Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Galveston, Texas

Galveston: Historical Overview

|

Driving down Broadway Avenue, one can see the splendors of Galveston’s past in the enormous Victorian homes that once housed the commercial magnates who transformed this small island into the largest city in Texas. Yet these historic homes also reflect a city whose peak was over a century ago. Ravaged by hurricanes and competition from nearby Houston, Galveston has survived largely on vacationers and tourists who flock to the island to enjoy its beaches and unique history. The Jews of Galveston have been an integral part of the city’s epic rise and decline. Arriving just as the town was laid out in 1838, they continue to maintain a vital presence today, though the Galveston Jewish community struggles with many of the same challenges faced by small Jewish communities across the South.

|

Galveston became one of the South's

Galveston became one of the South's largest ports in the late 19th century

In many ways, Galveston was inevitable. The island just off the coast of Texas was a natural port, attracting the Karankawa Indians and later the infamous pirate Jean Laffite, who set up his smuggling and privateering operation on the island in 1816. In 1838, Michel Menard bought over 4,000 acres next to the harbor and began to sell off plots of land, calling the town Galveston after the island and bay that had been named for Bernardo de Galvez, the 18th century viceroy of Mexico. By 1839, Galveston was officially chartered and quickly became the main port for the republic and later the state of Texas. As farmers and plantation owners grew more and more cotton, it was shipped out of the port of Galveston. Finished goods from Eastern markets and Europe came in through the port to be sold to Texas’ growing population. By 1860, Galveston was linked to the rest of Texas and the United States by a railroad bridge, easing the shipping of cotton and merchandise through the port city. Despite the hardships of the Civil War and yellow fever, Galveston grew to become the biggest city in Texas, with almost 14,000 residents in 1870.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Galveston

Rosanna Osterman

Rosanna Osterman

Early Settlers

A handful of Jewish immigrants who saw tremendous economic potential in the burgeoning port city were among the earliest settlers in Galveston. Joseph Osterman, a Dutch native, moved to Galveston from Baltimore in 1838 after a doctor recommended a warmer climate for his wife Rosanna, who had a heart condition. Osterman became one of the first merchants to set up shop in the new town, and quickly amassed a significant fortune through the cotton trade. Rosanna had a strong business acumen and helped him run the store. After only a few years, Osterman sold his store, then the largest in town, to his brother-in-law Isadore Dyer, and focused on real estate ventures. By 1860, Osterman was worth $191,000. When the city government had trouble paying its debts in its early years, Osterman would often lend it money.

These early Jews were closely involved in civic affairs. Michael Seeligson, who also came to Galveston in 1838, quickly became a town alderman and was elected mayor in 1853. In a letter to the national Jewish newspaper, the Occident, Seeligson explained that he ran for mayor to “thwart the designs of certain clique” who had been speaking out publicly against Jews. Seeligson’s comments indicate that while there was a degree of anti-Semitism in Galveston during these early years, the town’s Jews were willing and able to confront and defeat it. Seeligson was not the only officeholder among these early Jewish settlers. Isadore Dyer served as an alderman in the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s.

A handful of Jewish immigrants who saw tremendous economic potential in the burgeoning port city were among the earliest settlers in Galveston. Joseph Osterman, a Dutch native, moved to Galveston from Baltimore in 1838 after a doctor recommended a warmer climate for his wife Rosanna, who had a heart condition. Osterman became one of the first merchants to set up shop in the new town, and quickly amassed a significant fortune through the cotton trade. Rosanna had a strong business acumen and helped him run the store. After only a few years, Osterman sold his store, then the largest in town, to his brother-in-law Isadore Dyer, and focused on real estate ventures. By 1860, Osterman was worth $191,000. When the city government had trouble paying its debts in its early years, Osterman would often lend it money.

These early Jews were closely involved in civic affairs. Michael Seeligson, who also came to Galveston in 1838, quickly became a town alderman and was elected mayor in 1853. In a letter to the national Jewish newspaper, the Occident, Seeligson explained that he ran for mayor to “thwart the designs of certain clique” who had been speaking out publicly against Jews. Seeligson’s comments indicate that while there was a degree of anti-Semitism in Galveston during these early years, the town’s Jews were willing and able to confront and defeat it. Seeligson was not the only officeholder among these early Jewish settlers. Isadore Dyer served as an alderman in the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s.

Hebrew Benevolent Society cemetery

Hebrew Benevolent Society cemetery

Organized Jewish Life in Galveston

While a growing number of Jews moved to Galveston during the 1840s and 50s, they were slow to establish Jewish institutions and often struggled to maintain their religious traditions. In 1852, one local Jew reported to the Occident that E. Cohen chose to circumcise his own son since he was unable to bring in a mohel from New Orleans to perform the ritual. A local surgeon supervised as the untrained Cohen performed the procedure. That same year, Galveston Jews dedicated their first cemetery, bringing in Rev. M.N. Nathan from a New Orleans synagogue to lead the ceremony. Although according to the local newspaper there were not enough Jews in Galveston to support a congregation, Rev. Nathan chided Galveston Jews during his remarks for neglecting their religious traditions and even attending Christian churches. Nathan admitted that while they were too small in number to build a synagogue, “you can pray at home, instead of inconsistently going with your families to church and chapel to pray to a mediator who no instructed Israelite believes in and listen to dogmas and doctrine to which you cannot subscribe.” Despite Nathan’s entreaties, Galveston Jews did not hold religious services until 1856, when they prayed together in the home of Isadore Dyer. By 1859, they were meeting for the High Holidays.

The progress of the Galveston Jewish community was interrupted by the Civil War. When the Union military captured the city early in the conflict, most Galveston Jews moved to Houston, while others went to Matamoros, Mexico, where they were able to ship cotton through the Union blockade. Rosanna Osterman, whose husband Joseph had died in 1861, remained in Galveston during the war, nursing the wounded of both sides in her home. According to legend, Osterman overheard crucial troop information while nursing Union soldiers, and shared it with the Confederate forces, enabling them to retake the city in early 1863. Nevertheless, the Union continued its blockade of the port, as business in the city suffered severely during the war.

Rosanna Osterman was dedicated to building the local Jewish community. After she died tragically in a steamboat explosion in 1866, her will provided money to start various Jewish organizations in Galveston. Her bequests included money to buy additional land for a cemetery, $1,000 for a Jewish Benevolent Society, which had not yet been founded, $1,000 for a Jewish school in Galveston, and $5,000 to go toward construction of a synagogue. Osterman also left money to the state’s only chartered congregation, Beth Israel in Houston, as well as to Jewish organizations and charities around the country. Through her will, Osterman was able to jumpstart the Galveston Jewish community after decades of lethargy.

With Osterman’s money as the impetus, eight Galveston Jews established a benevolent society in 1866 and soon discussed forming a congregation. A local Gentile butcher began to supply kosher meat to the Jewish community. All of the founding members of the Hebrew Benevolent Society were merchants, while most were young. Only one, Isadore Dyer, was over 35 years old. All but one was foreign-born, with most from Alsace and the German states. Only two of the eight were listed as living in Galveston in the 1860 census. The local newspaper praised the creation of the benevolent society, but called on Galveston Jews to go further and construct a house of worship, arguing that if they were religiously observant Jews, they would be better citizens and would help uplift the entire community.

This development was slowed by a major yellow fever outbreak in 1867, which killed as many as 40 Jews in the area, forcing Galveston Jews to buy land for a new cemetery. Isadore Dyer, president of the Hebrew Benevolent Society, made an appeal for financial help in the Occident newspaper since the society had already spent all of its money helping the sick and burying the Jewish dead. Despite this setback, the Jewish community moved forward as external pressure, Osterman’s financial largesse, and the growing size and wealth of the Galveston Jewish population finally led to the formation of Congregation B’nai Israel in 1868 and the construction of a grand synagogue in 1870.

While a growing number of Jews moved to Galveston during the 1840s and 50s, they were slow to establish Jewish institutions and often struggled to maintain their religious traditions. In 1852, one local Jew reported to the Occident that E. Cohen chose to circumcise his own son since he was unable to bring in a mohel from New Orleans to perform the ritual. A local surgeon supervised as the untrained Cohen performed the procedure. That same year, Galveston Jews dedicated their first cemetery, bringing in Rev. M.N. Nathan from a New Orleans synagogue to lead the ceremony. Although according to the local newspaper there were not enough Jews in Galveston to support a congregation, Rev. Nathan chided Galveston Jews during his remarks for neglecting their religious traditions and even attending Christian churches. Nathan admitted that while they were too small in number to build a synagogue, “you can pray at home, instead of inconsistently going with your families to church and chapel to pray to a mediator who no instructed Israelite believes in and listen to dogmas and doctrine to which you cannot subscribe.” Despite Nathan’s entreaties, Galveston Jews did not hold religious services until 1856, when they prayed together in the home of Isadore Dyer. By 1859, they were meeting for the High Holidays.

The progress of the Galveston Jewish community was interrupted by the Civil War. When the Union military captured the city early in the conflict, most Galveston Jews moved to Houston, while others went to Matamoros, Mexico, where they were able to ship cotton through the Union blockade. Rosanna Osterman, whose husband Joseph had died in 1861, remained in Galveston during the war, nursing the wounded of both sides in her home. According to legend, Osterman overheard crucial troop information while nursing Union soldiers, and shared it with the Confederate forces, enabling them to retake the city in early 1863. Nevertheless, the Union continued its blockade of the port, as business in the city suffered severely during the war.

Rosanna Osterman was dedicated to building the local Jewish community. After she died tragically in a steamboat explosion in 1866, her will provided money to start various Jewish organizations in Galveston. Her bequests included money to buy additional land for a cemetery, $1,000 for a Jewish Benevolent Society, which had not yet been founded, $1,000 for a Jewish school in Galveston, and $5,000 to go toward construction of a synagogue. Osterman also left money to the state’s only chartered congregation, Beth Israel in Houston, as well as to Jewish organizations and charities around the country. Through her will, Osterman was able to jumpstart the Galveston Jewish community after decades of lethargy.

With Osterman’s money as the impetus, eight Galveston Jews established a benevolent society in 1866 and soon discussed forming a congregation. A local Gentile butcher began to supply kosher meat to the Jewish community. All of the founding members of the Hebrew Benevolent Society were merchants, while most were young. Only one, Isadore Dyer, was over 35 years old. All but one was foreign-born, with most from Alsace and the German states. Only two of the eight were listed as living in Galveston in the 1860 census. The local newspaper praised the creation of the benevolent society, but called on Galveston Jews to go further and construct a house of worship, arguing that if they were religiously observant Jews, they would be better citizens and would help uplift the entire community.

This development was slowed by a major yellow fever outbreak in 1867, which killed as many as 40 Jews in the area, forcing Galveston Jews to buy land for a new cemetery. Isadore Dyer, president of the Hebrew Benevolent Society, made an appeal for financial help in the Occident newspaper since the society had already spent all of its money helping the sick and burying the Jewish dead. Despite this setback, the Jewish community moved forward as external pressure, Osterman’s financial largesse, and the growing size and wealth of the Galveston Jewish population finally led to the formation of Congregation B’nai Israel in 1868 and the construction of a grand synagogue in 1870.

The Community Grows

After the Civil War, business as usual was restored in Galveston and a growing number of Jews from Alsace, Germany, and Poland came to the port city to seek their fortunes. By 1868, an estimated 125 Jews lived on the island. Leon Blum left Alsace in 1852 and spent the first 18 months in the U.S. as a traveling peddler in rural Louisiana. He came to Galveston with his older brother Alexander in 1859, but fled the city after the start of the war, moving their business to Houston and later Matamoros, Mexico. Right after the war, the Blums returned to Galveston and opened a wholesale dry goods house, which became a quick success. In 1870, the firm did over $1 million in business; that same year the Leon & H. Blum Company opened a huge new building on the downtown Strand. By 1883, Leon Blum’s wholesale business was one of the leading wholesale houses in the South, employing 200 people. Blum became one of Galveston’s business titans. A member of the Cotton Exchange, Blum led the effort to construct a grand building for the organization. He worked to improve the city’s port and its rail links to the Texas interior, helping to found the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railroad. Blum also established the People’s Street Railway, a public transportation system that was later absorbed by the city.

Blum was just one of a number of prominent Jewish business magnates who helped to make Galveston the economic and cultural center of the southwest in the late 19th century. Moritz Kopperl came to Galveston in 1857, but especially thrived in the post-war period, establishing a successful cotton commission and coffee importation business. In 1868, Kopperl became president of the National Bank of Texas; nine years later he was president of the Gulf, Colorado, and Santa Fe Railroad. Following the pattern set by the earliest Jewish settlers in Galveston, Kopperl became an important civic leader, serving as a city alderman before being elected to the state legislature in 1876. He was also very philanthropic, supporting the local Protestant Orphans Home, which named the Kopperl Infirmary in his honor.

The Jewish family that had perhaps the most lasting impact on the island was the Kempners. Polish-born Harris Kempner came to the U.S. in 1854, settling initially in Cold Springs, Texas, where he worked as a peddler. After fighting for the Confederacy, Kempner moved to Galveston in 1870, opening a wholesale grocery and liquor business with partner Max Marx. According to a Galveston Business Review published in 1884, Marx & Kempner had built up “a colossal trade, whose ramifications extend beyond the confines of Texas, and reach into the land of the Montezumas.” In 1885, Kempner became president of the Island City Savings Bank. Kempner was also a cotton factor; when he died in 1894, he was one of the largest cotton dealers in Texas and left an estate worth $1.25 million. His wife Eliza was very active in local charities, spending 50 years on the board of the Galveston Orphans Home. She also donated a house to B’nai Israel, which was used as a parsonage for the rabbi. After Harris’ death, their son Isaac Harris Kempner took over the family operation, which included a wide array of businesses, including railroads, insurance, ranching, oil, real estate, and cotton. In 1902, Kempner bought Island City Savings Bank, later changing its name to the Texas Bank & Trust Company. He also served as president of the Galveston Cotton Exchange. In 1907, he bought a regional sugar company, renaming it Imperial Sugar.

Several other Jews opened successful businesses in Galveston in the years after the Civil War. Felix Halff moved to the city just after the war ended, starting a wholesale dry goods firm. In 1872, he opened a high-end clothing store with Albert Weis on the Strand. Brothers Joseph and Ben Levy started a livery and undertaking business that remained in operation for over a century. Their sons later took over the business. Joseph’s grandson, Joe Levy, ran the funeral home from 1930 until he sold it in 1969. When newspaper editor Charles Wessolowsky visited Galveston in 1879, he noted how many Jews owned large commercial firms, declaring that such a number “are seldom to be found in any city in the South.” Wessolowsky claimed that “our Israelitish brethren are adding vastly to the progress, advancement and promotion of the city.”

After the Civil War, business as usual was restored in Galveston and a growing number of Jews from Alsace, Germany, and Poland came to the port city to seek their fortunes. By 1868, an estimated 125 Jews lived on the island. Leon Blum left Alsace in 1852 and spent the first 18 months in the U.S. as a traveling peddler in rural Louisiana. He came to Galveston with his older brother Alexander in 1859, but fled the city after the start of the war, moving their business to Houston and later Matamoros, Mexico. Right after the war, the Blums returned to Galveston and opened a wholesale dry goods house, which became a quick success. In 1870, the firm did over $1 million in business; that same year the Leon & H. Blum Company opened a huge new building on the downtown Strand. By 1883, Leon Blum’s wholesale business was one of the leading wholesale houses in the South, employing 200 people. Blum became one of Galveston’s business titans. A member of the Cotton Exchange, Blum led the effort to construct a grand building for the organization. He worked to improve the city’s port and its rail links to the Texas interior, helping to found the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railroad. Blum also established the People’s Street Railway, a public transportation system that was later absorbed by the city.

Blum was just one of a number of prominent Jewish business magnates who helped to make Galveston the economic and cultural center of the southwest in the late 19th century. Moritz Kopperl came to Galveston in 1857, but especially thrived in the post-war period, establishing a successful cotton commission and coffee importation business. In 1868, Kopperl became president of the National Bank of Texas; nine years later he was president of the Gulf, Colorado, and Santa Fe Railroad. Following the pattern set by the earliest Jewish settlers in Galveston, Kopperl became an important civic leader, serving as a city alderman before being elected to the state legislature in 1876. He was also very philanthropic, supporting the local Protestant Orphans Home, which named the Kopperl Infirmary in his honor.

The Jewish family that had perhaps the most lasting impact on the island was the Kempners. Polish-born Harris Kempner came to the U.S. in 1854, settling initially in Cold Springs, Texas, where he worked as a peddler. After fighting for the Confederacy, Kempner moved to Galveston in 1870, opening a wholesale grocery and liquor business with partner Max Marx. According to a Galveston Business Review published in 1884, Marx & Kempner had built up “a colossal trade, whose ramifications extend beyond the confines of Texas, and reach into the land of the Montezumas.” In 1885, Kempner became president of the Island City Savings Bank. Kempner was also a cotton factor; when he died in 1894, he was one of the largest cotton dealers in Texas and left an estate worth $1.25 million. His wife Eliza was very active in local charities, spending 50 years on the board of the Galveston Orphans Home. She also donated a house to B’nai Israel, which was used as a parsonage for the rabbi. After Harris’ death, their son Isaac Harris Kempner took over the family operation, which included a wide array of businesses, including railroads, insurance, ranching, oil, real estate, and cotton. In 1902, Kempner bought Island City Savings Bank, later changing its name to the Texas Bank & Trust Company. He also served as president of the Galveston Cotton Exchange. In 1907, he bought a regional sugar company, renaming it Imperial Sugar.

Several other Jews opened successful businesses in Galveston in the years after the Civil War. Felix Halff moved to the city just after the war ended, starting a wholesale dry goods firm. In 1872, he opened a high-end clothing store with Albert Weis on the Strand. Brothers Joseph and Ben Levy started a livery and undertaking business that remained in operation for over a century. Their sons later took over the business. Joseph’s grandson, Joe Levy, ran the funeral home from 1930 until he sold it in 1969. When newspaper editor Charles Wessolowsky visited Galveston in 1879, he noted how many Jews owned large commercial firms, declaring that such a number “are seldom to be found in any city in the South.” Wessolowsky claimed that “our Israelitish brethren are adding vastly to the progress, advancement and promotion of the city.”

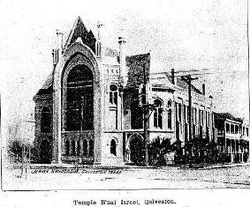

B'nai Israel's first synagogue, completed in 1870.

B'nai Israel's first synagogue, completed in 1870.

B'nai Israel

From its founding in 1868, B’nai Israel was a Reform congregation, befitting the cultural assimilation and German heritage of its members. Soon after they organized, the members hired Alexander Rosenpitz as their first spiritual leader. In 1870, the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society was created; Caroline Block was its first president, serving 30 years in the position. In 1871, B’nai Israel hired its first ordained rabbi, Abraham Blum, who led the island congregation for the next 14 years. During his tenure as rabbi, Blum received a degree from the local medical college and became a member of the State Medical Association of Texas. Blum took part in a statewide circuit-riding rabbi program, visiting small Jewish communities throughout Texas. Rabbi Blum was able to help start religious schools in Brenham, Waco, Fort Worth, and Brownsville. B’nai Israel was relatively small but had lots of young families. In 1880, the congregation had 61 member households, but 188 students in their religious school.

The course of B’nai Israel and the Galveston Jewish community was forever changed when the young rabbi Henry Cohen arrived on the island in 1888. For the next 64 years Cohen put his indelible stamp on B’nai Israel and set a remarkable standard for rabbinic involvement in the larger community. Rabbi Cohen was a strong advocate for prison reform, serving on the Texas Board of Pardons and working to rehabilitate released prisoners. After the great hurricane of 1900, Rabbi Cohen helped to maintain order in the city and organized a central executive relief commission. According to local legend, Cohen, along with his close friend Father Kirwin of the Catholic diocese, prevented the Ku Klux Klan from marching on the island by blocking them on the causeway bridge. When Cohen learned that the U.S. Navy had no Jewish chaplains during World War I, he lobbied successfully to get special legislation allowing for rabbis to serve as Navy chaplains. President Woodrow Wilson sent Cohen the pen with which he signed the bill into law. An obituary that ran in the Associated Press described Cohen as “one of the greatest crusaders and inspirational and spiritual leaders in Texas history.” According to the historian Jacob Rader Marcus, Cohen was “a pastor whose field was not the small confines of the Jewish parish but the entire community of which he became the throbbing heartbeat.”

From its founding in 1868, B’nai Israel was a Reform congregation, befitting the cultural assimilation and German heritage of its members. Soon after they organized, the members hired Alexander Rosenpitz as their first spiritual leader. In 1870, the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society was created; Caroline Block was its first president, serving 30 years in the position. In 1871, B’nai Israel hired its first ordained rabbi, Abraham Blum, who led the island congregation for the next 14 years. During his tenure as rabbi, Blum received a degree from the local medical college and became a member of the State Medical Association of Texas. Blum took part in a statewide circuit-riding rabbi program, visiting small Jewish communities throughout Texas. Rabbi Blum was able to help start religious schools in Brenham, Waco, Fort Worth, and Brownsville. B’nai Israel was relatively small but had lots of young families. In 1880, the congregation had 61 member households, but 188 students in their religious school.

The course of B’nai Israel and the Galveston Jewish community was forever changed when the young rabbi Henry Cohen arrived on the island in 1888. For the next 64 years Cohen put his indelible stamp on B’nai Israel and set a remarkable standard for rabbinic involvement in the larger community. Rabbi Cohen was a strong advocate for prison reform, serving on the Texas Board of Pardons and working to rehabilitate released prisoners. After the great hurricane of 1900, Rabbi Cohen helped to maintain order in the city and organized a central executive relief commission. According to local legend, Cohen, along with his close friend Father Kirwin of the Catholic diocese, prevented the Ku Klux Klan from marching on the island by blocking them on the causeway bridge. When Cohen learned that the U.S. Navy had no Jewish chaplains during World War I, he lobbied successfully to get special legislation allowing for rabbis to serve as Navy chaplains. President Woodrow Wilson sent Cohen the pen with which he signed the bill into law. An obituary that ran in the Associated Press described Cohen as “one of the greatest crusaders and inspirational and spiritual leaders in Texas history.” According to the historian Jacob Rader Marcus, Cohen was “a pastor whose field was not the small confines of the Jewish parish but the entire community of which he became the throbbing heartbeat.”

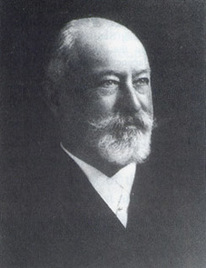

Leo N. Levi

Leo N. Levi

Leo N. Levi

Rabbi Cohen was not the only Galveston Jew to play a role on the national political stage. Leo N. Levi, a native of Victoria, Texas, moved to Galveston after graduating from the University of Virginia in 1876. Levi became active in the local B’nai B’rith lodge, which had been established in 1874. He also served as president of B’nai Israel from 1887 to 1899. In 1900, Levi moved to New York to become the national president of B’nai B’rith. Levi lobbied the government to do something about anti-Semitic laws in Romania and Russia and drafted the protest petition sent to the czar by President Theodore Roosevelt after the Kishnieff Pogrom. After Levi died in 1904 at age 47, B’nai B’rith named a hospital and rehab center after him in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Rabbi Cohen was not the only Galveston Jew to play a role on the national political stage. Leo N. Levi, a native of Victoria, Texas, moved to Galveston after graduating from the University of Virginia in 1876. Levi became active in the local B’nai B’rith lodge, which had been established in 1874. He also served as president of B’nai Israel from 1887 to 1899. In 1900, Levi moved to New York to become the national president of B’nai B’rith. Levi lobbied the government to do something about anti-Semitic laws in Romania and Russia and drafted the protest petition sent to the czar by President Theodore Roosevelt after the Kishnieff Pogrom. After Levi died in 1904 at age 47, B’nai B’rith named a hospital and rehab center after him in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

The 1900 Hurricane

Located on an island in the Gulf of Mexico, Galveston has often found itself in the path of hurricanes. In 1900, the city was struck by a tremendous storm that helped end Galveston’s prominent role in the state’s economy. The hurricane killed between 6,000 and 8,000 people and caused over $20 million in damage. As community leaders, prominent Jews played a big role in the rebuilding effort. I.H. Kempner gave interest-free loans to B’nai Israel, several local churches, the library, and the local orphans home to help them get back on their feet after the storm. In 1901, Kempner became Galveston’s first finance commissioner and helped the city regain its economic footing. Despite the work of Kempner and Rabbi Cohen, Galveston would never be the same after the storm. With the rise of industrial and railroad centers like Dallas, Galveston had already slipped to being only the 4th largest city in the state by the time of the storm. With Galveston devastated by the hurricane, nearby Houston moved forward with its plan to build a ship channel from the Gulf, completing it in 1914. The Port of Houston soon outstripped Galveston, eventually becoming the second busiest port in the country. By 1980, Galveston was only the 25th largest city in the state, with its economy based largely on tourism.

Located on an island in the Gulf of Mexico, Galveston has often found itself in the path of hurricanes. In 1900, the city was struck by a tremendous storm that helped end Galveston’s prominent role in the state’s economy. The hurricane killed between 6,000 and 8,000 people and caused over $20 million in damage. As community leaders, prominent Jews played a big role in the rebuilding effort. I.H. Kempner gave interest-free loans to B’nai Israel, several local churches, the library, and the local orphans home to help them get back on their feet after the storm. In 1901, Kempner became Galveston’s first finance commissioner and helped the city regain its economic footing. Despite the work of Kempner and Rabbi Cohen, Galveston would never be the same after the storm. With the rise of industrial and railroad centers like Dallas, Galveston had already slipped to being only the 4th largest city in the state by the time of the storm. With Galveston devastated by the hurricane, nearby Houston moved forward with its plan to build a ship channel from the Gulf, completing it in 1914. The Port of Houston soon outstripped Galveston, eventually becoming the second busiest port in the country. By 1980, Galveston was only the 25th largest city in the state, with its economy based largely on tourism.

|

Multimedia: Dr. Aaron Kreisler of Dallas contrasts Reform Rabbi Henry Cohen of Galveston with his Orthodox counterpart, Rabbi Louis Feigon. Dr. Kreisler grew up in Galveston, where his parents settled after fleeing Poland in the late 1930s. "The Bishop" Kreisler mentions is most likely Father James M. Kirwin

|

|

Jacob Schiff, architect and

Jacob Schiff, architect and founder of the Galveston Movement

The Early 20th Century

Despite this impact on Galveston’s economy, the city remained a port of arrival for many European immigrants in the early 20th century. While Galveston paled in comparison to the great east coast immigration ports like New York and Baltimore, one effort sought to transform Jewish settlement in America by encouraging immigration through the Texas port. National Jewish leaders like Jacob Schiff worried that the growing number of poor Jewish immigrants concentrating in Northern cities like New York would lead to calls to restrict Jewish immigration to the United States. Schiff’s plan was to disperse these newly arriving Jews more evenly throughout the country by encouraging them to come through the port of Galveston instead of New York. Galveston was selected because it was a western terminus of several railroads, had Rabbi Henry Cohen, and because the city was too small to entice many immigrants to remain there. Instead, the immigrants would be placed on a train heading to another town in Texas or the Midwest, where they would be given a job and a place to live initially. During the brief time they were in Galveston, the immigrants were often visited by Rabbi Cohen, who could serve as a Yiddish translator. This so-called “Galveston Movement” ran from 1907 to 1914, and as an effort to transform Jewish immigration patterns, was a failure. All told, about 10,000 Jewish immigrants came to Galveston under its auspices. Most all of them did not remain on the island, though 25% ended up settling elsewhere in Texas, the most of any state.

Despite this impact on Galveston’s economy, the city remained a port of arrival for many European immigrants in the early 20th century. While Galveston paled in comparison to the great east coast immigration ports like New York and Baltimore, one effort sought to transform Jewish settlement in America by encouraging immigration through the Texas port. National Jewish leaders like Jacob Schiff worried that the growing number of poor Jewish immigrants concentrating in Northern cities like New York would lead to calls to restrict Jewish immigration to the United States. Schiff’s plan was to disperse these newly arriving Jews more evenly throughout the country by encouraging them to come through the port of Galveston instead of New York. Galveston was selected because it was a western terminus of several railroads, had Rabbi Henry Cohen, and because the city was too small to entice many immigrants to remain there. Instead, the immigrants would be placed on a train heading to another town in Texas or the Midwest, where they would be given a job and a place to live initially. During the brief time they were in Galveston, the immigrants were often visited by Rabbi Cohen, who could serve as a Yiddish translator. This so-called “Galveston Movement” ran from 1907 to 1914, and as an effort to transform Jewish immigration patterns, was a failure. All told, about 10,000 Jewish immigrants came to Galveston under its auspices. Most all of them did not remain on the island, though 25% ended up settling elsewhere in Texas, the most of any state.

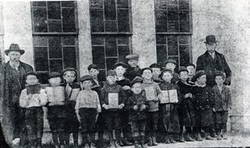

Orthodox Hebrew School, circa 1903

Orthodox Hebrew School, circa 1903

Orthodox Jews in Galveston

The first Jews to live in Galveston were from Alsace and the German states. By the late 19th century, another wave of Jewish immigrants began to settle on the island. Desiring a more Orthodox religious practice, these Eastern European immigrants established their own congregations with the encouragement of the Reform B’nai Israel. In 1888, B’nai Israel lent a Torah to group of Russian Jews who had begun to pray together in Galveston. In 1894 they established a Young Men’s Hebrew Association with the express purpose of creating a place for poorer Orthodox immigrants to worship. In 1895, the group formally established their own congregation, known initially as Ahavas Israel. The Orthodox congregation hired Jacob Geller as their rabbi by 1900; they constructed a synagogue in 1905 on Avenue I between 26th and 27th streets. By 1907, Ahavas Israel had 60 members and daily services and a Hebrew school led by Rabbi Geller.

In 1905, there was a split within Galveston’s Orthodox community, with Jews from the Austro-Hungarian Empire forming their own separate congregation. It’s unclear what exactly caused the split, but differences in minhag (religious customs) along with disagreements over the certification of kosher food likely played an important part. One group, made up primarily of Russian Jews, became known as the Young Men’s Hebrew Association and continued worshiping in the Avenue I synagogue. The other, made up of immigrants from Galicia and Austria, created the Hebrew Orthodox Benevolent Association, which met at a building on Avenue H. During these early years, Rabbi Geller led the Austrian shul, while Abraham Gordon led the Russian congregation. Both were shochets (kosher meat slaughterers) and had a hard time earning a living providing kosher meat to the Galveston Orthodox community. After Gordon left for Fort Worth, Geller would lead services at both congregations for the High Holidays before he too moved away in 1910. The rift between these two Orthodox congregations was often bitter and personal. It would be a quarter of a century before Galveston’s Orthodox Jews reunited.

While the island’s two Orthodox congregations did not get along, they seemed to have cordial relations with the much larger and wealthier B’nai Israel. For many years, Orthodox children attended Sunday school at the Reform temple. Rabbi Cohen fought to ensure that their families did not have to pay to send their children to the Sunday school, fearing that they would not be willing to support the temple financially. Cohen wanted to ensure that these young people received instruction in the tenets of their religion, in addition to the Hebrew language lessons they learned in their own congregations’ weekday Hebrew schools. In 1917, of the 200 children in the B’nai Israel Sunday school, about 160 were from the Orthodox community. In 1919, Galveston’s Orthodox Jews finally created their own religious school.

The first Jews to live in Galveston were from Alsace and the German states. By the late 19th century, another wave of Jewish immigrants began to settle on the island. Desiring a more Orthodox religious practice, these Eastern European immigrants established their own congregations with the encouragement of the Reform B’nai Israel. In 1888, B’nai Israel lent a Torah to group of Russian Jews who had begun to pray together in Galveston. In 1894 they established a Young Men’s Hebrew Association with the express purpose of creating a place for poorer Orthodox immigrants to worship. In 1895, the group formally established their own congregation, known initially as Ahavas Israel. The Orthodox congregation hired Jacob Geller as their rabbi by 1900; they constructed a synagogue in 1905 on Avenue I between 26th and 27th streets. By 1907, Ahavas Israel had 60 members and daily services and a Hebrew school led by Rabbi Geller.

In 1905, there was a split within Galveston’s Orthodox community, with Jews from the Austro-Hungarian Empire forming their own separate congregation. It’s unclear what exactly caused the split, but differences in minhag (religious customs) along with disagreements over the certification of kosher food likely played an important part. One group, made up primarily of Russian Jews, became known as the Young Men’s Hebrew Association and continued worshiping in the Avenue I synagogue. The other, made up of immigrants from Galicia and Austria, created the Hebrew Orthodox Benevolent Association, which met at a building on Avenue H. During these early years, Rabbi Geller led the Austrian shul, while Abraham Gordon led the Russian congregation. Both were shochets (kosher meat slaughterers) and had a hard time earning a living providing kosher meat to the Galveston Orthodox community. After Gordon left for Fort Worth, Geller would lead services at both congregations for the High Holidays before he too moved away in 1910. The rift between these two Orthodox congregations was often bitter and personal. It would be a quarter of a century before Galveston’s Orthodox Jews reunited.

While the island’s two Orthodox congregations did not get along, they seemed to have cordial relations with the much larger and wealthier B’nai Israel. For many years, Orthodox children attended Sunday school at the Reform temple. Rabbi Cohen fought to ensure that their families did not have to pay to send their children to the Sunday school, fearing that they would not be willing to support the temple financially. Cohen wanted to ensure that these young people received instruction in the tenets of their religion, in addition to the Hebrew language lessons they learned in their own congregations’ weekday Hebrew schools. In 1917, of the 200 children in the B’nai Israel Sunday school, about 160 were from the Orthodox community. In 1919, Galveston’s Orthodox Jews finally created their own religious school.

Beth Jacob's synagogue, constructed in 1932.

Beth Jacob's synagogue, constructed in 1932.

Jewish Organizations in Galveston

While they were divided in their religious worship, Galveston’s Eastern European immigrants came together to support larger Jewish causes. In 1898 they founded the B’nai Zion organization which worked to create a Jewish homeland in Palestine. While the Zionist movement was never particularly strong in the city, Galveston Jews were able to raise a significant amount of money to support the Jewish settlement in Palestine. Women later established a Hadassah chapter on the island. In 1952, Etta Lasker Rosensohn of Galveston became the national president of Hadassah, the first Texan to hold this position. Rosensohn also served on the board of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Eastern European Jews founded a Galveston branch of the socialist Workmen’s Circle in 1912. Frieda Weiner, who came to the island in 1915, was a longtime leader of the group, which advocated Yiddish culture and working class politics. Weiner later founded a chapter of Pioneer Women, a labor Zionist organization, and served as its president for 30 years.

By 1907, approximately 1000 Jews lived in Galveston. For the next half century, the Jewish population on the island remained on a plateau, reaching 1200 people in 1937. Nevertheless, B’nai Israel enjoyed a period of growth in the first half of the 20th century, increasing its membership from 150 dues paying families in 1910 to 190 in 1930. In 1928, the congregation added a community house, named after Henry Cohen, next to their synagogue which included new classrooms and an auditorium

While they were divided in their religious worship, Galveston’s Eastern European immigrants came together to support larger Jewish causes. In 1898 they founded the B’nai Zion organization which worked to create a Jewish homeland in Palestine. While the Zionist movement was never particularly strong in the city, Galveston Jews were able to raise a significant amount of money to support the Jewish settlement in Palestine. Women later established a Hadassah chapter on the island. In 1952, Etta Lasker Rosensohn of Galveston became the national president of Hadassah, the first Texan to hold this position. Rosensohn also served on the board of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Eastern European Jews founded a Galveston branch of the socialist Workmen’s Circle in 1912. Frieda Weiner, who came to the island in 1915, was a longtime leader of the group, which advocated Yiddish culture and working class politics. Weiner later founded a chapter of Pioneer Women, a labor Zionist organization, and served as its president for 30 years.

By 1907, approximately 1000 Jews lived in Galveston. For the next half century, the Jewish population on the island remained on a plateau, reaching 1200 people in 1937. Nevertheless, B’nai Israel enjoyed a period of growth in the first half of the 20th century, increasing its membership from 150 dues paying families in 1910 to 190 in 1930. In 1928, the congregation added a community house, named after Henry Cohen, next to their synagogue which included new classrooms and an auditorium

B'nai Israel's current temple, constructed in 1955.

B'nai Israel's current temple, constructed in 1955.

Congregations in the Mid-20th Century

The economic hardships of the Great Depression affected each of the city’s congregations, but its most significant impact was on the Orthodox community. With both Orthodox congregations facing financial hardship in 1930, they finally agreed to set aside their differences and unite to form a new congregation, Beth Jacob, which was officially chartered in 1931. The new congregation hired Rabbi Louis Feigon, who helped negotiate the merger of the two factions. Max Baum, who had been president of the YMHA congregation became the first president of Beth Jacob. In 1932, the new congregation built a brick synagogue at 24th street and Avenue K. The old synagogue of the Hebrew Orthodox Benevolent Association was used as a Talmud Torah, holding both weekday Hebrew school and Sunday school for the children of the congregation. Rabbi Feigon led the Orthodox congregation for 29 years until his retirement in 1959. Beth Jacob remained Orthodox for several decades, holding daily minyans in both the morning and evening. George Berkman served the congregation as a shochet for over 25 years. In 1971, Beth Jacob decided to affiliate with the Conservative Movement and hired Jerome Epstein, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary, to be their rabbi.

The economic hardships of the Great Depression affected each of the city’s congregations, but its most significant impact was on the Orthodox community. With both Orthodox congregations facing financial hardship in 1930, they finally agreed to set aside their differences and unite to form a new congregation, Beth Jacob, which was officially chartered in 1931. The new congregation hired Rabbi Louis Feigon, who helped negotiate the merger of the two factions. Max Baum, who had been president of the YMHA congregation became the first president of Beth Jacob. In 1932, the new congregation built a brick synagogue at 24th street and Avenue K. The old synagogue of the Hebrew Orthodox Benevolent Association was used as a Talmud Torah, holding both weekday Hebrew school and Sunday school for the children of the congregation. Rabbi Feigon led the Orthodox congregation for 29 years until his retirement in 1959. Beth Jacob remained Orthodox for several decades, holding daily minyans in both the morning and evening. George Berkman served the congregation as a shochet for over 25 years. In 1971, Beth Jacob decided to affiliate with the Conservative Movement and hired Jerome Epstein, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary, to be their rabbi.

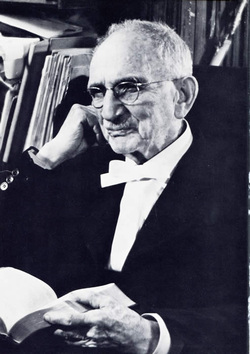

Rabbi Henry Cohen, late in his long career.

Rabbi Henry Cohen, late in his long career.

B’nai Israel continued to be influenced by Rabbi Henry Cohen, even after he passed away in 1952. His vision of social justice undoubtedly inspired the congregation’s leadership to open the “Temple Academy” in 1957. At a time when Galveston was still racially segregated and there was no public kindergarten for blacks, the temple’s preschool and kindergarten accepted students of all races. After the Selma march in 1965, B’nai Israel’s board voted to give money to Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. B’nai Israel reached its peak membership in 1945 with 239 families. After Rabbi Cohen retired in 1950, B’nai Israel had a series of rabbis over the next several decades. Rabbi Jimmy Kessler came to B’nai Israel in 1976, leaving after only five years. He returned to the congregation in 1989, and remained B’nai Israel’s rabbi until 2014. Kessler is also a trained historian and was the founder of the Texas Jewish Historical Society.

In 1953, B’nai Israel decided to move out of their grand synagogue and build a more modern, functional one. The new temple, completed in 1955, had air conditioning and only one story so elderly members did not have to climb a flight of stairs as they had to do in the old temple. This was a growing concern as the membership of B’nai Israel was graying, as many of the children raised in the congregation left Galveston for greater economic opportunities in larger cities. By 1976, B’nai Israel was down to 177 dues paying members; 20 years later, only 132 families belonged to the congregation. This corresponded with a decline in the city’s Jewish population, which went from 1200 people in 1948 to only 680 twenty years later. Despite this decline, the financial generosity of a few members, including the Kempner and Seinsheimer families, kept B’nai Israel afloat.

In 1953, B’nai Israel decided to move out of their grand synagogue and build a more modern, functional one. The new temple, completed in 1955, had air conditioning and only one story so elderly members did not have to climb a flight of stairs as they had to do in the old temple. This was a growing concern as the membership of B’nai Israel was graying, as many of the children raised in the congregation left Galveston for greater economic opportunities in larger cities. By 1976, B’nai Israel was down to 177 dues paying members; 20 years later, only 132 families belonged to the congregation. This corresponded with a decline in the city’s Jewish population, which went from 1200 people in 1948 to only 680 twenty years later. Despite this decline, the financial generosity of a few members, including the Kempner and Seinsheimer families, kept B’nai Israel afloat.

A.R. "Babe Schwartz

A.R. "Babe Schwartz

Civic Engagement

Despite this decline, Galveston Jews have continued to play a leading role in the civic affairs of the city, following a pattern set in the earliest days of Jewish settlement on the island. Morris Lasker represented Galveston in the state senate in the 1890s. Isidore Lovenberg spent 30 years on the Galveston School Board; a local junior high school was named in his honor. I.H. Kempner, one of the leading businessmen in the city, served as mayor from 1917 to 1919. Two decades later, Adrian Levy became mayor, leading the city from 1935 to 1939. During his tenure, Levy cracked down on gambling, getting slot machines removed from restaurants and other public establishments. Eddie Schreiber spent much of the 1960s as mayor of Galveston; initially selected by his fellow city council members for the position in 1961, Schreiber was elected directly by the voters in 1965, 1967, and 1969.

Ruth Levy Kempner became the first woman elected to the city council in 1961. Barbara Crews served as Galveston’s mayor from 1990 to 1996 after spending several years on the city council. A.R. “Babe” Schwartz represented Galveston in the Texas state legislature as a liberal Democrat from 1955 to 1981. Schwartz was a strong supporter of environmental laws and Civil Rights. Once, when the Ku Klux Klan sent each legislator an honorary membership card, Schwartz denounced the organization on the floor of the Texas House, declaring that one couldn’t be an honorable member of a dishonorable organization.While the phenomenon of Jewish mayors and officeholders has been rather common in the South, the number of Jews elected to political office in Galveston is quite remarkable and reflects a unique level of integration into the larger community.

Despite this decline, Galveston Jews have continued to play a leading role in the civic affairs of the city, following a pattern set in the earliest days of Jewish settlement on the island. Morris Lasker represented Galveston in the state senate in the 1890s. Isidore Lovenberg spent 30 years on the Galveston School Board; a local junior high school was named in his honor. I.H. Kempner, one of the leading businessmen in the city, served as mayor from 1917 to 1919. Two decades later, Adrian Levy became mayor, leading the city from 1935 to 1939. During his tenure, Levy cracked down on gambling, getting slot machines removed from restaurants and other public establishments. Eddie Schreiber spent much of the 1960s as mayor of Galveston; initially selected by his fellow city council members for the position in 1961, Schreiber was elected directly by the voters in 1965, 1967, and 1969.

Ruth Levy Kempner became the first woman elected to the city council in 1961. Barbara Crews served as Galveston’s mayor from 1990 to 1996 after spending several years on the city council. A.R. “Babe” Schwartz represented Galveston in the Texas state legislature as a liberal Democrat from 1955 to 1981. Schwartz was a strong supporter of environmental laws and Civil Rights. Once, when the Ku Klux Klan sent each legislator an honorary membership card, Schwartz denounced the organization on the floor of the Texas House, declaring that one couldn’t be an honorable member of a dishonorable organization.While the phenomenon of Jewish mayors and officeholders has been rather common in the South, the number of Jews elected to political office in Galveston is quite remarkable and reflects a unique level of integration into the larger community.

Col. Bubbie's remains in business today

Col. Bubbie's remains in business today

The Late 20th Century

Over the last decades of the 20th century, Galveston Jews largely moved out of the commercial sector of the economy, although a few remained. Most notably, Meyer Reiswerg opened the renowned “Col. Bubbie’s Strand Surplus Senter,” a purveyor of authentic military surplus merchandise, in 1972. Though Reiswerg died in 2009, his iconic store remains in business on Galveston’s downtown Strand. By the 1970s, Galveston Jews were more likely to work at the University of Texas Medical Branch on the island than to own a downtown store. According to Rabbi Kessler, about one-third of B’nai Israel’s members were affiliated with the medical school in 1976. Dr. William Cohn Levin served as president of the medical school from 1974 to 1987.

Over the last decades of the 20th century, Galveston Jews largely moved out of the commercial sector of the economy, although a few remained. Most notably, Meyer Reiswerg opened the renowned “Col. Bubbie’s Strand Surplus Senter,” a purveyor of authentic military surplus merchandise, in 1972. Though Reiswerg died in 2009, his iconic store remains in business on Galveston’s downtown Strand. By the 1970s, Galveston Jews were more likely to work at the University of Texas Medical Branch on the island than to own a downtown store. According to Rabbi Kessler, about one-third of B’nai Israel’s members were affiliated with the medical school in 1976. Dr. William Cohn Levin served as president of the medical school from 1974 to 1987.

The Jewish Community in Galveston Today

Today, the Jewish community of Galveston is shrinking. B’nai Israel has 130 member households, while Beth Jacob’s membership is less than half that. Currently, Beth Jacob brings in a visiting rabbi a few times a year to lead services. The congregation has not had its own religious school since the early 1990s. Hurricane Ike, which hit Galveston in 2008, had a big impact on the Jewish community with both synagogues sustaining storm damage. After Beth Jacob’s sanctuary and chapel were flooded during the storm, the congregation met for services in their front lobby. Rabbi Kessler led High Holiday services outside that year since B’nai Israel’s temple had no electricity. The homes of many members of both congregations were damaged. Perhaps most ominously for the Jewish community, the UT Medical Branch announced a significant downsizing in the wake of the storm. Galveston also has to deal with the ever encroaching borders of the Houston metropolitan area. Many Jews who work on the island choose to live in the southeastern suburbs of Houston. New Jewish congregations in places like Clear Lake have cut into the Galveston congregations.

Whatever the future holds for the Jewish community, its legacy as a central part of Galveston’s history and development is assured.

Whatever the future holds for the Jewish community, its legacy as a central part of Galveston’s history and development is assured.