Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Hempstead, Texas

Hempstead: Historical Overview

The history of the Hempstead Jewish community centers around the Schwarz family. They were among the first and last Jews to live in this small town 50 miles west of Houston. Their short-lived congregation and synagogue was even named after the patriarch of the Schwarz family, who was the first ordained rabbi to settle in Texas. While Hempstead never attracted large numbers of Jews, it holds a unique place in Texas Jewish history.

Like so many other Texas towns, Hempstead was born from the railroad. When the Houston & Texas Central Railroad announced its route in 1856, investors bought up land around it and created Hempstead. In 1858, the first train rolled through the area and Hempstead was officially incorporated. While the Civil War stunted its early development, Hempstead began to grow after the war. Located amidst prime cotton growing land, the town emerged as a regional shipping and processing center for the crop. Despite its location on the railroad, Hempstead remained a small town, with a population of only 1800 people in 1904.

Like so many other Texas towns, Hempstead was born from the railroad. When the Houston & Texas Central Railroad announced its route in 1856, investors bought up land around it and created Hempstead. In 1858, the first train rolled through the area and Hempstead was officially incorporated. While the Civil War stunted its early development, Hempstead began to grow after the war. Located amidst prime cotton growing land, the town emerged as a regional shipping and processing center for the crop. Despite its location on the railroad, Hempstead remained a small town, with a population of only 1800 people in 1904.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Hempstead

The Schwarz Family

The seed for Hempstead’s Jewish community was planted when Gabriel and Jeanette Schwarz decided to seek their fortune in Hempstead right after the Civil War. Gabriel opened a store, and tried to convince his brother Sam to join him in Hempstead. Sam had settled in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1858, volunteering for the Confederacy once the war broke out. Wounded twice, Sam was looking for a fresh start after the war, and joined his brother in Hempstead in 1866. Sam opened a store of his own and began to write glowing letters back home to Posen describing life in this southeast Texas town. Inspired by their uncle’s descriptions, Sam’s nephews decided to join him. Benno Schwarz was the first, coming to Hempstead in 1870, when he was 17 years old. He lived with Sam and his family initially, working as a clerk in his uncle’s store. Soon, his brothers Alfred, Leo, and George followed. Together, they owned B. Schwarz & Brothers Dry Goods Store.

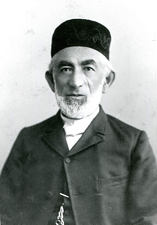

With four of his sons and two of his brothers living in Hempstead, Heinrich “Chayim” Schwarz made the fateful decision to leave Posen and immigrate with his wife and five other children. This was especially difficult since Chayim was an ordained rabbi and noted Hebrew scholar. At the time, the United States was known as a virtual wasteland for Jewish scholarship, let alone a small Texas town like Hempstead. Nevertheless, Schwarz and his wife decided that family was more important, and they came to Hempstead in 1873. Schwarz was the first rabbi in Texas to have official smicha (ordination), and brought over a Sefer Torah with him. While Rabbi Schwarz would occasionally lead services at Beth Israel in Houston and at Emanu-El in Dallas, he lived in Hempstead, continuing his scholarly work, including publishing poems and essays in Die Deborah, Isaac Mayer Wise’s Cincinnati-based German- language newspaper. Schwarz found a protégé and study partner in Jacob Voorsanger, spiritual leader of Houston’s Congregation Beth Israel. Voorsanger wrote a letter to the American Israelite newspaper calling Schwarz “one of the best Jewish scholars in the country” and suggesting that only his rudimentary knowledge of English prevented Schwarz from holding “the highest position in the land” as a rabbi and scholar.

The seed for Hempstead’s Jewish community was planted when Gabriel and Jeanette Schwarz decided to seek their fortune in Hempstead right after the Civil War. Gabriel opened a store, and tried to convince his brother Sam to join him in Hempstead. Sam had settled in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1858, volunteering for the Confederacy once the war broke out. Wounded twice, Sam was looking for a fresh start after the war, and joined his brother in Hempstead in 1866. Sam opened a store of his own and began to write glowing letters back home to Posen describing life in this southeast Texas town. Inspired by their uncle’s descriptions, Sam’s nephews decided to join him. Benno Schwarz was the first, coming to Hempstead in 1870, when he was 17 years old. He lived with Sam and his family initially, working as a clerk in his uncle’s store. Soon, his brothers Alfred, Leo, and George followed. Together, they owned B. Schwarz & Brothers Dry Goods Store.

With four of his sons and two of his brothers living in Hempstead, Heinrich “Chayim” Schwarz made the fateful decision to leave Posen and immigrate with his wife and five other children. This was especially difficult since Chayim was an ordained rabbi and noted Hebrew scholar. At the time, the United States was known as a virtual wasteland for Jewish scholarship, let alone a small Texas town like Hempstead. Nevertheless, Schwarz and his wife decided that family was more important, and they came to Hempstead in 1873. Schwarz was the first rabbi in Texas to have official smicha (ordination), and brought over a Sefer Torah with him. While Rabbi Schwarz would occasionally lead services at Beth Israel in Houston and at Emanu-El in Dallas, he lived in Hempstead, continuing his scholarly work, including publishing poems and essays in Die Deborah, Isaac Mayer Wise’s Cincinnati-based German- language newspaper. Schwarz found a protégé and study partner in Jacob Voorsanger, spiritual leader of Houston’s Congregation Beth Israel. Voorsanger wrote a letter to the American Israelite newspaper calling Schwarz “one of the best Jewish scholars in the country” and suggesting that only his rudimentary knowledge of English prevented Schwarz from holding “the highest position in the land” as a rabbi and scholar.

Chayim Schwarz. Photo courtesy of Texas Collection, Baylor University

Chayim Schwarz. Photo courtesy of Texas Collection, Baylor University

Organized Jewish Life in Hempstead

Chayim Schwarz was Orthodox, slaughtering his own kosher meat and fowl. His presence in Hempstead led the local Jewish community to begin to organize. During Passover, Schwarz would invite all of the town’s Jewish residents to his home for seder. As many as 60 people would gather around Chayim’s seder table. In 1880, Benno Schwarz, Chayim’s son, and his uncle Sam Schwarz built a small wooden synagogue behind Benno’s house. Although its official name was the Hempstead Hebrew Congregation, the synagogue was popularly known as Heychal Chayim, or Temple of Chayim. After Chayim Schwartz died in 1900, the congregation and its building became known as “Chayim Schwarz.” Chayim’s younger brother Sam took over the responsibility of leading services for the congregation.

Other Jewish Families in Hempstead

While the Schwarz family predominated, other Jewish immigrants also settled in Hempstead in the late 19th century. Prussian-born Joseph and Rachel Cohen lived in Louisiana and Arkansas before moving to Hempstead after the Civil War. By 1870, Joseph owned a dry goods and grocery store in town, while his oldest son Marks worked as a clerk there. Marks would go on to become a Waller County Commissioner in 1876. Marks Kempe left Germany in 1869, settling in Hempstead in the 1870s. Rather than opening a retail store like most other Hempstead Jews, Kempe bought land and became a farmer and rancher. When reporter and B’nai B’rith organizer Charles Wessolowsky visited Hempstead in 1879, he wrote that local Jews owned “large business houses” while others “engaged in agricultural pursuits.” Seeing Kempe’s farming operation inspired Wessolowsky to envision a series of Jewish farming colonies in Texas, although this idea never came to fruition. Childhood friends with the Schwarz family in Posen, the Galewsky brothers, Morris, Jake, and Haiman, followed them to Hempstead, opening a variety of businesses. Over the years, the Schwarz and Galewsky families became intermingled as their children married each other.

Chayim Schwarz was Orthodox, slaughtering his own kosher meat and fowl. His presence in Hempstead led the local Jewish community to begin to organize. During Passover, Schwarz would invite all of the town’s Jewish residents to his home for seder. As many as 60 people would gather around Chayim’s seder table. In 1880, Benno Schwarz, Chayim’s son, and his uncle Sam Schwarz built a small wooden synagogue behind Benno’s house. Although its official name was the Hempstead Hebrew Congregation, the synagogue was popularly known as Heychal Chayim, or Temple of Chayim. After Chayim Schwartz died in 1900, the congregation and its building became known as “Chayim Schwarz.” Chayim’s younger brother Sam took over the responsibility of leading services for the congregation.

Other Jewish Families in Hempstead

While the Schwarz family predominated, other Jewish immigrants also settled in Hempstead in the late 19th century. Prussian-born Joseph and Rachel Cohen lived in Louisiana and Arkansas before moving to Hempstead after the Civil War. By 1870, Joseph owned a dry goods and grocery store in town, while his oldest son Marks worked as a clerk there. Marks would go on to become a Waller County Commissioner in 1876. Marks Kempe left Germany in 1869, settling in Hempstead in the 1870s. Rather than opening a retail store like most other Hempstead Jews, Kempe bought land and became a farmer and rancher. When reporter and B’nai B’rith organizer Charles Wessolowsky visited Hempstead in 1879, he wrote that local Jews owned “large business houses” while others “engaged in agricultural pursuits.” Seeing Kempe’s farming operation inspired Wessolowsky to envision a series of Jewish farming colonies in Texas, although this idea never came to fruition. Childhood friends with the Schwarz family in Posen, the Galewsky brothers, Morris, Jake, and Haiman, followed them to Hempstead, opening a variety of businesses. Over the years, the Schwarz and Galewsky families became intermingled as their children married each other.

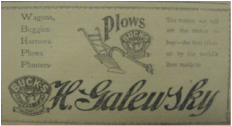

Ad for H. Galewsky

Ad for H. Galewsky

Jewish Businesses in Hempstead

By 1890, Jews owned an array of businesses in Hempstead. The various branches of the Schwarz family owned general stores, a lumber business, a marble works, a millinery business, and a grocery store. Arnold and William Joseph owned a dry goods store, while Herman Galewsky was a tinsmith, and later opened a hardware and farm implement store. Morris Galewsky owned a dry goods and clothing store. Women were often active in these businesses. Lena Schwarz owned a general store, while Minnie Schwarz had a hat business. Ida Schwarz worked in her husband Benno’s store. In 1907, the local newspaper reported that Ida had just come back from Dallas “with the newest and most up-to-date millinery in the city.” When Benno retired in 1914, his son H.D. took over the store, now called B. Schwarz and Son. Maurice Kempe, Marks’ son, opened a photography studio which remained in business until 1937.

Russian-born Isaac Aaron Stein came to America in 1903, settling in Hempstead. Starting as a peddler with a horse and wagon, Stein would travel the rural areas outside Hempstead selling goods to farmers. In 1904, he brought over his wife and children to join him and opened a small dry goods store. At first, Stein continued to peddle in the countryside while his wife Jane ran the store in Hempstead. Issac owned the business until he died in 1957; his son Mike and daughter-in-law Roselle then ran it until Mike’s death in 1970, after which it was sold.

By 1890, Jews owned an array of businesses in Hempstead. The various branches of the Schwarz family owned general stores, a lumber business, a marble works, a millinery business, and a grocery store. Arnold and William Joseph owned a dry goods store, while Herman Galewsky was a tinsmith, and later opened a hardware and farm implement store. Morris Galewsky owned a dry goods and clothing store. Women were often active in these businesses. Lena Schwarz owned a general store, while Minnie Schwarz had a hat business. Ida Schwarz worked in her husband Benno’s store. In 1907, the local newspaper reported that Ida had just come back from Dallas “with the newest and most up-to-date millinery in the city.” When Benno retired in 1914, his son H.D. took over the store, now called B. Schwarz and Son. Maurice Kempe, Marks’ son, opened a photography studio which remained in business until 1937.

Russian-born Isaac Aaron Stein came to America in 1903, settling in Hempstead. Starting as a peddler with a horse and wagon, Stein would travel the rural areas outside Hempstead selling goods to farmers. In 1904, he brought over his wife and children to join him and opened a small dry goods store. At first, Stein continued to peddle in the countryside while his wife Jane ran the store in Hempstead. Issac owned the business until he died in 1957; his son Mike and daughter-in-law Roselle then ran it until Mike’s death in 1970, after which it was sold.

Hempstead synagogue. Photo courtesy of the

Hempstead synagogue. Photo courtesy of the Gale Foundation.

The Congregation in the 20th Century

Congregation Chayim Schwarz continued to serve Hempstead’s small Jewish community even after Rabbi Schwarz died. By 1907, the congregation had 25 member families, holding services each Sabbath and on the High Holidays. While Sam Schwarz led these services in Hebrew, the congregation was beginning to move toward Reform Judaism; their Shabbat services were on Friday nights so their merchant members could open their stores on Saturday mornings. Rabbi Henry Barnstein of Houston’s Reform Congregation Beth Israel would travel to Hempstead as early as 1904 to perform weddings and funerals and occasionally address the congregation. In 1916, the congregation formally adopted the Reform Union Prayer Book, though it never joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

Hempstead Jews formed other groups that supported the work of the congregation. The congregation had a religious school with 20 children in 1907. The Jewish Ladies Aid Society ran the school and helped raise money to support the temple and the cemetery. In 1910, they organized a special children’s program for Purim. Hempstead Jewish women also had a purely social group, called The 42 Club, that held various social events in the early 20th century. Earlier, both men and women belonged to the Sam Schwarz Reading Circle, which had 27 members and met every Sunday in 1900.

Even after their leader Sam Schwarz died in 1918, the congregation Chayim Schwarz continued to hold regular services in their small, backyard shul for another two decades. Finally, by 1939, the congregation had dwindled in size to where they could no longer support regular services. Also, improved roads made travel to nearby Houston much easier, and Hempstead Jews began to join congregations in the state’s largest city. Their synagogue was rented out as housing, and was later torn down. The remaining members of the community decided to donate their Torah, the same scroll brought to Hempstead by Chayim Schwarz in 1873, to Houston’s newly founded Reform congregation Temple Emanu-El in 1944.

Congregation Chayim Schwarz continued to serve Hempstead’s small Jewish community even after Rabbi Schwarz died. By 1907, the congregation had 25 member families, holding services each Sabbath and on the High Holidays. While Sam Schwarz led these services in Hebrew, the congregation was beginning to move toward Reform Judaism; their Shabbat services were on Friday nights so their merchant members could open their stores on Saturday mornings. Rabbi Henry Barnstein of Houston’s Reform Congregation Beth Israel would travel to Hempstead as early as 1904 to perform weddings and funerals and occasionally address the congregation. In 1916, the congregation formally adopted the Reform Union Prayer Book, though it never joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

Hempstead Jews formed other groups that supported the work of the congregation. The congregation had a religious school with 20 children in 1907. The Jewish Ladies Aid Society ran the school and helped raise money to support the temple and the cemetery. In 1910, they organized a special children’s program for Purim. Hempstead Jewish women also had a purely social group, called The 42 Club, that held various social events in the early 20th century. Earlier, both men and women belonged to the Sam Schwarz Reading Circle, which had 27 members and met every Sunday in 1900.

Even after their leader Sam Schwarz died in 1918, the congregation Chayim Schwarz continued to hold regular services in their small, backyard shul for another two decades. Finally, by 1939, the congregation had dwindled in size to where they could no longer support regular services. Also, improved roads made travel to nearby Houston much easier, and Hempstead Jews began to join congregations in the state’s largest city. Their synagogue was rented out as housing, and was later torn down. The remaining members of the community decided to donate their Torah, the same scroll brought to Hempstead by Chayim Schwarz in 1873, to Houston’s newly founded Reform congregation Temple Emanu-El in 1944.

The Community Declines

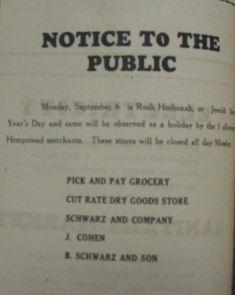

Although the congregation disbanded, Jewish merchants remained active in Hempstead. In 1937, five Jewish-owned businesses announced their closing for Rosh Hashanah in the local newspaper. In addition to B. Schwarz & Son and J. Cohen, these stores included Schwarz & Co., Cut Rate Dry Goods Store, and Pick and Pay Grocery, owned by Max Frenkil. His father G.K. Frenkil opened the business in 1913, and ran it for 23 years until his death in 1936. By the 1950s, there were only five Jewish families in Hempstead. They would travel to Houston for services and Sunday school. Although they were small in number, Hempstead Jews were economic and civic leaders in their community. Benno and Marks Schwarz were among the founding directors of Hempstead’s first local bank, the Citizens State Bank, established in 1906. Sam Schwarz spent 20 years on the local school board; in 1928, local officials named a black teacher training school after him. In 1913, several Hempstead Jewish merchants joined with other whites in donating money to help fund the local Juneteenth Celebration, marking the anniversary of when Texas slaves first learned of the Emancipation Proclamation. Mike Stein spent 14 years on the Hempstead school board, and eight on the city council in the 1960s. H.D. Schwarz served as a city commissioner from 1935 to 1940. His son, H.D. Schwarz Jr., served two long stints on the city council, from 1950 to 1966, and again in the 1970s.

Although the congregation disbanded, Jewish merchants remained active in Hempstead. In 1937, five Jewish-owned businesses announced their closing for Rosh Hashanah in the local newspaper. In addition to B. Schwarz & Son and J. Cohen, these stores included Schwarz & Co., Cut Rate Dry Goods Store, and Pick and Pay Grocery, owned by Max Frenkil. His father G.K. Frenkil opened the business in 1913, and ran it for 23 years until his death in 1936. By the 1950s, there were only five Jewish families in Hempstead. They would travel to Houston for services and Sunday school. Although they were small in number, Hempstead Jews were economic and civic leaders in their community. Benno and Marks Schwarz were among the founding directors of Hempstead’s first local bank, the Citizens State Bank, established in 1906. Sam Schwarz spent 20 years on the local school board; in 1928, local officials named a black teacher training school after him. In 1913, several Hempstead Jewish merchants joined with other whites in donating money to help fund the local Juneteenth Celebration, marking the anniversary of when Texas slaves first learned of the Emancipation Proclamation. Mike Stein spent 14 years on the Hempstead school board, and eight on the city council in the 1960s. H.D. Schwarz served as a city commissioner from 1935 to 1940. His son, H.D. Schwarz Jr., served two long stints on the city council, from 1950 to 1966, and again in the 1970s.

The Jewish Community in Hempstead Today

Today, only one Jewish family and business remain in Hempstead. Appropriately enough, it is the Schwarzes. H.D. “Trey” Schwarz III runs the department store that was started by his great grandfather Benno in 1871. Ironically, it was this very same store that once attracted the sons of Chayim Schwarz to Hempstead, and later the rabbi himself. Today, few Jews are drawn to Hempstead, although the creeping edge of Houston’s western suburbs continues to shorten the distance between the cities. If Hempstead’s Jewish population ever grows in the future, it will be due to its proximity to this metropolis.

Sources

Weiner, Hollace Ava. Jewish Stars in Texas (College Station: Texas A&M Press, 1999).