Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Brownsville, Texas

Brownsville: Historical Overview

|

As the state’s southernmost city, Brownsville, Texas, located mere feet from the bustling city of Matamoros, Mexico, may seem to be an unlikely place for Jews to settle. Nonetheless, the history of the Jewish community of Brownsville is a complex one, intricately tied with the dynamic of a Mexican-American border city, the quest of small Jewish communities for “official” status and formal leadership, the struggle of remote congregations to survive and expand, and even a few incidents of western gun slinging. From the arrival of the first Jewish immigrants around the time of the Mexican-American War to the formation and growth of synagogue Beth-El, many notable individuals have helped carve a Jewish niche in a distinctly Mexican-American city.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Brownsville

International bridge between Brownsville

International bridge between Brownsville and Matamoros, Mexico

Early Settlers

Early Jewish residents played a key role in Brownsville’s creation. Simon Mussina, a Dutch Jew, arrived in Matamoros, Mexico, in 1845 and purchased the Matamoros newspaper the American Flag, which moved to Brownsville in 1848. In 1846, as the Mexican-American War broke out, Mussina purchased formerly Mexican-owned land which after the war was declared part of the United States; his property soon became the city of Brownsville and he is considered one of the city’s founders.

John Melvin Hirsch, an early Jewish resident of Brownsville and a friend of General Zachary Taylor, was forced to move across the border during the conflict, as General Taylor used the Hirsch family home as a military headquarters. Another Jew instrumental to Brownsville’s formation was Leopold Schlinger, who came to the United States from Austria in 1847. He moved to Brownsville before the Civil War, though relocated to Matamoros after the war broke out, due to his Unionist sympathies. After the war, Schlinger returned to Brownsville and was appointed a county commissioner in 1868.

The first Jew to be buried in Brownsville was Joseph Moses, a New York-born merchant, who died in the yellow fever epidemic of 1858. His brother Benjamin had been in Brownsville in 1846, shipping cargo for General Taylor’s army.

Between the Mexican-American War and the Civil War, most Jews who moved to the area resided in Matamoros. During the Civil War, a handful of Jewish merchants from Galveston moved to Matamoros to get around the Union blockade of Confederate ports. However, with the end of the war and the decline in the cotton economy, most of these families moved either to Brownsville or elsewhere.

Early Jewish residents played a key role in Brownsville’s creation. Simon Mussina, a Dutch Jew, arrived in Matamoros, Mexico, in 1845 and purchased the Matamoros newspaper the American Flag, which moved to Brownsville in 1848. In 1846, as the Mexican-American War broke out, Mussina purchased formerly Mexican-owned land which after the war was declared part of the United States; his property soon became the city of Brownsville and he is considered one of the city’s founders.

John Melvin Hirsch, an early Jewish resident of Brownsville and a friend of General Zachary Taylor, was forced to move across the border during the conflict, as General Taylor used the Hirsch family home as a military headquarters. Another Jew instrumental to Brownsville’s formation was Leopold Schlinger, who came to the United States from Austria in 1847. He moved to Brownsville before the Civil War, though relocated to Matamoros after the war broke out, due to his Unionist sympathies. After the war, Schlinger returned to Brownsville and was appointed a county commissioner in 1868.

The first Jew to be buried in Brownsville was Joseph Moses, a New York-born merchant, who died in the yellow fever epidemic of 1858. His brother Benjamin had been in Brownsville in 1846, shipping cargo for General Taylor’s army.

Between the Mexican-American War and the Civil War, most Jews who moved to the area resided in Matamoros. During the Civil War, a handful of Jewish merchants from Galveston moved to Matamoros to get around the Union blockade of Confederate ports. However, with the end of the war and the decline in the cotton economy, most of these families moved either to Brownsville or elsewhere.

Brownsville's downtown business district

Brownsville's downtown business district

Among those who settled in Brownsville were Arthur S. Wolff, later a city physician and quarantine officer, and Louis Wise, former Union Army surgeon and soldier. A French native and former Confederate Soldier, Adolph Bollack, who fought in the final battle of the Civil War just outside of Brownsville (nearly a month after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse), returned to town in 1869 with the Torah his family had brought from France. Perhaps it is the same scroll which was reportedly kept in Matamoros in 1876 and in 1882 was the focus of a humorous incident in which Mexican border guards refused to touch the Torah as it was moved across the border for a Friday night service in Brownsville out of fear of touching the “Jewish god.”

In 1868, Charles Stillman, the (non-Jewish) founder of Brownsville, deeded a plot for a Jewish cemetery to the newly formed Hebrew Benevolent Society. One of the first people buried in the cemetery was Joseph Alexander, a prominent dry goods merchant and leader of the local Jewish community who was shot and killed by a bandit 22 miles outside of Brownsville while on his way to Rio Grande City in 1872. In 1868 or 1869, Joseph Moses’ grave was moved from the city cemetery to the new Jewish one.

In 1868, Charles Stillman, the (non-Jewish) founder of Brownsville, deeded a plot for a Jewish cemetery to the newly formed Hebrew Benevolent Society. One of the first people buried in the cemetery was Joseph Alexander, a prominent dry goods merchant and leader of the local Jewish community who was shot and killed by a bandit 22 miles outside of Brownsville while on his way to Rio Grande City in 1872. In 1868 or 1869, Joseph Moses’ grave was moved from the city cemetery to the new Jewish one.

Civic Life

Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, Jews cemented themselves as prominent figures in Brownsville’s political and economic life. While only ten Jews lived in Brownsville in 1876, with another 15 in Matamoros, they were among the area’s leading merchants. Firms like Bloomberg and Raphael and A. Marks & Brother became very successful. Jewish businessmen were so prominent in Brownsville that on the first day of Rosh Hashanah in 1902 the Brownsville Daily Herald reported: “The town looks somewhat dull today, with the stores and offices of all Jewish business firms closed. Our Jewish friends [are] celebrating Rosh Hashanah today, suspending all business and enjoying feasts.”

Brownsville Jews were also active in civic life, with G.M. Raphael serving as acting mayor in 1876, Louis Cowen as city secretary, and Sol Ashheim as county treasurer. Around the turn of the century, Jews served as the first president of the Brownsville Rotary Club, leader of a Democratic Party organization, alderman, city council member, Grand Master of the Masonic Order, county treasurer, and county District Clerk. Notably, Max Stein, a popular store owner from about 35 miles outside of Brownsville was appointed to fill an open seat as a county judge; Stein was shot in 1890, allegedly by the wife of the replaced judge. Benjamin Kowalski’s venture into politics was far less tragic; he was elected Brownsville’s mayor in 1912. Around the same time, in the midst of the Mexican Revolution, Oscar Sommer, later a prominent Brownsville and Matamoros citizen, distinguished himself by transporting wounded soldiers to the Brownsville hospital and working to reclaim hostages. Sommer’s wife Laura would later found the local chapter of Hadassah in 1954. Clearly, the Jews of Brownsville were accepted by their neighbors, as they repeatedly distinguished themselves publicly and were chosen or elected to important civic positions

Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, Jews cemented themselves as prominent figures in Brownsville’s political and economic life. While only ten Jews lived in Brownsville in 1876, with another 15 in Matamoros, they were among the area’s leading merchants. Firms like Bloomberg and Raphael and A. Marks & Brother became very successful. Jewish businessmen were so prominent in Brownsville that on the first day of Rosh Hashanah in 1902 the Brownsville Daily Herald reported: “The town looks somewhat dull today, with the stores and offices of all Jewish business firms closed. Our Jewish friends [are] celebrating Rosh Hashanah today, suspending all business and enjoying feasts.”

Brownsville Jews were also active in civic life, with G.M. Raphael serving as acting mayor in 1876, Louis Cowen as city secretary, and Sol Ashheim as county treasurer. Around the turn of the century, Jews served as the first president of the Brownsville Rotary Club, leader of a Democratic Party organization, alderman, city council member, Grand Master of the Masonic Order, county treasurer, and county District Clerk. Notably, Max Stein, a popular store owner from about 35 miles outside of Brownsville was appointed to fill an open seat as a county judge; Stein was shot in 1890, allegedly by the wife of the replaced judge. Benjamin Kowalski’s venture into politics was far less tragic; he was elected Brownsville’s mayor in 1912. Around the same time, in the midst of the Mexican Revolution, Oscar Sommer, later a prominent Brownsville and Matamoros citizen, distinguished himself by transporting wounded soldiers to the Brownsville hospital and working to reclaim hostages. Sommer’s wife Laura would later found the local chapter of Hadassah in 1954. Clearly, the Jews of Brownsville were accepted by their neighbors, as they repeatedly distinguished themselves publicly and were chosen or elected to important civic positions

Beth-El's first synagogue.

Beth-El's first synagogue. Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler.

Organized Jewish Life in Brownsville

Brownsville’s Jewish community grew steadily and began to formally organize itself in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. According to a letter from Rabbi Abraham Blum of Galveston, by 1882 the Jewish populations of Matamoros and Brownsville totaled 50 people and had established a Sunday school. From the 1870s to the early 1920s, High Holy Day services were held at the home of Henry and Pauline Bollack, German immigrants and general store owners. In 1929, the deed to the cemetery was transferred to the newly established Hebrew Cemetery Association of Brownsville. By the late 1920s, with the community numbered approximately 24 families. Friday night services were held at the American Legion Hall, with High Holy Day services and a Sunday School, organized by Mrs. Jacob Grunewald, held at the Masonic Temple.

The Jews of Brownsville desired to build a synagogue of their own, especially parents concerned for the Jewish upbringing of their children. Without a regular Hebrew service, some Brownsville Jews had taken up the habit of attending services at the Episcopal or Catholic church. A group of Jewish women led this organizing effort, establishing a Sisterhood in 1931. Around the same time, a congregation, Beth-El was founded. The Sisterhood raised money and purchased land for the construction of a synagogue, which was completed by 1932.

Even before the construction of the synagogue, Brownsville’s Jewish community had strong internal leadership. From 1926 until the 1970s, clothing merchant and community member Sam Perl led Friday night services and served as lay-leader for the Brownsville community. Perl functioned as an ordained rabbi would, officiating at various life cycle events. Recognizing the diversity of his congregation, with a mix of Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform Jews from Europe, Latin America, and across the United States, Perl took a religious approach that would satisfy as many congregants as possible, though he nonetheless remained open to change. For example, throughout World War II, Temple Beth-El welcomed Jewish servicemen stationed near Brownsville. However, many of these soldiers had backgrounds rooted in more traditional Judaism; in order to suit their request that Hebrew be incorporated into the service, a soldier began sharing the bimah with Perl, who began, at the soldiers’ request, to wear a tallit (traditional prayer shawl) and kippah (traditional head covering) while leading the service. When the soldiers returned home, the service returned to an English-only format, but Perl continued to wear the prayer garments provided by the Jewish Welfare Board.

Brownsville’s Jewish community grew steadily and began to formally organize itself in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. According to a letter from Rabbi Abraham Blum of Galveston, by 1882 the Jewish populations of Matamoros and Brownsville totaled 50 people and had established a Sunday school. From the 1870s to the early 1920s, High Holy Day services were held at the home of Henry and Pauline Bollack, German immigrants and general store owners. In 1929, the deed to the cemetery was transferred to the newly established Hebrew Cemetery Association of Brownsville. By the late 1920s, with the community numbered approximately 24 families. Friday night services were held at the American Legion Hall, with High Holy Day services and a Sunday School, organized by Mrs. Jacob Grunewald, held at the Masonic Temple.

The Jews of Brownsville desired to build a synagogue of their own, especially parents concerned for the Jewish upbringing of their children. Without a regular Hebrew service, some Brownsville Jews had taken up the habit of attending services at the Episcopal or Catholic church. A group of Jewish women led this organizing effort, establishing a Sisterhood in 1931. Around the same time, a congregation, Beth-El was founded. The Sisterhood raised money and purchased land for the construction of a synagogue, which was completed by 1932.

Even before the construction of the synagogue, Brownsville’s Jewish community had strong internal leadership. From 1926 until the 1970s, clothing merchant and community member Sam Perl led Friday night services and served as lay-leader for the Brownsville community. Perl functioned as an ordained rabbi would, officiating at various life cycle events. Recognizing the diversity of his congregation, with a mix of Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform Jews from Europe, Latin America, and across the United States, Perl took a religious approach that would satisfy as many congregants as possible, though he nonetheless remained open to change. For example, throughout World War II, Temple Beth-El welcomed Jewish servicemen stationed near Brownsville. However, many of these soldiers had backgrounds rooted in more traditional Judaism; in order to suit their request that Hebrew be incorporated into the service, a soldier began sharing the bimah with Perl, who began, at the soldiers’ request, to wear a tallit (traditional prayer shawl) and kippah (traditional head covering) while leading the service. When the soldiers returned home, the service returned to an English-only format, but Perl continued to wear the prayer garments provided by the Jewish Welfare Board.

Beth-El's current building, dedicated in 1951.

Beth-El's current building, dedicated in 1951. Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Upon the conclusion of World War II, Temple Beth-El began focusing on acquiring a new space, as the original building no longer suited the needs of the growing congregation. The original building also housed the congregation’s religious school, which, under the direction of Sam Perl’s sister-in-law Corrine Perl, had ten students divided into three grades in its first class in 1933. However, by 1951, for a community of 35 families, the old building was too small for large events such as weddings. The members of Beth-El decided to construct a social hall. Thanks to the efforts of Sam Perl, who organized fundraising poker games after Friday night services, and a generous donation from Julia Wood, with the stipulation that the new facility be named for her mother, the Pauline Bollack Memorial Building was completed in 1951.

Ruben Edelstein played a key role in putting Beth-El on a strong financial footing, gaining tax-exempt status for the congregation. When the cemetery fell into disrepair, Edelstein was appointed to oversee the burial ground. Edelstein also served as assistant lay leader from the 1950s to 1975, and later served as temple president. Thanks to Edelstein’s leadership, when two lots adjacent to the synagogue became available in 1955, the congregation was able to purchase both. They constructed a new religious school building in 1956, completing it three months before Beth-El’s 25th anniversary. Edelstein was also a leader in the larger community, serving as mayor from 1975 to 1979.

Ruben Edelstein played a key role in putting Beth-El on a strong financial footing, gaining tax-exempt status for the congregation. When the cemetery fell into disrepair, Edelstein was appointed to oversee the burial ground. Edelstein also served as assistant lay leader from the 1950s to 1975, and later served as temple president. Thanks to Edelstein’s leadership, when two lots adjacent to the synagogue became available in 1955, the congregation was able to purchase both. They constructed a new religious school building in 1956, completing it three months before Beth-El’s 25th anniversary. Edelstein was also a leader in the larger community, serving as mayor from 1975 to 1979.

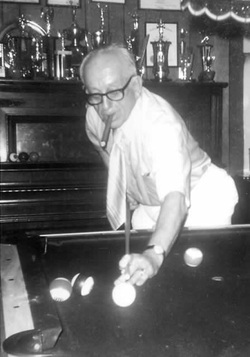

Sam Perl. Photo courtesy of Frances Perl Goodman

Sam Perl. Photo courtesy of Frances Perl Goodman

The Community Grows

The new religious school facility could not have opened at a better time as the Jewish population of Brownsville grew significantly during the post World War II period. While Beth-El’s membership fluctuated in the 1950s, from a high of 52 member families to a low of 35, it grew tremendously in the 1960s, reaching a high of 65 families with 50 children in the religious school. The boom of the 1960s however, paled in comparison to that of the 1970s as, Beth-El reached 100 member families in 1975. An industrial boom in Brownsville and Matamoros, in conjunction with the area’s general economic development, most likely explains the growth of the local Jewish community.

Beth-El’s growth meant that hiring a full-time rabbi was now an attainable goal. However, out of deference to lay-leader Perl, the congregation chose to seek out only a “Director of Education” who also happened to be a rabbi. The congregation soon realized that without affiliating with a specific branch of Judaism, they would be unable to attract a suitable candidate. For its first 40 years, Beth-El, in order to avoid conflict among its diverse congregants, had purposefully avoided formally affiliating with one branch of Judaism. Since affiliation proved to be a prerequisite for hiring an ordained rabbi, Beth-El joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the national organization of Reform Judaism, in 1973. Soon thereafter Rabbi Harry Lawrence became Beth-El’s Director of Education and then official rabbi in the mid-1970s when, amid serious health problems, Sam Perl resigned as lay-leader.

Perl had successfully served as a unifying presence among the diverse congregants, though some of his successors were unable to handle the complicated balance between denominations. When Rabbi Jonathan Gerard, who led the congregation from 1976 to 1979, sought a greater role for women during the prayer service, Orthodox members were upset and even discussed forming a new congregation. This talk of a split petered out due to lack of support, its financially implausibility, and the pacifying actions of Gerard’s successor, Rabbi Mathew Michaels. Despite its sectarian struggles Beth-El celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1981 and in recognition of Beth-El’s longevity Brownsville’s Mayor Emilio Hernandez declared August 31st, 1981 to be “Temple Beth-El Day.”

Even though the congregation had renovated its sanctuary in 1960s, they soon began to discuss building a new synagogue to accommodate their tremendous growth. In 1972, the congregation purchased a plot of land, but resold it due to financial concerns and because the land was deemed unsuitable. A new tract of land was purchased in 1981, though an economic recession delayed the project. Thanks to a 1983 bequest for a new Sunday school from Morris and Mae Rose Weil Stein, in honor of their son Lewis, a former Hebrew school teacher who was killed during World War II, a new synagogue was constructed in 1989.

The new religious school facility could not have opened at a better time as the Jewish population of Brownsville grew significantly during the post World War II period. While Beth-El’s membership fluctuated in the 1950s, from a high of 52 member families to a low of 35, it grew tremendously in the 1960s, reaching a high of 65 families with 50 children in the religious school. The boom of the 1960s however, paled in comparison to that of the 1970s as, Beth-El reached 100 member families in 1975. An industrial boom in Brownsville and Matamoros, in conjunction with the area’s general economic development, most likely explains the growth of the local Jewish community.

Beth-El’s growth meant that hiring a full-time rabbi was now an attainable goal. However, out of deference to lay-leader Perl, the congregation chose to seek out only a “Director of Education” who also happened to be a rabbi. The congregation soon realized that without affiliating with a specific branch of Judaism, they would be unable to attract a suitable candidate. For its first 40 years, Beth-El, in order to avoid conflict among its diverse congregants, had purposefully avoided formally affiliating with one branch of Judaism. Since affiliation proved to be a prerequisite for hiring an ordained rabbi, Beth-El joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the national organization of Reform Judaism, in 1973. Soon thereafter Rabbi Harry Lawrence became Beth-El’s Director of Education and then official rabbi in the mid-1970s when, amid serious health problems, Sam Perl resigned as lay-leader.

Perl had successfully served as a unifying presence among the diverse congregants, though some of his successors were unable to handle the complicated balance between denominations. When Rabbi Jonathan Gerard, who led the congregation from 1976 to 1979, sought a greater role for women during the prayer service, Orthodox members were upset and even discussed forming a new congregation. This talk of a split petered out due to lack of support, its financially implausibility, and the pacifying actions of Gerard’s successor, Rabbi Mathew Michaels. Despite its sectarian struggles Beth-El celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1981 and in recognition of Beth-El’s longevity Brownsville’s Mayor Emilio Hernandez declared August 31st, 1981 to be “Temple Beth-El Day.”

Even though the congregation had renovated its sanctuary in 1960s, they soon began to discuss building a new synagogue to accommodate their tremendous growth. In 1972, the congregation purchased a plot of land, but resold it due to financial concerns and because the land was deemed unsuitable. A new tract of land was purchased in 1981, though an economic recession delayed the project. Thanks to a 1983 bequest for a new Sunday school from Morris and Mae Rose Weil Stein, in honor of their son Lewis, a former Hebrew school teacher who was killed during World War II, a new synagogue was constructed in 1989.

The Jewish Community in Brownsville Today

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

The Jewish community of Brownsville remains strong, though Beth-El’s membership has declined in recent years. As late as 1990 Beth-El had 115 member families, but in 2011, Beth-El reported a membership of only 60 families. While the congregation no longer has an ordained rabbi, it does employ Cantor Henry Greenspan, who leads regular services. This drop in membership is due to an aging congregation as the children raised in Brownsville have largely moved away to bigger cities in Texas and beyond. In addition, a group of Israelis with businesses on nearby Padre Island founded the Orthodox congregation Shova Israel in 2004, which now competes with Beth-El for more traditional members.

In his 1876 letter to the editor of the American Israelite, future Brownsville mayor and then acting-postmaster Benjamin Kowalski reported on the progress of the small Jewish community on the edge of the south Texas frontier. He concluded his letter with the hope that he had “shown the outside world that there is a small spot in Texas called Brownsville where Jews and Judaism still wave.” Through the vicissitudes of almost 170 years of history, Kowalski’s words still ring true today.

In his 1876 letter to the editor of the American Israelite, future Brownsville mayor and then acting-postmaster Benjamin Kowalski reported on the progress of the small Jewish community on the edge of the south Texas frontier. He concluded his letter with the hope that he had “shown the outside world that there is a small spot in Texas called Brownsville where Jews and Judaism still wave.” Through the vicissitudes of almost 170 years of history, Kowalski’s words still ring true today.