Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - El Paso, Texas

Historical Overview

Stories of the Jewish Community in El Paso

Olga Kohlberg

Olga Kohlberg

Early Settlers

The first Jews were drawn to El Paso as it became a center for international trade. Brothers Samuel and Joseph Schutz were among the first Jews in the area. Samuel came first, arriving in 1856 and opening a grocery business; his brother soon followed. Ernest Angerstein settled south of the river in Mexico, opening a general store. Although El Paso was situated in the far west corner of the westernmost Southern state, secession and the Civil War unsettled the small town. The Schutz brothers opposed secession, while Angerstein ended up siding with whichever army was in charge of the area. When Confederate soldiers controlled El Paso, Angerstein claimed to support the South’s cause. Once the Union forces took charge, Angerstein expressed support for the U.S. When Angerstein got a U.S. Army contract to provide corn for the troops, his competitors complained that he was pro-Confederate. The army’s Inspector General studied the charges and concluded that Angerstein, as a foreigner pursuing his own financial interest, was simply trying to avoid being involved on either side of the conflict.

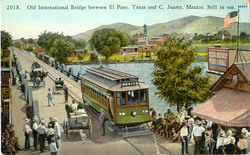

After the war, this handful of Jewish merchants prospered. In 1872, Angerstein was appointed post trader for Fort Bliss, even though he technically lived just across the river in Mexico. Samuel Schutz, who was worth about $2000 in 1860, had become a wealthy businessman by 1870, with about $80,000 in real and personal estate. He and his brother opened a flour mill after the war to supplement their grocery business. Angerstein also had diverse economic interests, owning a mining operation and a plantation in addition to his retail business. Ernest Kohlberg came to El Paso in 1875, working for the Schutz brother initially. Kohlberg ran a branch store for the Shutz Brothers across the border in Juarez before opening his own cigar store in El Paso in 1881. Five years later, Kohlberg opened a cigar factory in the city, which remained in operation until 1924.El Paso was transformed once it was linked to the rest of the country via rail in 1881. As it became a major center for trade, El Paso grew tremendously in the last two decades of the 19th century, increasing from 500 residents in 1880 to almost 16,000 in 1900. Not surprisingly, its Jewish community grew as well. Not long after the town was incorporated in 1873, Jews moved into positions of civic leadership in El Paso. Joseph Schutz served as an alderman by 1873, while Samuel Schutz was elected mayor in 1880. Ernest Kohlberg became a leader of the El Paso business community, helping to construct the city’s first power plant and serving as a founding director of the Rio Grande Valley Bank and Trust Company. Kohlberg was also elected a city alderman. His wife Olga was also very involved with various causes in El Paso. In 1892, she helped start the city’s first kindergarten, and helped found the El Paso Public Library in 1895. She served as head of the public library board from 1904 until she died in 1936. Olga Kohlberg was also instrumental in building the city’s first charity hospital.

The first Jews were drawn to El Paso as it became a center for international trade. Brothers Samuel and Joseph Schutz were among the first Jews in the area. Samuel came first, arriving in 1856 and opening a grocery business; his brother soon followed. Ernest Angerstein settled south of the river in Mexico, opening a general store. Although El Paso was situated in the far west corner of the westernmost Southern state, secession and the Civil War unsettled the small town. The Schutz brothers opposed secession, while Angerstein ended up siding with whichever army was in charge of the area. When Confederate soldiers controlled El Paso, Angerstein claimed to support the South’s cause. Once the Union forces took charge, Angerstein expressed support for the U.S. When Angerstein got a U.S. Army contract to provide corn for the troops, his competitors complained that he was pro-Confederate. The army’s Inspector General studied the charges and concluded that Angerstein, as a foreigner pursuing his own financial interest, was simply trying to avoid being involved on either side of the conflict.

After the war, this handful of Jewish merchants prospered. In 1872, Angerstein was appointed post trader for Fort Bliss, even though he technically lived just across the river in Mexico. Samuel Schutz, who was worth about $2000 in 1860, had become a wealthy businessman by 1870, with about $80,000 in real and personal estate. He and his brother opened a flour mill after the war to supplement their grocery business. Angerstein also had diverse economic interests, owning a mining operation and a plantation in addition to his retail business. Ernest Kohlberg came to El Paso in 1875, working for the Schutz brother initially. Kohlberg ran a branch store for the Shutz Brothers across the border in Juarez before opening his own cigar store in El Paso in 1881. Five years later, Kohlberg opened a cigar factory in the city, which remained in operation until 1924.El Paso was transformed once it was linked to the rest of the country via rail in 1881. As it became a major center for trade, El Paso grew tremendously in the last two decades of the 19th century, increasing from 500 residents in 1880 to almost 16,000 in 1900. Not surprisingly, its Jewish community grew as well. Not long after the town was incorporated in 1873, Jews moved into positions of civic leadership in El Paso. Joseph Schutz served as an alderman by 1873, while Samuel Schutz was elected mayor in 1880. Ernest Kohlberg became a leader of the El Paso business community, helping to construct the city’s first power plant and serving as a founding director of the Rio Grande Valley Bank and Trust Company. Kohlberg was also elected a city alderman. His wife Olga was also very involved with various causes in El Paso. In 1892, she helped start the city’s first kindergarten, and helped found the El Paso Public Library in 1895. She served as head of the public library board from 1904 until she died in 1936. Olga Kohlberg was also instrumental in building the city’s first charity hospital.

Adolph Solomon

Adolph Solomon

Kohlberg and Schutz were not the only Jewish officeholders in El Paso during this period. Indeed, the number of Jewish elected officials during the early years of El Paso is remarkable. Born in Prussia, Adolph Solomon moved to El Paso from Arizona in 1887. Soon after arriving in Texas and opening a general merchandise store, Solomon served as an alderman. In 1894, he was elected mayor of El Paso. Samuel Freudenthal came to El Paso in 1885, and was elected alderman in 1887. He later served several terms on the local school board. In 1902, he was elected to his first of several terms as a county commissioner. Owner of a wholesale grocery firm, Freudenthal was approached by local political leaders to run for office since he was a strong representative of the local business community. Freudenthal became the first president of the El Paso Chamber of Commerce in the early 1900s. While these Jews were able to win elected office soon after arriving, sometimes, it was too soon. Adolph Krakauer, a Bavarian native, came to the United States in 1865. He settled in El Paso in the 1870s, opening a mining and hardware business with two partners. In 1899, Krakauer was elected mayor of El Paso as a Republican, but his victory was overturned when it was discovered that he had not yet completed the naturalization process and become a U.S. citizen. Although he never actually held the office, Krakauer’s election further highlights the important role Jewish merchants played in the early political and economic development of El Paso.

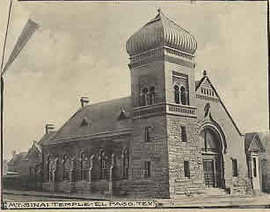

Mt. Sinai's first temple.

Mt. Sinai's first temple. Photo courtesy of Hollace Weiner.

Organized Jewish Life in El Paso

As El Paso’s Jewish community grew in the 1880s, it slowly began to organize. After a Jewish woman died in 1884, El Paso Jews bought land for a cemetery. In 1887, they established the Mt. Sinai Association to oversee the cemetery and to care for Jews in need. Isaac Haas was the first president of the organization, which had 31 members. In 1889, 19 local women founded the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society, which aided Jewish women and families. In 1890, it created a Sunday school, led by Ada Calisher, that met at the county courthouse. The Mt. Sinai Association was not a congregation per se, but over time it began to serve many of the same functions. For the High Holidays, the association would hold worship services with lay leaders. During these early years, the group met at the county courthouse and a Presbyterian Church. In 1893, they brought in a student rabbi from Hebrew Union College to lead High Holiday services, which were held at the Odd Fellows Hall. By 1897, the association had 53 members, a few of whom lived in small towns in New Mexico.

In 1898, Rabbi Oscar Cohen of Mobile, Alabama was visiting El Paso to recuperate from health problems. He encouraged the Mt. Sinai Association to become a formal congregation, hold weekly services, and build a permanent synagogue. With Rabbi Cohen’s prodding, El Paso Jews established Temple Mt. Sinai, which took over responsibility for the Jewish cemetery. The congregation, led by its first president Adolph Solomon, hired Rabbi Cohen as its full-time spiritual leader. Of the 23 men who attended the congregation’s founding meeting, 83% were immigrants. The large majority of them came from Germany, though 21% of the foreign born members came from Russia or Hungary. Although most members were immigrants, they had been in the U.S. for a while; their average year of immigration was 1877. A majority of the founding members, 61%, were merchants, while 22% were store clerks or traveling salesmen. One railroad watchman was the only blue collar worker among the founding members. Most of them were middle-aged, as their average age was 40. Less than half, 43%, owned their own homes, which indicates that many of these early members were still getting established economically.While Temple Mt. Sinai initially held services at Chopin Hall and the Presbyterian Church, in 1899 the congregation built a synagogue at the corner of Oregon and Idaho Streets. Local Christians donated about $1600 of the $6000 cost for the building while three Christian ministers took part in the dedication ceremony. Such support was a testament to the close relations between the Jewish and Christian communities in El Paso. By 1900, Mt. Sinai had 80 members, 32 children in its religious school, and $3000 in annual income. The previous year, women of the congregation founded the Ladies Temple Aid Society, which raised money for Mt. Sinai and its religious school through concerts, balls, and bazaars. One successful affair in 1906 raised $1200, which was used to pay off the remaining debt on the temple building.

As El Paso’s Jewish community grew in the 1880s, it slowly began to organize. After a Jewish woman died in 1884, El Paso Jews bought land for a cemetery. In 1887, they established the Mt. Sinai Association to oversee the cemetery and to care for Jews in need. Isaac Haas was the first president of the organization, which had 31 members. In 1889, 19 local women founded the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society, which aided Jewish women and families. In 1890, it created a Sunday school, led by Ada Calisher, that met at the county courthouse. The Mt. Sinai Association was not a congregation per se, but over time it began to serve many of the same functions. For the High Holidays, the association would hold worship services with lay leaders. During these early years, the group met at the county courthouse and a Presbyterian Church. In 1893, they brought in a student rabbi from Hebrew Union College to lead High Holiday services, which were held at the Odd Fellows Hall. By 1897, the association had 53 members, a few of whom lived in small towns in New Mexico.

In 1898, Rabbi Oscar Cohen of Mobile, Alabama was visiting El Paso to recuperate from health problems. He encouraged the Mt. Sinai Association to become a formal congregation, hold weekly services, and build a permanent synagogue. With Rabbi Cohen’s prodding, El Paso Jews established Temple Mt. Sinai, which took over responsibility for the Jewish cemetery. The congregation, led by its first president Adolph Solomon, hired Rabbi Cohen as its full-time spiritual leader. Of the 23 men who attended the congregation’s founding meeting, 83% were immigrants. The large majority of them came from Germany, though 21% of the foreign born members came from Russia or Hungary. Although most members were immigrants, they had been in the U.S. for a while; their average year of immigration was 1877. A majority of the founding members, 61%, were merchants, while 22% were store clerks or traveling salesmen. One railroad watchman was the only blue collar worker among the founding members. Most of them were middle-aged, as their average age was 40. Less than half, 43%, owned their own homes, which indicates that many of these early members were still getting established economically.While Temple Mt. Sinai initially held services at Chopin Hall and the Presbyterian Church, in 1899 the congregation built a synagogue at the corner of Oregon and Idaho Streets. Local Christians donated about $1600 of the $6000 cost for the building while three Christian ministers took part in the dedication ceremony. Such support was a testament to the close relations between the Jewish and Christian communities in El Paso. By 1900, Mt. Sinai had 80 members, 32 children in its religious school, and $3000 in annual income. The previous year, women of the congregation founded the Ladies Temple Aid Society, which raised money for Mt. Sinai and its religious school through concerts, balls, and bazaars. One successful affair in 1906 raised $1200, which was used to pay off the remaining debt on the temple building.

Mt. Sinai basketball team with Rabbi Zielonka.

Mt. Sinai basketball team with Rabbi Zielonka. Photo courtesy of Hollace Weiner.

When Rabbi Cohen left for Dallas in 1900, Mt. Sinai hired Rabbi Martin Zielonka to replace him. Born in Berlin in 1877, Zielonka came to the U.S. with his family when he was just four years old. Trained at Hebrew Union College, Zielonka tried to convince Mt. Sinai to join the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1902. Although the congregation had been Reform in ritual from its founding, they chose not to affiliate with the UAHC for financial reasons in 1902. Finally, in 1906, Mt. Sinai became an official Reform congregation by joining the UAHC. Zielonka went on to become very involved civically in El Paso, establishing several local charities, including a tuberculosis clinic.

By 1910, Mt. Sinai had 114 members and soon outgrew its modest temple. In 1914, they bought land for a new larger synagogue. Their new red brick temple, dedicated in 1916, cost $50,000, and featured a sanctuary that could seat 750 people, along with beautiful stained glass windows. The new temple also had a theatrical stage, social hall, billiard room, as well as a basement gymnasium. Mt. Sinai had a youth basketball team that played in a local church league, wearing uniforms emblazoned with a Star of David on the front. By 1920, Mt. Sinai had 140 member families and 164 children in its religious school

By 1910, Mt. Sinai had 114 members and soon outgrew its modest temple. In 1914, they bought land for a new larger synagogue. Their new red brick temple, dedicated in 1916, cost $50,000, and featured a sanctuary that could seat 750 people, along with beautiful stained glass windows. The new temple also had a theatrical stage, social hall, billiard room, as well as a basement gymnasium. Mt. Sinai had a youth basketball team that played in a local church league, wearing uniforms emblazoned with a Star of David on the front. By 1920, Mt. Sinai had 140 member families and 164 children in its religious school

B'nai Zion's "synagogue center"

B'nai Zion's "synagogue center"

Not all El Paso Jews wanted to join a Reform congregation. By the late 1890s, a growing number of Orthodox Jews, mostly immigrants from Eastern Europe, had begun to meet together informally for yahrzeits and the High Holidays. In 1900, the group founded B’nai Zion congregation and soon bought land for their own Orthodox cemetery. In 1903, B’nai Zion was officially chartered and hired Nathan Schechter to be their cantor and shochet (kosher butcher). During the congregation’s first decade, its members met in private homes and rented rooms. By 1910, with 65 members, B’nai Zion finally bought land for a synagogue, which was dedicated two years later. The modest synagogue cost $6000 and included a balcony for female worshipers. Despite this progress, there was dissension within the Orthodox community. In 1912, a group split off from B’nai Zion and founded Congregation Achim Ne’emonim. This breakaway group remained small and never built its own synagogue. In 1920, the members of Achim Ne’emonim rejoined B’nai Zion.

Once the El Paso Jewish community was reunified, B’nai Zion expanded, creating a chevra kadisha, Talmud Torah, Free Loan Society, and a Jewish youth group all in the early 1920s. They also hired their first ordained rabbi, Charles Blumenthal, who led the congregation from 1921 to 1923. Perhaps a product of the reunion with Achim Ne’emonim, the congregation introduced a compromise seating arrangement in its sanctuary in 1920. The first six rows of the center section would be reserved for men only, while men and women could sit together in the remaining rows. The left section of the sanctuary would continue to enforce separate seating for men and women.

B’nai Zion continued its movement away from strict Orthodoxy when it hired Rabbi Joseph Roth, a graduate from the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary, in 1923. The congregation flourished under Rabbi Roth’s leadership, growing from 130 members in 1923 to 200 in 1925. They quickly outgrew their synagogue and were already raising money for a new one by 1921. This new synagogue would be shaped by the “synagogue center” trend and was designed “to keep our young loyal to our Jewish traditions by meeting their religious, intellectual, and social needs in a modern and up-to-date manner,” according to a history of the congregation written in 1927. The new building, which cost $160,000, featured a large sanctuary that could seat 575 and a smaller chapel that could hold 250. It also had an auditorium and a gymnasium with showers, a ballroom with a stage, club and billiard rooms, and even space for bowling alleys. The education wing was called the Jewish Community Center, and was designed to serve the entire El Paso Jewish community. Haymon Krupp, who also belonged to Mt. Sinai, gave the money for the new sanctuary. Joe Goodman was a longtime leader of the congregation, and was named honorary president for life in 1927. After Goodman died in 1958, a chapel at B’nai Zion was named in his honor.

Once the El Paso Jewish community was reunified, B’nai Zion expanded, creating a chevra kadisha, Talmud Torah, Free Loan Society, and a Jewish youth group all in the early 1920s. They also hired their first ordained rabbi, Charles Blumenthal, who led the congregation from 1921 to 1923. Perhaps a product of the reunion with Achim Ne’emonim, the congregation introduced a compromise seating arrangement in its sanctuary in 1920. The first six rows of the center section would be reserved for men only, while men and women could sit together in the remaining rows. The left section of the sanctuary would continue to enforce separate seating for men and women.

B’nai Zion continued its movement away from strict Orthodoxy when it hired Rabbi Joseph Roth, a graduate from the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary, in 1923. The congregation flourished under Rabbi Roth’s leadership, growing from 130 members in 1923 to 200 in 1925. They quickly outgrew their synagogue and were already raising money for a new one by 1921. This new synagogue would be shaped by the “synagogue center” trend and was designed “to keep our young loyal to our Jewish traditions by meeting their religious, intellectual, and social needs in a modern and up-to-date manner,” according to a history of the congregation written in 1927. The new building, which cost $160,000, featured a large sanctuary that could seat 575 and a smaller chapel that could hold 250. It also had an auditorium and a gymnasium with showers, a ballroom with a stage, club and billiard rooms, and even space for bowling alleys. The education wing was called the Jewish Community Center, and was designed to serve the entire El Paso Jewish community. Haymon Krupp, who also belonged to Mt. Sinai, gave the money for the new sanctuary. Joe Goodman was a longtime leader of the congregation, and was named honorary president for life in 1927. After Goodman died in 1958, a chapel at B’nai Zion was named in his honor.

Popular Dry Goods Company

Popular Dry Goods Company

The Early 20th Century

The development of El Paso’s two Jewish congregations mirrored that of the city itself. After the railroad boom, El Paso became a wild west frontier trading center, with plenty of saloons and gambling dens. In 1905, the city, seeking to improve its reputation, closed the brothels and gambling houses. By 1910, 39,000 people lived in El Paso. One of those who came to El Paso seeking fortune was Haymon Krupp, who moved to the city in 1890, working for his brother’s dry good store initially. In the early 1900s, Krupp opened his own wholesale and retail dry goods business. In 1916, he opened a clothing manufacturing business, which made men’s work clothes and women’s dresses, employing 500 workers at its peak. Krupp is perhaps best remembered for his forays into the oil business. Krupp, along with his partner, leased the drilling rights to arid west Texas land owned by the University of Texas. After a few years of frustration, their well Santa Rita #1 finally struck oil in 1923. The profits from this and subsequent wells enriched Krupp and the University of Texas, help making it into a world class institution. The Santa Rita well was later put on display at the UT-Austin campus to commemorate its impact on the university. Krupp was a generous donor to both El Paso congregations and gave free coal to the poor on Christmas for forty years. Unfortunately, Krupp lost much of his fortune when later oil ventures failed.

The development of El Paso’s two Jewish congregations mirrored that of the city itself. After the railroad boom, El Paso became a wild west frontier trading center, with plenty of saloons and gambling dens. In 1905, the city, seeking to improve its reputation, closed the brothels and gambling houses. By 1910, 39,000 people lived in El Paso. One of those who came to El Paso seeking fortune was Haymon Krupp, who moved to the city in 1890, working for his brother’s dry good store initially. In the early 1900s, Krupp opened his own wholesale and retail dry goods business. In 1916, he opened a clothing manufacturing business, which made men’s work clothes and women’s dresses, employing 500 workers at its peak. Krupp is perhaps best remembered for his forays into the oil business. Krupp, along with his partner, leased the drilling rights to arid west Texas land owned by the University of Texas. After a few years of frustration, their well Santa Rita #1 finally struck oil in 1923. The profits from this and subsequent wells enriched Krupp and the University of Texas, help making it into a world class institution. The Santa Rita well was later put on display at the UT-Austin campus to commemorate its impact on the university. Krupp was a generous donor to both El Paso congregations and gave free coal to the poor on Christmas for forty years. Unfortunately, Krupp lost much of his fortune when later oil ventures failed.

Haymon Krupp

Haymon Krupp

Because of its proximity to the border, El Paso has always been closely tied to Mexico economically and culturally. The Mexican Revolution had a big impact on the city, especially when the United States sent 50,000 troops to Fort Bliss to protect the border. Both congregations welcomed the Jewish soldiers at Fort Bliss. Mt. Sinai, who did not have a permanent building at the time since their new temple was not yet completed, opened a downtown clubroom for Jewish soldiers. 1916, the height of the troop deployment, was a record year for El Paso merchants, even though their trade with Mexico was largely cut off. Haymon Krupp had a close relationship with one of the leaders of the revolution, Pancho Villa. According to family lore, Pancho Villa lived above Krupp’s wholesale dry goods business for eight months in 1910, becoming friendly with the Jewish businessman. Later, Villa bought uniforms for his soldiers from Krupp.

Jewish merchants thrived in El Paso, which became a center for international trade between Mexico and the U.S. Many Jews owned large department stores and wholesale houses. Aaron Goodman owned a retail and wholesale grocery business. Adolph Schwartz, a Hungarian immigrant, opened the Popular Dry Goods Company in 1902. In 1917, it moved into a large six-story building, where Pancho Villa reportedly shopped to outfit his men. Adolph Schwartz’s nephew, Maurice Schwartz, joined him in running the large department store, and through the years several descendants of both Adolph Schwartz and Maurice Schwartz served as presidents of the company. In the 1960s, the business expanded to local malls. After almost a century in business, the Popular Department Store, known to its Spanish-speaking customers as “La Popular,” closed in 1995. Most all of these merchants were bilingual, as Rabbi Zielonka noted in a 1912 letter to the Industrial Removal Office in New York, “in order to earn a living as a merchant it is essential that one speak Spanish as 50% of the population are Mexicans.”

Jewish merchants thrived in El Paso, which became a center for international trade between Mexico and the U.S. Many Jews owned large department stores and wholesale houses. Aaron Goodman owned a retail and wholesale grocery business. Adolph Schwartz, a Hungarian immigrant, opened the Popular Dry Goods Company in 1902. In 1917, it moved into a large six-story building, where Pancho Villa reportedly shopped to outfit his men. Adolph Schwartz’s nephew, Maurice Schwartz, joined him in running the large department store, and through the years several descendants of both Adolph Schwartz and Maurice Schwartz served as presidents of the company. In the 1960s, the business expanded to local malls. After almost a century in business, the Popular Department Store, known to its Spanish-speaking customers as “La Popular,” closed in 1995. Most all of these merchants were bilingual, as Rabbi Zielonka noted in a 1912 letter to the Industrial Removal Office in New York, “in order to earn a living as a merchant it is essential that one speak Spanish as 50% of the population are Mexicans.”

Dora & Rabbi Martin Zielonka.

Dora & Rabbi Martin Zielonka. Photo courtesy of Hollace Weiner

El Paso’s proximity to the border also led an immigration crisis in the 1920s. After the U.S. restricted immigration from Eastern Europe in 1921, a number of Jewish immigrants came into Mexico, with many crossing the border into El Paso illegally. Rabbi Zielonka of Temple Mt. Sinai was concerned about the situation, and worked to convince these immigrants to remain in Mexico. Mt. Sinai created a special committee to help the poor Jewish immigrants living just across the border in Juarez. Zielonka described the situation in a letter to the Industrial Removal Office in 1921, “conditions along the border …seem to be going from bad to worse. The day after I arrived home there were more than thirty men and one man with wife and child on the other side. Our community has raised some funds and we are paying for the rooms and lodging of those without funds, though we cannot carry this on indefinitely.” When dozens of Jewish immigrants were arrested by the border patrol, Rabbi Zielonka intervened to get them deported to Mexico rather than Russia, where Jews faced legal repercussions.

Rabbi Zielonka tried to organize the Jewish community in Mexico so they could care for these immigrants themselves. He had long worked with the Mexican Jewish community, helping to found the Jewish Relief Society in Mexico City in 1908, the first Jewish organization in the country. Zielonka hoped that Mexico City’s growing Jewish community could take in these immigrants. He had Jews meet the boats at the dock in Veracruz and help the newly arrived immigrants get started peddling. Zielonka also convinced the B’nai B’rith to open a settlement house in Mexico City to help these immigrants. He thought that by removing them from the border area, these immigrants would no longer be tempted to cross into America illegally. The rabbi worried that such illegal immigrants “are jeopardizing the good standing of the Jews now in America.” He was also concerned that such actions would embolden nativists who were seeking to restrict immigration even further. According to historian Hollace Weiner, Rabbi Zielonka became “a one-man immigration bureau” whose efforts helped to develop the Jewish community in Mexico City.

Despite Rabbi Zielonka’s effort to funnel these immigrants to Mexico City, a number did cross over into El Paso. By 1927, about 2400 Jews lived in El Paso. The Jewish community shrank to 2250 people during the next decade as the Great Depression took its toll on the city, which saw it overall population decline by 5% during the 1930s. The Depression affected both of El Paso’s congregations as well. Mt. Sinai’s membership dropped from 216 families in 1930 to 180 in 1940. B’nai Zion struggled to pay its rabbi, Joseph Roth, who started teaching at the Texas School of Mines (now the University of Texas at El Paso) to supplement his salary. Rabbi Roth had a Ph.D., and eventually became the chairman of the college’s Philosophy Department, in addition to his duties at B’nai Zion.

Rabbi Zielonka tried to organize the Jewish community in Mexico so they could care for these immigrants themselves. He had long worked with the Mexican Jewish community, helping to found the Jewish Relief Society in Mexico City in 1908, the first Jewish organization in the country. Zielonka hoped that Mexico City’s growing Jewish community could take in these immigrants. He had Jews meet the boats at the dock in Veracruz and help the newly arrived immigrants get started peddling. Zielonka also convinced the B’nai B’rith to open a settlement house in Mexico City to help these immigrants. He thought that by removing them from the border area, these immigrants would no longer be tempted to cross into America illegally. The rabbi worried that such illegal immigrants “are jeopardizing the good standing of the Jews now in America.” He was also concerned that such actions would embolden nativists who were seeking to restrict immigration even further. According to historian Hollace Weiner, Rabbi Zielonka became “a one-man immigration bureau” whose efforts helped to develop the Jewish community in Mexico City.

Despite Rabbi Zielonka’s effort to funnel these immigrants to Mexico City, a number did cross over into El Paso. By 1927, about 2400 Jews lived in El Paso. The Jewish community shrank to 2250 people during the next decade as the Great Depression took its toll on the city, which saw it overall population decline by 5% during the 1930s. The Depression affected both of El Paso’s congregations as well. Mt. Sinai’s membership dropped from 216 families in 1930 to 180 in 1940. B’nai Zion struggled to pay its rabbi, Joseph Roth, who started teaching at the Texas School of Mines (now the University of Texas at El Paso) to supplement his salary. Rabbi Roth had a Ph.D., and eventually became the chairman of the college’s Philosophy Department, in addition to his duties at B’nai Zion.

The original El Paso Holocaust Museum.

The original El Paso Holocaust Museum. Photo courtesy of the El Paso Holocaust Musuem.

World War II and the Post-War Era

World War II was a turning point for El Paso, as Fort Bliss bulged at its seams. The expansion of the military’s presence along with booming oil and copper industries made El Paso into a major city. The city’s population grew from 97,000 people in 1940 to 277,000 in 1960. The Jewish population almost doubled between 1948 and 1960, increasing from 2,000 people to 3,900.

The post-war era was a period of transition for the city’s Jewish congregations as well. After Martin Zielonka died in 1938, Mt. Sinai hired Rabbi Wendell Phillips. A graduate of Stephen Wise’s Jewish Institute of Religion, Rabbi Phillips moved away from the classical Reform practice of Zielonka, even wearing a tallit and robes during services. Whereas Zielonka was adamantly opposed to Zionism, and even blocked the creation of a Hadassah chapter in El Paso, Rabbi Phillips strongly supported the creation of a Jewish state. Like Zielonka, Phillips was very active in the larger community, helping push for a new modern hospital in El Paso. Phillips also insisted that African Americans be allowed to serve on the USO Board during World War II. After serving as a chaplain during the war, Phillips left for a pulpit in Chicago in 1949. His replacement, Rabbi Floyd Fierman, introduced the bar mitzvah, Hebrew instruction in the religious school, and additional Hebrew prayers to services. Soon after he arrived, Rabbi Fierman pushed for a new synagogue to handle the congregation’s growth. Mt. Sinai’s membership more than doubled between 1940 and 1960. The congregation finally dedicated a new synagogue on North Stanton Street in 1962. With a Ph.D. in philosophy, Rabbi Fierman taught at Texas Western College and later wrote several books and articles about the pioneer Jewish settlers of El Paso and the Southwest.

B’nai Zion also flourished during the post-war era. Rabbi Roth continued to lead the congregation, which finally affiliated with the Conservative movement by the end of the 1940s. After 30 years of serving B’nai Zion, Rabbi Roth died in 1953, and was followed by a series of short-termed rabbis. Rabbi Leo Heim came in 1962 and led B’nai Zion for the next nine years. He was replaced by Rabbi Stanley Herman in 1971. By 1958, the congregation had 325 children in its education program and had to construct a new larger school building in 1960 to accommodate them. Although B’nai Zion was no longer Orthodox, they still held daily minyans for their traditional members. In 1974, the congregation voted to give women aliyahs, but still did not count them toward a minyan. By the end of the 1960s, they had fully outgrown their synagogue. The congregation purchased land for a new synagogue in 1969, though it would take 14 years to raise the money and build it. By 1973, B’nai Zion was meeting in the Civic Center for High Holiday services since they could no longer fit into their sanctuary.

World War II was a turning point for El Paso, as Fort Bliss bulged at its seams. The expansion of the military’s presence along with booming oil and copper industries made El Paso into a major city. The city’s population grew from 97,000 people in 1940 to 277,000 in 1960. The Jewish population almost doubled between 1948 and 1960, increasing from 2,000 people to 3,900.

The post-war era was a period of transition for the city’s Jewish congregations as well. After Martin Zielonka died in 1938, Mt. Sinai hired Rabbi Wendell Phillips. A graduate of Stephen Wise’s Jewish Institute of Religion, Rabbi Phillips moved away from the classical Reform practice of Zielonka, even wearing a tallit and robes during services. Whereas Zielonka was adamantly opposed to Zionism, and even blocked the creation of a Hadassah chapter in El Paso, Rabbi Phillips strongly supported the creation of a Jewish state. Like Zielonka, Phillips was very active in the larger community, helping push for a new modern hospital in El Paso. Phillips also insisted that African Americans be allowed to serve on the USO Board during World War II. After serving as a chaplain during the war, Phillips left for a pulpit in Chicago in 1949. His replacement, Rabbi Floyd Fierman, introduced the bar mitzvah, Hebrew instruction in the religious school, and additional Hebrew prayers to services. Soon after he arrived, Rabbi Fierman pushed for a new synagogue to handle the congregation’s growth. Mt. Sinai’s membership more than doubled between 1940 and 1960. The congregation finally dedicated a new synagogue on North Stanton Street in 1962. With a Ph.D. in philosophy, Rabbi Fierman taught at Texas Western College and later wrote several books and articles about the pioneer Jewish settlers of El Paso and the Southwest.

B’nai Zion also flourished during the post-war era. Rabbi Roth continued to lead the congregation, which finally affiliated with the Conservative movement by the end of the 1940s. After 30 years of serving B’nai Zion, Rabbi Roth died in 1953, and was followed by a series of short-termed rabbis. Rabbi Leo Heim came in 1962 and led B’nai Zion for the next nine years. He was replaced by Rabbi Stanley Herman in 1971. By 1958, the congregation had 325 children in its education program and had to construct a new larger school building in 1960 to accommodate them. Although B’nai Zion was no longer Orthodox, they still held daily minyans for their traditional members. In 1974, the congregation voted to give women aliyahs, but still did not count them toward a minyan. By the end of the 1960s, they had fully outgrown their synagogue. The congregation purchased land for a new synagogue in 1969, though it would take 14 years to raise the money and build it. By 1973, B’nai Zion was meeting in the Civic Center for High Holiday services since they could no longer fit into their sanctuary.

B'nai Zion's synagogue, built in 1983.

B'nai Zion's synagogue, built in 1983.

Jewish Organizations in El Paso

While Mt. Sinai and B’nai Zion have been the focal point of the El Paso Jewish community, there have been many other Jewish organizations in the city. In 1897, local Jews founded the Progress Club. This purely social organization attracted the Reform German Jews of Mt. Sinai. By 1910, the Progress Club, which met in rented rooms in various downtown buildings, had 60 members. A B’nai B’rith lodge was founded sometime before 1907. In 1908, members of both congregations created the El Paso Jewish Relief Society to help Jews in need. Later, the Daughters of B’nai Zion worked with the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society of Mt. Sinai on joint charity projects which evolved into the Jewish Federation of Charities. In 1937, El Paso Jews created the Jewish Community Council to oversee all of the fundraising for local and national Jewish charities. This later became the El Paso Jewish Federation, which still functions today.

After World War II, about 75 Holocaust survivors settled in El Paso. The El Paso Jewish Community Council work to resettle these refugees in the city. Emil and Regina Reisel, who escaped from Poland in 1935, led the effort, helping to find them jobs and places to live. Emil Reisel employed several survivors in his wholesale dry goods business. Emil and Regina’s two daughters helped teach the survivors English, as the Reisels became a one-family immigration bureau. Survivor Henry Kellen, who settled in El Paso in 1946, later became a leader in Holocaust education in the city. In 1984, Kellen created a small display about the Holocaust in a conference room in the Jewish Federation building. From this modest beginning grew the El Paso Holocaust Museum, which opened in 1994. Soon after opening, the museum attracted 25,000 student visitors each year as local public schools incorporated Holocaust education into their curriculum. When the building burned down in 2001, the community raised $2.5 million to rebuild the museum, which was completed in 2008.

While Mt. Sinai and B’nai Zion have been the focal point of the El Paso Jewish community, there have been many other Jewish organizations in the city. In 1897, local Jews founded the Progress Club. This purely social organization attracted the Reform German Jews of Mt. Sinai. By 1910, the Progress Club, which met in rented rooms in various downtown buildings, had 60 members. A B’nai B’rith lodge was founded sometime before 1907. In 1908, members of both congregations created the El Paso Jewish Relief Society to help Jews in need. Later, the Daughters of B’nai Zion worked with the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society of Mt. Sinai on joint charity projects which evolved into the Jewish Federation of Charities. In 1937, El Paso Jews created the Jewish Community Council to oversee all of the fundraising for local and national Jewish charities. This later became the El Paso Jewish Federation, which still functions today.

After World War II, about 75 Holocaust survivors settled in El Paso. The El Paso Jewish Community Council work to resettle these refugees in the city. Emil and Regina Reisel, who escaped from Poland in 1935, led the effort, helping to find them jobs and places to live. Emil Reisel employed several survivors in his wholesale dry goods business. Emil and Regina’s two daughters helped teach the survivors English, as the Reisels became a one-family immigration bureau. Survivor Henry Kellen, who settled in El Paso in 1946, later became a leader in Holocaust education in the city. In 1984, Kellen created a small display about the Holocaust in a conference room in the Jewish Federation building. From this modest beginning grew the El Paso Holocaust Museum, which opened in 1994. Soon after opening, the museum attracted 25,000 student visitors each year as local public schools incorporated Holocaust education into their curriculum. When the building burned down in 2001, the community raised $2.5 million to rebuild the museum, which was completed in 2008.

The Jewish Community in El Paso Today

Since 1970, the El Paso Jewish community has remained at a plateau of around 5,000 people. In 1970, Mt. Sinai had 450 families and 200 children in its religious school. B’nai Zion had 420 families at the time. About 30 families belonged to both congregations. Mt. Sinai grew in the 1980s, reaching 524 families by 1990. Rabbi Kenneth Weiss replaced Floyd Fierman who retired in 1979. In 1991, the Reform congregation hired an assistant rabbi to help Rabbi Weiss. After Rabbi Weiss retired in 2002, Assistant Rabbi Larry Bach became the senior spiritual leader at Mt. Sinai. B’nai Zion finally moved into its beautiful new building in 1983. Since 1986, Rabbi Stephen Leon has led the Conservative congregation.

Although the most recent Jewish population estimate for El Paso remains at 5,000 people, there is some evidence of decline. Mt. Sinai’s membership has dropped from 518 families in 1995 to only 344 today. Nevertheless, the El Paso Jewish community remains strong and vibrant. Today, El Paso has a Jewish Community Center, a Jewish Family and Children’s Service, and a Jewish day school. A Chabad House opened in 1986 to offer Orthodox services in the community. There is even a kosher food market in El Paso. While the future course of the El Paso Jewish community may be unclear, it will undoubtedly remain an active center of Jewish life along the Texas-Mexico border.

Although the most recent Jewish population estimate for El Paso remains at 5,000 people, there is some evidence of decline. Mt. Sinai’s membership has dropped from 518 families in 1995 to only 344 today. Nevertheless, the El Paso Jewish community remains strong and vibrant. Today, El Paso has a Jewish Community Center, a Jewish Family and Children’s Service, and a Jewish day school. A Chabad House opened in 1986 to offer Orthodox services in the community. There is even a kosher food market in El Paso. While the future course of the El Paso Jewish community may be unclear, it will undoubtedly remain an active center of Jewish life along the Texas-Mexico border.