Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Greenville, Texas

Greenville: Historical Overview

The first Texas state legislature founded Hunt County in 1846 in an effort to settle the fertile Blackland Prairies. Settlers built a log courthouse on the west side of the public square after the auction of land plots, and the city grew outward as agricultural development picked up in the area.

By the mid-1870s, cotton had become king in Greenville and Jewish merchants played an integral role in the cash crop economy that developed in the city. The Greenville Cotton Compress set records for the number of bales of cotton compressed for rail shipment to Galveston, and it was popularly believed that factories in Liverpool and Manchester preferred Greenville cotton. Jewish merchants observed the growing population of farmers in need of dry goods and other supplies, and set up businesses to meet the demands of Greenville residents.

In every stage of the city’s development- from log cabins to corn to cotton- Jewish residents helped make the city what it is today.

By the mid-1870s, cotton had become king in Greenville and Jewish merchants played an integral role in the cash crop economy that developed in the city. The Greenville Cotton Compress set records for the number of bales of cotton compressed for rail shipment to Galveston, and it was popularly believed that factories in Liverpool and Manchester preferred Greenville cotton. Jewish merchants observed the growing population of farmers in need of dry goods and other supplies, and set up businesses to meet the demands of Greenville residents.

In every stage of the city’s development- from log cabins to corn to cotton- Jewish residents helped make the city what it is today.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Greenville

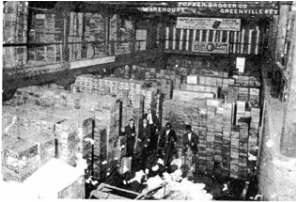

Edward Popper's wholesale grocery business

Edward Popper's wholesale grocery business

Early Settlers

After migrating from Austria-Hungary around 1880, Edward Popper moved to Greenville and opened a wholesale grocery store at the intersection of Lee and Wesley Streets. As one article in the local newspaper suggested, Popper’s business was “one of the best wholesale houses in north Texas” and brought many new business opportunities to the city. A local mule-driven transfer company sustained itself by moving goods for Popper’s business, and many residents found jobs at Popper’s business as clerks.

Jewish Businesses in Greenville

As the 19th century progressed, the cotton industry became increasingly mechanized. Accordingly, K.L. Lowenstein opened a machinery store on South Stonewall Street after he arrived in 1881. By 1890, Lowenstein was one of the most successful suppliers of agricultural machinery in north Texas. In the words of an 1895 edition of the Greenville Banner, Lowenstein’s name had become “a household word for cotton gins and mill equipment.” Below the article that praised Lowenstein, the newspaper predicted that “farm lands in Hunt County will double in price within the next five years,” a testament to the role Lowenstein played in making agriculture in Greenville a profitable endeavor. The success of the cotton industry in Greenville provided many families with disposable income, and Jewish merchants soon started selling more expensive and luxurious goods. Lazar Schwartz and his wife Sophia opened Schwartz’ Ladies Bazaar around 1895, providing clothing to “the ladies that worship the god of fashion.”

Even after the heyday of the cotton trade, Jewish merchants continued to open stores that deeply influenced the economy and the social climate of Greenville. Sam Glassman and his wife Anna left Russia in 1897 and made their way to Greenville in 1900. Sam Glassman most likely peddled goods for the first year he was in Greenville, finally earning enough money to open a dry goods store on the town square in 1901. Though he began his business career with a small inventory, Sam Glassman earned enough to extend his business interests into hides, furs, and scrap metal. Charles and Al Glassman took over the dry goods store in 1921, and during their tenure the business suffered what the local newspaper called “the most extensive and thorough burglary noted here in years.” The Glassmans lost $3,000 worth of dresses and men’s clothing, but the harm done by the thieves who broke into the store with hacksaws was nothing compared to the damage caused by the Great Depression. Sam Glassman had all of his savings in a local bank, and lost everything when the bank went under. Charles Glassman was able to keep the scrap metal business open and even expand into supplying rayon and oxygen, but the Glassmans closed down the dry goods store.

Greenville also provided Polish immigrant Sam Swartz with tremendous economic opportunity. In 1919, Swartz opened up a small retail business in a building, housing his family in the back of the small store. Swartz then bought a neighboring building, allowing him the space to expand his clothing inventory. By the time of Swartz’s retirement in 1973, the business had expanded to five times its original size. The local newspaper identified Swartz’s store as an example of the city’s development, suggesting that “the store has literally grown up with Greenville.” The store employed at least 25 clerks and department managers, and hired even more during busy retail seasons. Furthermore, Swartz managed his store in ways that resisted the strict racial order of the day. Unlike other shopkeepers in the town square, Swartz allowed black customers to enter the front door instead of the back.

Jewish merchants and the city of Greenville had a mutually beneficial relationship throughout the early 20th century, with Jewish merchants sustaining successful businesses that brought Greenville residents jobs. The success of merchants like Sam Glassman and Sam Swartz encouraged another wave of Jewish merchants to set up shop in Greenville during the 1920s and early 1930s. After migrating to the U.S. from Poland in 1873, William Rosenthal made his way to Greenville and opened a furniture store in the early 1920s. Census records show that William’s son Sam Rosenthal worked as a salesman for his father. When Prohibition legislation outlawed the sale of alcohol in 1920, German-born William Rosenberg left the wholesale liquor business and opened a seed shop to supply farmers in the Greenville area. Around 1930, Archie and Sol Skibell moved to Greenville, eventually opening the successful La Mode clothing store.

After migrating from Austria-Hungary around 1880, Edward Popper moved to Greenville and opened a wholesale grocery store at the intersection of Lee and Wesley Streets. As one article in the local newspaper suggested, Popper’s business was “one of the best wholesale houses in north Texas” and brought many new business opportunities to the city. A local mule-driven transfer company sustained itself by moving goods for Popper’s business, and many residents found jobs at Popper’s business as clerks.

Jewish Businesses in Greenville

As the 19th century progressed, the cotton industry became increasingly mechanized. Accordingly, K.L. Lowenstein opened a machinery store on South Stonewall Street after he arrived in 1881. By 1890, Lowenstein was one of the most successful suppliers of agricultural machinery in north Texas. In the words of an 1895 edition of the Greenville Banner, Lowenstein’s name had become “a household word for cotton gins and mill equipment.” Below the article that praised Lowenstein, the newspaper predicted that “farm lands in Hunt County will double in price within the next five years,” a testament to the role Lowenstein played in making agriculture in Greenville a profitable endeavor. The success of the cotton industry in Greenville provided many families with disposable income, and Jewish merchants soon started selling more expensive and luxurious goods. Lazar Schwartz and his wife Sophia opened Schwartz’ Ladies Bazaar around 1895, providing clothing to “the ladies that worship the god of fashion.”

Even after the heyday of the cotton trade, Jewish merchants continued to open stores that deeply influenced the economy and the social climate of Greenville. Sam Glassman and his wife Anna left Russia in 1897 and made their way to Greenville in 1900. Sam Glassman most likely peddled goods for the first year he was in Greenville, finally earning enough money to open a dry goods store on the town square in 1901. Though he began his business career with a small inventory, Sam Glassman earned enough to extend his business interests into hides, furs, and scrap metal. Charles and Al Glassman took over the dry goods store in 1921, and during their tenure the business suffered what the local newspaper called “the most extensive and thorough burglary noted here in years.” The Glassmans lost $3,000 worth of dresses and men’s clothing, but the harm done by the thieves who broke into the store with hacksaws was nothing compared to the damage caused by the Great Depression. Sam Glassman had all of his savings in a local bank, and lost everything when the bank went under. Charles Glassman was able to keep the scrap metal business open and even expand into supplying rayon and oxygen, but the Glassmans closed down the dry goods store.

Greenville also provided Polish immigrant Sam Swartz with tremendous economic opportunity. In 1919, Swartz opened up a small retail business in a building, housing his family in the back of the small store. Swartz then bought a neighboring building, allowing him the space to expand his clothing inventory. By the time of Swartz’s retirement in 1973, the business had expanded to five times its original size. The local newspaper identified Swartz’s store as an example of the city’s development, suggesting that “the store has literally grown up with Greenville.” The store employed at least 25 clerks and department managers, and hired even more during busy retail seasons. Furthermore, Swartz managed his store in ways that resisted the strict racial order of the day. Unlike other shopkeepers in the town square, Swartz allowed black customers to enter the front door instead of the back.

Jewish merchants and the city of Greenville had a mutually beneficial relationship throughout the early 20th century, with Jewish merchants sustaining successful businesses that brought Greenville residents jobs. The success of merchants like Sam Glassman and Sam Swartz encouraged another wave of Jewish merchants to set up shop in Greenville during the 1920s and early 1930s. After migrating to the U.S. from Poland in 1873, William Rosenthal made his way to Greenville and opened a furniture store in the early 1920s. Census records show that William’s son Sam Rosenthal worked as a salesman for his father. When Prohibition legislation outlawed the sale of alcohol in 1920, German-born William Rosenberg left the wholesale liquor business and opened a seed shop to supply farmers in the Greenville area. Around 1930, Archie and Sol Skibell moved to Greenville, eventually opening the successful La Mode clothing store.

Sam and Anna Glassman with their children,

Sam and Anna Glassman with their children, circa 1905

Organized Jewish Life in Greenville

The rise of a Jewish merchant class in Greenville paralleled the growth of Jewish religious life in the city. Early settlers like Lowenstein and Popper helped to establish the Shaare Israel Congregation in 1899, but the congregation was mostly concerned with securing a Jewish burial ground. Shaare Israel Cemetery was purchased in 1899, serving a growing Jewish population that reached 52 people by 1907. Despite this number, Shaare Israel was not holding regular services at the time. Due to deaths and families moving to other areas, the Jewish population of Greenville fell into decline in the early part of the 20th century.

By 1919, only 32 Jews lived in Greenville, a decline in population that made the construction of a building seem impractical. The congregation was only holding services for the High Holidays at the time. Even after the Jewish population of Greenville began to pick up in the 1920s with the arrival of new merchants, reaching 49 people in 1937, the congregation did not expand because of Greenville’s proximity to Dallas. Many Jewish families like the Glassmans and Skibells belonged to the Dallas Reform congregation Temple Emanu-El, while a few families in Greenville belonged to more traditional congregations in Dallas. With synagogues, full-time rabbis, and religious schools available about 50 miles away in Dallas, few congregants found it necessary or feasible to construct a building in Greenville. However, the lack of a building did not stop Greenville Jews from worshiping in Greenville if the occasion called for it. William Rosenberg was voted secretary of the Congregation around 1920, and he and his family held services for the High Holidays in their large Victorian home for those who could not make it to Dallas. On numerous occasions, Greenville Jews also held Passover Seders in the Washington Hotel. Nevertheless, the majority of Jews in Greenville went to Dallas for religious services.

The rise of a Jewish merchant class in Greenville paralleled the growth of Jewish religious life in the city. Early settlers like Lowenstein and Popper helped to establish the Shaare Israel Congregation in 1899, but the congregation was mostly concerned with securing a Jewish burial ground. Shaare Israel Cemetery was purchased in 1899, serving a growing Jewish population that reached 52 people by 1907. Despite this number, Shaare Israel was not holding regular services at the time. Due to deaths and families moving to other areas, the Jewish population of Greenville fell into decline in the early part of the 20th century.

By 1919, only 32 Jews lived in Greenville, a decline in population that made the construction of a building seem impractical. The congregation was only holding services for the High Holidays at the time. Even after the Jewish population of Greenville began to pick up in the 1920s with the arrival of new merchants, reaching 49 people in 1937, the congregation did not expand because of Greenville’s proximity to Dallas. Many Jewish families like the Glassmans and Skibells belonged to the Dallas Reform congregation Temple Emanu-El, while a few families in Greenville belonged to more traditional congregations in Dallas. With synagogues, full-time rabbis, and religious schools available about 50 miles away in Dallas, few congregants found it necessary or feasible to construct a building in Greenville. However, the lack of a building did not stop Greenville Jews from worshiping in Greenville if the occasion called for it. William Rosenberg was voted secretary of the Congregation around 1920, and he and his family held services for the High Holidays in their large Victorian home for those who could not make it to Dallas. On numerous occasions, Greenville Jews also held Passover Seders in the Washington Hotel. Nevertheless, the majority of Jews in Greenville went to Dallas for religious services.

Charles Glassman

Charles Glassman

The Community Grows

The arrival of numerous Jewish families to Greenville around 1940 provided the necessary numbers for the Jewish community to engage in more organized philanthropy. Women from various Jewish families like the Glassmans, Skibells, Swartzes, and Tannenbaums organized a Jewish Women’s Club dedicated to “the purpose of social service work.” The women worked on such projects as supplying poor children in local schools with shoes, a work of charity undoubtedly inspired by their connection to dry goods and clothing retail. Though Jews in Greenville never had a specific building for worship, Jewish beliefs about community service permeated into homes, hotels, and schools throughout the city.

Greenville Jews enjoyed a friendly and cooperative relationship with the majority Christian population of the city. In 1919, the pastor of one church asked William Rosenberg to speak at a dedication ceremony celebrating the purchase of a new pipe organ. The newspaper called Rosenberg’s speech a “token of friendship” between Christian and Jewish citizens, as Rosenberg extended his “sincerest and heartfelt greeting” to the church-goers on behalf of the Jewish citizens of the city. Rosenberg’s invitation to address the people at a Christian dedication ceremony reveals the respect and admiration the majority Christian population had for Greenville’s Jewish residents. Cooperation between the two religious groups in Greenville continued further into the 20th century. Sam Glassman, son of Charles Glassman, remembered one instance in the 1940s when the Baptist church in Greenville opened up their basement so that Jews could use the space to worship. Despite religious differences, Greenville Christians respected Jews and incorporated them into their religious and social lives.

The arrival of numerous Jewish families to Greenville around 1940 provided the necessary numbers for the Jewish community to engage in more organized philanthropy. Women from various Jewish families like the Glassmans, Skibells, Swartzes, and Tannenbaums organized a Jewish Women’s Club dedicated to “the purpose of social service work.” The women worked on such projects as supplying poor children in local schools with shoes, a work of charity undoubtedly inspired by their connection to dry goods and clothing retail. Though Jews in Greenville never had a specific building for worship, Jewish beliefs about community service permeated into homes, hotels, and schools throughout the city.

Greenville Jews enjoyed a friendly and cooperative relationship with the majority Christian population of the city. In 1919, the pastor of one church asked William Rosenberg to speak at a dedication ceremony celebrating the purchase of a new pipe organ. The newspaper called Rosenberg’s speech a “token of friendship” between Christian and Jewish citizens, as Rosenberg extended his “sincerest and heartfelt greeting” to the church-goers on behalf of the Jewish citizens of the city. Rosenberg’s invitation to address the people at a Christian dedication ceremony reveals the respect and admiration the majority Christian population had for Greenville’s Jewish residents. Cooperation between the two religious groups in Greenville continued further into the 20th century. Sam Glassman, son of Charles Glassman, remembered one instance in the 1940s when the Baptist church in Greenville opened up their basement so that Jews could use the space to worship. Despite religious differences, Greenville Christians respected Jews and incorporated them into their religious and social lives.

Sam Swartz opened his store in 1919

Sam Swartz opened his store in 1919

The Community Declines

During the 1950s, the Jewish population in Greenville fell into decline. Due to economic opportunities available in places like Dallas and Lubbock, the Skibel and Stern families moved out of the city in the 1950s. All of Charles Glassman’s children besides Joan moved out of Greenville around the same time in the pursuit of professional jobs elsewhere. Despite this exodus, the Jewish presence in Greenville continued to influence Greenville’s economy and community life. Charles Glassman received the Worthy Citizen Award in 1952, and served as the president of the Greenville Chamber of Commerce from 1951 to 1953. During his time as president of the Chamber of Commerce, Glassman was instrumental in convincing the aircraft manufacturing company TEMCO to set up its operation at the old Greenville airfield. TEMCO’s presence in Greenville revitalized the economy and provided many jobs to Greenville residents. The Swartz’s owned the most successful store in Greenville and kept it open until the 1970s, providing the community with nearly 50 years of quality goods and jobs. Levy’s Jewelry Store, which had been started by Ruth and Harry Levy, was sold to Al Lowenstein by the early 1950s. Lowenstein ran the business until it closed in 2005, making it the last Jewish-owned business in Greenville.

During the 1950s, the Jewish population in Greenville fell into decline. Due to economic opportunities available in places like Dallas and Lubbock, the Skibel and Stern families moved out of the city in the 1950s. All of Charles Glassman’s children besides Joan moved out of Greenville around the same time in the pursuit of professional jobs elsewhere. Despite this exodus, the Jewish presence in Greenville continued to influence Greenville’s economy and community life. Charles Glassman received the Worthy Citizen Award in 1952, and served as the president of the Greenville Chamber of Commerce from 1951 to 1953. During his time as president of the Chamber of Commerce, Glassman was instrumental in convincing the aircraft manufacturing company TEMCO to set up its operation at the old Greenville airfield. TEMCO’s presence in Greenville revitalized the economy and provided many jobs to Greenville residents. The Swartz’s owned the most successful store in Greenville and kept it open until the 1970s, providing the community with nearly 50 years of quality goods and jobs. Levy’s Jewelry Store, which had been started by Ruth and Harry Levy, was sold to Al Lowenstein by the early 1950s. Lowenstein ran the business until it closed in 2005, making it the last Jewish-owned business in Greenville.

The Jewish Community in Greenville Today

Time and the movement of people to urban centers have led to the dwindling of Greenville’s Jewish population. Julius Nussbaum and his wife Joan Glassman Nussbaum remained in Greenville to run the family industrial oxygen business, and remained in town even after retiring in 1999. As the last Jews of Greenville, they were both heavily involved in civic affairs, and active members of Temple Emanu-El in Dallas. Greenville’s days as a stand-alone Jewish community have passed, and like the Nussbaums were, any Jews moving to town will likely be part of Dallas’ large metropolitan Jewish community.