Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Breckenridge, Texas

Breckenridge: Historical Overview

Founded in 1876, Breckenridge was a small sleepy West Texas town for its first 40 years. By 1900, only 531 people lived in the seat of rural Stephens County, none of whom were Jews. But when oil was discovered in the area in the late 1910s, Breckenridge was transformed into a classic boomtown, growing from 1,500 residents to over 30,000 within one year. During 1920, the height of the local oil rush, 200 wells were installed within the city limits and a railroad was built through the town.

While the oil boom was short-lived, fizzling out by the mid-1920s, it left behind a small but thriving commercial center along with a Jewish community to match. While there is no longer a Jewish community in Breckenridge today, Jews played an important part in the town's history.

While the oil boom was short-lived, fizzling out by the mid-1920s, it left behind a small but thriving commercial center along with a Jewish community to match. While there is no longer a Jewish community in Breckenridge today, Jews played an important part in the town's history.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Breckenridge

Early Jewish Residents

The first Jews to settle in Breckenridge, Hungarian-native Nathan Winkler, his wife Annie, and their three small children, arrived in 1920 from Fort Stockton, Texas. Nathan opened a dry goods store to cater to the tremendous number of oil workers and fortune seekers moving to Breckenridge. The second Jewish family to settle in Breckenridge was that of Charles and Bertha Bender, who moved their dry goods business from Lubbock to the oil boom town later in 1920. Soon after, a number of Jewish-owned stores popped up on Walker Street in downtown, including S. Segal and Co., owned by Sam Segal and Nate Rosenbaum, Baron Brothers Department Store, Toby’s Quality Store, owned by David Tobolowsky, and Alhambra Confectionary, co-owned by Simon Fram and Benjamin Karelitz. The local newspaper later noted in 1929 that the presence of so many Jewish merchants was a sign of the town’s economic vitality, writing “water and oil may not mix, but Jews and prosperity do. The presence of Jews in any and every community is a sign of hope and promise...Jews do not stay in dead towns.”

The first Jews to settle in Breckenridge, Hungarian-native Nathan Winkler, his wife Annie, and their three small children, arrived in 1920 from Fort Stockton, Texas. Nathan opened a dry goods store to cater to the tremendous number of oil workers and fortune seekers moving to Breckenridge. The second Jewish family to settle in Breckenridge was that of Charles and Bertha Bender, who moved their dry goods business from Lubbock to the oil boom town later in 1920. Soon after, a number of Jewish-owned stores popped up on Walker Street in downtown, including S. Segal and Co., owned by Sam Segal and Nate Rosenbaum, Baron Brothers Department Store, Toby’s Quality Store, owned by David Tobolowsky, and Alhambra Confectionary, co-owned by Simon Fram and Benjamin Karelitz. The local newspaper later noted in 1929 that the presence of so many Jewish merchants was a sign of the town’s economic vitality, writing “water and oil may not mix, but Jews and prosperity do. The presence of Jews in any and every community is a sign of hope and promise...Jews do not stay in dead towns.”

Dedication banquet for Beth Israel's synagogue in 1929

Dedication banquet for Beth Israel's synagogue in 1929

Organized Jewish Life in Breckenridge

This growing number of Jews soon began to organize under the leadership of Charles and Bertha Bender. First, the men established a B’nai B’rith lodge, while women founded a Hadassah chapter. Bertha Bender served as president of the chapter, which attracted members from such small towns as Cisco, Eastland, and Ranger. Breckenridge Jews would worship together in private homes during these early years; most would travel to Fort Worth, 100 miles away, for High Holiday services. The B’nai B’rith chapter led the way in organizing a congregation, which they established as Beth Israel by the late 1920s.

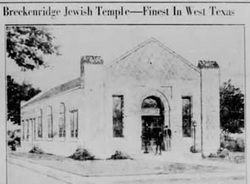

In conjunction with the creation of a formal congregation, Breckenridge Jews also began to push for the construction of a permanent house of worship. Charles Bender was head of the synagogue building committee, which solicited donations from Jewish organizations and congregations around the country, receiving donations from New York, Boston, and Los Angeles. Local Gentiles also contributed to the building fund, which raised $25,000. Bender singled out the support of these non-Jews, telling the local newspaper “without their help we could not have built the church which we are all so proud of.” The synagogue was dedicated in 1929 in a public ceremony featuring Mayor Charles Clark and local Christian ministers. According to local newspaper reports, 500 people crowded into the small synagogue for the three hour ceremony. Rabbi Abraham Bengis of Fort Worth’s Orthodox congregation was the keynote speaker for the dedication. Rabbis from Dallas, both Reform and Orthodox, also took part in the event. That evening, Beth Israel held a banquet dinner, with Rabbi H. Raphael Gold of Dallas as the featured speaker.

At the time of the synagogue dedication, about 60 Jews lived in Breckenridge. Beth Israel had 15 member families and ten individual members, including a few from surrounding towns. Of 20 members who could be found in the 1930 census, 70% owned a business, primarily dry goods or jewelry stores. They also owned grocery stores and junk businesses. While a large majority owned a business, only 35% owned their homes. Most were either boarders or renters. This relatively low figure of home ownership is not surprising since none of the members had been in Breckenridge for more than nine years, and many would soon move on to other cities. Only a slight majority, 55%, of members were foreign-born, most all from Russia or Poland. Their average year of immigration was 1906, meaning most had been in the U.S. for over 20 years. Almost half were born in America, though only one was a native Texan. Most came from the Midwest or the Northeast. In its early years, Beth Israel held Friday night services each week, usually lay-led. Sometimes they would bring in visiting rabbis from Fort Worth, Waco, or San Antonio to lead services, though they never had a full-time rabbi. While the local newspaper called Beth Israel a “modern Orthodox” congregation in 1929, their services included both Hebrew and English prayers, and men and women sat together. In practice, Beth Israel was closer to Conservative Judaism.

This growing number of Jews soon began to organize under the leadership of Charles and Bertha Bender. First, the men established a B’nai B’rith lodge, while women founded a Hadassah chapter. Bertha Bender served as president of the chapter, which attracted members from such small towns as Cisco, Eastland, and Ranger. Breckenridge Jews would worship together in private homes during these early years; most would travel to Fort Worth, 100 miles away, for High Holiday services. The B’nai B’rith chapter led the way in organizing a congregation, which they established as Beth Israel by the late 1920s.

In conjunction with the creation of a formal congregation, Breckenridge Jews also began to push for the construction of a permanent house of worship. Charles Bender was head of the synagogue building committee, which solicited donations from Jewish organizations and congregations around the country, receiving donations from New York, Boston, and Los Angeles. Local Gentiles also contributed to the building fund, which raised $25,000. Bender singled out the support of these non-Jews, telling the local newspaper “without their help we could not have built the church which we are all so proud of.” The synagogue was dedicated in 1929 in a public ceremony featuring Mayor Charles Clark and local Christian ministers. According to local newspaper reports, 500 people crowded into the small synagogue for the three hour ceremony. Rabbi Abraham Bengis of Fort Worth’s Orthodox congregation was the keynote speaker for the dedication. Rabbis from Dallas, both Reform and Orthodox, also took part in the event. That evening, Beth Israel held a banquet dinner, with Rabbi H. Raphael Gold of Dallas as the featured speaker.

At the time of the synagogue dedication, about 60 Jews lived in Breckenridge. Beth Israel had 15 member families and ten individual members, including a few from surrounding towns. Of 20 members who could be found in the 1930 census, 70% owned a business, primarily dry goods or jewelry stores. They also owned grocery stores and junk businesses. While a large majority owned a business, only 35% owned their homes. Most were either boarders or renters. This relatively low figure of home ownership is not surprising since none of the members had been in Breckenridge for more than nine years, and many would soon move on to other cities. Only a slight majority, 55%, of members were foreign-born, most all from Russia or Poland. Their average year of immigration was 1906, meaning most had been in the U.S. for over 20 years. Almost half were born in America, though only one was a native Texan. Most came from the Midwest or the Northeast. In its early years, Beth Israel held Friday night services each week, usually lay-led. Sometimes they would bring in visiting rabbis from Fort Worth, Waco, or San Antonio to lead services, though they never had a full-time rabbi. While the local newspaper called Beth Israel a “modern Orthodox” congregation in 1929, their services included both Hebrew and English prayers, and men and women sat together. In practice, Beth Israel was closer to Conservative Judaism.

Zionism in Breckenridge

During the dedication ceremony for Beth Israel’s new synagogue in 1929, Louis Freed, president of the Texas Zionist Association, gave a speech about the history of the Zionism Movement. Bertha Bender, the head of the local Hadassah chapter, and Nathan Winkler, president of the local Zionist organization, also gave speeches during the dedication. Indeed, from its beginning, the Breckenridge Jewish community was strongly Zionist. Charles Bender became a colorful leader of the movement in the state, serving as president of the Texas Zionist Association in 1938. He attended the World Zionist Congress in Switzerland as a delegate in 1929 and 1931. Bender’s sons spent time living in Palestine after they finished high school. After Israel was established in 1948, Bender would visit the Jewish state wearing a cowboy hat and boots, leading Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion to dub Bender the “Jewish Cowboy from Texas.” Bender wasn’t the only Breckenridge Jew who mixed their support for Zionism with their Texas identity. In the 1950s, Albert Tuck would take part in the local rodeo parade, carrying an Israeli flag while riding on horseback through downtown Breckenridge. His wife Tillie was president of the local Hadassah chapter for several decades. Most of the focus of Breckenridge’s Zionist groups was on raising money. Soon after arriving in Breckenridge in 1920, Charles Bender started a campaign to raise money for the Keren Hayesod, which supported the Jewish settlement in Palestine. In the early 1950s, Charles Bender and his wife Bertha donated money to build a science laboratory at the Technion in Haifa.

During the dedication ceremony for Beth Israel’s new synagogue in 1929, Louis Freed, president of the Texas Zionist Association, gave a speech about the history of the Zionism Movement. Bertha Bender, the head of the local Hadassah chapter, and Nathan Winkler, president of the local Zionist organization, also gave speeches during the dedication. Indeed, from its beginning, the Breckenridge Jewish community was strongly Zionist. Charles Bender became a colorful leader of the movement in the state, serving as president of the Texas Zionist Association in 1938. He attended the World Zionist Congress in Switzerland as a delegate in 1929 and 1931. Bender’s sons spent time living in Palestine after they finished high school. After Israel was established in 1948, Bender would visit the Jewish state wearing a cowboy hat and boots, leading Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion to dub Bender the “Jewish Cowboy from Texas.” Bender wasn’t the only Breckenridge Jew who mixed their support for Zionism with their Texas identity. In the 1950s, Albert Tuck would take part in the local rodeo parade, carrying an Israeli flag while riding on horseback through downtown Breckenridge. His wife Tillie was president of the local Hadassah chapter for several decades. Most of the focus of Breckenridge’s Zionist groups was on raising money. Soon after arriving in Breckenridge in 1920, Charles Bender started a campaign to raise money for the Keren Hayesod, which supported the Jewish settlement in Palestine. In the early 1950s, Charles Bender and his wife Bertha donated money to build a science laboratory at the Technion in Haifa.

Charles & Bertha Bender with their family

Charles & Bertha Bender with their family

After the Oil Boom

Once the oil boom dried up, Breckenridge lost much of its economic appeal. Its population dropped to 5,826 people in 1940, and it has not grown since. Several of the founders of Beth Israel, such as Nathan Winkler and Sam Segal, moved away in search of greater opportunities, though a handful of Jewish families continued to call Breckenridge home. In 1937, 80 Jews lived in town while there were still about eight Jewish-owned businesses in Breckenridge. Bender’s Department Store, run by Charles and Bertha, continued to flourish during the Depression years. The store remained in business until the couple retired and sold it in 1953. Rae Scheinberg took over her husband Israel’s clothing store after he died in 1931. She later married Jake Socol, and the two opened the Popular Store in 1946. Jake’s daughter and son-in-law, Mickey and Harry Shapiro, moved to Breckenridge to help run the department store. Run by the Socol and Shapiro families, the Popular Store remained in business until it closed in 1987. Simon Fram and Ben Karelitz closed their confectionery store in the early 1940s, though Simon later opened Fram’s, a men’s clothing store.

Not all Breckenridge Jews owned downtown stores. Otto Bendorf moved to Breckenridge in the 1930s, opening a successful oil field supply business. Otto’s cousin, Werner Bendorf, escaped Nazi Germany and was hidden in a family’s house in Holland throughout the war years. Otto arranged for Werner and his family to come to Breckenridge after the war, and employed him in his oil field supply business. Albert Tuck moved to Breckenridge during World War II and ran a scrap metal business, which he later bought. His wife Tillie spent many years as a public school teacher in Breckenridge.

Breckenridge Jews were closely integrated within the larger community. The Breckenridge American newspaper noted in 1929 that Jews had donated money to several local churches and the YMCA. When St. Andrews Episcopal Church was being built in 1950, Beth Israel let the congregation use their synagogue for services. In addition to his commitment to Zionism, Charles Bender served on the board of the YMCA and was active in the local Lions Club and Masonic lodge. Bender was noted for his charitable works, including giving shoes away to needy children of all races.

Once the oil boom dried up, Breckenridge lost much of its economic appeal. Its population dropped to 5,826 people in 1940, and it has not grown since. Several of the founders of Beth Israel, such as Nathan Winkler and Sam Segal, moved away in search of greater opportunities, though a handful of Jewish families continued to call Breckenridge home. In 1937, 80 Jews lived in town while there were still about eight Jewish-owned businesses in Breckenridge. Bender’s Department Store, run by Charles and Bertha, continued to flourish during the Depression years. The store remained in business until the couple retired and sold it in 1953. Rae Scheinberg took over her husband Israel’s clothing store after he died in 1931. She later married Jake Socol, and the two opened the Popular Store in 1946. Jake’s daughter and son-in-law, Mickey and Harry Shapiro, moved to Breckenridge to help run the department store. Run by the Socol and Shapiro families, the Popular Store remained in business until it closed in 1987. Simon Fram and Ben Karelitz closed their confectionery store in the early 1940s, though Simon later opened Fram’s, a men’s clothing store.

Not all Breckenridge Jews owned downtown stores. Otto Bendorf moved to Breckenridge in the 1930s, opening a successful oil field supply business. Otto’s cousin, Werner Bendorf, escaped Nazi Germany and was hidden in a family’s house in Holland throughout the war years. Otto arranged for Werner and his family to come to Breckenridge after the war, and employed him in his oil field supply business. Albert Tuck moved to Breckenridge during World War II and ran a scrap metal business, which he later bought. His wife Tillie spent many years as a public school teacher in Breckenridge.

Breckenridge Jews were closely integrated within the larger community. The Breckenridge American newspaper noted in 1929 that Jews had donated money to several local churches and the YMCA. When St. Andrews Episcopal Church was being built in 1950, Beth Israel let the congregation use their synagogue for services. In addition to his commitment to Zionism, Charles Bender served on the board of the YMCA and was active in the local Lions Club and Masonic lodge. Bender was noted for his charitable works, including giving shoes away to needy children of all races.

The Mid-20th Century

During the 1950s, the Breckenridge Jewish community consisted of about ten families. In the early part of the decade, Beth Israel held services infrequently, yet they would bring in visiting clergy for the High Holidays. In 1949, Cantor Solomon Pines led Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services at Beth Israel. By the mid-1950s, the congregation had brought back weekly Friday night services, with members taking turns leading the Shabbat prayers. By this time, Beth Israel was still traditional if not Orthodox, celebrating Rosh Hashanah for two days and requiring a minyan before certain prayers could be recited, yet only one family in the congregation kept strict kosher. There was not a regular religious school, as parents would drive their children to Fort Worth to attend Sunday school at Ahavath Shalom. Although the congregation was small, it was close-knit. Members would gather for dinner at Charles and Bertha Bender’s house prior to Rosh Hashanah services each year.

During the 1950s, the Breckenridge Jewish community consisted of about ten families. In the early part of the decade, Beth Israel held services infrequently, yet they would bring in visiting clergy for the High Holidays. In 1949, Cantor Solomon Pines led Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur services at Beth Israel. By the mid-1950s, the congregation had brought back weekly Friday night services, with members taking turns leading the Shabbat prayers. By this time, Beth Israel was still traditional if not Orthodox, celebrating Rosh Hashanah for two days and requiring a minyan before certain prayers could be recited, yet only one family in the congregation kept strict kosher. There was not a regular religious school, as parents would drive their children to Fort Worth to attend Sunday school at Ahavath Shalom. Although the congregation was small, it was close-knit. Members would gather for dinner at Charles and Bertha Bender’s house prior to Rosh Hashanah services each year.

The Jewish Community in Breckenridge Today

Beth Israel's former synagogue c. 2012.

Beth Israel's former synagogue c. 2012.

The Jewish children raised in Breckenridge in the 1950s did not stay in town once they got older. By the 1970s, most of the Jewish-owned businesses in town had closed as the next generation decided to move elsewhere rather than stay and run the family business. Albert and Tillie Tuck sold their scrap metal business in the early 1970s and moved to Memphis, Tennessee, to be with their children. Marvin Socol, who ran the Popular Store until it closed in 1987 and later moved to Dallas, was the last Jew to live in Breckenridge. The former Beth Israel synagogue building remained as a testament to Breckenridge's Jewish history until it burned to the ground early in the morning of November 24, 2019.