austin. The following year, Rev. Chumaceiro returned to Austin and inspired the group to revitalize the congregation and move forward with the building campaign. After his entreaties, the members decided to reopen the religious school, hire a rabbi for the High Holidays, and begin a new push to raise money for a synagogue. They held Purim Balls to raise funds while members who traveled north for business solicited contributions from wholesale suppliers and Jewish organizations there. They even asked non-Jews for donations, receiving $640 from them. Finally, in 1884, Beth Israel dedicated its first synagogue at 11th and San Jacinto Streets. The Hebrew Ladies Aid Society donated $120 to buy an ark for the new building. For its first year, the temple did not have permanent seats; they did not purchase pews for the sanctuary until 1885. In 1892, women established the Ladies Auxiliary Society, which later became the temple Sisterhood.

Beth Israel had brought down a rabbinic student from Hebrew Union College in 1883 and 1884, and used Isaac Mayer Wise’s Reform Minhag America prayer book. Although members still wore yarmulkes, their practice was largely Reform. In 1885, the congregation advertised for a rabbi in the American Israelite newspaper, calling for “an American Hebrew minister who can deliver English sermons,” run the Sunday school, and direct the choir. Rabbi A.R. Levy answered this ad, but only spent a year at Beth Israel. He returned five years later and stayed for nine years. Although Beth Israel was Reform, it did not join the Union of American Hebrew Congregations until 1907. That year, Beth Israel had 51 members and 35 students in its Sunday school. Rabbi David Rosenbaum came to Beth Israel in 1911 and convinced the congregation to adopt the new Reform Union Prayer Book, although he continued to wear a yarmulke to keep more traditional members happy.

Austin’s small number of Jews began to organize very early, though it took them several attempts to create a successful congregation. In 1866, local Jews bought land for a cemetery. Six years later, they organized the Hebrew Benevolent Association, with B. Melasky as its president. The group tried to raise money for a synagogue, but was unsuccessful, prompting them to disband. In 1874, Rev. J.M. Chumaceiro of Charleston, South Carolina, visited Austin to try to organize a B’nai B’rith chapter. Austin Jews decided that a religious congregation was a higher priority and created B’nai Sholom congregation with Henry Hirschfeld as its president. Though the congregation quickly collected over $1300 in pledges toward a synagogue, the group had disbanded by the end of 1875. The effort to establish B’nai B’rith was more successful. In 1875, 20 men created an Austin lodge of the national Jewish fraternal society, with Henry Hirschfeld serving as its first president.

In September of 1876, Austin Jews tried once again to establish a lasting congregation. This time the effort was encouraged by the local newspaper, which noted that several other Texas cities had Jewish congregations, and “we can see no reason why Austin should not keep company with them.” The same day as the newspaper’s endorsement, 30 Jews gathered at the Odd Fellows Hall and established Beth Israel, Austin’s first lasting Jewish congregation. The two most prominent Jews in town, Henry Hirschfeld and Phineas DeCordova, were its first president and vice president, respectively. B. Melsaky lent his Torah to the congregation. The group quickly raised $2500 to build a synagogue. One of their first debates was whether to solicit non-Jews for the synagogue fund; the group voted narrowly to restrict their fundraising to the Jewish community. They bought land for a synagogue in 1877, but had a hard time raising money for the building.

That same year, they hired a Dr. Gluck to lead the High Holiday services held at the Odd Fellows Hall; he remained in Austin for three additional months. During his short tenure, Gluck started a Sunday school, which was run by Sigmund Philipson. Gluck returned in the spring of 1878, and led the congregation’s first confirmation ceremony. Gluck formally invited Austin’s mayor and aldermen to attend the ceremony in an effort to show these leaders that Jewish worship was not strange or foreign. B’nai B’rith leader Charles Wessolowsky visited Austin in 1879, and found 35 Jewish families living in the city, most of whom were thriving economically. He regretted that Austin Jews had not yet built a synagogue, and encouraged them to do so.

Despite this activity, by 1881, the group had become inactive, and it looked like Beth Israel might meet the same fate as earlier efforts to organize congregations in Austin. The following year, Rev. Chumaceiro returned to Austin and inspired the group to revitalize the congregation and move forward with the building campaign. After his entreaties, the members decided to reopen the religious school, hire a rabbi for the High Holidays, and begin a new push to raise money for a synagogue. They held Purim Balls to raise funds while members who traveled north for business solicited contributions from wholesale suppliers and Jewish organizations there. They even asked non-Jews for donations, receiving $640 from them. Finally, in 1884, Beth Israel dedicated its first synagogue at 11th and San Jacinto Streets. The Hebrew Ladies Aid Society donated $120 to buy an ark for the new building. For its first year, the temple did not have permanent seats; they did not purchase pews for the sanctuary until 1885. In 1892, women established the Ladies Auxiliary Society, which later became the temple Sisterhood.

Beth Israel had brought down a rabbinic student from Hebrew Union College in 1883 and 1884, and used Isaac Mayer Wise’s Reform Minhag America prayer book. Although members still wore yarmulkes, their practice was largely Reform. In 1885, the congregation advertised for a rabbi in the American Israelite newspaper, calling for “an American Hebrew minister who can deliver English sermons,” run the Sunday school, and direct the choir. Rabbi A.R. Levy answered this ad, but only spent a year at Beth Israel. He returned five years later and stayed for nine years. Although Beth Israel was Reform, it did not join the Union of American Hebrew Congregations until 1907. That year, Beth Israel had 51 members and 35 students in its Sunday school. Rabbi David Rosenbaum came to Beth Israel in 1911 and convinced the congregation to adopt the new Reform Union Prayer Book, although he continued to wear a yarmulke to keep more traditional members happy.

Joe Koen & Son Jewelers.

Joe Koen & Son Jewelers. Photo courtesy of Brad Koen

A Growing Community

By 1890, there were an estimated 26 Jewish-owned businesses in Austin. Eleven of these were either dry goods, clothing, or general stores, while four were grocery stores. Another four were saloons or liquor businesses. Austin Jews owned a wide array of other enterprises, selling cigars, books, jewelry, junk, and crockery. Often these businesses were partnerships. Morris Bernhaim and Joseph Jacobs owned a dry goods store together, while Simon Goldstein and Sigmund Philipson owned a cigar business.

One of the most prominent and lasting Jewish-owned businesses is Joe Koen & Son Jewelers. Joe Koen left Russia for New York in 1883. He originally planned to settle in San Antonio and ply his trade as a watchmaker. On his way to the Alamo city, he stopped in Austin, and liked it so much that he decided to open his business there. In 1883, Koen opened a jewelry and watch repair shop in Austin; in 1888, he moved the business to East 6th Street. Koen’s son William joined the business in 1918. Today, the fourth generation of the Koen family still runs Joe Koen & Son Jewelers. Joe Koen was a longtime leader of the Austin Jewish community, serving as president of Beth Israel from 1899 until 1944. His son was president of the Reform congregation from 1946 to 1948. Joe’s granddaughter, Carolyn Koen Turner, became the first female president of Beth Israel in 1984.

Joe Koen represented the beginning of a wave of Russian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants who would settle in Austin in the late 19th and early 20th century. Austin’s Jewish population grew from about 200 people in 1907 to 575 in 1937, largely due to this wave. Leopold Cohen left Russia in 1894, settling in Galveston initially. After the Hurricane of 1900, he moved to Austin, where he was joined by his older brother Israel. Both became dry goods merchants and active leaders of Austin’s Orthodox community. Another set of brothers, Louis and Jim Novy, came from Poland through the port of Galveston. Louis lived in Dallas, Ennis, and Temple before moving to Austin by 1917. He managed the Hancock Opera House, later changing its name to the Capitol Theater. He brought over his younger brother Jim, who joined him in Austin. Jim Novy started a scrap metal business before branching out into several different enterprises. In the 1930s, Jim Novy befriended a young local politician named Lyndon Johnson, establishing a relationship that would later provide big dividends for Austin’s small Jewish community. Most of these Eastern European immigrants opened small retail stores, following the pattern set by the earlier German immigrants.

By 1890, there were an estimated 26 Jewish-owned businesses in Austin. Eleven of these were either dry goods, clothing, or general stores, while four were grocery stores. Another four were saloons or liquor businesses. Austin Jews owned a wide array of other enterprises, selling cigars, books, jewelry, junk, and crockery. Often these businesses were partnerships. Morris Bernhaim and Joseph Jacobs owned a dry goods store together, while Simon Goldstein and Sigmund Philipson owned a cigar business.

One of the most prominent and lasting Jewish-owned businesses is Joe Koen & Son Jewelers. Joe Koen left Russia for New York in 1883. He originally planned to settle in San Antonio and ply his trade as a watchmaker. On his way to the Alamo city, he stopped in Austin, and liked it so much that he decided to open his business there. In 1883, Koen opened a jewelry and watch repair shop in Austin; in 1888, he moved the business to East 6th Street. Koen’s son William joined the business in 1918. Today, the fourth generation of the Koen family still runs Joe Koen & Son Jewelers. Joe Koen was a longtime leader of the Austin Jewish community, serving as president of Beth Israel from 1899 until 1944. His son was president of the Reform congregation from 1946 to 1948. Joe’s granddaughter, Carolyn Koen Turner, became the first female president of Beth Israel in 1984.

Joe Koen represented the beginning of a wave of Russian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants who would settle in Austin in the late 19th and early 20th century. Austin’s Jewish population grew from about 200 people in 1907 to 575 in 1937, largely due to this wave. Leopold Cohen left Russia in 1894, settling in Galveston initially. After the Hurricane of 1900, he moved to Austin, where he was joined by his older brother Israel. Both became dry goods merchants and active leaders of Austin’s Orthodox community. Another set of brothers, Louis and Jim Novy, came from Poland through the port of Galveston. Louis lived in Dallas, Ennis, and Temple before moving to Austin by 1917. He managed the Hancock Opera House, later changing its name to the Capitol Theater. He brought over his younger brother Jim, who joined him in Austin. Jim Novy started a scrap metal business before branching out into several different enterprises. In the 1930s, Jim Novy befriended a young local politician named Lyndon Johnson, establishing a relationship that would later provide big dividends for Austin’s small Jewish community. Most of these Eastern European immigrants opened small retail stores, following the pattern set by the earlier German immigrants.

Initially, these more-traditional minded immigrants were part of the Reform congregation Beth Israel. In 1901, they began to hold separate Orthodox services for the High Holidays, meeting at the Knights of Pythias Hall for services led by Rabbi Ben Nathanson of San Antonio. Later, they started to hold daily minyans at people’s stores and homes. Despite this, the small Orthodox group still worshiped at Beth Israel for Shabbat. By 1914, their numbers had grown large enough to support a second congregation. Naming themselves Agudas Achim (Society of Brothers), the group met at the home of Ike Frank for the High Holidays that year. For the next several years, they met in various rented halls for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Once, they even met on the floor of the Texas Senate; Beth Israel president Joe Koen helped arrange this for them. Orthodox Jews from surrounding towns would travel to Austin for the holidays to worship with Agudas Achim, which had 25 members by 1921.

In 1924, Agudas Achim was formally chartered and the group purchased a small house at 7th and San Jacinto Streets, which they converted into a synagogue. Israel Cohen was the first president of Agudas Achim, serving from 1924 until his death in 1936. In 1929, they hired Bernard Tanenbaum to be their chazzan (cantor) and Hebrew teacher. While the children of the congregation learned Hebrew from Tanenbaum on weekday afternoons, they went to Sunday school at Beth Israel. It was extremely unusual for a Reform and Orthodox congregation to hold a joint Sunday school; this arrangement reflected the small size and limited resources of these congregations as well as the friendly relations between them.

The small house used by the congregation was inadequate, and members soon began to look for a new site. In 1930, they bought land at 10th and San Jacinto streets, just one block from Beth Israel. Agudas Achim dedicated its new synagogue the following year. Jim Novy headed the building committee and traveled around Texas and surrounding states raising money for the building fund. In the 1930s, the congregation hired its first ordained rabbi, Harold Katz. Agudas Achim was still an Orthodox congregation then. Their new synagogue contained a mikvah, though it was rarely used. Most members kept kosher and walked to synagogue on Shabbat.

Although they shared a Sunday school, there were social and class divisions between the Reform members of Beth Israel and the Orthodox immigrants of Agudas Achim. There was not much social interaction between these two segments of the Austin Jewish community. While both groups were predominately merchants, Beth Israel members tended to own higher-end stores on Congress Avenue, while Agudas members tended to own smaller businesses on East Sixth Street. Of course, Jews of both congregations lived among non-Jews; there was never a predominantly Jewish enclave in the city. The Jewish children raised in Austin had lots of non-Jewish friends. Austin Jews suffered little explicit anti-Semitism.

In 1924, Agudas Achim was formally chartered and the group purchased a small house at 7th and San Jacinto Streets, which they converted into a synagogue. Israel Cohen was the first president of Agudas Achim, serving from 1924 until his death in 1936. In 1929, they hired Bernard Tanenbaum to be their chazzan (cantor) and Hebrew teacher. While the children of the congregation learned Hebrew from Tanenbaum on weekday afternoons, they went to Sunday school at Beth Israel. It was extremely unusual for a Reform and Orthodox congregation to hold a joint Sunday school; this arrangement reflected the small size and limited resources of these congregations as well as the friendly relations between them.

The small house used by the congregation was inadequate, and members soon began to look for a new site. In 1930, they bought land at 10th and San Jacinto streets, just one block from Beth Israel. Agudas Achim dedicated its new synagogue the following year. Jim Novy headed the building committee and traveled around Texas and surrounding states raising money for the building fund. In the 1930s, the congregation hired its first ordained rabbi, Harold Katz. Agudas Achim was still an Orthodox congregation then. Their new synagogue contained a mikvah, though it was rarely used. Most members kept kosher and walked to synagogue on Shabbat.

Although they shared a Sunday school, there were social and class divisions between the Reform members of Beth Israel and the Orthodox immigrants of Agudas Achim. There was not much social interaction between these two segments of the Austin Jewish community. While both groups were predominately merchants, Beth Israel members tended to own higher-end stores on Congress Avenue, while Agudas members tended to own smaller businesses on East Sixth Street. Of course, Jews of both congregations lived among non-Jews; there was never a predominantly Jewish enclave in the city. The Jewish children raised in Austin had lots of non-Jewish friends. Austin Jews suffered little explicit anti-Semitism.

Topfer Center for Jewish Life at UT

Topfer Center for Jewish Life at UT

University of Texas

Austin is home to the state’s major public university, the University of Texas, which has had a profound impact on the local Jewish community since the early 20th century, when a handful of Jewish faculty worked at the school. Dr. Hyman Ettlinger, a Harvard-trained mathematician, came to UT in 1913. Ettlinger went on to write a popular calculus textbook and chair the school’s math department for 25 years. Ettlinger was very active in Austin Jewish life. Ettlinger taught Sunday school at Beth Israel for many years, and served as secretary of the congregation from 1927 to 1945. When Beth Israel did not have a rabbi for a year in the 1920s, Ettlinger led services each week. During the early 20th century, there were a small number of other Jewish faculty members at UT, most of whom were involved in the Austin Jewish community. After World War II, the number of Jewish faculty grew significantly. Harry Leon chaired the Classics Department from 1947 to 1967, and published widely in the field. He taught the first Hebrew class at UT. His wife Ernestine Leon also taught in the Classics Department.

Ettlinger helped form the UT Menorah Society soon after he arrived in 1913, when there were only 30 Jewish students at the university. By 1917, this number had grown to 66, representing 2.7% of the overall student body. The Menorah Society was succeeded by Hillel in 1929, which constructed its first building near campus the following year. Initially, UT Hillel was closely tied with Beth Israel, with the congregation’s spiritual leader also serving as Hillel rabbi. By 1945, Hillel had grown large enough that it was able to support its own rabbi and director. The Jewish population of UT grew steadily over the 20th century. Many of the Jews raised in Austin went to the hometown school. By 1927, UT had three Jewish fraternities and one sorority. The number of these organizations increased in the 1930s, along with the number of Jewish students. By 1933, 325 Jewish students attended the university.

Austin is home to the state’s major public university, the University of Texas, which has had a profound impact on the local Jewish community since the early 20th century, when a handful of Jewish faculty worked at the school. Dr. Hyman Ettlinger, a Harvard-trained mathematician, came to UT in 1913. Ettlinger went on to write a popular calculus textbook and chair the school’s math department for 25 years. Ettlinger was very active in Austin Jewish life. Ettlinger taught Sunday school at Beth Israel for many years, and served as secretary of the congregation from 1927 to 1945. When Beth Israel did not have a rabbi for a year in the 1920s, Ettlinger led services each week. During the early 20th century, there were a small number of other Jewish faculty members at UT, most of whom were involved in the Austin Jewish community. After World War II, the number of Jewish faculty grew significantly. Harry Leon chaired the Classics Department from 1947 to 1967, and published widely in the field. He taught the first Hebrew class at UT. His wife Ernestine Leon also taught in the Classics Department.

Ettlinger helped form the UT Menorah Society soon after he arrived in 1913, when there were only 30 Jewish students at the university. By 1917, this number had grown to 66, representing 2.7% of the overall student body. The Menorah Society was succeeded by Hillel in 1929, which constructed its first building near campus the following year. Initially, UT Hillel was closely tied with Beth Israel, with the congregation’s spiritual leader also serving as Hillel rabbi. By 1945, Hillel had grown large enough that it was able to support its own rabbi and director. The Jewish population of UT grew steadily over the 20th century. Many of the Jews raised in Austin went to the hometown school. By 1927, UT had three Jewish fraternities and one sorority. The number of these organizations increased in the 1930s, along with the number of Jewish students. By 1933, 325 Jewish students attended the university.

Jewish Organizations in Austin

College fraternities and Hillel were not the only non-religious Jewish organizations in Austin. In 1906, Austin Jews established the Harmony Club, a short-lived social club that never had a permanent building. Local Zionists founded the Workers of Zion in the early 1900s. Lydia Littman was the longtime leader of the organization, which was affiliated with the national Federation of American Zionists. In 1907, Austin Jews, led by Joe Koen and Moses Davis, established the Hebrew Benevolent Society to help poor Jewish immigrants. In 1924, the society was folded into the new Federation of Jewish Charities, which consolidated all of the Jewish charitable giving in the city. Later, it became known as the Austin Jewish Federation. The Ladies Guild, which focused on charity work, was founded in 1915; four years later it affiliated with the national Council of Jewish Women.

College fraternities and Hillel were not the only non-religious Jewish organizations in Austin. In 1906, Austin Jews established the Harmony Club, a short-lived social club that never had a permanent building. Local Zionists founded the Workers of Zion in the early 1900s. Lydia Littman was the longtime leader of the organization, which was affiliated with the national Federation of American Zionists. In 1907, Austin Jews, led by Joe Koen and Moses Davis, established the Hebrew Benevolent Society to help poor Jewish immigrants. In 1924, the society was folded into the new Federation of Jewish Charities, which consolidated all of the Jewish charitable giving in the city. Later, it became known as the Austin Jewish Federation. The Ladies Guild, which focused on charity work, was founded in 1915; four years later it affiliated with the national Council of Jewish Women.

Jim Novy introducing President Johnson

Jim Novy introducing President Johnson at the synagogue dedication.

World War II and the Post-War Era

Austin Jews were actively involved in World War II. While a number served in the armed forces, those on the homefront offered hospitality to Jewish servicemen stationed in the area. Both of Austin’s congregations lent Torahs to Bergstrom Air Base in Austin and Fort Hood in Killeen. They also hosted Jewish soldiers at special programs sponsored by the Jewish Welfare Board. Although documentary evidence is sketchy, it is generally believed that Jim Novy used his close relationship with Congressman Lyndon Johnson to rescue 40 Jews from Europe in the late 1930s. Johnson got visas for these refugees and found them jobs with the National Youth Administration in Texas. Reportedly, Novy used funds from the Joint Distribution Committee to reimburse the NYA. Many of these refugees ended up settling in Austin.

After World War II, the Austin Jewish community enjoyed a period of sustained growth. Beth Israel grew from 80 families in 1945 to 203 by 1962. It added new religious school rooms in 1947 to handle this baby boom. Rabbis tended not to stay very long at Beth Israel, although some made a significant impact on the larger community. Bertram Klausner became Beth Israel’s rabbi in 1947; during his 7-year tenure, he was active in interfaith work, serving as president of the Austin Ministerial Alliance in 1949. During his tenure, the Reform congregation began to reintroduce some traditional elements, including the bar mitzvah as well as the new bat mitzvah ritual for girls.

Around the same time, Agudas Achim moved away from Orthodoxy. Rabbi Joel Dekoven, who was hired in 1946, introduced a more Conservative style of services, including English readings. In 1948, Agudas Achim officially joined the Conservative movement and hired a rabbi ordained by the Jewish Theological Seminary, Benson Skoff. These changes reflected an effort to appeal to native-born second generation members who no longer wished to follow Orthodoxy’s strict practices. With these adaptations, Agudas Achim grew, reaching 137 member families by the end of the 1940s. In 1947, the congregation was large enough to support its own Sunday school, so they broke away from the joint school they had shared with Beth Israel since the 1920s. Within the Conservative Movement, Agudas Achim embraced gender equality fairly early. Naomi Worob became the first women to serve on the board in 1970; in 1976, Marilyn Stahl became its first female president. By the 1980s, women were allowed to read Torah and receive aliyot.

By the 1950s, both congregations had begun to discuss moving out of downtown Austin to the growing northern suburbs of the city, where most of its members were now living. With its post-war boom, Beth Israel outgrew its building. Even its new classrooms couldn’t hold the 100 children in its religious school in 1953. They began to use a nearby bank building and Elk’s Lodge for classroom space on Sundays. In 1957, they dedicated a new, larger temple on Seiders Avenue; Governor Price Daniel and Mayor Tom Miller spoke during the dedication ceremony. The new building did not include a sanctuary initially, as their highest priority was a large education and administration wing. Services were held in a small chapel or in the auditorium until the new sanctuary was finally completed in 1967. The Beth Israel Sisterhood played a key role in raising the money for the new sanctuary, holding popular annual themed parties like “Evening in the Orient” and “Evening in Paris.” Helen Smith chaired the sanctuary building committee. In 1962, Beth Israel hired Louis Firestein, who became the longest-serving rabbi in the congregation’s history, staying until 1987.

Agudas Achim, though smaller than Beth Israel, had also outgrown its building. They bought land on Bull Creek Road in 1958 for $19,500. Their fundraising effort to build on the new land got a big boost in 1962 when they sold their old property to the U.S. Government for $144,000; the government tore down the synagogue and constructed a new federal building on the property. With this windfall, possibly the result of Jim Novy’s influence with Vice President Lyndon Johnson, the congregation was able to begin construction on a new synagogue. Jim Novy, who had headed up the fundraising effort for the new building, as he had done for the old building three decades earlier, got his old friend Lyndon Johnson to agree to give the keynote address at the new synagogue’s dedication, which was set for November 24, 1963. When history interceded in Dallas on November 22nd with the assassination of President Kennedy, the ceremony was postponed. A month later, now President Lyndon Johnson came to Austin and dedicated the new synagogue due to his friendship with Novy, who introduced the president that night. This marked the first and only time a U.S. President has dedicated a Jewish house of worship.

Novy used his influence with LBJ to assist various Jewish causes. He lobbied LBJ when he was in the Senate and the White House to support aid for Israel. Johnson selected Novy to deliver a special message from the president to the 26th World Zionist Congress in Jerusalem in 1964. Novy also convinced President Johnson to set aside $2 million in aid to Israel to fund the Encyclopedia Judaica project. For his assistance, Novy was named an honorary vice president of the project, and received a brief entry in the 16-volume encyclopedia, published in Jerusalem in 1971. Agudas Achim received 500 free sets of the encyclopedia, which it sold, using the proceeds to pay off their mortgage on the new building.

Austin Jews were actively involved in World War II. While a number served in the armed forces, those on the homefront offered hospitality to Jewish servicemen stationed in the area. Both of Austin’s congregations lent Torahs to Bergstrom Air Base in Austin and Fort Hood in Killeen. They also hosted Jewish soldiers at special programs sponsored by the Jewish Welfare Board. Although documentary evidence is sketchy, it is generally believed that Jim Novy used his close relationship with Congressman Lyndon Johnson to rescue 40 Jews from Europe in the late 1930s. Johnson got visas for these refugees and found them jobs with the National Youth Administration in Texas. Reportedly, Novy used funds from the Joint Distribution Committee to reimburse the NYA. Many of these refugees ended up settling in Austin.

After World War II, the Austin Jewish community enjoyed a period of sustained growth. Beth Israel grew from 80 families in 1945 to 203 by 1962. It added new religious school rooms in 1947 to handle this baby boom. Rabbis tended not to stay very long at Beth Israel, although some made a significant impact on the larger community. Bertram Klausner became Beth Israel’s rabbi in 1947; during his 7-year tenure, he was active in interfaith work, serving as president of the Austin Ministerial Alliance in 1949. During his tenure, the Reform congregation began to reintroduce some traditional elements, including the bar mitzvah as well as the new bat mitzvah ritual for girls.

Around the same time, Agudas Achim moved away from Orthodoxy. Rabbi Joel Dekoven, who was hired in 1946, introduced a more Conservative style of services, including English readings. In 1948, Agudas Achim officially joined the Conservative movement and hired a rabbi ordained by the Jewish Theological Seminary, Benson Skoff. These changes reflected an effort to appeal to native-born second generation members who no longer wished to follow Orthodoxy’s strict practices. With these adaptations, Agudas Achim grew, reaching 137 member families by the end of the 1940s. In 1947, the congregation was large enough to support its own Sunday school, so they broke away from the joint school they had shared with Beth Israel since the 1920s. Within the Conservative Movement, Agudas Achim embraced gender equality fairly early. Naomi Worob became the first women to serve on the board in 1970; in 1976, Marilyn Stahl became its first female president. By the 1980s, women were allowed to read Torah and receive aliyot.

By the 1950s, both congregations had begun to discuss moving out of downtown Austin to the growing northern suburbs of the city, where most of its members were now living. With its post-war boom, Beth Israel outgrew its building. Even its new classrooms couldn’t hold the 100 children in its religious school in 1953. They began to use a nearby bank building and Elk’s Lodge for classroom space on Sundays. In 1957, they dedicated a new, larger temple on Seiders Avenue; Governor Price Daniel and Mayor Tom Miller spoke during the dedication ceremony. The new building did not include a sanctuary initially, as their highest priority was a large education and administration wing. Services were held in a small chapel or in the auditorium until the new sanctuary was finally completed in 1967. The Beth Israel Sisterhood played a key role in raising the money for the new sanctuary, holding popular annual themed parties like “Evening in the Orient” and “Evening in Paris.” Helen Smith chaired the sanctuary building committee. In 1962, Beth Israel hired Louis Firestein, who became the longest-serving rabbi in the congregation’s history, staying until 1987.

Agudas Achim, though smaller than Beth Israel, had also outgrown its building. They bought land on Bull Creek Road in 1958 for $19,500. Their fundraising effort to build on the new land got a big boost in 1962 when they sold their old property to the U.S. Government for $144,000; the government tore down the synagogue and constructed a new federal building on the property. With this windfall, possibly the result of Jim Novy’s influence with Vice President Lyndon Johnson, the congregation was able to begin construction on a new synagogue. Jim Novy, who had headed up the fundraising effort for the new building, as he had done for the old building three decades earlier, got his old friend Lyndon Johnson to agree to give the keynote address at the new synagogue’s dedication, which was set for November 24, 1963. When history interceded in Dallas on November 22nd with the assassination of President Kennedy, the ceremony was postponed. A month later, now President Lyndon Johnson came to Austin and dedicated the new synagogue due to his friendship with Novy, who introduced the president that night. This marked the first and only time a U.S. President has dedicated a Jewish house of worship.

Novy used his influence with LBJ to assist various Jewish causes. He lobbied LBJ when he was in the Senate and the White House to support aid for Israel. Johnson selected Novy to deliver a special message from the president to the 26th World Zionist Congress in Jerusalem in 1964. Novy also convinced President Johnson to set aside $2 million in aid to Israel to fund the Encyclopedia Judaica project. For his assistance, Novy was named an honorary vice president of the project, and received a brief entry in the 16-volume encyclopedia, published in Jerusalem in 1971. Agudas Achim received 500 free sets of the encyclopedia, which it sold, using the proceeds to pay off their mortgage on the new building.

|

AUDIO: Jim Novy introducing President Johnson.

|

Mid-Century Jewish Businesses

As late as the 1960s, Jews still owned several of the downtown stores on Congress Avenue. They owned many of the city’s clothing and jewelry businesses. Jewish-owned stores included Snyder’s, Slax, Jack Morton’s, Goodfriends; Yaring’s, Benolds, Kara-vel, Central Auto Supply, and Joe Koen & Son. Some Austin Jews were involved in manufacturing. Harry Smith started Economy Furniture in the early 20th century; his sons Milton, Phil, and Elmer soon joined the furniture manufacturing company. By the 1940s, Phil and Elmer had moved to Waco, and Milton and his wife Helen ran the business. By 1964, Economy Furniture had a 600,000 square foot factory in Austin. Milton was a leading figure in the Austin business community, serving many years on the board of Capital National Bank. He also helped to organize and served as chairman of the Dallas Furniture Mart, a leading showcase for furniture manufacturers. Both Helen and Milton Smith were among the founders of the Community Relations Council of Austin in the early 1950s; they also both served on the boards of the local symphony and Aqua Festival. The Smiths were also important leaders of the Jewish community. Beth Israel named the auditorium of its new building after Helen and Milton Smith in 1967. Helen served as international president of B’nai B’rith Women from 1974 to 1976, while Milton served as head of the Austin Jewish Federation and the Texas Jewish Historical Society

As late as the 1960s, Jews still owned several of the downtown stores on Congress Avenue. They owned many of the city’s clothing and jewelry businesses. Jewish-owned stores included Snyder’s, Slax, Jack Morton’s, Goodfriends; Yaring’s, Benolds, Kara-vel, Central Auto Supply, and Joe Koen & Son. Some Austin Jews were involved in manufacturing. Harry Smith started Economy Furniture in the early 20th century; his sons Milton, Phil, and Elmer soon joined the furniture manufacturing company. By the 1940s, Phil and Elmer had moved to Waco, and Milton and his wife Helen ran the business. By 1964, Economy Furniture had a 600,000 square foot factory in Austin. Milton was a leading figure in the Austin business community, serving many years on the board of Capital National Bank. He also helped to organize and served as chairman of the Dallas Furniture Mart, a leading showcase for furniture manufacturers. Both Helen and Milton Smith were among the founders of the Community Relations Council of Austin in the early 1950s; they also both served on the boards of the local symphony and Aqua Festival. The Smiths were also important leaders of the Jewish community. Beth Israel named the auditorium of its new building after Helen and Milton Smith in 1967. Helen served as international president of B’nai B’rith Women from 1974 to 1976, while Milton served as head of the Austin Jewish Federation and the Texas Jewish Historical Society

Political Engagement

Other Austin Jews became important civic leaders. Jeff Friedman was elected mayor of Austin in 1975 when he was only 30 years old. Known as the “hippy mayor,” Friedman ran on an environmentalist platform. Sherri Greenberg represented an Austin district in the state legislature from 1990 to 2000, while Elliot Naishtat represented Austin in the legislature from 1990 through 2016; both are Democrats.

Other Austin Jews became important civic leaders. Jeff Friedman was elected mayor of Austin in 1975 when he was only 30 years old. Known as the “hippy mayor,” Friedman ran on an environmentalist platform. Sherri Greenberg represented an Austin district in the state legislature from 1990 to 2000, while Elliot Naishtat represented Austin in the legislature from 1990 through 2016; both are Democrats.

Michael Dell

Michael Dell

Changes in the Community

By the 1980s, the Austin Jewish community started to change, as merchants like the Koens and manufacturers like the Smiths were joined by a new breed of Jewish businessmen who would transform Jewish life in the city. The most important of these arrived as a freshman at UT in 1983. Raised in Houston, Michael Dell had always been interested in computers. He dropped out of college in his freshman year to devote himself full-time to his start-up company, Dell Computer, which would help to usher in a high-tech renaissance in Austin. With Dell leading the way, Austin became a center of the high-tech industry in the 1980s and 1990s. What had been a medium-sized artsy college town became a booming metropolis; its Jewish community became one of the fastest growing in the country. Between 1980 and 1990, Austin’s Jewish population grew from 2100 to 5000. By 2002, an estimated 13,500 Jews lived in Austin; estimates in 2010 put the total number at 18,000. Community leaders anticipate this number doubling over the next 20 years as more and more Jews are drawn by the area’s economic opportunities, natural beauty, and laid-back charm.

Unlike Houston, Dallas, or San Antonio, Austin never really had any Jewish “merchant princes.” While many Austin Jews enjoyed economic success, none built the sort of large department store chains that emerged in these larger cities. High-tech industry executives, led by Michael Dell and the so-called “Dellionaires,” transformed Jewish philanthropy in Austin and reshaped the community’s institutional structure. In 1992, Michael and Susan Dell purchased a 40-acre parcel of land in northwest Austin as part of a plan to create a unified campus for the city’s Jewish community. Both Beth Israel and Agudas Achim were invited to move to the campus, which would also house a new and enlarged Jewish Community Center and the Austin Jewish Federation. While some in the Austin Jewish community opposed this plan, the Dell Campus opened in 2000. Agudas Achim, who had completed a new sanctuary and social hall in 1989, decided to build a new synagogue on the Dell Campus, which they dedicated in 2001 Agudas Achim has continued to grow along with the Austin Jewish community, and had over 500 member families in 2010.

Beth Israel debated for a long time about whether to relocate to the Dell Campus. Everyone agreed that the congregation, which grew from 360 families in 1985 to 682 in 1995, was too big for its current facility. This need was exacerbated when the sanctuary and other parts of the synagogue flooded after heavy rains in 1998. Beth Israel had already been holding High Holiday services at a local mega-church since their temple could not accommodate all of its worshipers. Although members voted to build a new synagogue on the Dell Campus, the deal fell through when congregation leaders could not come to an agreement with the Dell Campus Committee. Instead, Beth Israel decided to add on to its current building. Ultimately, Beth Israel wanted to maintain its own separate identity rather than consolidate within the Dell Campus

By the 1980s, the Austin Jewish community started to change, as merchants like the Koens and manufacturers like the Smiths were joined by a new breed of Jewish businessmen who would transform Jewish life in the city. The most important of these arrived as a freshman at UT in 1983. Raised in Houston, Michael Dell had always been interested in computers. He dropped out of college in his freshman year to devote himself full-time to his start-up company, Dell Computer, which would help to usher in a high-tech renaissance in Austin. With Dell leading the way, Austin became a center of the high-tech industry in the 1980s and 1990s. What had been a medium-sized artsy college town became a booming metropolis; its Jewish community became one of the fastest growing in the country. Between 1980 and 1990, Austin’s Jewish population grew from 2100 to 5000. By 2002, an estimated 13,500 Jews lived in Austin; estimates in 2010 put the total number at 18,000. Community leaders anticipate this number doubling over the next 20 years as more and more Jews are drawn by the area’s economic opportunities, natural beauty, and laid-back charm.

Unlike Houston, Dallas, or San Antonio, Austin never really had any Jewish “merchant princes.” While many Austin Jews enjoyed economic success, none built the sort of large department store chains that emerged in these larger cities. High-tech industry executives, led by Michael Dell and the so-called “Dellionaires,” transformed Jewish philanthropy in Austin and reshaped the community’s institutional structure. In 1992, Michael and Susan Dell purchased a 40-acre parcel of land in northwest Austin as part of a plan to create a unified campus for the city’s Jewish community. Both Beth Israel and Agudas Achim were invited to move to the campus, which would also house a new and enlarged Jewish Community Center and the Austin Jewish Federation. While some in the Austin Jewish community opposed this plan, the Dell Campus opened in 2000. Agudas Achim, who had completed a new sanctuary and social hall in 1989, decided to build a new synagogue on the Dell Campus, which they dedicated in 2001 Agudas Achim has continued to grow along with the Austin Jewish community, and had over 500 member families in 2010.

Beth Israel debated for a long time about whether to relocate to the Dell Campus. Everyone agreed that the congregation, which grew from 360 families in 1985 to 682 in 1995, was too big for its current facility. This need was exacerbated when the sanctuary and other parts of the synagogue flooded after heavy rains in 1998. Beth Israel had already been holding High Holiday services at a local mega-church since their temple could not accommodate all of its worshipers. Although members voted to build a new synagogue on the Dell Campus, the deal fell through when congregation leaders could not come to an agreement with the Dell Campus Committee. Instead, Beth Israel decided to add on to its current building. Ultimately, Beth Israel wanted to maintain its own separate identity rather than consolidate within the Dell Campus

The Jewish Community in Austin Today

In the 21st century, Austin has become a vibrant, diverse Jewish community with the resources of a large city. For much of its history, Austin had two synagogues, but in recent years a slew of new congregations have been established. The decision not to relocate led some Beth Israel members to break away and form another Reform congregation, Beth Shalom, which meets on the Dell Campus. By 2010, Beth Shalom had 390 member families, 200 children in their religious school, and a full-time rabbi. By 2010, there were ten Jewish congregations in Austin, including Tiferet Israel, an Orthodox shul, Shalom Rav, a Reconstructionist congregation, two Chabad centers, Shir Ami, an unaffiliated Reform congregation in the northern suburb of Cedar Park, the non-denominational Kol Halev, and Beth El, a conservative congregation unaffiliated with a national movement. Some of these new congregations meet at the Dell Campus. In 2006, Hillel dedicated a brand new building, the Topfer Center for Jewish Life, named after former Dell Vice-Chairman Mort Topfer and his wife Bobbi, who gave the lead gift. It serves the 5000 Jewish students who attend the University of Texas.

Today, the Dell Campus is the center of Austin’s Jewish community. In addition to the congregations, it is the home of the Jewish Community Center, the Austin Jewish Academy day school, and the Austin Jewish Federation. One can find kosher food at local grocery stores, as well as 21st century associations like the Firepit Minyan, which proclaims itself to be “unorthodox Judaism” and promises never to have a building or dues. Befitting of a high tech center, Austin is at the cutting edge of American Jewish life, and is poised to become one of the largest and most significant Jewish communities in the South.

Today, the Dell Campus is the center of Austin’s Jewish community. In addition to the congregations, it is the home of the Jewish Community Center, the Austin Jewish Academy day school, and the Austin Jewish Federation. One can find kosher food at local grocery stores, as well as 21st century associations like the Firepit Minyan, which proclaims itself to be “unorthodox Judaism” and promises never to have a building or dues. Befitting of a high tech center, Austin is at the cutting edge of American Jewish life, and is poised to become one of the largest and most significant Jewish communities in the South.

Sources

Schechter, Cathy. “Forty Acres and a Shul: ‘It’s Easy as Dell’,” in Hollace Ava Weiner & Kenneth D. Roseman, eds., Lone Stars of David: The Jews of Texas, Waltham: Brandeis University Press, 2007.

Silverberg, Jay Lawrence. “The First One Hundred Years: A History of the Austin Jewish Community, 1850-1950,” unpublished thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1974.

Silverberg, Jay Lawrence. “The First One Hundred Years: A History of the Austin Jewish Community, 1850-1950,” unpublished thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1974.