Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Houston, Texas

Houston: Historical Overview

|

Two ambitious brothers, Augustus and John Allen, envisioned building a vibrant city in the new Texas Republic. Their creation, which they named after the hero of the Texas War for Independence, Sam Houston, was soon declared the temporary capital of the fledgling nation.

As the seat of government for the Texas Republic, Houston grew from 12 residents at the start of 1837 to 1500 people just four months later. After the capital moved to Austin in 1839, Houston turned to the region’s leading cash crop, cotton, to fuel its economy. Plantation owners would ship their cotton along with corn and animal hides to Houston, which would then travel by steamboat down the Buffalo Bayou to Galveston, where they would be shipped to major ports in the eastern U.S. and Europe. The construction of railroads in the 1850s and 60s linked Houston to the nation’s growing transportation network, and enabled the city to become a major commercial center for the southeast. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Houston

Jacob DeCordova

Jacob DeCordova

Early Settlers

Jews were attracted to Houston early in the city’s history. According to Elaine Maas, “Jews were among the early pioneers of Houston and were intimately involved in its development.” Michael Seeligson owned a store in Houston by 1839, though he soon moved to Galveston, where he later became mayor. Jacob DeCordova was one of the most prominent citizens in the town. DeCordova helped to create the Houston Chamber of Commerce in 1840, and later opened a real estate business, buying and selling land around Texas. During the 1840s, DeCordova served as an alderman and represented Harris County in the legislature. DeCordova and his land business moved to the state capital of Austin in 1852, where he worked to attract settlers to Texas. Lewis Levy, who moved to Houston with his wife Mary in 1841, was also involved in the real estate business; in 1843 he bought a parcel of land from Sam Houston. According to historian Helena Schlam, 17 Jewish adults lived in Houston in 1850. Of the 11 adult males, all but DeCordova were merchants.

Jews continued to settle in Houston during the 1850s. By 1860, 108 Jews, including 68 adults, lived in the Bayou City. All but six of the adults were immigrants, most from the German states. They concentrated in retail trade, owning 15% of the city’s stores in 1860. Most achieved economic success rather quickly. According to a report in the national Jewish newspaper, the Occident, most of Houston’s Jews “are in a prosperous pecuniary condition.” Indeed, of the 26 Jewish household heads living in the city in 1860, 16 owned more than $1000 in real estate.

Several Houston Jews became leaders of the local business community. Morris Levy and Henry Fox were both involved in creating a group that sought to connect Houston to the Gulf of Mexico through a ship channel. The eventual success of this project would later transform Houston. Fox served on the first board of directors of the Houston Board of Trade and Cotton Exchange and became president of the Houston National Exchange Bank. John Reichman served as an alderman and was the city secretary and treasurer during the 1870s.

Jews were attracted to Houston early in the city’s history. According to Elaine Maas, “Jews were among the early pioneers of Houston and were intimately involved in its development.” Michael Seeligson owned a store in Houston by 1839, though he soon moved to Galveston, where he later became mayor. Jacob DeCordova was one of the most prominent citizens in the town. DeCordova helped to create the Houston Chamber of Commerce in 1840, and later opened a real estate business, buying and selling land around Texas. During the 1840s, DeCordova served as an alderman and represented Harris County in the legislature. DeCordova and his land business moved to the state capital of Austin in 1852, where he worked to attract settlers to Texas. Lewis Levy, who moved to Houston with his wife Mary in 1841, was also involved in the real estate business; in 1843 he bought a parcel of land from Sam Houston. According to historian Helena Schlam, 17 Jewish adults lived in Houston in 1850. Of the 11 adult males, all but DeCordova were merchants.

Jews continued to settle in Houston during the 1850s. By 1860, 108 Jews, including 68 adults, lived in the Bayou City. All but six of the adults were immigrants, most from the German states. They concentrated in retail trade, owning 15% of the city’s stores in 1860. Most achieved economic success rather quickly. According to a report in the national Jewish newspaper, the Occident, most of Houston’s Jews “are in a prosperous pecuniary condition.” Indeed, of the 26 Jewish household heads living in the city in 1860, 16 owned more than $1000 in real estate.

Several Houston Jews became leaders of the local business community. Morris Levy and Henry Fox were both involved in creating a group that sought to connect Houston to the Gulf of Mexico through a ship channel. The eventual success of this project would later transform Houston. Fox served on the first board of directors of the Houston Board of Trade and Cotton Exchange and became president of the Houston National Exchange Bank. John Reichman served as an alderman and was the city secretary and treasurer during the 1870s.

Beth Israel on Franklin Street.

Beth Israel on Franklin Street. Photo courtesy of Beth Israel.

Early Organized Jewish Life in Houston

Soon after Jews settled in Houston, they began to pray together. The first reported minyan in the city took place in 1837, but it wasn’t until 1854, when they bought land for a cemetery, that Houston Jews began to organize community institutions. That same year, Lewis Levy raised money to help the Jewish yellow fever victims of New Orleans. In 1855, Levy led the way in creating the Hebrew Benevolent Association, which aimed to oversee the cemetery and care for the Jewish needy in the city. The local newspaper praised the association’s founders as “among the most kind-hearted, humane, and high-minded businessmen of our city.” Indeed, the Hebrew Benevolent Association was greatly respected in Houston and was invited to take part in the city’s July 4th parade in 1856.

In 1859, 32 men founded Texas’ first Jewish congregation, Beth Israel. At least four of these founders lived in other parts of Texas, in places as far away as Jefferson and Paris. Of the 21 founders who were listed in the 1860 census, all but one were merchants. None were Texas natives and only one had been born in the United States. Of the 20 immigrants, 60% were from Prussia, 15% from Bavaria, 15% from Poland, and 10% from Austria. Most of the founding members were young; their average age was less than 28. By and large, the founders were well established economically. Several had amassed significant fortunes. J. Colman, a Polish-born merchant, owned $36,000 in real estate and $15,000 in personal property in 1860. M. Levy owned $25,000 in real estate. Of this group of 21 founders, six owned slaves, though most only owned one as a house servant. The men who created Beth Israel in 1859 were young immigrants who found economic success in their new home.

Despite their prominent economic role in the city, most of these Jews observed traditional Jewish practices. The Occident reported in 1860 that most Houston Jews “keep the Sabbath and Festivals strictly and do no business whatever on the sacred days.” M. Levy, the first president of Beth Israel, had moved to the city from Charleston, where he had led an Orthodox breakaway group from the Beth Elohim congregation after it adopted Reform Judaism. When Beth Israel bought a wooden building in 1860 for use as a synagogue, it had separate seating for men and women. Members were fined if they entered the synagogue with their heads uncovered. They hired Rev. Zachariah Emmich in 1860 to lead services and provide kosher meat to the congregation as shochet. Not every member of the young congregation observed traditional Judaism. In 1861, Beth Israel’s leadership tried to enforce Sabbath observance on its members with a new rule requiring that they keep their stores closed on Saturdays. Several members were suspended from the congregation for violating the rule. In 1864, the men of the congregation took over the religious school that had been founded a year earlier by the women of Beth Israel, claiming that the women had taught “an objectionable catechism.”

After the Civil War, Beth Israel, which had 56 members in 1866, began to move away from strict Orthodoxy toward Reform Judaism. In 1868, members voted overwhelmingly to adopt Issac Mayer Wise’s Reform prayer book Minhag America. Some members must have been disgruntled by the decision as later all of the new prayer books were stolen from the synagogue. The congregation also began to discuss adding an organ to worship services, a controversial issue since playing a musical instrument violates traditional Judaism’s rules about Sabbath observance. In 1869, they narrowly voted against it. Four years later, Beth Israel’s members voted in favor of the organ. In 1874, Beth Israel joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, marking the completion of its evolution toward Reform Judaism.

In 1870 Beth Israel built a brick synagogue on the corner of Crawford and Franklin streets. For the cornerstone laying ceremony, the congregation held a grand parade that included the mayor and aldermen, local police, volunteer fire companies, the Masonic and Odd Fellows lodges, and a brass band. According to the local newspaper, a thousand people took part in the celebration and “all classes of Houstonians have taken a warm interest in [the synagogue’s] inauguration.” Newspaper editor and B’nai B’rith organizer Charles Wessolowsky visited Houston in 1879 and noted that the city’s Jews “can boast of wealth, talent, prominence and are much respected by the Gentiles.” He also reported that Beth Israel enjoyed “a full attendance of Jew and Gentile to the Friday evening service.” Within its new building, Beth Israel endured continual fights over ritual questions since it was the only Jewish congregation in Houston. Wessolowsky noted that a Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society Charity Ball was not well attended, suggesting that their serving of ham alienated more traditional Jews.

Finally, in 1887, a group of traditional members left Beth Israel and began to meet together for Orthodox services. Joining them were a small but growing number of recent immigrants from Eastern Europe. Houston had two different Orthodox minyans at the time, one Galician and one Russian. In 1891, the two groups joined together to form a new congregation, Adath Yeshurun. P.S. Nussbaum, who had been a member of Beth Israel, was the new congregation’s first president. They met in private homes and rented rooms initially before buying a small house in 1894 to use as a synagogue.

Soon after Jews settled in Houston, they began to pray together. The first reported minyan in the city took place in 1837, but it wasn’t until 1854, when they bought land for a cemetery, that Houston Jews began to organize community institutions. That same year, Lewis Levy raised money to help the Jewish yellow fever victims of New Orleans. In 1855, Levy led the way in creating the Hebrew Benevolent Association, which aimed to oversee the cemetery and care for the Jewish needy in the city. The local newspaper praised the association’s founders as “among the most kind-hearted, humane, and high-minded businessmen of our city.” Indeed, the Hebrew Benevolent Association was greatly respected in Houston and was invited to take part in the city’s July 4th parade in 1856.

In 1859, 32 men founded Texas’ first Jewish congregation, Beth Israel. At least four of these founders lived in other parts of Texas, in places as far away as Jefferson and Paris. Of the 21 founders who were listed in the 1860 census, all but one were merchants. None were Texas natives and only one had been born in the United States. Of the 20 immigrants, 60% were from Prussia, 15% from Bavaria, 15% from Poland, and 10% from Austria. Most of the founding members were young; their average age was less than 28. By and large, the founders were well established economically. Several had amassed significant fortunes. J. Colman, a Polish-born merchant, owned $36,000 in real estate and $15,000 in personal property in 1860. M. Levy owned $25,000 in real estate. Of this group of 21 founders, six owned slaves, though most only owned one as a house servant. The men who created Beth Israel in 1859 were young immigrants who found economic success in their new home.

Despite their prominent economic role in the city, most of these Jews observed traditional Jewish practices. The Occident reported in 1860 that most Houston Jews “keep the Sabbath and Festivals strictly and do no business whatever on the sacred days.” M. Levy, the first president of Beth Israel, had moved to the city from Charleston, where he had led an Orthodox breakaway group from the Beth Elohim congregation after it adopted Reform Judaism. When Beth Israel bought a wooden building in 1860 for use as a synagogue, it had separate seating for men and women. Members were fined if they entered the synagogue with their heads uncovered. They hired Rev. Zachariah Emmich in 1860 to lead services and provide kosher meat to the congregation as shochet. Not every member of the young congregation observed traditional Judaism. In 1861, Beth Israel’s leadership tried to enforce Sabbath observance on its members with a new rule requiring that they keep their stores closed on Saturdays. Several members were suspended from the congregation for violating the rule. In 1864, the men of the congregation took over the religious school that had been founded a year earlier by the women of Beth Israel, claiming that the women had taught “an objectionable catechism.”

After the Civil War, Beth Israel, which had 56 members in 1866, began to move away from strict Orthodoxy toward Reform Judaism. In 1868, members voted overwhelmingly to adopt Issac Mayer Wise’s Reform prayer book Minhag America. Some members must have been disgruntled by the decision as later all of the new prayer books were stolen from the synagogue. The congregation also began to discuss adding an organ to worship services, a controversial issue since playing a musical instrument violates traditional Judaism’s rules about Sabbath observance. In 1869, they narrowly voted against it. Four years later, Beth Israel’s members voted in favor of the organ. In 1874, Beth Israel joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, marking the completion of its evolution toward Reform Judaism.

In 1870 Beth Israel built a brick synagogue on the corner of Crawford and Franklin streets. For the cornerstone laying ceremony, the congregation held a grand parade that included the mayor and aldermen, local police, volunteer fire companies, the Masonic and Odd Fellows lodges, and a brass band. According to the local newspaper, a thousand people took part in the celebration and “all classes of Houstonians have taken a warm interest in [the synagogue’s] inauguration.” Newspaper editor and B’nai B’rith organizer Charles Wessolowsky visited Houston in 1879 and noted that the city’s Jews “can boast of wealth, talent, prominence and are much respected by the Gentiles.” He also reported that Beth Israel enjoyed “a full attendance of Jew and Gentile to the Friday evening service.” Within its new building, Beth Israel endured continual fights over ritual questions since it was the only Jewish congregation in Houston. Wessolowsky noted that a Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society Charity Ball was not well attended, suggesting that their serving of ham alienated more traditional Jews.

Finally, in 1887, a group of traditional members left Beth Israel and began to meet together for Orthodox services. Joining them were a small but growing number of recent immigrants from Eastern Europe. Houston had two different Orthodox minyans at the time, one Galician and one Russian. In 1891, the two groups joined together to form a new congregation, Adath Yeshurun. P.S. Nussbaum, who had been a member of Beth Israel, was the new congregation’s first president. They met in private homes and rented rooms initially before buying a small house in 1894 to use as a synagogue.

P.S. Nussbaum, a former Beth Israel member

P.S. Nussbaum, a former Beth Israel member

was the first president of Adath Yeshurun

The Early 20th Century

As Houston entered the 20th century, it was a regional center for commerce and trade with 78,000 residents. Yet a few developments in the early 20th century would eventually transform Houston into one of the largest cities in the United States. In 1900, nearby Galveston was destroyed by a catastrophic hurricane. What had been Texas’s most important port was leveled. In 1914, the ship channel project, begun in the 1870s, was finally completed, linking Houston to the Gulf of Mexico. With Galveston still reeling, Houston emerged as the major port city in the region, and eventually became the second busiest port in the United States. With the discovery of oil at nearby Spindletop in 1901, Houston became a major center for the refining and shipping of oil. Oil and petroleum products were the main cargo shipped out of the Port of Houston. By 1916, Houston’s population had grown to 146,000. Its Jewish population grew as well, reaching an estimated 11,000 people by 1927.

Much of this growth in Houston’s Jewish population was due to increasing numbers of immigrants from the Russian empire. The Galveston Movement, which sought to redirect Jewish immigration away from New York towards the center of the country through the Texas port, brought hundreds of Jews to Houston between 1907 and 1914. Most of these immigrants were Orthodox Jews, who needed to be able to walk to synagogue on the Sabbath. Immigrants who settled in Houston’s 5th Ward lived too far away from Adath Yeshurun. As a result, 16 men formed Adath Israel congregation in 1905. Initially the new Orthodox congregation held services at the home of their president, H. Wertheimer. In 1910, Adath Israel dedicated its first synagogue with a ceremony in which the rabbis of both Beth Israel and Adath Yeshurun took part. By 1916, Adath Israel had 60 members. Rabbi Jacob Geller led the congregation from 1910 until his death in 1930

As Orthodox Jewish immigrants moved into the 6th Ward, they established their own congregation, Adath Emeth, founded in 1910. The group, led by chazzan and shochet Meyer Epstein, rented a small house in which to hold services. Most of Adath Emeth’s founding members were recent immigrants from Russia or Austria who were still getting established economically. Several of them worked as street peddlers, trying to save money to open a store of their own. In 1912, Houston mayor Horace Baldwin Rice invited the fledgling congregation to hold its High Holiday services in the city auditorium. Later, Adath Emeth held joint High Holiday services with Adath Yeshurun. By 1916, Adath Emeth had 75 members. In 1918, the congregation bought a small house on the corner of Houston and Washington Avenue. Three years later, they tore down the house and built a synagogue on the site. When it burned down in 1923, Adath Emeth quickly constructed a new building.

As Houston entered the 20th century, it was a regional center for commerce and trade with 78,000 residents. Yet a few developments in the early 20th century would eventually transform Houston into one of the largest cities in the United States. In 1900, nearby Galveston was destroyed by a catastrophic hurricane. What had been Texas’s most important port was leveled. In 1914, the ship channel project, begun in the 1870s, was finally completed, linking Houston to the Gulf of Mexico. With Galveston still reeling, Houston emerged as the major port city in the region, and eventually became the second busiest port in the United States. With the discovery of oil at nearby Spindletop in 1901, Houston became a major center for the refining and shipping of oil. Oil and petroleum products were the main cargo shipped out of the Port of Houston. By 1916, Houston’s population had grown to 146,000. Its Jewish population grew as well, reaching an estimated 11,000 people by 1927.

Much of this growth in Houston’s Jewish population was due to increasing numbers of immigrants from the Russian empire. The Galveston Movement, which sought to redirect Jewish immigration away from New York towards the center of the country through the Texas port, brought hundreds of Jews to Houston between 1907 and 1914. Most of these immigrants were Orthodox Jews, who needed to be able to walk to synagogue on the Sabbath. Immigrants who settled in Houston’s 5th Ward lived too far away from Adath Yeshurun. As a result, 16 men formed Adath Israel congregation in 1905. Initially the new Orthodox congregation held services at the home of their president, H. Wertheimer. In 1910, Adath Israel dedicated its first synagogue with a ceremony in which the rabbis of both Beth Israel and Adath Yeshurun took part. By 1916, Adath Israel had 60 members. Rabbi Jacob Geller led the congregation from 1910 until his death in 1930

As Orthodox Jewish immigrants moved into the 6th Ward, they established their own congregation, Adath Emeth, founded in 1910. The group, led by chazzan and shochet Meyer Epstein, rented a small house in which to hold services. Most of Adath Emeth’s founding members were recent immigrants from Russia or Austria who were still getting established economically. Several of them worked as street peddlers, trying to save money to open a store of their own. In 1912, Houston mayor Horace Baldwin Rice invited the fledgling congregation to hold its High Holiday services in the city auditorium. Later, Adath Emeth held joint High Holiday services with Adath Yeshurun. By 1916, Adath Emeth had 75 members. In 1918, the congregation bought a small house on the corner of Houston and Washington Avenue. Three years later, they tore down the house and built a synagogue on the site. When it burned down in 1923, Adath Emeth quickly constructed a new building.

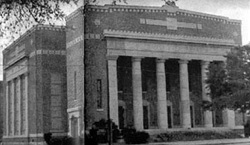

Beth Israel's Holman Street Temple.

Beth Israel's Holman Street Temple. Photo courtesy of Beth Israel.

As Houston’s newly arrived Jewish immigrants established their own religious groups, the city’s earliest and largest congregations continued to grow. Beth Israel numbered 87 members in 1900. Over the next quarter century, the congregation grew to 431 members. In 1908, Beth Israel dedicated a new $50,000 Romanesque synagogue on the corner of Crawford and Lamar Streets. The congregation soon outgrew its home, and built a new larger Greek-revival temple at Austin and Holman Streets in 1925. While Beth Israel had fourteen different rabbis between 1860 and 1900, the congregation established long-term stability in the position when it hired Rabbi Henry Barnstein. Arriving in 1900, the British-born rabbi brought a level of refinement and sophistication much appreciated by his congregants. Rabbi Barnstein was a lover of high culture, and helped to found the Houston Museum of Fine Arts and the Houston Symphony Society. Barnstein, who later changed his name to Barnston, served on the board of the Houston Public Library for 20 years. Beth Israel members were pleased that their rabbi became such a respected community leader and supported his interfaith work, which later benefited the congregation. When Beth Israel sold its temple in 1923, they met at the First Methodist Church for 18 months until their new synagogue was completed. In 1932, Beth Israel allowed the First Presbyterian Church to use its temple for an entire year after their church was damaged by a fire.

Adath Yeshurun's synagogue, built in 1908

Adath Yeshurun's synagogue, built in 1908

The Orthodox congregation Adath Yeshurun grew quickly in the new century, reaching 165 members by 1910. Adath Yeshurun hired its first rabbi, S. Glaser, in 1901, though the congregation had had several unordained chazzans previously. In 1905, Adath Yeshurun built a new synagogue, though they sold it two years later when the nearby Houston Belt and Terminal Company wanted it for their expansion. In 1908, Adath Yeshurun built a new home on the corner of Jackson Street and Walker Avenue. Reflecting the warm relationship between Houston’s two largest congregations, Rabbi Henry Barnstein of Beth Israel took part in the dedication ceremony. Interestingly, Adath Yeshurun’s rabbi, Wolf Willner, had briefly led Beth Israel in the 1890s. Prussian-born and Yale-educated, Rabbi Willner served Adath Yeshurun from 1907 to 1924. Rubin Kaplan was the congregation’s cantor from 1912 to 1932.

Willner’s tenure was not without conflict as the members squabbled over matters of ritual and finances. The dispute eventually boiled over when a disgruntled faction sued the congregation in 1911. Leaders of the Jewish community, including Rabbi Henry Cohen of Galveston, tried to mediate, but were unsuccessful. When the case finally went to trial in 1914, the judge worked out a compromise in which both factions would have equal representation on the board. This solution did not work, as a group tried to force out Rabbi Willner, barring him from entering Adath Yeshurun’s sanctuary. Willner led a group of his supporters down the street to the Knights of Columbus Hall, where they held services as Congregation Beth Shalom. This dispute did not last long; in 1916 the two congregations merged as Rabbi Willner became Adath Yeshurun’s rabbi once again. That year, Adath Yeshurun was the largest congregation in the city, with 260 members.

Willner’s tenure was not without conflict as the members squabbled over matters of ritual and finances. The dispute eventually boiled over when a disgruntled faction sued the congregation in 1911. Leaders of the Jewish community, including Rabbi Henry Cohen of Galveston, tried to mediate, but were unsuccessful. When the case finally went to trial in 1914, the judge worked out a compromise in which both factions would have equal representation on the board. This solution did not work, as a group tried to force out Rabbi Willner, barring him from entering Adath Yeshurun’s sanctuary. Willner led a group of his supporters down the street to the Knights of Columbus Hall, where they held services as Congregation Beth Shalom. This dispute did not last long; in 1916 the two congregations merged as Rabbi Willner became Adath Yeshurun’s rabbi once again. That year, Adath Yeshurun was the largest congregation in the city, with 260 members.

Members of the Jewish Literary Society in 1908

Members of the Jewish Literary Society in 1908

Jewish Organizations in Houston

While Houston Jews were divided into different congregations, a few organizations managed to unite them. Houston Jews established their first B’nai B’rith lodge in 1874. Additional B’nai B’rith chapters and lodges of other Jewish fraternal societies were founded later. Perhaps the most active, though short-lived, organization in the city was the Jewish Literary Society. From its founding in 1906, the society managed to bring together young adults from different segments of the Jewish community. It was originally designed to be a Zionist group, but attendees at its founding meeting decided to create a general Jewish organization that did not follow any particular ideology. Young people from all of the congregations, especially Beth Israel and Adath Yeshurun, joined the group, which numbered 400 members by 1915; both Rabbi Barnstein and Rabbi Willner served on its board.

The Jewish Literary Society was both a cultural and social organization, holding literary and musical programs twice a month as well as frequent social events. As the number of newly arrived immigrants in Houston grew, the society held a free night school to teach them English and American customs. In 1912, they even started their own Sunday school, enrolling 84 students on its opening day.

The Jewish Literary Society became an outspoken voice against anti-Semitic portrayals of Jews in local theaters. In 1909, they called for a boycott of local theaters that featured the so-called “stage Jew,” a stock character based on anti-Jewish stereotypes. Later, the group formed a committee to monitor theatrical productions and succeeded in eradicating “the stage Jew” from local theaters. Unfortunately, World War I seemed to sap the Jewish Literary Society of much of its energy, and the group disbanded in 1920.

Although the Jewish Literary Society sponsored a Yiddish night in 1912, Yiddish-speaking immigrants established their own Yiddish Library Society in 1916. A year later, the group had 100 members. Traveling Yiddish theater troupes stopped regularly in Houston. The Workmen’s Circle had a small but active chapter in Houston that worked to preserve Yiddish language and culture. Founded in 1915, the Workmen’s Circle had 30 members by 1916. In 1917, they brought famed Yiddish writer Scholem Asch to Houston, where he spoke to a packed house. Later, the Workmen’s Circle opened its own school to educate members’ children in Yiddish and Jewish culture and history.

Houston Jews created several organizations to care for those in need. In 1875, local women created the Jewish Women’s Benevolent Society. By 1909, it had 153 members and ran a lodging house for poor and transient Jews. In 1913, a group of Jewish women established a local chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women. The group soon opened a “working girls home” which offered a clean room and protective care to young single Jewish women in Houston, most of whom were recent immigrants. By 1916, the council had 177 members. In 1913, Houston Jews established a unified charity, bringing together the various Jewish charities in the city. In 1921, it became known as the Jewish Welfare Association. In 1945, the group changed its name to the Jewish Family Service and shifted its focus to helping families work through their problems with social workers and counselors. Ruth Fred served as director of the organization from 1940 to 1977. In 1936, community leaders created the Jewish Community Council to centralize and coordinate all the fundraising efforts of local Jewish organizations through one annual campaign. The Community Council, later known as the Jewish Federation, raised money for both local Jewish organizations and overseas causes. The Federation supported a range of social services, including the Seven Acres Home for the Jewish Aged, opened in 1977.

While Houston Jews were divided into different congregations, a few organizations managed to unite them. Houston Jews established their first B’nai B’rith lodge in 1874. Additional B’nai B’rith chapters and lodges of other Jewish fraternal societies were founded later. Perhaps the most active, though short-lived, organization in the city was the Jewish Literary Society. From its founding in 1906, the society managed to bring together young adults from different segments of the Jewish community. It was originally designed to be a Zionist group, but attendees at its founding meeting decided to create a general Jewish organization that did not follow any particular ideology. Young people from all of the congregations, especially Beth Israel and Adath Yeshurun, joined the group, which numbered 400 members by 1915; both Rabbi Barnstein and Rabbi Willner served on its board.

The Jewish Literary Society was both a cultural and social organization, holding literary and musical programs twice a month as well as frequent social events. As the number of newly arrived immigrants in Houston grew, the society held a free night school to teach them English and American customs. In 1912, they even started their own Sunday school, enrolling 84 students on its opening day.

The Jewish Literary Society became an outspoken voice against anti-Semitic portrayals of Jews in local theaters. In 1909, they called for a boycott of local theaters that featured the so-called “stage Jew,” a stock character based on anti-Jewish stereotypes. Later, the group formed a committee to monitor theatrical productions and succeeded in eradicating “the stage Jew” from local theaters. Unfortunately, World War I seemed to sap the Jewish Literary Society of much of its energy, and the group disbanded in 1920.

Although the Jewish Literary Society sponsored a Yiddish night in 1912, Yiddish-speaking immigrants established their own Yiddish Library Society in 1916. A year later, the group had 100 members. Traveling Yiddish theater troupes stopped regularly in Houston. The Workmen’s Circle had a small but active chapter in Houston that worked to preserve Yiddish language and culture. Founded in 1915, the Workmen’s Circle had 30 members by 1916. In 1917, they brought famed Yiddish writer Scholem Asch to Houston, where he spoke to a packed house. Later, the Workmen’s Circle opened its own school to educate members’ children in Yiddish and Jewish culture and history.

Houston Jews created several organizations to care for those in need. In 1875, local women created the Jewish Women’s Benevolent Society. By 1909, it had 153 members and ran a lodging house for poor and transient Jews. In 1913, a group of Jewish women established a local chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women. The group soon opened a “working girls home” which offered a clean room and protective care to young single Jewish women in Houston, most of whom were recent immigrants. By 1916, the council had 177 members. In 1913, Houston Jews established a unified charity, bringing together the various Jewish charities in the city. In 1921, it became known as the Jewish Welfare Association. In 1945, the group changed its name to the Jewish Family Service and shifted its focus to helping families work through their problems with social workers and counselors. Ruth Fred served as director of the organization from 1940 to 1977. In 1936, community leaders created the Jewish Community Council to centralize and coordinate all the fundraising efforts of local Jewish organizations through one annual campaign. The Community Council, later known as the Jewish Federation, raised money for both local Jewish organizations and overseas causes. The Federation supported a range of social services, including the Seven Acres Home for the Jewish Aged, opened in 1977.

Rabbi Wolf Willner

Rabbi Wolf Willner led both Beth Israel and

Adath Yeshurun during his career

Anti-Semitism in Houston

One problem the organized Jewish community had to face was anti-Semitism. In the early 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan rose to power and prominence in Houston and the rest of Texas. Journalist Billie Mayfield edited a weekly Klan newspaper in Houston that regularly used anti-Semitic stereotypes to attack Jews as parasites only interested in extracting wealth from the community. Mayfield wrote menacingly that “there are lots of good Jews in Houston and all over Texas; you find them with tombstones over their heads.” Despite this rhetoric, Jews were generally not targets of Klan violence, which usually focused on African Americans. During the Klan’s brief era of influence, some Jewish-owned stores downtown had their windows broken. The threat of the KKK, which helped elect Texas governors and U.S. senators during the 1920s, helped to unify the Houston Jewish community who spoke out against the racist, anti-immigrant organization. Rabbi Willner of Adath Yeshurun used his eulogy during the funeral of a local Jewish soldier who had died in World War I to denounce the Klan as cowardly, proclaiming that “the true American will not hide behind a mask of any kind.” In 1922, a grand jury, led by local Jewish businessman Sid Westheimer, issued a report denouncing the Klan. Houston Jews also boycotted businesses that advertised in the Klan newspaper. The Jewish Herald newspaper, started by Edgar Goldberg in 1908, also railed against the KKK. By 1924, the Klan had lost much of its local support and influence and Mayfield’s newspaper went out of business.

One problem the organized Jewish community had to face was anti-Semitism. In the early 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan rose to power and prominence in Houston and the rest of Texas. Journalist Billie Mayfield edited a weekly Klan newspaper in Houston that regularly used anti-Semitic stereotypes to attack Jews as parasites only interested in extracting wealth from the community. Mayfield wrote menacingly that “there are lots of good Jews in Houston and all over Texas; you find them with tombstones over their heads.” Despite this rhetoric, Jews were generally not targets of Klan violence, which usually focused on African Americans. During the Klan’s brief era of influence, some Jewish-owned stores downtown had their windows broken. The threat of the KKK, which helped elect Texas governors and U.S. senators during the 1920s, helped to unify the Houston Jewish community who spoke out against the racist, anti-immigrant organization. Rabbi Willner of Adath Yeshurun used his eulogy during the funeral of a local Jewish soldier who had died in World War I to denounce the Klan as cowardly, proclaiming that “the true American will not hide behind a mask of any kind.” In 1922, a grand jury, led by local Jewish businessman Sid Westheimer, issued a report denouncing the Klan. Houston Jews also boycotted businesses that advertised in the Klan newspaper. The Jewish Herald newspaper, started by Edgar Goldberg in 1908, also railed against the KKK. By 1924, the Klan had lost much of its local support and influence and Mayfield’s newspaper went out of business.

Simon Sakowitz

Simon Sakowitz

Jewish Businesses in the Early 20th Century

During the Klan’s brief reign in Texas, Houston Jews were not powerless. Indeed, from the time of their arrival in the 1840s, Houston Jews had played a visible and leading role in the local economy. By the 1920s, many of Houston’s big department stores, like Foley’s and Battlestein’s, were owned by Jews. Even newly arrived immigrants in the early 20th century became active parts of the local economy. In 1914, 50% of Adath Yeshurun’s members owned their own businesses, usually a grocery or dry goods store. Brothers Simon and Tobias Sakowitz left Russia as young children. In 1915, they opened a clothing store in Houston that eventually became Sakowitz’s, one of the finest department stores in the city. Tobias’ son Bernard later joined the business, which expanded to multiple locations in Houston as the city grew. In 1959, they built a new flagship store on Westheimer Road; ten years later the large Galleria mall was built across the street from it. Sakowitz’s overexpanded in the 1970s and declared bankruptcy during the economic downtown of the 1980s, selling most of the business to an Australian company. The Sakowitz stores closed for good in 1990.

Joe Weingarten was another Jewish immigrant who built a thriving business in Houston. Born in Poland, Weingarten came to America with his family while still a young boy. His father Harris Weingarten opened a grocery store in Houston in 1901. After he grew up, Joe joined the business, opening a second store in 1920. Joe Weingarten pioneered the innovations of cash and carry and self-service grocery stores in Houston, building a local chain that reached 70 locations by the time of his death in 1967. Weingarten was a prominent leader of the Houston Jewish community. After World War II, he signed one thousand blank affidavits for Jewish refugees guaranteeing that they would not become a public burden. Weingarten envisioned a world without violence, and founded the Institute for World Peace to help bring it about.

During the Klan’s brief reign in Texas, Houston Jews were not powerless. Indeed, from the time of their arrival in the 1840s, Houston Jews had played a visible and leading role in the local economy. By the 1920s, many of Houston’s big department stores, like Foley’s and Battlestein’s, were owned by Jews. Even newly arrived immigrants in the early 20th century became active parts of the local economy. In 1914, 50% of Adath Yeshurun’s members owned their own businesses, usually a grocery or dry goods store. Brothers Simon and Tobias Sakowitz left Russia as young children. In 1915, they opened a clothing store in Houston that eventually became Sakowitz’s, one of the finest department stores in the city. Tobias’ son Bernard later joined the business, which expanded to multiple locations in Houston as the city grew. In 1959, they built a new flagship store on Westheimer Road; ten years later the large Galleria mall was built across the street from it. Sakowitz’s overexpanded in the 1970s and declared bankruptcy during the economic downtown of the 1980s, selling most of the business to an Australian company. The Sakowitz stores closed for good in 1990.

Joe Weingarten was another Jewish immigrant who built a thriving business in Houston. Born in Poland, Weingarten came to America with his family while still a young boy. His father Harris Weingarten opened a grocery store in Houston in 1901. After he grew up, Joe joined the business, opening a second store in 1920. Joe Weingarten pioneered the innovations of cash and carry and self-service grocery stores in Houston, building a local chain that reached 70 locations by the time of his death in 1967. Weingarten was a prominent leader of the Houston Jewish community. After World War II, he signed one thousand blank affidavits for Jewish refugees guaranteeing that they would not become a public burden. Weingarten envisioned a world without violence, and founded the Institute for World Peace to help bring it about.

Civic Engagement

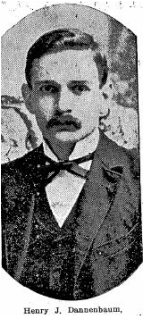

Weingarten was following a long tradition of Houston Jews being actively involved in the larger community. Henry Dannenbaum was a prominent Houston lawyer who served on the school board from 1904 to 1907. Dannenbaum became an outspoken critic of so-called “white slavery,” international prostitution rings that involved young immigrant women. Dannenbaum lobbied the government to pass the Mann Act, which made it illegal to transport women across state lines for immoral purposes. After the bill became law, Dannenbaum was asked to work as a special assistant in the Justice Department to enforce it. Dannenbaum returned to Houston after spending a year in Washington bringing prosecutions under the new law. In 1915, Governor James “Pa” Ferguson appointed Dannenbaum to a Harris County Judgeship. Dr. Ray Karchmer Daily, one of the first women to graduate from the University of Texas Medical School, became a nationally recognized ophthalmologist. In 1928, Dailey was elected to the Houston School Board on an anti-Klan platform. Dailey spent 24 years on the school board before her progressive politics and support of a federal school lunch program led to her defeat by an ardent anti-communist candidate during the height of the red scare.

Weingarten was following a long tradition of Houston Jews being actively involved in the larger community. Henry Dannenbaum was a prominent Houston lawyer who served on the school board from 1904 to 1907. Dannenbaum became an outspoken critic of so-called “white slavery,” international prostitution rings that involved young immigrant women. Dannenbaum lobbied the government to pass the Mann Act, which made it illegal to transport women across state lines for immoral purposes. After the bill became law, Dannenbaum was asked to work as a special assistant in the Justice Department to enforce it. Dannenbaum returned to Houston after spending a year in Washington bringing prosecutions under the new law. In 1915, Governor James “Pa” Ferguson appointed Dannenbaum to a Harris County Judgeship. Dr. Ray Karchmer Daily, one of the first women to graduate from the University of Texas Medical School, became a nationally recognized ophthalmologist. In 1928, Dailey was elected to the Houston School Board on an anti-Klan platform. Dailey spent 24 years on the school board before her progressive politics and support of a federal school lunch program led to her defeat by an ardent anti-communist candidate during the height of the red scare.

Jews were among the city’s leading philanthropists. Ben Taub, who was born and raised in Houston, became a successful real estate developer. Taub donated the land for the University of Houston when it was founded in 1936. Taub was very interested in medical care, and spent almost 30 years on the board of Jefferson Davis Hospital. He helped convince the Baylor College of Medicine to move to Houston in 1943, which led to the creation of a world-class medical center. Taub funded a new public charity hospital in 1964, which was named after him. The Jewish community followed Taub’s lead in supporting Houston’s health care facilities. In 1958, they decided to build a $450,000 Jewish Institute for Medical Research, which they donated to the Baylor College of Medicine when it was completed in 1964. Leopold Meyer was a major donor and fundraiser for the Texas Children’s Hospital. He was also the longtime director of two of Houston’s most iconic annual events: the Livestock Show and Rodeo, and the Pin Oak Horse Show.

Changes and Challenges

Zionism was at the heart of a bitter dispute that split Houston’s only Reform congregation. In the early 1940s, leaders of Beth Israel were concerned about the growing size of the congregation. Leaders were worried that these new members, many from Orthodox backgrounds, might push the classical Reform congregation in a more traditional direction. Zionism was especially controversial, as Beth Israel’s officers and board members saw Jews as a religious group not a separate people needing their own homeland. When Rabbi Barnston retired in 1943, the congregation hired Rabbi Hyman Judah Schachtel as their senior rabbi, passing over Associate Rabbi Robert Kahn who was serving overseas as a military chaplain. Schachtel was a member of the strongly anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism, while Kahn supported the Zionist cause. Upset over the opposition to Schachtel’s hiring by a minority of the members, the Beth Israel board created the “Basic Principles,” a statement of beliefs that each new member would have to ascribe to in order to receive voting rights within the congregation. Included in the principles, which were a restatement of the classical Reform tenets issued in the 1885 Pittsburgh Platform, was an opposition to a Jewish homeland.

Changes and Challenges

Zionism was at the heart of a bitter dispute that split Houston’s only Reform congregation. In the early 1940s, leaders of Beth Israel were concerned about the growing size of the congregation. Leaders were worried that these new members, many from Orthodox backgrounds, might push the classical Reform congregation in a more traditional direction. Zionism was especially controversial, as Beth Israel’s officers and board members saw Jews as a religious group not a separate people needing their own homeland. When Rabbi Barnston retired in 1943, the congregation hired Rabbi Hyman Judah Schachtel as their senior rabbi, passing over Associate Rabbi Robert Kahn who was serving overseas as a military chaplain. Schachtel was a member of the strongly anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism, while Kahn supported the Zionist cause. Upset over the opposition to Schachtel’s hiring by a minority of the members, the Beth Israel board created the “Basic Principles,” a statement of beliefs that each new member would have to ascribe to in order to receive voting rights within the congregation. Included in the principles, which were a restatement of the classical Reform tenets issued in the 1885 Pittsburgh Platform, was an opposition to a Jewish homeland.

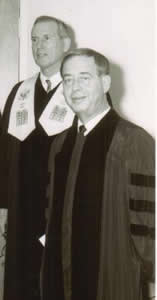

Rabbi Robert Kahn (left) and

Rabbi Robert Kahn (left) and Rabbi Hyman Schachtel.

Photo courtesy of Beth Israel.

At an extremely contentious congregational meeting, the members of Beth Israel voted to accept the “Basic Principles” as a requirement for full membership. In response, 142 people left Beth Israel, including Rabbi Kahn. In 1944, the breakaway group established their own Reform congregation, Emanu-El, and hired Robert Kahn to be their rabbi. After Israel was founded in 1948, Rabbi Schachtel renounced his membership in the Council of American Judaism and supported the Jewish state. The “Basic Principles” were revoked in the 1960s, though they had long since fallen into disuse, but the schism within Beth Israel created long-lasting bitterness within Houston’s Reform Jewish community.

The split of Beth Israel was not the first split within Houston’s Jewish congregations. In 1924, members of Adath Yeshurun who wanted to move away from strict Orthodoxy broke off to form Temple Beth El, a Conservative congregation. By 1926, Beth El had 210 members and was led by Rabbi Nathan Blechman. Beth El bought Beth Israel’s old temple in 1925, and remained there for the next 20 years. At Beth El, men and women sat together in the pews and sang together in the choir to an organ accompaniment. This split did not last however. In 1942, Beth El formed a joint religious school with Adath Yeshurun. Four years later, with the encouragement of Simon Greenberg, the provost at the Jewish Theological Seminary, the two congregations combined to form Beth Yeshurun. While the new congregation would be officially Conservative, Beth Yeshurun held daily Orthodox minyans in its chapel to accommodate traditional members, a practice which continues today. After the merger, Beth Yeshurun had almost one thousand members. Rabbi William Malev, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary, came to Beth Yeshurun in 1946, and led the congregation until 1973.

The split of Beth Israel was not the first split within Houston’s Jewish congregations. In 1924, members of Adath Yeshurun who wanted to move away from strict Orthodoxy broke off to form Temple Beth El, a Conservative congregation. By 1926, Beth El had 210 members and was led by Rabbi Nathan Blechman. Beth El bought Beth Israel’s old temple in 1925, and remained there for the next 20 years. At Beth El, men and women sat together in the pews and sang together in the choir to an organ accompaniment. This split did not last however. In 1942, Beth El formed a joint religious school with Adath Yeshurun. Four years later, with the encouragement of Simon Greenberg, the provost at the Jewish Theological Seminary, the two congregations combined to form Beth Yeshurun. While the new congregation would be officially Conservative, Beth Yeshurun held daily Orthodox minyans in its chapel to accommodate traditional members, a practice which continues today. After the merger, Beth Yeshurun had almost one thousand members. Rabbi William Malev, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary, came to Beth Yeshurun in 1946, and led the congregation until 1973.

Adath Emeth's Cleburne St. synagogue

Adath Emeth's Cleburne St. synagogue

Geographical Shifts

While Houston Jews initially lived in the wards adjacent to downtown, in the 1920s and 1930s they moved south to the Washington and Riverside Terrace neighborhoods, which became the center of the Houston Jewish community. Most of the city’s Jewish congregations and institutions moved to the neighborhood as well. The Orthodox synagogues, which needed to be close to their membership since they walked to synagogue on the Sabbath, were the first to move. In 1939, Adath Israel built a new synagogue in the Washington Terrace neighborhood. In 1937, a new Orthodox congregation, Beth Jacob, bought land at Cleburne and Hamilton upon which it built a small synagogue two years later. In 1948, Adath Emeth built a new synagogue at Cleburne and Ennis Streets. After the merger, Beth Yeshurun built a new synagogue in the neighborhood in 1950. Initially, the building, which consisted primarily of classrooms and administrative offices, did not have a sanctuary as the congregation met in the building’s auditorium for services. The Jewish Community Center, which had been founded in 1933, used a two-story building owned by the Jewish Community Council until it moved into a new facility on Herrman Drive in 1951.

Both the Jewish Community Center and Beth Yeshurun moved to Washington Terrace relatively late, and soon found that most of their members were relocating to new neighborhoods along South and North Braeswood Drives. As African Americans moved into Washington and Riverside Terrace, many white residents, including Jews, moved out. Jews, who were still excluded from such elite neighborhoods as River Oaks, moved to the new Meyerland area in the 1950s and 1960s. Once again, the city’s Jewish institutions relocated to be close to their membership. Beth Yeshurun decided not to build a sanctuary in their building, but rather to construct an entirely new building on Beechnut Street in Meyerland, which was completed in 1962. Adath Emeth sold their building to Texas Southern University, a state college for African Americans, in 1959 and built a new synagogue on North Braeswood Boulevard in 1960. Beth Jacob moved to the new Jewish neighborhood that same year. Beth Israel moved to a large new temple on North Braeswood in 1967. Two years later, the Jewish Community Center relocated to a new facility just across the Braes Bayou from Beth Israel on South Braeswood. By the 1970s, a majority of Houston’s Jews lived in the southwest part of the city in the Meyerland, Bellaire, and Braeswood neighborhoods. Children whose parents had gone to San Jacinto High School in Washington Terrace now went to Bellaire High School.

While Houston Jews initially lived in the wards adjacent to downtown, in the 1920s and 1930s they moved south to the Washington and Riverside Terrace neighborhoods, which became the center of the Houston Jewish community. Most of the city’s Jewish congregations and institutions moved to the neighborhood as well. The Orthodox synagogues, which needed to be close to their membership since they walked to synagogue on the Sabbath, were the first to move. In 1939, Adath Israel built a new synagogue in the Washington Terrace neighborhood. In 1937, a new Orthodox congregation, Beth Jacob, bought land at Cleburne and Hamilton upon which it built a small synagogue two years later. In 1948, Adath Emeth built a new synagogue at Cleburne and Ennis Streets. After the merger, Beth Yeshurun built a new synagogue in the neighborhood in 1950. Initially, the building, which consisted primarily of classrooms and administrative offices, did not have a sanctuary as the congregation met in the building’s auditorium for services. The Jewish Community Center, which had been founded in 1933, used a two-story building owned by the Jewish Community Council until it moved into a new facility on Herrman Drive in 1951.

Both the Jewish Community Center and Beth Yeshurun moved to Washington Terrace relatively late, and soon found that most of their members were relocating to new neighborhoods along South and North Braeswood Drives. As African Americans moved into Washington and Riverside Terrace, many white residents, including Jews, moved out. Jews, who were still excluded from such elite neighborhoods as River Oaks, moved to the new Meyerland area in the 1950s and 1960s. Once again, the city’s Jewish institutions relocated to be close to their membership. Beth Yeshurun decided not to build a sanctuary in their building, but rather to construct an entirely new building on Beechnut Street in Meyerland, which was completed in 1962. Adath Emeth sold their building to Texas Southern University, a state college for African Americans, in 1959 and built a new synagogue on North Braeswood Boulevard in 1960. Beth Jacob moved to the new Jewish neighborhood that same year. Beth Israel moved to a large new temple on North Braeswood in 1967. Two years later, the Jewish Community Center relocated to a new facility just across the Braes Bayou from Beth Israel on South Braeswood. By the 1970s, a majority of Houston’s Jews lived in the southwest part of the city in the Meyerland, Bellaire, and Braeswood neighborhoods. Children whose parents had gone to San Jacinto High School in Washington Terrace now went to Bellaire High School.

The Community Grows

As Jews moved to the southwest part of town, Houston was experiencing another economic boom that would once again transform the Jewish community. The development of the petrochemical industry along with the arrival of the National Aeronautical and Space Administration helped make Houston a world center of the energy and technology industries. The creation of the Houston Medical Center put the city on the forefront of health care and medical research; by 1990, the Medical Center was the city’s largest employer. The invention and wide use of air conditioning helped to make Houston’s brutal summers and humidity bearable. The city’s population grew from 384,000 people in 1940 to 1.2 million in 1970. By the 1970s, Houston was a thriving sunbelt city attracting people from other parts of the country where industry was in decline. The Jewish population grew as well, increasing from 13,500 Jews in 1937 to 42,500 by 1986. Jews raised in the Northeast and Midwest began to move to Houston in droves. According to a Jewish Federation study, only 20% of adult Houston Jews in 1986 had been born in the city. Over a quarter of Houston Jews had moved to the city in the previous six years.

Although the Houston Jewish community experienced tremendous growth in the 1970s and 1980s, it continued to be concentrated in the southwest part of the city. In fact, in 1986, 25% of the city’s Jewish population lived in only two zip codes, an amazing statistic considering Houston’s sprawling size. About half of Houston Jews lived in the Meyerland, Braeswood, and Bellaire areas. There was a plurality of Houston Jews: 47%, were Reform, while 29% were Conservative, and less than 5% were Orthodox. Only 8% of Houston Jews bought kosher food in 1986.

As Jews moved to the southwest part of town, Houston was experiencing another economic boom that would once again transform the Jewish community. The development of the petrochemical industry along with the arrival of the National Aeronautical and Space Administration helped make Houston a world center of the energy and technology industries. The creation of the Houston Medical Center put the city on the forefront of health care and medical research; by 1990, the Medical Center was the city’s largest employer. The invention and wide use of air conditioning helped to make Houston’s brutal summers and humidity bearable. The city’s population grew from 384,000 people in 1940 to 1.2 million in 1970. By the 1970s, Houston was a thriving sunbelt city attracting people from other parts of the country where industry was in decline. The Jewish population grew as well, increasing from 13,500 Jews in 1937 to 42,500 by 1986. Jews raised in the Northeast and Midwest began to move to Houston in droves. According to a Jewish Federation study, only 20% of adult Houston Jews in 1986 had been born in the city. Over a quarter of Houston Jews had moved to the city in the previous six years.

Although the Houston Jewish community experienced tremendous growth in the 1970s and 1980s, it continued to be concentrated in the southwest part of the city. In fact, in 1986, 25% of the city’s Jewish population lived in only two zip codes, an amazing statistic considering Houston’s sprawling size. About half of Houston Jews lived in the Meyerland, Braeswood, and Bellaire areas. There was a plurality of Houston Jews: 47%, were Reform, while 29% were Conservative, and less than 5% were Orthodox. Only 8% of Houston Jews bought kosher food in 1986.

Brith Shalom.

Brith Shalom. Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler.

This shrinking of the Orthodox population compelled the city’s three Orthodox congregations to merge in the mid-1960s. By the early 1960s, Beth Jacob had only 93 members while Adath Emeth was in financial trouble. In 1965, the two Orthodox congregations, which each had their own building, merged. The following year, Adath Israel joined as well, creating the United Orthodox Synagogues [UOS]. For a while after the merger, each congregation maintained their own distinct identity. Adath Emeth celebrated its own anniversary and issued a history of the congregation a few years after the merger. Although UOS primarily used Adath Emeth’s building, it also maintained Beth Jacob’s synagogue for several years. In 1966, UOS’s Rabbi Raphael Schwartzman, who had earlier served Adath Emeth, led services at the nearby Beth Jacob building once a month. A chapel at the UOS synagogue was named after Adath Israel. Despite its name, UOS was not strictly Orthodox in the 1960s. Men and women sat together and the synagogue’s mikvah (ritual bath) was rarely used. Members even drove to synagogue on the Sabbath, prompting the UOS board to close off the front driveway with a cement block on Saturday mornings so members could not park their cars in the building’s lot.

By 1971, UOS had 241 families. The congregation benefited when a large group of South African Jews moved to Houston in the late 1960s and 1970s and joined the city’s only Orthodox congregation. In 1976, Rabbi Joseph Radinsky came to UOS, leading the congregation for the next 27 years. Under Radinsky’s leadership, UOS gradually adopted more Orthodox practices, including separate seating for men and women. In 1996, the congregation set up an eruv in the area around the shul so members could carry things and push baby strollers as they walked to services on Shabbat. By 2006, UOS, now led by Rabbi Barry Gelman, had 374 member families.

As Houston’s Jewish community grew in the postwar years, they established new congregations. In the 1950s, two groups broke away from a couple of Houston’s large congregations. In 1955, a group who thought Beth Yeshurun had grown too large, left and formed Brith Shalom, a Conservative congregation that capped its membership at 300 families. Since then, the cap has been increased to 500 families. In 1957, a small faction unhappy with Beth Israel’s drift away from classical Reform left and created the Houston Congregation for Reform Judaism. The new congregation built a small temple in 1962. By 1971, the Houston Congregation for Reform Judaism had 100 members.

By 1971, UOS had 241 families. The congregation benefited when a large group of South African Jews moved to Houston in the late 1960s and 1970s and joined the city’s only Orthodox congregation. In 1976, Rabbi Joseph Radinsky came to UOS, leading the congregation for the next 27 years. Under Radinsky’s leadership, UOS gradually adopted more Orthodox practices, including separate seating for men and women. In 1996, the congregation set up an eruv in the area around the shul so members could carry things and push baby strollers as they walked to services on Shabbat. By 2006, UOS, now led by Rabbi Barry Gelman, had 374 member families.

As Houston’s Jewish community grew in the postwar years, they established new congregations. In the 1950s, two groups broke away from a couple of Houston’s large congregations. In 1955, a group who thought Beth Yeshurun had grown too large, left and formed Brith Shalom, a Conservative congregation that capped its membership at 300 families. Since then, the cap has been increased to 500 families. In 1957, a small faction unhappy with Beth Israel’s drift away from classical Reform left and created the Houston Congregation for Reform Judaism. The new congregation built a small temple in 1962. By 1971, the Houston Congregation for Reform Judaism had 100 members.

Temple Emanu-El.

Temple Emanu-El. Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Temple Emanu-El grew quickly after its founding in 1944. Within 25 years it had grown larger than Beth Israel, numbering 1,390 member families by 1971. For the congregation’s first five years, they met at Central Presbyterian Church and held their religious school at a local public elementary school. In 1949, Emanu-El dedicated its first and only synagogue across from Rice University. Texas Governor Allan Shivers spoke at the dedication. Described as having “revolutionary architecture” by a local newspaper, the temple was extremely modern for its time, and for several years architectural sightseers would visit Emanu-El. Rabbi Robert Kahn led Emanu-El from 1945 until he retired in 1978. Rabbi Kahn was an outspoken voice for social justice and civil rights in Houston, working behind-the-scenes to convince Foley’s, a large Jewish-owned department store in Houston, to integrate peacefully. In 1965, at the urging of Rabbi Kahn, Emanu-El’s board passed a resolution calling for its members not to discriminate and promising not to do business with organizations that discriminated on the basis of race. After Rabbi Kahn’s retirement, Roy Walter, who had been an assistant rabbi at Emanu-El since 1970, became senior rabbi. Walter ended his 41-year tenure at Emanu-El when he retired in 2011.

Despite the growth in the number of synagogues, Houston’s Jewish community is still concentrated in the city’s three largest congregations. According to a 2001 study, 60% of the city’s affiliated Jews belonged to either Beth Yeshurun, Emanu-El, or Beth Israel. In 1971, Beth Yeshurun had 1750 members and a flourishing Jewish elementary day school. Rabbi Jack Segal succeeded Rabbi Malev as senior rabbi in 1973, serving for 23 years. Beth Yeshurun had 2170 families in 2011, making it the largest Conservative congregation in the United States. Despite its roots as an Orthodox congregation, Beth Yeshurun gave its female members equal rights relatively early. In 1975, the Conservative congregation decided to count women towards a minyan and allowed them to receive Torah honors and read Torah from the bimah. In 1980, Helen Schaffer became the first woman elected president of Beth Yeshurun. By 1971, Beth Israel had 1235 members. When Rabbi Schachtel retired in 1975, he was followed by Rabbi Samuel Karff, who led Beth Israel for the next 24 years. Beth Israel had 1700 member families in 2011.

Despite the growth in the number of synagogues, Houston’s Jewish community is still concentrated in the city’s three largest congregations. According to a 2001 study, 60% of the city’s affiliated Jews belonged to either Beth Yeshurun, Emanu-El, or Beth Israel. In 1971, Beth Yeshurun had 1750 members and a flourishing Jewish elementary day school. Rabbi Jack Segal succeeded Rabbi Malev as senior rabbi in 1973, serving for 23 years. Beth Yeshurun had 2170 families in 2011, making it the largest Conservative congregation in the United States. Despite its roots as an Orthodox congregation, Beth Yeshurun gave its female members equal rights relatively early. In 1975, the Conservative congregation decided to count women towards a minyan and allowed them to receive Torah honors and read Torah from the bimah. In 1980, Helen Schaffer became the first woman elected president of Beth Yeshurun. By 1971, Beth Israel had 1235 members. When Rabbi Schachtel retired in 1975, he was followed by Rabbi Samuel Karff, who led Beth Israel for the next 24 years. Beth Israel had 1700 member families in 2011.

The Jewish Community in Houston Today

Ellen Cohen

Ellen Cohen

By the 21st century, the Houston Jewish community was closely integrated into the economic, social, and political life of the city. Jews have been very involved in civic affairs, serving on boards of local hospitals and charities. No longer concentrated in the retail business, Jews have moved into the professions and corporate positions. They have been elected to political office with little issue being made about their Jewishness. Debra Danburg represented Houston in the state legislature from 1980 to 2002. Ellen Cohen represented the city in the legislature from 2007 to 2010. Norman Black, a local attorney, was appointed to the Federal bench by President Carter in 1979. Ruby Sondock became the first woman to serve on the Texas Supreme Court when Governor Bill Clements appointed her to the position in 1982.

While Jews remain concentrated in the southwest part of Houston, they began to move to other areas of the sprawling city in the 1980s and 1990s, establishing congregations in far-flung areas like Spring, Humble, and the Woodlands. By 2011, the Houston area was home to 23 different congregations; 40 years earlier, Houston had only six Jewish congregations. An estimated 45,000 Jews live in the Houston area, though there has not been a scientific population study of the community in several years. Over the last few decades, the city’s Jewish population has not grown as fast as that of other southern cities like Atlanta, Austin, or Charlotte, yet Houston remains a vibrant, flourishing community with a strong economy and a wide array of Jewish resources.

While Jews remain concentrated in the southwest part of Houston, they began to move to other areas of the sprawling city in the 1980s and 1990s, establishing congregations in far-flung areas like Spring, Humble, and the Woodlands. By 2011, the Houston area was home to 23 different congregations; 40 years earlier, Houston had only six Jewish congregations. An estimated 45,000 Jews live in the Houston area, though there has not been a scientific population study of the community in several years. Over the last few decades, the city’s Jewish population has not grown as fast as that of other southern cities like Atlanta, Austin, or Charlotte, yet Houston remains a vibrant, flourishing community with a strong economy and a wide array of Jewish resources.

Sources

Maas, Elaine. The Jews of Houston: An Ethnographic Study (New York: AMS Press, 1989).