Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Fort Worth, Texas

Fort Worth: Historical Overview

|

Fort Worth’s name reflects the city’s origins as a frontier outpost for the U.S. Army. Established on the banks of the Trinity River in 1849, the fort was named for William Jennings Worth, a hero of the Mexican-American War. When the army left the area in 1853, the handful of merchants who had set up shop there remained and were soon joined by a trickle of new settlers, buoyed by Fort Worth’s being named the seat of Tarrant County in 1860. While the turmoil of the Civil War and its aftermath took its toll on the fledgling town, which saw its population dip to only 175 people, Fort Worth soon rebounded thanks to the arrival of thousands of cattle and the cowboys herding them. By the 1870s, Fort Worth had become a major stop for north-bound cattle drives. Cattle buyers, hotels, saloons, and various other businesses set up shop in Fort Worth. In 1876, the Texas and Pacific Railroad made the town its western terminus; soon after, several other railroads laid track into the city, linking this once remote fort to the entire country.

Jews have lived in Fort Worth since the mid-19th century. Today, Fort Worth is home to a growing and vibrant Jewish community. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Fort Worth

Simon Gabert.

Simon Gabert. Photo courtesy of Beth-El Archives

Early Settlers

A small number of Jews were drawn to Fort Worth during its early years. Among the first were Simon Gabert, who came in 1856, and Jacob Samuels, who opened a dry goods store in the town the following year. An immigrant from Poland, Samuels quickly embraced his adopted homeland of the South, signing up to fight for the Confederacy. When he died many years later in 1906, Samuels had the Confederate battle flag carved into his tombstone.

In 1874, Fort Worth Jews established a B’nai B’rith Lodge, the first Jewish organization to be founded in the city; Jacob Samuels was among its 23 founding members. Five years later, John Peter Smith, a prominent local Gentile, donated land to the Jewish community for a cemetery, as Jews founded the Emanuel Hebrew Association to oversee and maintain the burial ground.

When newspaper editor Charles Wessolowsky visited Fort Worth in 1879, he found about 100 Jews, all of whom he claimed “are industrious, hardworking and energetic people.” They were thriving in business, but indifferent to organized religious life. Rabbi Abraham Blum of Galveston's B'nai Israel Congregation had visited the city earlier in 1879 and helped create a religious school. Wessolowsky reported that while the three teachers were doing a good job, “there seems to be a lack of zeal among parents” for educating their children about Judaism. Indeed, the school soon disbanded, as did Fort Worth’s B’nai B’rith lodge. Even the Emanuel Hebrew Association became inactive. In 1888, one local Jew reported to the American Israelite newspaper that “we have no congregation, no B’nai B’rith, and the only society we have is the cemetery association…and now interest in that most laudable enterprise is flagging.” This early Jewish community, which was large enough to support such organizations, was not very interested in building religious institutions. Fort Worth Jews would not establish a congregation until 1892. In this regard, the Jewish community was not that different than the rest of Fort Worth's population; by 1900, Fort Worth had 26,000 residents, but only 15 churches. Saloons, brothels, and gambling dens were far more common than houses of worship in this frontier town’s early years.

A small number of Jews were drawn to Fort Worth during its early years. Among the first were Simon Gabert, who came in 1856, and Jacob Samuels, who opened a dry goods store in the town the following year. An immigrant from Poland, Samuels quickly embraced his adopted homeland of the South, signing up to fight for the Confederacy. When he died many years later in 1906, Samuels had the Confederate battle flag carved into his tombstone.

In 1874, Fort Worth Jews established a B’nai B’rith Lodge, the first Jewish organization to be founded in the city; Jacob Samuels was among its 23 founding members. Five years later, John Peter Smith, a prominent local Gentile, donated land to the Jewish community for a cemetery, as Jews founded the Emanuel Hebrew Association to oversee and maintain the burial ground.

When newspaper editor Charles Wessolowsky visited Fort Worth in 1879, he found about 100 Jews, all of whom he claimed “are industrious, hardworking and energetic people.” They were thriving in business, but indifferent to organized religious life. Rabbi Abraham Blum of Galveston's B'nai Israel Congregation had visited the city earlier in 1879 and helped create a religious school. Wessolowsky reported that while the three teachers were doing a good job, “there seems to be a lack of zeal among parents” for educating their children about Judaism. Indeed, the school soon disbanded, as did Fort Worth’s B’nai B’rith lodge. Even the Emanuel Hebrew Association became inactive. In 1888, one local Jew reported to the American Israelite newspaper that “we have no congregation, no B’nai B’rith, and the only society we have is the cemetery association…and now interest in that most laudable enterprise is flagging.” This early Jewish community, which was large enough to support such organizations, was not very interested in building religious institutions. Fort Worth Jews would not establish a congregation until 1892. In this regard, the Jewish community was not that different than the rest of Fort Worth's population; by 1900, Fort Worth had 26,000 residents, but only 15 churches. Saloons, brothels, and gambling dens were far more common than houses of worship in this frontier town’s early years.

Wedding portrait of Sam & Betty

Wedding portrait of Sam & Betty

Rosen. Photo courtesy of Beth-El

Congregation Archives.

Early Jewish Businesses in Fort Worth

As a booming town, Fort Worth offered significant economic opportunity and Jews quickly flourished there. Nathaniel and Jacob Washer came to Fort Worth in 1882 and opened Washer Brother Clothiers, which specialized in selling fine men's clothing and hats. While Nathaniel later left to open a store in San Antonio, Jacob remained to become a leader of the local business community, serving as president of the Fort Worth Board of Trade before his death in 1906. The Washer Brothers store remained in business through the 1960s. Sam Rosen started out as a peddler before opening a clothing store, though he made his name in real estate. When the Armour and Swift meat packing companies opened operations in the city in 1902, Rosen bought land just west of the new plants. Rosen built houses in this new subdivision to appeal to the meat packers and even built a streetcar line from downtown to the new area, which became known as Rosen Heights. Henry Greenwall, a regional theater impresario, bought the Fort Worth Opera House in 1890 and hired his brother Philip to manage it. Philip changed its name to Greenwall’s Opera House and booked national performers like Sarah Bernhardt and John Philip Sousa.

Early Fort Worth Jews were not just involved in business. A handful were professionals, including several prominent lawyers. Sidney Samuels, the son of Jacob Samuels, was elected city attorney in 1908, while U.M. Simon and Max Mayer spent several years as assistant county attorneys in the first decade of the 20th century. Theodore Mack was another leading Fort Worth attorney during this period.

As a booming town, Fort Worth offered significant economic opportunity and Jews quickly flourished there. Nathaniel and Jacob Washer came to Fort Worth in 1882 and opened Washer Brother Clothiers, which specialized in selling fine men's clothing and hats. While Nathaniel later left to open a store in San Antonio, Jacob remained to become a leader of the local business community, serving as president of the Fort Worth Board of Trade before his death in 1906. The Washer Brothers store remained in business through the 1960s. Sam Rosen started out as a peddler before opening a clothing store, though he made his name in real estate. When the Armour and Swift meat packing companies opened operations in the city in 1902, Rosen bought land just west of the new plants. Rosen built houses in this new subdivision to appeal to the meat packers and even built a streetcar line from downtown to the new area, which became known as Rosen Heights. Henry Greenwall, a regional theater impresario, bought the Fort Worth Opera House in 1890 and hired his brother Philip to manage it. Philip changed its name to Greenwall’s Opera House and booked national performers like Sarah Bernhardt and John Philip Sousa.

Early Fort Worth Jews were not just involved in business. A handful were professionals, including several prominent lawyers. Sidney Samuels, the son of Jacob Samuels, was elected city attorney in 1908, while U.M. Simon and Max Mayer spent several years as assistant county attorneys in the first decade of the 20th century. Theodore Mack was another leading Fort Worth attorney during this period.

Moses Shamblum

Moses Shamblum

Organized Jewish Life in Fort Worth

When Russian immigrant Moses Shanblum arrived in Fort Worth in 1887, he was appalled to find no Jewish congregations in the growing city. All he found in the way of organized religious life was one small group of six families who would meet together in their homes for the High Holidays. In response, Shanblum started a daily minyan that met in houses and stores. A few years later, Shanblum helped lead the way in founding the city’s first congregation, Ahavath Sholom, established in 1892 with 31 founding members, most of whom were immigrants from Russia and Poland. The fledgling congregation was Orthodox, with its minutes kept in Yiddish. Even though most members were newcomers to the United States, they moved quickly to build a synagogue. Shanblum led this effort, going door to door and store to store in the Jewish community soliciting donations for the building fund. In 1893 Ahavath Sholom bought land. Even though the congregation only had $14 left in its bank account after the purchase, they began to plan building a synagogue. By 1895, the congregation had constructed a modest, one-story wood-frame synagogue for $600. That same year, the congregation hired a shochet (kosher butcher) to help members maintain the Orthodox dietary laws.

Despite this progress, Ahavath Sholom struggled financially in its early years. At one point, half of its members were suspended for being in arrears on their dues and the congregation had to appeal to Jews in Dallas and Waco for financial assistance. By 1900, Ahavath Sholom had 30 members and an annual dues income of $350. Although Ahavath Sholom was the only Jewish congregation in the city at the time, many Fort Jews did not belong to it. The more assimilated Reform Jews of the city refused to join the Orthodox shul even though they did not yet have a congregation of their own.

When Russian immigrant Moses Shanblum arrived in Fort Worth in 1887, he was appalled to find no Jewish congregations in the growing city. All he found in the way of organized religious life was one small group of six families who would meet together in their homes for the High Holidays. In response, Shanblum started a daily minyan that met in houses and stores. A few years later, Shanblum helped lead the way in founding the city’s first congregation, Ahavath Sholom, established in 1892 with 31 founding members, most of whom were immigrants from Russia and Poland. The fledgling congregation was Orthodox, with its minutes kept in Yiddish. Even though most members were newcomers to the United States, they moved quickly to build a synagogue. Shanblum led this effort, going door to door and store to store in the Jewish community soliciting donations for the building fund. In 1893 Ahavath Sholom bought land. Even though the congregation only had $14 left in its bank account after the purchase, they began to plan building a synagogue. By 1895, the congregation had constructed a modest, one-story wood-frame synagogue for $600. That same year, the congregation hired a shochet (kosher butcher) to help members maintain the Orthodox dietary laws.

Despite this progress, Ahavath Sholom struggled financially in its early years. At one point, half of its members were suspended for being in arrears on their dues and the congregation had to appeal to Jews in Dallas and Waco for financial assistance. By 1900, Ahavath Sholom had 30 members and an annual dues income of $350. Although Ahavath Sholom was the only Jewish congregation in the city at the time, many Fort Jews did not belong to it. The more assimilated Reform Jews of the city refused to join the Orthodox shul even though they did not yet have a congregation of their own.

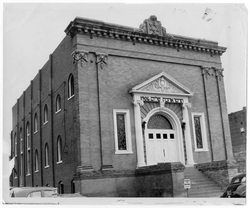

Ahavath Sholom's synagogue,

Ahavath Sholom's synagogue,

dedicated in 1906. Photo courtesy

of Fort Worth Jewish Archives.

Regardless of these challenges, the Orthodox members of the congregation pressed ahead. Increased immigration led to a boom in Ahavath Sholom’s membership, which grew to 75 members by 1907. When they wanted a synagogue location closer to downtown, they bought land in 1899 and two years later moved their small building to the new site. In 1903, they started a religious school which soon grew into a six-day-a-week Talmud Torah, and hired Rabbi G. Halpern to run it. The women of the congregation, led by Sarah Shanblum, started the Ladies Hebrew Relief Society in 1903 to help newly arriving Jewish immigrants, especially those sent by the New York-based Industrial Removal Office. Ahavath Sholom added a mikvah (ritual bath) to its facility in 1904. Two years later, the congregation dedicated a new brick synagogue on the same site. In 1908, they hired Rabbi Charles Blumenthal, who led the congregation for the next four years before leaving. Blumenthal returned to lead the congregation for a brief time a few years later, and even came back for a year in 1945.

Even though most of its members were recent immigrants, the Jews of Ahavath Sholom did not shy away from speaking out on world issues. After the brutal Kishnieff pogrom in Russia in 1903, the congregation organized a mass protest meeting at the City Hall Auditorium which drew 325 people. Mayor Thomas J. Powell, U.S. Congressman O.W. Gillespie, and leading local ministers spoke during the event, which also featured the singing of “Dixie.” Leaders of Ahavath Sholom issued a proclamation, signed by several local elected officials, denouncing the Russian czar for allowing such anti-Semitic violence to occur.

The Orthodox congregation continued to grow in the 1910s. In 1914, Ahavath Sholom built a Hebrew Institute, which had new classrooms, a library, auditorium, and a rabbi’s office. Later, a third story with a gym and locker room was added to the building. By 1919, Ahavath Sholom had 125 members, $3000 in annual dues income, and 130 students in its daily religious school. A Ladies Auxiliary was founded in 1915 which oversaw the Sunday school and kosher kitchen. Ahavath Sholom continued to employ full-time rabbis through the 1910s and 1920s. In 1929, the congregation hired Rabbi Philip Graubert, who led Ahavath Sholom for the next 15 years.

Even though most of its members were recent immigrants, the Jews of Ahavath Sholom did not shy away from speaking out on world issues. After the brutal Kishnieff pogrom in Russia in 1903, the congregation organized a mass protest meeting at the City Hall Auditorium which drew 325 people. Mayor Thomas J. Powell, U.S. Congressman O.W. Gillespie, and leading local ministers spoke during the event, which also featured the singing of “Dixie.” Leaders of Ahavath Sholom issued a proclamation, signed by several local elected officials, denouncing the Russian czar for allowing such anti-Semitic violence to occur.

The Orthodox congregation continued to grow in the 1910s. In 1914, Ahavath Sholom built a Hebrew Institute, which had new classrooms, a library, auditorium, and a rabbi’s office. Later, a third story with a gym and locker room was added to the building. By 1919, Ahavath Sholom had 125 members, $3000 in annual dues income, and 130 students in its daily religious school. A Ladies Auxiliary was founded in 1915 which oversaw the Sunday school and kosher kitchen. Ahavath Sholom continued to employ full-time rabbis through the 1910s and 1920s. In 1929, the congregation hired Rabbi Philip Graubert, who led Ahavath Sholom for the next 15 years.

Ahavath Sholom Sunday School,

Ahavath Sholom Sunday School,

1925. Photo coutesy of Fort Worth

Jewish Archives.

In most Southern cities with two Jewish congregations, the Reform came first with the Orthodox following. In Fort Worth, this order was reversed. Although the presence of Reform Jews preceded the establishment of Ahavath Sholom, they did not organize their own congregation until a full decade after newly arrived Orthodox Jews started theirs. Leading Jewish citizens like Jacob Washer and Theodore Mack did not belong to Ahavath Sholom and evinced little interest in religious life. By the 1890s, Reform Jews were meeting together for lay led services on the High Holidays only. Finally, in 1900 Henry Gernsbacher moved to town from nearby Weatherford and began to push the city’s assimilated Reform Jews to organize. In 1901 Gernsbacher reestablished the city’s defunct B’nai B’rith chapter and pushed for the creation of a Sunday school. Finally, in 1902, 43 of the city’s Reform Jews founded Congregation Beth-El. Sam Levy, a prominent wholesale liquor dealer, was elected its first president. A few members of Ahavath Sholom left to join Beth-El, including David Brown, who had recently served as president of the Orthodox congregation from 1899 to 1901.

Of these 43 charter members, 30 could be found in the U.S. Census. Of these 30, 17 were immigrants, primarily from Germany, though most had been in the United States for several decades. At the time of Beth-El’s founding in 1902, their average age was 40. Two-thirds owned a business, but only 40% owned their own home. They ran a wide array of businesses, including a theater, ice manufacturing company, two saloons, and a jewelry store, though 30% owned a clothing or dry goods store. According to historian Hollace Weiner, the founding members of Beth-El were closely tied together by marriage and business partnerships. Most of the 43 founding members were part of just a handful of extended families.

Soon after organizing, the members of Beth-El rented a building and started holding services on Friday nights. They hired Rabbi Solomon Philo and borrowed a Torah from Temple Emanu-El in Dallas for their first High Holiday services. Rabbi Philo proved to be unpopular and interest waned among Beth-El’s members. The congregation soon became inactive and did not even hold High Holiday services in 1903. The local Council of Jewish Women chapter, which had been founded in 1901, stepped into the breach and brought in Rabbi George Zepin from the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1904 to help revive Beth-El.

Of these 43 charter members, 30 could be found in the U.S. Census. Of these 30, 17 were immigrants, primarily from Germany, though most had been in the United States for several decades. At the time of Beth-El’s founding in 1902, their average age was 40. Two-thirds owned a business, but only 40% owned their own home. They ran a wide array of businesses, including a theater, ice manufacturing company, two saloons, and a jewelry store, though 30% owned a clothing or dry goods store. According to historian Hollace Weiner, the founding members of Beth-El were closely tied together by marriage and business partnerships. Most of the 43 founding members were part of just a handful of extended families.

Soon after organizing, the members of Beth-El rented a building and started holding services on Friday nights. They hired Rabbi Solomon Philo and borrowed a Torah from Temple Emanu-El in Dallas for their first High Holiday services. Rabbi Philo proved to be unpopular and interest waned among Beth-El’s members. The congregation soon became inactive and did not even hold High Holiday services in 1903. The local Council of Jewish Women chapter, which had been founded in 1901, stepped into the breach and brought in Rabbi George Zepin from the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1904 to help revive Beth-El.

Beth-El's synagogue in 1948.

Beth-El's synagogue in 1948. Photo courtesy of Beth-El archives.

Zepin was successful and got Beth-El to hire the young and energetic Joseph Jasin as their rabbi. Membership soon grew to 60 households as Jasin organized a religious school and led weekly Shabbat services; Beth-El had formally affiliated with the UAHC by 1907. The group met at a spiritualist temple, a fact which upset many of the members of the Council of Jewish Women, who pushed the revitalized congregation to build a synagogue. They council led the way by selling home-cooked dinners during the annual Fort Worth Fat Stock Show to raise money for the building fund. Finally, in 1908, with 80 members, Beth-El dedicated its first temple at 5th and Taylor Streets. Beth-El grew steadily, and by 1920, built a new larger synagogue to accommodate its 120 members. A Sisterhood was established in 1913, which worked to support both the congregation and those in need. During World War I, the Sisterhood made bandages and sewed hospital gowns. After the war, the Sisterhood used a dedicated sewing room to make baby clothes for the local children’s hospital.

When Rabbi Jasin left in 1908 to become an official with the Federation of American Zionists, Beth-El hired George Zepin to replace him, though he stayed for only two years. In 1910, Beth El hired Rabbi George Fox, who spent a dozen years in Fort Worth. Rabbi Fox was very active in civic work and social causes, serving as head of the city charity commission. When a group of 20 Jewish prostitutes started plying their trade in the city’s “Hell’s Half Acre” section, Fox used his influence to have them arrested and deported fearing that they would make the local Jewish community look bad. Fox also challenged the racial segregation of the city, refusing to speak at a Liberty Bond luncheon until black volunteers were allowed to take part in the meal. Rabbi Fox left in 1922 and was replaced by Harry Merfeld. Beth-El suffered during the Great Depression as congregation leaders were forced to go door-to-door to raise money to pay Rabbi Merfeld’s salary. World War II brought new prosperity to both Fort Worth and Beth El.

When Rabbi Jasin left in 1908 to become an official with the Federation of American Zionists, Beth-El hired George Zepin to replace him, though he stayed for only two years. In 1910, Beth El hired Rabbi George Fox, who spent a dozen years in Fort Worth. Rabbi Fox was very active in civic work and social causes, serving as head of the city charity commission. When a group of 20 Jewish prostitutes started plying their trade in the city’s “Hell’s Half Acre” section, Fox used his influence to have them arrested and deported fearing that they would make the local Jewish community look bad. Fox also challenged the racial segregation of the city, refusing to speak at a Liberty Bond luncheon until black volunteers were allowed to take part in the meal. Rabbi Fox left in 1922 and was replaced by Harry Merfeld. Beth-El suffered during the Great Depression as congregation leaders were forced to go door-to-door to raise money to pay Rabbi Merfeld’s salary. World War II brought new prosperity to both Fort Worth and Beth El.

Polly Mack, longtime president of

Polly Mack, longtime president of

the Fort Worth Council of Jewish

Women. Photo courtesy of Beth-El

Congregation Archives.

Jewish Organizations in Fort Worth

In addition to the two congregations, Fort Worth Jews established various other Jewish organizations. They founded a Young Men’s Hebrew Association in 1895, though it became inactive during the following decade. It was reorganized in 1912, under the leadership of Rabbi Charles Blumenthal of Ahavath Sholom, meeting at the Orthodox congregation’s Hebrew Institute. B’nai B’rith was reorganized in 1902, and quickly became active. In 1905, the lodge defended Jewish peddlers in Fort Worth, successfully fighting off an effort to restrict street vending in the city. They also created a fund to help the poor who needed medical treatment at the county hospital.

In addition to supporting Beth-El Congregation in its early years, the Council of Jewish Women started an Americanization school in 1907 to help newly arrived immigrants of all ethnic and religious backgrounds. The school taught its students English as well as American politics and culture. Though the school was discontinued after immigration declined in the 1920s, it was restarted after World War II and remained active until 1973, helping new generations of Fort Worth immigrants adjust to life in the United States. Also, in 1918, the CJW, led by its president Polly Mack, helped to create the Fort Worth Free Baby Hospital.

Fort Worth was a stronghold of Zionism in Texas. Ahavath Zion, the city’s first Zionist organization, was founded in 1900 with 22 members. Joseph Jacobs was its first president, while Israel Mehl served as vice-president. Mehl emerged as an important leader of Zionism in the state, helping to organize the Texas Zionist Association, of which he served as president. Mehl was extremely active in the Fort Worth Jewish community, serving as president of the Hebrew Relief Society, the Hebrew Free Loan Association, B’nai B’rith, Ahavath Sholom, and the Hebrew Institute at various times. In 1907, the Young Men and Daughters of Zion, which catered to teenagers, was founded. The group, which had 75 members in 1907, held parties, picnics, and educational programs. While most Fort Worth Zionists were affiliated with the Orthodox Ahavath Sholom, a number of Beth-El members, including its first rabbi Joseph Jasin, also supported the goal of a Jewish homeland. Thus, Zionism was not as divisive in Fort Worth as it was in other Texas cities.

In addition to the two congregations, Fort Worth Jews established various other Jewish organizations. They founded a Young Men’s Hebrew Association in 1895, though it became inactive during the following decade. It was reorganized in 1912, under the leadership of Rabbi Charles Blumenthal of Ahavath Sholom, meeting at the Orthodox congregation’s Hebrew Institute. B’nai B’rith was reorganized in 1902, and quickly became active. In 1905, the lodge defended Jewish peddlers in Fort Worth, successfully fighting off an effort to restrict street vending in the city. They also created a fund to help the poor who needed medical treatment at the county hospital.

In addition to supporting Beth-El Congregation in its early years, the Council of Jewish Women started an Americanization school in 1907 to help newly arrived immigrants of all ethnic and religious backgrounds. The school taught its students English as well as American politics and culture. Though the school was discontinued after immigration declined in the 1920s, it was restarted after World War II and remained active until 1973, helping new generations of Fort Worth immigrants adjust to life in the United States. Also, in 1918, the CJW, led by its president Polly Mack, helped to create the Fort Worth Free Baby Hospital.

Fort Worth was a stronghold of Zionism in Texas. Ahavath Zion, the city’s first Zionist organization, was founded in 1900 with 22 members. Joseph Jacobs was its first president, while Israel Mehl served as vice-president. Mehl emerged as an important leader of Zionism in the state, helping to organize the Texas Zionist Association, of which he served as president. Mehl was extremely active in the Fort Worth Jewish community, serving as president of the Hebrew Relief Society, the Hebrew Free Loan Association, B’nai B’rith, Ahavath Sholom, and the Hebrew Institute at various times. In 1907, the Young Men and Daughters of Zion, which catered to teenagers, was founded. The group, which had 75 members in 1907, held parties, picnics, and educational programs. While most Fort Worth Zionists were affiliated with the Orthodox Ahavath Sholom, a number of Beth-El members, including its first rabbi Joseph Jasin, also supported the goal of a Jewish homeland. Thus, Zionism was not as divisive in Fort Worth as it was in other Texas cities.

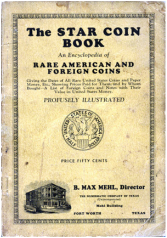

Max Mehl's "profusely illustrated" coin guidebook

Max Mehl's "profusely illustrated" coin guidebook

Early 20th Century Businesses

In the first half of the 20th century, Fort Worth Jews remained concentrated in business. Several Jews owned retail stores downtown on Exchange Street, including Seymour Drescher, who owned the White Front Store, and Samuel Sheinberg, who had the Western Store. Will and Henry Nurenberg came to Fort Worth in 1903 and built a flourishing lumber business. Abraham Luskey learned boot making in the Russian army, later using this skill to open a western wear store after he immigrated to Fort Worth. Luskey’s store eventually grew into a regional chain. Perhaps the most unique and well known business was started by B. Max Mehl, whose father had brought the young boy to Fort Worth from Lithuania in 1892. An interest in coins led Max Mehl to start a numismatic business. Mehl became a pioneer in the coin collecting field, publishing a widely distributed price booklet and advertising in national magazines. By 1924, he was spending $50,000 a year on advertising alone and sold his coin pricing guides around the country via mail order. Indeed, a significant amount of the mail coming to Fort Worth went to the Mehl Numismatic Building, which he opened in 1915.

Presentation

Despite their business success, Fort Worth Jews were excluded from many of the elite social organizations in the city. The city’s elite debutante scene was closed to Jews in the mid-20th century. In response, the Jewish community, led by the Beth-El Sisterhood, created its own version, called “Presentation,” in 1936. For the next 17 years, each of the city’s 13 Jewish organizations would nominate a young woman to “debut” in a large ball held annually at the Blackstone Hotel. This system ensured that all segments of the Fort Worth Jewish community would be included, and indeed Presentation was an event that brought together both the Reform and Orthodox congregations. The young ladies presented were featured in the local newspaper. While Presentation was a response to the social exclusion Fort Worth Jews faced, it also reflected a desire on the part of Jewish parents to have their children socialize with and ultimately marry other Jews.

In the first half of the 20th century, Fort Worth Jews remained concentrated in business. Several Jews owned retail stores downtown on Exchange Street, including Seymour Drescher, who owned the White Front Store, and Samuel Sheinberg, who had the Western Store. Will and Henry Nurenberg came to Fort Worth in 1903 and built a flourishing lumber business. Abraham Luskey learned boot making in the Russian army, later using this skill to open a western wear store after he immigrated to Fort Worth. Luskey’s store eventually grew into a regional chain. Perhaps the most unique and well known business was started by B. Max Mehl, whose father had brought the young boy to Fort Worth from Lithuania in 1892. An interest in coins led Max Mehl to start a numismatic business. Mehl became a pioneer in the coin collecting field, publishing a widely distributed price booklet and advertising in national magazines. By 1924, he was spending $50,000 a year on advertising alone and sold his coin pricing guides around the country via mail order. Indeed, a significant amount of the mail coming to Fort Worth went to the Mehl Numismatic Building, which he opened in 1915.

Presentation

Despite their business success, Fort Worth Jews were excluded from many of the elite social organizations in the city. The city’s elite debutante scene was closed to Jews in the mid-20th century. In response, the Jewish community, led by the Beth-El Sisterhood, created its own version, called “Presentation,” in 1936. For the next 17 years, each of the city’s 13 Jewish organizations would nominate a young woman to “debut” in a large ball held annually at the Blackstone Hotel. This system ensured that all segments of the Fort Worth Jewish community would be included, and indeed Presentation was an event that brought together both the Reform and Orthodox congregations. The young ladies presented were featured in the local newspaper. While Presentation was a response to the social exclusion Fort Worth Jews faced, it also reflected a desire on the part of Jewish parents to have their children socialize with and ultimately marry other Jews.

|

A Growing Community

Oil supplanted cattle as the central engine of Fort Worth’s economy in the 20th century. World War II brought the aviation industry and Carswell Air Force Base, as the city’s population doubled between 1940 and 1960. The Jewish community grew as well, though not as dramatically, increasing from 2,200 people in 1937 to 2,800 in 1960. At the middle of the 20th century, Jewish life in the city revolved around its two congregations to which most all Fort Worth Jews belonged. With 275 families, Ahavath Sholom had outgrown its synagogue by the end of World War II. In 1952, they dedicated a new larger building on 8th and Myrtle streets. The congregation still held daily Orthodox minyans, but had allowed mixed-gender seating during Shabbat services starting in the 1940s. When the only kosher butcher shop in Fort Worth closed in 1959, Ahavath Sholom made arrangements with a local poultry company to slaughter chickens for members of the congregation. Still nominally Orthodox, Ahavath Sholom was not affiliated with any national movement. |

|

Rabbi Isadore Garsek led the congregation from 1946 to 1979, a time of growth and transition for Ahavath Sholom. By 1973, the congregation had 460 families, though many of them had moved to the southwest part of the city. Ahavath Sholom followed suit, buying land on Hulen and Briarhaven streets in 1972. Eight years later, they dedicated a new synagogue on the site. The new chapel had a flashing light on its roof that would signal whether they needed additional worshipers to make the minyan of ten men. The growth in the congregation continued, reaching 600 families by 1992. In 1991, Ahavath Sholom changed its constitution, declaring itself to be a Conservative congregation. The following year, they affiliated with the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism and gave women full religious rights in the congregation.

Beth-El started the post-war era with a calamity. One night in 1946, the local B’nai B’rith lodge held a poker night in the temple’s social hall. A smoldering cigar butt later started a fire that consumed the entire building. All that was saved were the two Torahs, a piano, and a yahrzeit memorial board. A local Baptist congregation invited Beth-El to meet in their church until the temple was rebuilt. When it was completed in 1948, the Beth-El board passed a rule banning gambling and card playing from the new temple. Despite the fire, Beth-El flourished during this era, growing from 120 families in 1940 to 350 by 1962. That same year, Beth-El dedicated a new education wing to handle the growing number of children in its religious school. Rabbi Robert Schur came to Beth-El in 1956, leading the Reform congregation for the next 30 years. Rabbi Schur was very active in the larger community, especially in the area of civil rights, taking part in a bi-racial march to City Hall in 1965 to protest the shooting of Reverend James Reeb in Selma, Alabama.

Beth-El started the post-war era with a calamity. One night in 1946, the local B’nai B’rith lodge held a poker night in the temple’s social hall. A smoldering cigar butt later started a fire that consumed the entire building. All that was saved were the two Torahs, a piano, and a yahrzeit memorial board. A local Baptist congregation invited Beth-El to meet in their church until the temple was rebuilt. When it was completed in 1948, the Beth-El board passed a rule banning gambling and card playing from the new temple. Despite the fire, Beth-El flourished during this era, growing from 120 families in 1940 to 350 by 1962. That same year, Beth-El dedicated a new education wing to handle the growing number of children in its religious school. Rabbi Robert Schur came to Beth-El in 1956, leading the Reform congregation for the next 30 years. Rabbi Schur was very active in the larger community, especially in the area of civil rights, taking part in a bi-racial march to City Hall in 1965 to protest the shooting of Reverend James Reeb in Selma, Alabama.

Ahavath Sholom's current synagogue,

Ahavath Sholom's current synagogue,

completed in 1972.

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler.

Civic and Political Engagement

By the mid-20th century, Fort Worth Jews were actively involved in civic affairs. Dr. Abe Greines,a former football star at Texas Christian University, was a local physician for over 60 years. In 1953 he became the first Jew to serve on the Fort Worth School Board. Edwin Schwarz was a pioneer pediatrician in Fort Worth, opening the city’s first pediatric practice and serving as the first chief of staff at Cook Children’s Hospital. Manny Rosenthal who became president of his family’s Standard Meat Company in 1959, was a leading philanthropist in Fort Worth, endowing professorships at Texas Christian University as well as Texas A&M. He and his wife Rosalyn became big financial supporters of the arts in the city. Marcus Ginsburg became a nationally prominent attorney, serving on the United States Commission for UNESCO from 1959 to 1965. Later, Ginsburg was a national vice president of the American Jewish Committee and head of its commission on international affairs.

By the mid-20th century, Fort Worth Jews were actively involved in civic affairs. Dr. Abe Greines,a former football star at Texas Christian University, was a local physician for over 60 years. In 1953 he became the first Jew to serve on the Fort Worth School Board. Edwin Schwarz was a pioneer pediatrician in Fort Worth, opening the city’s first pediatric practice and serving as the first chief of staff at Cook Children’s Hospital. Manny Rosenthal who became president of his family’s Standard Meat Company in 1959, was a leading philanthropist in Fort Worth, endowing professorships at Texas Christian University as well as Texas A&M. He and his wife Rosalyn became big financial supporters of the arts in the city. Marcus Ginsburg became a nationally prominent attorney, serving on the United States Commission for UNESCO from 1959 to 1965. Later, Ginsburg was a national vice president of the American Jewish Committee and head of its commission on international affairs.

U.S. Representative Martin Frost

U.S. Representative Martin Frost

Fort Worth Jews also became active in politics. Local lawyer Bayard Friedman was elected to the city council in 1963, and became mayor when his fellow council members selected him for the job. During his one term in office, the Republican Friedman helped lead the negotiation with Dallas to build DFW airport between the two cities and helped pass bond issues for a downtown convention center and new public schools. After leaving office, Friedman became president of Fort Worth National Bank. Martin Frost, who grew up at Beth-El, was first elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1978. Over the course of his 13 terms in office, Frost became an influential leader within the House Democratic Party caucus. After a partisan redistricting effort that specifically targeted him, Frost lost his bid for re-election in 2004.

The Jewish Community in Fort Worth Today

Beth-El's new synagogue,

Beth-El's new synagogue,

dedicated in 2000.

Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler.

Over the end of the 20th century, the Fort Worth Jewish community continued to grow, increasing from 3,600 people in 1984 to 5,000 in 2001. The city’s Jewish congregations grew as well. In 2010, Beth-El enjoyed its largest membership ever with 477 families. In 2000, Beth-El built a beautiful new $11 million temple, just down the street from Ahavath Sholom in the southwest part of the city, where many of their members now lived. With the tremendous overall growth in the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex, the Jewish community of Fort Worth seems poised to flourish well into the 21st century.

Sources

This history is deeply indebted to the work of Hollace Ava Weiner, whose well researched and beautifully written accounts of Fort Worth Jewish history are essential reading for those interested in the subject. See, in particular, “Whistling Dixie while Humming Hatikvah: Acculturation and Activism among Orthodox Jews in Fort Worth” American Jewish History, vol. 93, no. 2 (June 2007); “Fort Worth Jewry: A Sesquicentennial Snapshot”; Beth El Congregation Centennial, 1902-2002”; and Jewish “Junior League”: The Rise and Demise of the Fort Worth Council of Jewish Women (College Station: Texas A&M Press, 2008).