Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Corpus Christi, Texas

Corpus Christi: Historical Overview

|

Perhaps it’s ironic that Corpus Christi, which literally means “Body of Christ,” has such a rich Jewish history. Seated on the Gulf of Mexico at the mouth of the Nueces River, the town was founded as Kinney’s Trading Post in 1839, three years after Texas declared independence from Mexico. In addition to its port, Corpus Christi emerged as a significant cattle ranching community by the late 19th century. By the early 20th century, with four railroads serving the area, the town’s population and economy rapidly expanded, drawing immigrants, including Jews, from all over the world.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Corpus Christi

Early Settlers

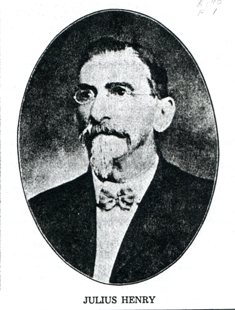

Julius Henry, Corpus Christi’s first Jewish settler, arrived in the area in 1858. Born in Posen, Prussia, in 1839, the sixth of 13 children, Henry decided to emigrate to America to escape the hardships and hunger he faced in Europe. Landing in New York in July of 1854, Henry traveled throughout the country, taking various jobs, including working the salt mines in Pennsylvania, and venturing to Key West, Florida, before settling in Corpus Christi. Here, too, Henry found assorted employment, working as a farmer, a baker, and a shipping clerk. By August 1865, with $500 in savings, he opened his own business, a successful grocery store, which remained in operation for several decades. He sent for and married his cousin, Bertha Nelson, with whom he had seven children.

Another important Jewish settler, Charles Weil, arrived in the United States from Alsace, France, in 1867 at the age of 20. Three years later, he made his way to Corpus Christi, and soon after that, he established the Frank-Weil General Store with his brother-in-law, Emmanuel Frank. They sold goods such as tobacco, jeans, and kerosene, primarily to northern Mexican ranchers. When the Texas-Mexico railroad was built to Laredo, Corpus Christi’s trade with Mexico suffered. As a result, Weil and Frank moved into ranching when, in 1899, Charles bought 40,000 acres of land. His son Jonas was the manager of the ranch and became deeply involved with ranching life. During Texas’ frequent droughts, he took part in a rain making group, sending balloons filled with sulfuric acid and iron shavings into the sky, hoping to produce a downpour, which sometimes worked. He also discovered novel ways to protect his cattle from the fatal Texas fever. Residents remembered Jonas as an expert rancher, always wearing his cowboy boots.

Henry and Weil, along with other early Jewish settlers, were active in the larger Corpus Christi community and regularly interacted with non-Jews. Noted as a “prominent citizen” in the local newspaper, Henry was, among many other positions, elected Alderman of the Second Ward, Grand Senior Warden of the Grand Encampment of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, Grand High Mogul of the Royal Arch Masons, and Postmaster of Corpus Christi. David Hirsch, who operated a dry goods store, was also particularly involved in the city’s civic life, serving as Vice President of the Corpus Christi Fire and Ladder Department, President of the Corpus Christi National Bank, and President of the city’s Independent School His advocacy for free public education for all led to the city posthumously naming an elementary school after him.

By 1875, there were 45 Jews from 11 families living in Corpus Christi. The majority had emigrated from Germany or the Alsace region within the previous five years and earned their livings as merchants – specifically selling dry goods, clothing, and shoes. German-born Morris Lichtenstein established Lichtenstein’s Department Store, which the Corpus Christi Caller Times later called “a focal point of this city for a century.” Moise and Alex Weil, the sons of Charles and the brothers of Jonas, operated a grocery store. Lawrence Levy owned a toy store. Simon Gugenheim, a native Texan who arrived in town in 1882 with just $40, opened Gugenheim and Cohn Dry Goods Store.

Julius Henry, Corpus Christi’s first Jewish settler, arrived in the area in 1858. Born in Posen, Prussia, in 1839, the sixth of 13 children, Henry decided to emigrate to America to escape the hardships and hunger he faced in Europe. Landing in New York in July of 1854, Henry traveled throughout the country, taking various jobs, including working the salt mines in Pennsylvania, and venturing to Key West, Florida, before settling in Corpus Christi. Here, too, Henry found assorted employment, working as a farmer, a baker, and a shipping clerk. By August 1865, with $500 in savings, he opened his own business, a successful grocery store, which remained in operation for several decades. He sent for and married his cousin, Bertha Nelson, with whom he had seven children.

Another important Jewish settler, Charles Weil, arrived in the United States from Alsace, France, in 1867 at the age of 20. Three years later, he made his way to Corpus Christi, and soon after that, he established the Frank-Weil General Store with his brother-in-law, Emmanuel Frank. They sold goods such as tobacco, jeans, and kerosene, primarily to northern Mexican ranchers. When the Texas-Mexico railroad was built to Laredo, Corpus Christi’s trade with Mexico suffered. As a result, Weil and Frank moved into ranching when, in 1899, Charles bought 40,000 acres of land. His son Jonas was the manager of the ranch and became deeply involved with ranching life. During Texas’ frequent droughts, he took part in a rain making group, sending balloons filled with sulfuric acid and iron shavings into the sky, hoping to produce a downpour, which sometimes worked. He also discovered novel ways to protect his cattle from the fatal Texas fever. Residents remembered Jonas as an expert rancher, always wearing his cowboy boots.

Henry and Weil, along with other early Jewish settlers, were active in the larger Corpus Christi community and regularly interacted with non-Jews. Noted as a “prominent citizen” in the local newspaper, Henry was, among many other positions, elected Alderman of the Second Ward, Grand Senior Warden of the Grand Encampment of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, Grand High Mogul of the Royal Arch Masons, and Postmaster of Corpus Christi. David Hirsch, who operated a dry goods store, was also particularly involved in the city’s civic life, serving as Vice President of the Corpus Christi Fire and Ladder Department, President of the Corpus Christi National Bank, and President of the city’s Independent School His advocacy for free public education for all led to the city posthumously naming an elementary school after him.

By 1875, there were 45 Jews from 11 families living in Corpus Christi. The majority had emigrated from Germany or the Alsace region within the previous five years and earned their livings as merchants – specifically selling dry goods, clothing, and shoes. German-born Morris Lichtenstein established Lichtenstein’s Department Store, which the Corpus Christi Caller Times later called “a focal point of this city for a century.” Moise and Alex Weil, the sons of Charles and the brothers of Jonas, operated a grocery store. Lawrence Levy owned a toy store. Simon Gugenheim, a native Texan who arrived in town in 1882 with just $40, opened Gugenheim and Cohn Dry Goods Store.

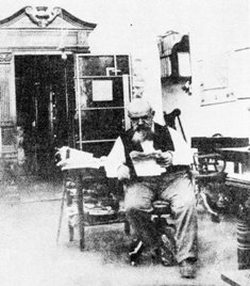

David Hirsch

David Hirsch

Organized Jewish Life in Corpus Christi

In the early years, there were no formal Jewish institutions in town. When David Hirsch’s wife died in 1873, he was forced to transport her body 130 miles to the town of Gonzales just to bury her in a Jewish cemetery. The first effort to start a formal Jewish organization in Corpus Christi is referenced in a June 1875 article in the American Israelite newspaper. It describes the bris of the son of Julius Henry – the fourth ever bris in the city – attended by Henry, Weil, Hirsch and Dr. Aaron Ansell, who performed the ceremony. The anonymous author wrote: “while we were all absorbed in the one absorbing theme of merry-making, a voice – the voice of Benevolence – was heard, demanding attention, attracted by the speaker, we were solicited to unite in the formation of a “Hebrew Benevolent Society.” ‘This,’ he remarked, ‘being the stepping stone to the erection of a temple, in which we would,’ he hoped, ‘at no distant day assemble to do homage to our Redeemer, the One God of Israel.’ The response from fifteen souls was one voice, all vociferated ‘YEA!’”

The Hebrew Benevolent Association, as well as the Hebrew Rest Cemetery, was established that same year. However, it seems that no formal congregation was organized for many years and no regular religious services were held. High Holy Day services took place in homes of Jews or in local buildings, particularly Meuly Hall, and were led by visiting rabbis invited from throughout Texas. According to one 1913 report, Corpus Christi was the home to 100 Jews from 20 families in 1913.

With a steadily growing Jewish population, which reached 200 in 1927, a congregation was finally organized on September 30, 1928. Ed Grossman was elected the first president of the congregation. Two days later, the land for its synagogue, Temple Beth El, was purchased for $875 at the corner of 11th and Craig Streets. In the spring of 1930, construction commenced on the one-room wooden building, which was being used by the following year. In 1932, Beth El officially organized, adopting a constitution which formally declared that the congregation would be Reform. Those who wanted to adhere to a more traditional ritual by wearing yarmulkes and tallit were free to do so. A group of Orthodox members decided to hold their own separate High Holiday services at private homes and later Meuly Hall.

In the early years, there were no formal Jewish institutions in town. When David Hirsch’s wife died in 1873, he was forced to transport her body 130 miles to the town of Gonzales just to bury her in a Jewish cemetery. The first effort to start a formal Jewish organization in Corpus Christi is referenced in a June 1875 article in the American Israelite newspaper. It describes the bris of the son of Julius Henry – the fourth ever bris in the city – attended by Henry, Weil, Hirsch and Dr. Aaron Ansell, who performed the ceremony. The anonymous author wrote: “while we were all absorbed in the one absorbing theme of merry-making, a voice – the voice of Benevolence – was heard, demanding attention, attracted by the speaker, we were solicited to unite in the formation of a “Hebrew Benevolent Society.” ‘This,’ he remarked, ‘being the stepping stone to the erection of a temple, in which we would,’ he hoped, ‘at no distant day assemble to do homage to our Redeemer, the One God of Israel.’ The response from fifteen souls was one voice, all vociferated ‘YEA!’”

The Hebrew Benevolent Association, as well as the Hebrew Rest Cemetery, was established that same year. However, it seems that no formal congregation was organized for many years and no regular religious services were held. High Holy Day services took place in homes of Jews or in local buildings, particularly Meuly Hall, and were led by visiting rabbis invited from throughout Texas. According to one 1913 report, Corpus Christi was the home to 100 Jews from 20 families in 1913.

With a steadily growing Jewish population, which reached 200 in 1927, a congregation was finally organized on September 30, 1928. Ed Grossman was elected the first president of the congregation. Two days later, the land for its synagogue, Temple Beth El, was purchased for $875 at the corner of 11th and Craig Streets. In the spring of 1930, construction commenced on the one-room wooden building, which was being used by the following year. In 1932, Beth El officially organized, adopting a constitution which formally declared that the congregation would be Reform. Those who wanted to adhere to a more traditional ritual by wearing yarmulkes and tallit were free to do so. A group of Orthodox members decided to hold their own separate High Holiday services at private homes and later Meuly Hall.

Rabbi Sidney Wolf

Rabbi Sidney Wolf

Beth El soon moved to hire a full-time rabbi, the first in Corpus Christi. Per a recommendation by the Hebrew Union College, Rabbi Sidney Wolf was hired for a three-month trial, arriving ten days before Rosh Hashanah in 1932. One month later, Rabbi Wolf was given a one-year contract, and in November, he was formally installed by Rabbi Henry Cohen of Galveston. By the end of Rabbi Wolf’s first year at Temple Beth El, membership totaled 60 families. Corpus Christi Jews had held informal religious schools as early as 1916 when Jeannie Gunst taught the community’s children in her home, but in 1930 Beth El established a formal religious school with 11 children. By the time the synagogue was completed, the school had grown to 18 students. Soon after Rabbi Wolf’s arrival, the number of students increased to 40 children.

As Corpus Christi’s general population grew, especially with the discovery of oil nearby and the establishment of the city’s deep water port in 1926, the Jewish community grew as well. By 1937, an estimated 645 Jews lived in Corpus Christi. Due to this growth, Beth El President Alex Weil proposed building a new synagogue in 1936. That fall, the wooden building was demolished and construction for the new temple began. Services took place in a downtown dance studio until the new synagogue was dedicated on April 5, 1937. While the congregation had been Reform in practice since its founding, it did not formally affiliate with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations until 1946.

As Corpus Christi’s general population grew, especially with the discovery of oil nearby and the establishment of the city’s deep water port in 1926, the Jewish community grew as well. By 1937, an estimated 645 Jews lived in Corpus Christi. Due to this growth, Beth El President Alex Weil proposed building a new synagogue in 1936. That fall, the wooden building was demolished and construction for the new temple began. Services took place in a downtown dance studio until the new synagogue was dedicated on April 5, 1937. While the congregation had been Reform in practice since its founding, it did not formally affiliate with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations until 1946.

Beth El's synagogue, dedicated in 1937

Beth El's synagogue, dedicated in 1937

The Community Grows

Due to the oil boom and bustling port, Corpus Christi’s population doubled between 1931 and 1941. In addition, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1940 appropriation of $25,000,000 to build the Naval Air Station at Corpus Christi, energized the economy, employing more than 9,000 workers in 1941. As a result, a new wave of Jews arrived in the city, many of whom came from Orthodox backgrounds.

In October 1942, the city’s growing number of Orthodox Jews banded together to form “Shomre Emunah” meaning “keepers of the faith.” The following year, the group established a formal congregation, under the leadership of President Will Rauch, which was called B’nai Israel. The new congregation celebrated its first High Holiday services in 1943, led by their newly hired full-time rabbi, Yonah Geller. The next year B’nai Israel moved into its own space on Elizabeth and 13th Streets. In September 1950, the congregation once again moved, this time to Fort Worth Street. Though differing in religious practices, B’nai Israel and Beth El had a long tradition of cooperation. Prior to B’nai Israel’s construction, Beth El had allowed its sister congregation to use its annex for services. For numerous years, the two congregations organized a joint Simchat Torah celebration. In 1952, the two congregations established the Jewish Community Council, unifying youth activities and other social functions.

Due to the oil boom and bustling port, Corpus Christi’s population doubled between 1931 and 1941. In addition, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1940 appropriation of $25,000,000 to build the Naval Air Station at Corpus Christi, energized the economy, employing more than 9,000 workers in 1941. As a result, a new wave of Jews arrived in the city, many of whom came from Orthodox backgrounds.

In October 1942, the city’s growing number of Orthodox Jews banded together to form “Shomre Emunah” meaning “keepers of the faith.” The following year, the group established a formal congregation, under the leadership of President Will Rauch, which was called B’nai Israel. The new congregation celebrated its first High Holiday services in 1943, led by their newly hired full-time rabbi, Yonah Geller. The next year B’nai Israel moved into its own space on Elizabeth and 13th Streets. In September 1950, the congregation once again moved, this time to Fort Worth Street. Though differing in religious practices, B’nai Israel and Beth El had a long tradition of cooperation. Prior to B’nai Israel’s construction, Beth El had allowed its sister congregation to use its annex for services. For numerous years, the two congregations organized a joint Simchat Torah celebration. In 1952, the two congregations established the Jewish Community Council, unifying youth activities and other social functions.

Rabbi Yonah Geller of B'nai Israel

Rabbi Yonah Geller of B'nai Israel

Jewish Charitable Efforts

The Corpus Christi Jewish community became especially involved in welfare and charity. Their war effort was particularly notable. Stimulated by the horrific events occurring in Europe, the city’s Jewish Welfare Fund, under the presidency of Alex Weil, raised $16,000 in 1939 alone. Beth El organized an Army and Navy Committee that catered to the nearby Naval Air Station, providing meals and arranging social functions for those stationed there. Corpus Christi’s Jewish women placed second in the county, selling $226,000 in war bonds, and Jewish families provided free long distance phone calls to servicemen. In 1946, the Jewish Welfare Fund raised $126,611, spurred by Mayor Robert T. Wilson’s moving $5,000 donation in memory of his late son, who had died fighting in Europe.

Perhaps the Jewish community was so involved in the war effort because of the great representation of Jewish servicemen from Corpus Christi. While only 0.5 percent of the city’s population was Jewish, about 10 percent of those who were enlisted or drafted from Corpus Christi during World War II were Jews. With the help of the Jewish Welfare Fund, between 1940 and 1957, 13 Holocaust refugee families and individuals settled in Corpus Christi.

Besides the war effort, the Jews of Corpus Christi established numerous other organizations to help Jews and non-Jews alike. The Hebrew Free Loan Society was chartered in 1940 with Abe Block as President. With 200 members paying annual $3 dues, the organization was able to provide emergency financial support – up to $200 – to those in need with no interest charged. The Council of Jewish Women, organized in 1947 with 35 members, undertook many charitable projects as well. They established a library at the Cuddihy Home for Girls, while also arranging birthday parties and providing clothes. Outside the United States, the Council sponsored a medical school in Paris and sent supplies to a Moroccan nursery school. The group even brought former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt as a lecturer in 1955. In addition, Zionist organizations, including Hadassah, Young Judea, and Pioneer Women, were particularly active in Corpus Christi, sponsoring guest speakers, raising money, and supporting the establishment of the state of Israel.

The Corpus Christi Jewish community became especially involved in welfare and charity. Their war effort was particularly notable. Stimulated by the horrific events occurring in Europe, the city’s Jewish Welfare Fund, under the presidency of Alex Weil, raised $16,000 in 1939 alone. Beth El organized an Army and Navy Committee that catered to the nearby Naval Air Station, providing meals and arranging social functions for those stationed there. Corpus Christi’s Jewish women placed second in the county, selling $226,000 in war bonds, and Jewish families provided free long distance phone calls to servicemen. In 1946, the Jewish Welfare Fund raised $126,611, spurred by Mayor Robert T. Wilson’s moving $5,000 donation in memory of his late son, who had died fighting in Europe.

Perhaps the Jewish community was so involved in the war effort because of the great representation of Jewish servicemen from Corpus Christi. While only 0.5 percent of the city’s population was Jewish, about 10 percent of those who were enlisted or drafted from Corpus Christi during World War II were Jews. With the help of the Jewish Welfare Fund, between 1940 and 1957, 13 Holocaust refugee families and individuals settled in Corpus Christi.

Besides the war effort, the Jews of Corpus Christi established numerous other organizations to help Jews and non-Jews alike. The Hebrew Free Loan Society was chartered in 1940 with Abe Block as President. With 200 members paying annual $3 dues, the organization was able to provide emergency financial support – up to $200 – to those in need with no interest charged. The Council of Jewish Women, organized in 1947 with 35 members, undertook many charitable projects as well. They established a library at the Cuddihy Home for Girls, while also arranging birthday parties and providing clothes. Outside the United States, the Council sponsored a medical school in Paris and sent supplies to a Moroccan nursery school. The group even brought former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt as a lecturer in 1955. In addition, Zionist organizations, including Hadassah, Young Judea, and Pioneer Women, were particularly active in Corpus Christi, sponsoring guest speakers, raising money, and supporting the establishment of the state of Israel.

Fanny Alexander

Fanny Alexander

Civic Engagement

Corpus Christi’s Jews were also greatly involved in civic life. Fanny Alexander, for example, took positions in many local charities, including serving as President of the Nueces County Chapter of the American Red Cross, Nueces County Tuberculosis Association, Board of the Hilltop Sanitarium, and of the Texas Branch of the American Association of University Women. Lester Gunst served as Postmaster of Corpus Christi, appointed by President Herbert Hoover. The local Junior Chamber of Commerce named Nat Selinger Corpus Christi’s “Outstanding Man” for his many contributions to the city. Albert Lichtenstein, the grandson of Lichtenstein’s Department Store founder Morris, was Corpus Christi’s first Jewish mayor, elected in 1953.

Corpus Christi’s Jews were also greatly involved in civic life. Fanny Alexander, for example, took positions in many local charities, including serving as President of the Nueces County Chapter of the American Red Cross, Nueces County Tuberculosis Association, Board of the Hilltop Sanitarium, and of the Texas Branch of the American Association of University Women. Lester Gunst served as Postmaster of Corpus Christi, appointed by President Herbert Hoover. The local Junior Chamber of Commerce named Nat Selinger Corpus Christi’s “Outstanding Man” for his many contributions to the city. Albert Lichtenstein, the grandson of Lichtenstein’s Department Store founder Morris, was Corpus Christi’s first Jewish mayor, elected in 1953.

After World War II

There is likely no greater rags to riches story than that of Sam Kane. A former Czech Resistance fighter, Kane left Europe after most of his family had been killed in the Holocaust. He opened a butcher shop in Corpus Christi after the war. Though inexperienced in the trade, he learned to cut beef with the help of his suppliers. He didn’t speak English initially, but became fluent through interactions with his customers. Kane soon moved from selling beef to producing it. Established in 1949, Sam Kane Beef Processors, Inc. became a tremendous success. Still in operation today, the firm is the seventh largest meatpacking company in the world, employing 800 workers in Corpus Christi.

After World War II, the city continued to grow, becoming the 12th largest port in the country and almost doubling its population by the end of the 1940s. By the time of Temple Beth El’s 15th anniversary in 1947, it had 187 families, 85 children in its religious school, and 130 sisterhood members. The next year, with only five classrooms for its school, the congregation purchased property behind the synagogue to accommodate its growth, and in 1950, it added six classrooms, an auditorium, a new kitchen, a library, and administrative offices. In 1968, the congregation voted to buy property on Saratoga Boulevard and Shea Parkway for a new synagogue. However, due to lingering questions about financing the move and the search for a new rabbi, construction did not begin until 1983.

Rabbi Wolf continued to serve Temple Beth El until his retirement in 1972. Wolf was known for his close ties to the non-Jewish community. In 1950, he started the tradition of inviting African American ministers to preach at Temple Beth El in honor of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, known as Race Relations Day. Wolf supported an African American Boy Scout troop, helping to purchase their uniforms. He took his students on yearly tours of a local African American church, and was a driving force in an effort to desegregate the city’s golf course. He organized a joint Thanksgiving service with a local Episcopal congregation in 1936, an event so rare at the time that Time Magazine devoted an article to it. Rabbi Wolf was also involved in many civic organizations, ranging from his time as President of the American Red Cross in 1937 to helping Mexican-Americans read and write at the Adult Learning Center in the 1970s. His impact was so strong in Corpus Christi that November 10, 1982 was proclaimed Rabbi Sidney Wolf Day.

There is likely no greater rags to riches story than that of Sam Kane. A former Czech Resistance fighter, Kane left Europe after most of his family had been killed in the Holocaust. He opened a butcher shop in Corpus Christi after the war. Though inexperienced in the trade, he learned to cut beef with the help of his suppliers. He didn’t speak English initially, but became fluent through interactions with his customers. Kane soon moved from selling beef to producing it. Established in 1949, Sam Kane Beef Processors, Inc. became a tremendous success. Still in operation today, the firm is the seventh largest meatpacking company in the world, employing 800 workers in Corpus Christi.

After World War II, the city continued to grow, becoming the 12th largest port in the country and almost doubling its population by the end of the 1940s. By the time of Temple Beth El’s 15th anniversary in 1947, it had 187 families, 85 children in its religious school, and 130 sisterhood members. The next year, with only five classrooms for its school, the congregation purchased property behind the synagogue to accommodate its growth, and in 1950, it added six classrooms, an auditorium, a new kitchen, a library, and administrative offices. In 1968, the congregation voted to buy property on Saratoga Boulevard and Shea Parkway for a new synagogue. However, due to lingering questions about financing the move and the search for a new rabbi, construction did not begin until 1983.

Rabbi Wolf continued to serve Temple Beth El until his retirement in 1972. Wolf was known for his close ties to the non-Jewish community. In 1950, he started the tradition of inviting African American ministers to preach at Temple Beth El in honor of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, known as Race Relations Day. Wolf supported an African American Boy Scout troop, helping to purchase their uniforms. He took his students on yearly tours of a local African American church, and was a driving force in an effort to desegregate the city’s golf course. He organized a joint Thanksgiving service with a local Episcopal congregation in 1936, an event so rare at the time that Time Magazine devoted an article to it. Rabbi Wolf was also involved in many civic organizations, ranging from his time as President of the American Red Cross in 1937 to helping Mexican-Americans read and write at the Adult Learning Center in the 1970s. His impact was so strong in Corpus Christi that November 10, 1982 was proclaimed Rabbi Sidney Wolf Day.

The Jewish Community in Corpus Christi Today

The Jewish population in Corpus Christi reached its peak in 1990 at about 1,400, and has since declined. With both congregations shrinking, the Reform Beth El and the now Conservative B’nai Israel decided to merge, forming Congregation Beth Israel in 2005. With just about 400 Jewish families, 1,200 Jews in total, many leaders felt it was unnecessary to keep two separate synagogues afloat. Despite opposition from members of both congregations, and after committees, consultants and regulations were set up, a vast majority voted to approve the merger. Subsequently, B’nai Israel’s building was sold, its members absorbed into the Beth El congregation. Orthodox Jews and those unhappy with the merger have formed their own small havurot. As the older generation ages and the younger generation moves away to larger cities, the Corpus Christi Jewish community has helped ensure its future vitality thanks to this union.

Sources

Wolf, Rabbi Sidney and Wilk, Helen K., Our Golden Years: A History of Temple Beth El.