Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Gainesville, Texas

Gainesville: Historical Overview

|

Gainesville, Texas, is a city more characteristic of the Great American West than Dixie. Located 67 miles north of Dallas in Cooke County, Gainesville’s history has been shaped by cattle wranglers, gamblers, saloon owners, and other archetypes of the Wild West.

In 1847, intensive settlement began in the Gainesville area with the construction of Fort Fitzhugh. That same year, Cooke County was chartered by the Texas legislature. Gainesville itself was established on a 40-acre tract of land donated to the Republic of Texas by Mary E. Clark. The post-Civil War years brought the cattle industry to Gainesville as the western stem of the Chisholm Trail came into heavy use following changes in Missouri cattle herding laws. |

The majority of the region’s cattle business began to channel through the Red River Valley en route to the railhead of the Kansas Pacific Railway in Abilene. Gainesville’s proximity to the Shawnee cattle trail brought in further herding-related businesses—most notably hotels, saloons, and general stores. In 1879, the Missouri, Kansas and Texas rail system came to Gainesville and, in 1886, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe added the town to its expanding rail line. With the increase in transport opportunities, agriculture began to replace cattle herding as the economy’s main engine.

Gainesville’s rise to economic prominence attracted growing numbers of fortune seekers, including Jews. As the frontier began to close around the turn of the 20th century, the small Jewish community of Gainesville experienced its heyday. United Hebrew Congregation, once located at the southeast corner of Broadway and Red River, had a thriving and active congregation within the confines of a small town whose population did not exceed 10,000 people until the 1950s.

Gainesville’s Jews played a leading role in the local dry goods industry as well as the liquor business and were deeply involved in civic life. However, the story of Jews in Gainesville follows the boomtown trend: while Jewish immigrants and migrants flocked to the area when the cattle industry thrived and business was good, a variety of factors caused business in Gainesville to dwindle. By the 1920s, Jewish life in the city had also begun to fade.

Gainesville’s rise to economic prominence attracted growing numbers of fortune seekers, including Jews. As the frontier began to close around the turn of the 20th century, the small Jewish community of Gainesville experienced its heyday. United Hebrew Congregation, once located at the southeast corner of Broadway and Red River, had a thriving and active congregation within the confines of a small town whose population did not exceed 10,000 people until the 1950s.

Gainesville’s Jews played a leading role in the local dry goods industry as well as the liquor business and were deeply involved in civic life. However, the story of Jews in Gainesville follows the boomtown trend: while Jewish immigrants and migrants flocked to the area when the cattle industry thrived and business was good, a variety of factors caused business in Gainesville to dwindle. By the 1920s, Jewish life in the city had also begun to fade.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Gainesville

The Baum family. Photo

The Baum family. Photo courtesy of Erline Gordon.

Early Settlers

Jews began arriving in Gainesville in significant numbers during the 1870s. The extended family of Daniel and Bertha Baum was among these early settlers. Prussian-born Daniel had been a merchant in Corinth, Mississippi before moving his family to Gainesville by 1881. His brother Solomon and his family moved to town as well, as did Bertha’s brother Israel Cohen. Daniel and Solomon opened a dry goods store together in which Israel Cohen worked. Lambert Cahn moved to Gainesville from Louisiana with his family in the mid-1870s, working as a clerk in a store while his wife Annie worked as a milliner. Cahn later became a horse trader in Gainesville before leaving town in the 1890s. Aaron Goldstein lived in Gainesville with his wife Rosa by 1880 and owned a retail business. By 1887, he was a business partner of fellow Russian immigrant Gustave Melasky in a dry goods firm. Longtime residents the Schiff brothers, Gerson, Henry, and Jacob, each lived in Gainesville by 1880. Henry and Gerson initially owned a dry goods store in which Jacob worked. By 1900, Jacob was still a merchant, while Henry had become a grain dealer and Gerson a cotton buyer.

Jews began arriving in Gainesville in significant numbers during the 1870s. The extended family of Daniel and Bertha Baum was among these early settlers. Prussian-born Daniel had been a merchant in Corinth, Mississippi before moving his family to Gainesville by 1881. His brother Solomon and his family moved to town as well, as did Bertha’s brother Israel Cohen. Daniel and Solomon opened a dry goods store together in which Israel Cohen worked. Lambert Cahn moved to Gainesville from Louisiana with his family in the mid-1870s, working as a clerk in a store while his wife Annie worked as a milliner. Cahn later became a horse trader in Gainesville before leaving town in the 1890s. Aaron Goldstein lived in Gainesville with his wife Rosa by 1880 and owned a retail business. By 1887, he was a business partner of fellow Russian immigrant Gustave Melasky in a dry goods firm. Longtime residents the Schiff brothers, Gerson, Henry, and Jacob, each lived in Gainesville by 1880. Henry and Gerson initially owned a dry goods store in which Jacob worked. By 1900, Jacob was still a merchant, while Henry had become a grain dealer and Gerson a cotton buyer.

Organized Jewish Life in Gainesville

Not long after Jews settled in Gainesville, they began to organize. Local Jews established a Jewish cemetery association and a Hebrew Ladies Cemetery Society in 1877, though the earliest marked grave is that of Morris Kuehn, who died in 1881. Also in 1881, the Jews of Gainesville founded the United Hebrew Congregation and began to meet on the second floor of a downtown building. Daniel Baum was the congregation’s first president. Five years later, local women formed the Hebrew Ladies Aid Society and by 1888, the group, led by Annie Cahn, had 16 members. In 1888, the United Hebrew Congregation was meeting in a rented hall on East California Street. As suggested by its English name, United Hebrew Congregation was Reform, joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations by 1890 and installing an organ for use during services. In 1895, the congregation built a wood frame synagogue on East Broadway Street, remodeling it between 1909 and 1910. In a display of interfaith harmony, the congregation allowed the First Baptist Church to use the temple for Sunday services after their church was destroyed by fire in 1898. Similarly, the congregation allowed the Baptist Church to use the building for Sunday school in 1914. When the United Hebrew Congregation was no longer meeting regularly in 1918, they allowed the Seventh Day Adventist Church to use the temple free of charge.

By 1905, an estimated 180 Jews lived in Gainesville. This growing population led to the formation of other Jewish organizations. In the 1890s, Gainesville Jews founded a social organization, the Harmony Club, which met on the 3rd floor of the Metz Building. In 1904, eleven Gainesville women created a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women, though it disbanded in its first year. In 1901, 22 men established a lodge of B’nai B’rith which lasted a bit longer.

Despite its size, the United Hebrew Congregation occasionally employed full-time rabbis. According to the 1888 City Directory, Dr. Leon Strauss served as rabbi and ran the religious school. By 1895, H. Friedman led the congregation, serving until 1899. The 1895 Gainesville City Directory reports that, under the auspices of Rabbi Friedman, services were held on Friday nights and Saturday mornings. Perhaps due to Rabbi Friedman’s departure, no regular services were being held in 1900. In 1901, the congregation hired Rabbi Solomon Philo, who had answered their advertisement in the American Israelite newspaper. Rabbi Philo revived the Sunday school and produced an elaborate Hanukkah pageant, but he left Gainesville after only one year, taking a Reform pulpit in nearby Fort Worth.

Not long after Jews settled in Gainesville, they began to organize. Local Jews established a Jewish cemetery association and a Hebrew Ladies Cemetery Society in 1877, though the earliest marked grave is that of Morris Kuehn, who died in 1881. Also in 1881, the Jews of Gainesville founded the United Hebrew Congregation and began to meet on the second floor of a downtown building. Daniel Baum was the congregation’s first president. Five years later, local women formed the Hebrew Ladies Aid Society and by 1888, the group, led by Annie Cahn, had 16 members. In 1888, the United Hebrew Congregation was meeting in a rented hall on East California Street. As suggested by its English name, United Hebrew Congregation was Reform, joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations by 1890 and installing an organ for use during services. In 1895, the congregation built a wood frame synagogue on East Broadway Street, remodeling it between 1909 and 1910. In a display of interfaith harmony, the congregation allowed the First Baptist Church to use the temple for Sunday services after their church was destroyed by fire in 1898. Similarly, the congregation allowed the Baptist Church to use the building for Sunday school in 1914. When the United Hebrew Congregation was no longer meeting regularly in 1918, they allowed the Seventh Day Adventist Church to use the temple free of charge.

By 1905, an estimated 180 Jews lived in Gainesville. This growing population led to the formation of other Jewish organizations. In the 1890s, Gainesville Jews founded a social organization, the Harmony Club, which met on the 3rd floor of the Metz Building. In 1904, eleven Gainesville women created a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women, though it disbanded in its first year. In 1901, 22 men established a lodge of B’nai B’rith which lasted a bit longer.

Despite its size, the United Hebrew Congregation occasionally employed full-time rabbis. According to the 1888 City Directory, Dr. Leon Strauss served as rabbi and ran the religious school. By 1895, H. Friedman led the congregation, serving until 1899. The 1895 Gainesville City Directory reports that, under the auspices of Rabbi Friedman, services were held on Friday nights and Saturday mornings. Perhaps due to Rabbi Friedman’s departure, no regular services were being held in 1900. In 1901, the congregation hired Rabbi Solomon Philo, who had answered their advertisement in the American Israelite newspaper. Rabbi Philo revived the Sunday school and produced an elaborate Hanukkah pageant, but he left Gainesville after only one year, taking a Reform pulpit in nearby Fort Worth.

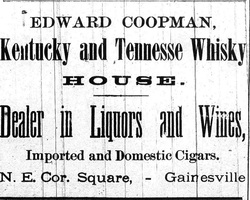

1890 ad for Edward Coopman's liquor business

1890 ad for Edward Coopman's liquor business

The United Hebrew Congregation reached its peak around the turn of the century, with 30 families in 1895 and 28 in 1900. However, shortly following its peak years, the congregation’s organization began to decline. Already by 1901 some Gainesville Jews were complaining about the apathy of congregation members. One reported in the Southwestern Jewish Sentiment in August 1901 that while in the past Gainesville Jews had been diligent about preserving their traditions and passing down Judaism to the next generation, "times have changed with the influx of so-called Jews whose only religion is their face, to whom the clink of the check and the dropping of the card is sweeter music than their child's voice in prayer, or in reciting the heroic deeds of our ancestors." In 1905, weekly Shabbat services were disbanded and while they had possibly been reinstated by 1907, by 1919 services were held only on Yom Kippur. Nonetheless, the temple maintained a small Sunday school that had 18 students. Despite this decline, the congregation remained active until the 1920s.

United Hebrew Congregation.

United Hebrew Congregation. Photo courtesy of Lary Kuehn.

The last 15 years of the United Hebrew Congregation are vividly depicted in their recently discovered minutes. The leadership of the congregation in 1905 consisted of Herman Scheline, president, Sam Kohn, vice president, Henry Schiff, treasurer, and S. Cohen, secretary. The minutes are devoted largely to the issue of acquiring rabbis for holiday services, suggesting that for many years in the early 20th century, the congregation did not have a full-time rabbi. The difficulty of finding a suitable rabbi dominated the congregation during these years. The near-constant debate about finding, approving, and paying for rabbinical services also helps us track the economic decline that lead to the end of the congregation and organized Jewish life in Gainesville.

The minutes of a meeting from June, 1905 indicated that Rabbi Alfred Godshaw of Cincinnati volunteered to conduct a confirmation service in Gainesville. In 1906, the congregation attempted to hire Rabbi G. Levy of Dallas and went so far as to document pledge amounts from the members of the congregation to pay the rabbi’s salary. However, the deal fell through and Rabbi Levy never occupied the Gainesville pulpit. In 1907, Rabbi Joseph Blatt of Oklahoma City offered to hold occasional Sunday services in Gainesville. The United Hebrew Congregation continued to bring in visiting rabbis for the High Holidays, although such arrangements did not always work out. In 1907, the congregation hired Rabbi S.S. Kohn of St. Louis to lead services on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. The congregation did not like the style of Kohn’s services, and called an emergency meeting on Rosh Hashanah morning, voting to send Rabbi Kohn home immediately “on [the] first train.” Rabbi George Zepin of Fort Worth's Beth-El congregation was hired by the congregation in 1908 to visit twice a month. In 1910, Zepin's replacement in Fort Worth, Rabbi George Fox, was hired to oversee the Sunday school and deliver two lectures per month. Rabbi Fox would return to Gainesville in 1918 to officiate at the wedding of Rose Baum, daughter of Daniel. In 1912, H.S. Scheline presided over services rather than a rabbi. The trend of laymen leading the services would continue, with Max Hirsch leading them in 1913. In 1914, Hebrew Union College offered to send down a rabbinic student, but the congregation turned the offer down due to a lack of funds. Lay member Sam Kohn led services for the congregation after 1915.

The minutes of a meeting from June, 1905 indicated that Rabbi Alfred Godshaw of Cincinnati volunteered to conduct a confirmation service in Gainesville. In 1906, the congregation attempted to hire Rabbi G. Levy of Dallas and went so far as to document pledge amounts from the members of the congregation to pay the rabbi’s salary. However, the deal fell through and Rabbi Levy never occupied the Gainesville pulpit. In 1907, Rabbi Joseph Blatt of Oklahoma City offered to hold occasional Sunday services in Gainesville. The United Hebrew Congregation continued to bring in visiting rabbis for the High Holidays, although such arrangements did not always work out. In 1907, the congregation hired Rabbi S.S. Kohn of St. Louis to lead services on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. The congregation did not like the style of Kohn’s services, and called an emergency meeting on Rosh Hashanah morning, voting to send Rabbi Kohn home immediately “on [the] first train.” Rabbi George Zepin of Fort Worth's Beth-El congregation was hired by the congregation in 1908 to visit twice a month. In 1910, Zepin's replacement in Fort Worth, Rabbi George Fox, was hired to oversee the Sunday school and deliver two lectures per month. Rabbi Fox would return to Gainesville in 1918 to officiate at the wedding of Rose Baum, daughter of Daniel. In 1912, H.S. Scheline presided over services rather than a rabbi. The trend of laymen leading the services would continue, with Max Hirsch leading them in 1913. In 1914, Hebrew Union College offered to send down a rabbinic student, but the congregation turned the offer down due to a lack of funds. Lay member Sam Kohn led services for the congregation after 1915.

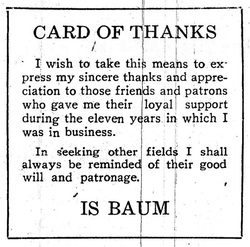

Leaving Gainesville, Isadore Baum, son of Daniel,

Leaving Gainesville, Isadore Baum, son of Daniel, thanks his customers in a 1920 ad.

Jewish Businesses in Gainesville

Jews in Gainesville were engaged in a variety of business ventures, though most owned retail stores. The cattle-herding consumers of Gainesville provided a unique customer base and there was profit to be made by anyone who could keep up with their needs. Memphis-born Leo Kuehn lived in Gainesville by 1890 and was the proprietor of Manhattan Clothiers, which remained in operation into the early 1920s. The store, located along California Street, was one of the town’s most prominent retail outlets. Kuehn had spent time in New York learning the clothing business from relatives. Kuehn, too, was heavily involved in the town’s civic life, serving as a founding member of the local Rotary Club in 1920.

Living in Gainesville by the turn of the century, German-born Herman Scheline owned a successful grocery store. He also served as treasurer of the Gainesville Street Fair Association and was a member of the local Knights of Pythias Lodge. Nathan Lapowski, a Russian immigrant, worked as a merchant and served with the Texas Volunteer Guard. Sigmond and Sefra Selton came to Gainesville in 1886 to join Sefra’s brother M. Whitesman, who was a tailor in town. Though Whitesman soon moved to Dallas, the Seltons opened a tailor shop and remained in Gainesville until 1919. John Cohn lived in Gainesville by 1910; a Russian immigrant, Cohn became a clothing merchant, opening the St. Louis Store by 1921.

A number of Gainesville Jews were involved in the liquor industry. By 1888, Lee Levy owned the St. James Saloon while William Schwarz owned the saloon in the Lindsay Hotel. A handful of other Jews, including Edward Coopman and L. Jacobs, owned wholesale liquor businesses as well as saloons. Henry Waterman and Charles Friedenheit opened a wholesale and retail liquor and tobacco business. By 1895, they owned the Kentucky Whiskey Depot. Though Jews are best remembered in Gainesville today as having been involved in the liquor business, they owned only a small percentage of the town’s saloons. In 1895, Jews owned five of the town’s 22 saloons. Nevertheless, the passage of local alcohol prohibition in 1910 is often credited with the sharp decline in Gainesville’s Jewish population soon thereafter.

Jews in Gainesville were engaged in a variety of business ventures, though most owned retail stores. The cattle-herding consumers of Gainesville provided a unique customer base and there was profit to be made by anyone who could keep up with their needs. Memphis-born Leo Kuehn lived in Gainesville by 1890 and was the proprietor of Manhattan Clothiers, which remained in operation into the early 1920s. The store, located along California Street, was one of the town’s most prominent retail outlets. Kuehn had spent time in New York learning the clothing business from relatives. Kuehn, too, was heavily involved in the town’s civic life, serving as a founding member of the local Rotary Club in 1920.

Living in Gainesville by the turn of the century, German-born Herman Scheline owned a successful grocery store. He also served as treasurer of the Gainesville Street Fair Association and was a member of the local Knights of Pythias Lodge. Nathan Lapowski, a Russian immigrant, worked as a merchant and served with the Texas Volunteer Guard. Sigmond and Sefra Selton came to Gainesville in 1886 to join Sefra’s brother M. Whitesman, who was a tailor in town. Though Whitesman soon moved to Dallas, the Seltons opened a tailor shop and remained in Gainesville until 1919. John Cohn lived in Gainesville by 1910; a Russian immigrant, Cohn became a clothing merchant, opening the St. Louis Store by 1921.

A number of Gainesville Jews were involved in the liquor industry. By 1888, Lee Levy owned the St. James Saloon while William Schwarz owned the saloon in the Lindsay Hotel. A handful of other Jews, including Edward Coopman and L. Jacobs, owned wholesale liquor businesses as well as saloons. Henry Waterman and Charles Friedenheit opened a wholesale and retail liquor and tobacco business. By 1895, they owned the Kentucky Whiskey Depot. Though Jews are best remembered in Gainesville today as having been involved in the liquor business, they owned only a small percentage of the town’s saloons. In 1895, Jews owned five of the town’s 22 saloons. Nevertheless, the passage of local alcohol prohibition in 1910 is often credited with the sharp decline in Gainesville’s Jewish population soon thereafter.

The Community Declines

By the early 1920s, the congregation had shrunk to the point where its future was in serious doubt. Many of its members had moved to nearby cities like Dallas, Ft. Worth, and Oklahoma City, seeking greater economic opportunity. The congregation’s minutes are filled with resolutions of appreciation for these departing members. In his 1913 letter stating the resignation of his membership, Jake Schiff wrote, noting the Temple’s declining membership: “I hope that in the near future you will gain as many members as we had in former years.” The United Hebrew Congregation’s reported membership dropped from 30 households in 1907 to 18, or possibly even fewer, in 1919. In 1920, the few remaining members of the congregation voted to sell the synagogue and its contents. The building and lot were sold in 1922 for $2,000, the transaction carried out by the last members of the now defunct congregation: Leo M. Keuhn, Max Hirsh, and M. Kahn. The remaining Jews of Gainesville would occasionally attend services just over the state-line in Ardmore, Oklahoma, 40 miles north. The Rosenstein family, who lived in Gainesville in the 1920s and 30s, sent their children to Temple Emanu-El in Dallas for Sunday school. In 1937, Gainesville’s Jewish population numbered just 13 people.

The reasons for the decline of Gainesville’s Jewish community are numerous. Certainly the passage of alcohol prohibition played a role, especially for those in the liquor business. Yet this decline had begun even before the law had passed. Larger economic forces and the general movement of Jewish merchants in the South were also crucial factors. As the frontier closed and the cattle industry declined, Gainesville lost much of its commercial potential. A declining customer base and overall economic decline drove many Jews to earn a living and practice their faith elsewhere.

By the early 1920s, the congregation had shrunk to the point where its future was in serious doubt. Many of its members had moved to nearby cities like Dallas, Ft. Worth, and Oklahoma City, seeking greater economic opportunity. The congregation’s minutes are filled with resolutions of appreciation for these departing members. In his 1913 letter stating the resignation of his membership, Jake Schiff wrote, noting the Temple’s declining membership: “I hope that in the near future you will gain as many members as we had in former years.” The United Hebrew Congregation’s reported membership dropped from 30 households in 1907 to 18, or possibly even fewer, in 1919. In 1920, the few remaining members of the congregation voted to sell the synagogue and its contents. The building and lot were sold in 1922 for $2,000, the transaction carried out by the last members of the now defunct congregation: Leo M. Keuhn, Max Hirsh, and M. Kahn. The remaining Jews of Gainesville would occasionally attend services just over the state-line in Ardmore, Oklahoma, 40 miles north. The Rosenstein family, who lived in Gainesville in the 1920s and 30s, sent their children to Temple Emanu-El in Dallas for Sunday school. In 1937, Gainesville’s Jewish population numbered just 13 people.

The reasons for the decline of Gainesville’s Jewish community are numerous. Certainly the passage of alcohol prohibition played a role, especially for those in the liquor business. Yet this decline had begun even before the law had passed. Larger economic forces and the general movement of Jewish merchants in the South were also crucial factors. As the frontier closed and the cattle industry declined, Gainesville lost much of its commercial potential. A declining customer base and overall economic decline drove many Jews to earn a living and practice their faith elsewhere.

The Jewish Community in Gainesville Today

Today, there is no Jewish community in Gainesville. The temple has been replaced by a parking lot, and few residents of the town would guess that there was ever a significant Jewish presence in the city of Gainesville.