Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Bonham, Texas

Bonham: Historical Overview

Bonham’s Willow Wild Cemetery, located along 7th Street on the western outskirts of town, contains the last reminders of a Jewish community that has long since disappeared. Even in comparison to the oldest headstones at Willow Wild Cemetery, the Jewish section crumbles in relative disrepair. The grounds have been mowed in recent times by the local 4-H and Boy Scout troop, but for years this handful of stones from the late 19th and early 20th centuries was dwarfed by thick grasses, leaving them almost invisible to the passersby. The arrangement of the stones bespeaks the onetime optimism of a community at its peak: the few graves that exist are widely spaced, anticipating large family plots that would never come. The cemetery was created in 1881, and the last legible date on a tombstone is from 1908; the Jewish community as a whole seems to have disappeared by the 1930s.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Bonham

Broken headstones in Bonham's Jewish cemetery

Broken headstones in Bonham's Jewish cemetery

Early Settlers

As communities elsewhere in Texas were just getting started in the early 20th century, Bonham’s Jews were disappearing from the record. Bonham sits just shy of the Oklahoma border at the northern-most edge of the Texas Blackland Prairie. Settlers began arriving in the area in significant numbers in 1837 after the construction of Fort Inglish. After Texas gained its independence, Bailey Inglish led a group of settlers to the area they would call Bois D’Arc. Inglish constructed the two-story log-and-chinking fort as a safe haven to be used on the occasion of an Indian raid (a common occurrence at the time). In 1843, the settlement requested the name “Bloomington” before the Texas Congress, but Bonham was chosen instead as a memorial to James Butler Bonham, a fallen hero of the Alamo. Bonham exploded with economic growth following the construction of the Texas and Pacific Railroad in 1873, and factories and mills began to open up throughout the area.

The existence of a Jewish community in Bonham would be short-lived. Still, roughly through the years of 1860-1930, a small group of Jewish families did make the town their home. As was typical for Jews throughout the South, those who came to Bonham comprised much of the merchant class, with names such as Rosenbaum, Rhine, Englander, Klappholz, Cohen, Goldman, and Hermer gracing the town square throughout this 70-year period. Bonham never became home to enough Jews to host a congregation; those who wished to attend services either held them in private homes or traveled the 30 or so miles to Sherman, Texas. And, while some Jews did stay in Bonham for much of their lives, all of the families eventually left.

As communities elsewhere in Texas were just getting started in the early 20th century, Bonham’s Jews were disappearing from the record. Bonham sits just shy of the Oklahoma border at the northern-most edge of the Texas Blackland Prairie. Settlers began arriving in the area in significant numbers in 1837 after the construction of Fort Inglish. After Texas gained its independence, Bailey Inglish led a group of settlers to the area they would call Bois D’Arc. Inglish constructed the two-story log-and-chinking fort as a safe haven to be used on the occasion of an Indian raid (a common occurrence at the time). In 1843, the settlement requested the name “Bloomington” before the Texas Congress, but Bonham was chosen instead as a memorial to James Butler Bonham, a fallen hero of the Alamo. Bonham exploded with economic growth following the construction of the Texas and Pacific Railroad in 1873, and factories and mills began to open up throughout the area.

The existence of a Jewish community in Bonham would be short-lived. Still, roughly through the years of 1860-1930, a small group of Jewish families did make the town their home. As was typical for Jews throughout the South, those who came to Bonham comprised much of the merchant class, with names such as Rosenbaum, Rhine, Englander, Klappholz, Cohen, Goldman, and Hermer gracing the town square throughout this 70-year period. Bonham never became home to enough Jews to host a congregation; those who wished to attend services either held them in private homes or traveled the 30 or so miles to Sherman, Texas. And, while some Jews did stay in Bonham for much of their lives, all of the families eventually left.

Jewish Families in Bonham

David Rhine arrived in the United States from his native Bavaria in 1850, making his way to Bonham sometime in the 1860s. Rhine appears to have arrived alone, but, by 1874, census records show that he had wed his brother’s widow, Florence Rhine. Florence had a daughter named Eve from her previous marriage and the couple would go on to have three more children—all girls. Rhine fought for the Confederacy in Company A of the 16th Texas Cavalry during the Civil War, reaching the rank of Captain by 1863. After the war, the family earned a comfortable living in Bonham as the owners of a dry goods retailer known for its imported goods and “bric-a-brac from around the world.”

By the mid-1870s, the Rhine family was able to construct a lavish estate at 404 East 8th Street—a patch of the former Bailey Inglish property. No known pictures remain of the home as it existed under the Rhines' ownership; the home went into possession of the Rhines' youngest daughter, Fridora, until 1912, when it was sold to Eugene Risser. Risser remodeled the exterior of the house, adding a porch. In recent years, the building burned to the ground, leaving only a sparsely wooded vacant lot.

Other Rhines lived and did business in Bonham. It appears that two men named Abraham and Samuel Rhine may once have owned and operated a store in downtown Bonham rather early in the city’s history. Records of commerce mention the firm of S. and A. Rhine as the previous owners of a store sold to one J.R. Russell in 1854. Another early Jewish resident was Henry Levine, who had moved to Bonham by 1878, opening a store. His brother Marks lived with Levine’s young family in 1880, working in the store as a bookkeeper.

David Rhine arrived in the United States from his native Bavaria in 1850, making his way to Bonham sometime in the 1860s. Rhine appears to have arrived alone, but, by 1874, census records show that he had wed his brother’s widow, Florence Rhine. Florence had a daughter named Eve from her previous marriage and the couple would go on to have three more children—all girls. Rhine fought for the Confederacy in Company A of the 16th Texas Cavalry during the Civil War, reaching the rank of Captain by 1863. After the war, the family earned a comfortable living in Bonham as the owners of a dry goods retailer known for its imported goods and “bric-a-brac from around the world.”

By the mid-1870s, the Rhine family was able to construct a lavish estate at 404 East 8th Street—a patch of the former Bailey Inglish property. No known pictures remain of the home as it existed under the Rhines' ownership; the home went into possession of the Rhines' youngest daughter, Fridora, until 1912, when it was sold to Eugene Risser. Risser remodeled the exterior of the house, adding a porch. In recent years, the building burned to the ground, leaving only a sparsely wooded vacant lot.

Other Rhines lived and did business in Bonham. It appears that two men named Abraham and Samuel Rhine may once have owned and operated a store in downtown Bonham rather early in the city’s history. Records of commerce mention the firm of S. and A. Rhine as the previous owners of a store sold to one J.R. Russell in 1854. Another early Jewish resident was Henry Levine, who had moved to Bonham by 1878, opening a store. His brother Marks lived with Levine’s young family in 1880, working in the store as a bookkeeper.

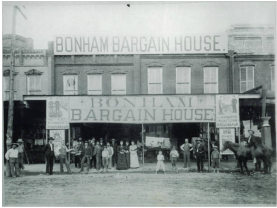

Morris Rosenbaum's Bonham Bargain House

Morris Rosenbaum's Bonham Bargain House

Perhaps the most prominent Jewish family in Bonham was the Rosenbaums. Morris Rosenbaum left Prussia for the United States in 1861. The first of the Rosenbaum family to settle in Bonham, Morris soon became a successful merchant. His store, the Bonham Bargain House, was located on South Main Street. Morris and his wife, Elizabeth, had five children, at least one of whom helped out as a salesman in the family store. Both Morris and Elizabeth Rosenbaum are remembered as civic leaders in Bonham; an 1882 county commissioner’s report stated that Rosenbaum and Henry Levine had charitably “furnished goods for the support of a pauper.” Along with a man named R.W. Campbell, Rosenbaum also donated several lots of land for the price of $1.00. The city then used these lots as the site of the community waterworks. Alongside the retail business, Rosenbaum was also a cotton buyer and one of the original stockholders in the First National Bank. Despite their involvement in Bonham’s civic life, the Rosenbaum family had left the town by 1910.

Many of the Jews of this early community have fallen through the cracks in the written record. Cohen and Goldberg’s Cheap Clothing store appears in an old photograph (circa 1890) of businesses along the town square. Later, this store was purchased by Morris Rosenbaum. Cohen and Goldberg’s store seemed to be short-lived, and there is little about them or their families in the historical record. Neither are buried in the local Jewish cemetery, so they most likely moved on to another town after a few years in Bonham. The Klappholz family were also short-lived Bonham residents. J. Klappholz owned a local bargain store, while his young son Adolph is buried in the Bonham Jewish cemetery. Cohen, Goldberg, and the Klappholz family seem to have left Bonham by the time of the 1900 census.

Many of the Jews of this early community have fallen through the cracks in the written record. Cohen and Goldberg’s Cheap Clothing store appears in an old photograph (circa 1890) of businesses along the town square. Later, this store was purchased by Morris Rosenbaum. Cohen and Goldberg’s store seemed to be short-lived, and there is little about them or their families in the historical record. Neither are buried in the local Jewish cemetery, so they most likely moved on to another town after a few years in Bonham. The Klappholz family were also short-lived Bonham residents. J. Klappholz owned a local bargain store, while his young son Adolph is buried in the Bonham Jewish cemetery. Cohen, Goldberg, and the Klappholz family seem to have left Bonham by the time of the 1900 census.

The Jewish Community in Bonham Today

The Bonham Jewish community was never large, and never organized Jewish institutions beyond the small burial ground outside of town. For this small group of Jews, Bonham provided a measure of economic opportunity for a time, although they moved on once they found greater prospects elsewhere. There is no Jewish community in Bonham today.