Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Jefferson, Texas

Jefferson: Historical Overview

In 1845, an advertisement in a local newsletter urged immigrants to make their way to Jefferson: “Merchants and planters will find it to their advantage to ship their goods and cotton at Jefferson as its steamboat navigation is considered by all to be excellent and safe.” Soon after, drawn by these amenities, many immigrants started arriving in Jefferson, including Jews.

Incorporated in 1848, the town was perfectly located at the intersection of a steamboat port and early wagon routes. By 1850, the population had boomed to just over 2,000, of which, according to one estimate, 8% were Jews. Jefferson became a thriving commercial center, in which Jews played a crucial role, until 1873, when various factors led to its decline. The earliest Jewish settlers in Jefferson were German immigrants who clustered in homes along Houston Street in the southwestern part of the city. Thereafter, residents referred to the area as “Jew Town” or the “Jewish Section.” Arriving in 1845, Israel Leavitt was the first Jewish arrival to Jefferson, where he opened a tavern. Soon after an influx of immigrants followed, looking to take advantage of Jefferson’s growing prosperity. By 1860, 38 percent of Jefferson’s residents were foreign born, a significant number of them Jewish.

Incorporated in 1848, the town was perfectly located at the intersection of a steamboat port and early wagon routes. By 1850, the population had boomed to just over 2,000, of which, according to one estimate, 8% were Jews. Jefferson became a thriving commercial center, in which Jews played a crucial role, until 1873, when various factors led to its decline. The earliest Jewish settlers in Jefferson were German immigrants who clustered in homes along Houston Street in the southwestern part of the city. Thereafter, residents referred to the area as “Jew Town” or the “Jewish Section.” Arriving in 1845, Israel Leavitt was the first Jewish arrival to Jefferson, where he opened a tavern. Soon after an influx of immigrants followed, looking to take advantage of Jefferson’s growing prosperity. By 1860, 38 percent of Jefferson’s residents were foreign born, a significant number of them Jewish.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Jefferson

Interior of Hebrew Sinai Congregation,

Interior of Hebrew Sinai Congregation, now used as a community theater

Early Settlers

Previously a merchant in McKinney, German-born Jacob Sterne settled in Jefferson with his wife Ernestine in 1855. He opened his own store, Gentleman’s Furnishing Goods, in both Jefferson and the nearby town of Marshall. In addition, Sterne worked in the county clerk’s office and was appointed Postmaster, a prestigious position at the time. When he died in 1872, his wife took over his position as Postmistress of Jefferson. Charles Wessolowsky, in his writings chronicling his visits to Southern Jewish cities, noted that her work served “to the great satisfaction and gratification of all.” Though he stated he was not a fan of President Rutherford B. Hayes, Wessolowsky considered his decision to entrust the job to Ernestine as “perhaps the wisest in his official career.”

As the Civil War divided the country, Jefferson contributed to the 105 Jewish Texans who fought on behalf of the Confederacy, among them Mark Pinksi, J. Nussbaum, James M. Jacobs and Gus Leavitt. Others contributed to the cause while not directly fighting. Jacob Sterne, who acquired a substitute service release, served as a quartermaster instead. He worked for the Confederate Clothing Depot, traveling to destinations east of the Mississippi River to purchase supplies for the armies. Jewish immigration to Jefferson slowed due to the war, with only five new merchants reaching the town during its years.

Previously a merchant in McKinney, German-born Jacob Sterne settled in Jefferson with his wife Ernestine in 1855. He opened his own store, Gentleman’s Furnishing Goods, in both Jefferson and the nearby town of Marshall. In addition, Sterne worked in the county clerk’s office and was appointed Postmaster, a prestigious position at the time. When he died in 1872, his wife took over his position as Postmistress of Jefferson. Charles Wessolowsky, in his writings chronicling his visits to Southern Jewish cities, noted that her work served “to the great satisfaction and gratification of all.” Though he stated he was not a fan of President Rutherford B. Hayes, Wessolowsky considered his decision to entrust the job to Ernestine as “perhaps the wisest in his official career.”

As the Civil War divided the country, Jefferson contributed to the 105 Jewish Texans who fought on behalf of the Confederacy, among them Mark Pinksi, J. Nussbaum, James M. Jacobs and Gus Leavitt. Others contributed to the cause while not directly fighting. Jacob Sterne, who acquired a substitute service release, served as a quartermaster instead. He worked for the Confederate Clothing Depot, traveling to destinations east of the Mississippi River to purchase supplies for the armies. Jewish immigration to Jefferson slowed due to the war, with only five new merchants reaching the town during its years.

After the Civil War

After the Confederacy’s surrender in 1865, Jefferson’s Jews experienced a period of growth and success, one that reflected the city’s own expansion as a commercial center. Jews descended upon Jefferson as the war ended, increasing their numbers to 138 households.

While still in Jefferson during the war, Sterne and Isaac Pinksi helped organize its Hebrew Benevolent Association in May 1862, with Pinksi as its first president. In 1866, the Society founded the state’s fourth-oldest Jewish cemetery, Mt. Sinai, a one-acre plot of land next to the city’s non-sectarian Oakwood Cemetery.

Jewish businesses were thriving, with dry goods stores, confectioneries and liquor stores being their most common establishments. Morris Cohn, M.J. Frankenthal and N.A. Jacobs all operated dry goods stores, while H. Mays owned a confectionery shop. According to the local tax ledger, Frederick Stutz and C. Browdowski sold liquor “by the quart,” Henry Goldwater “by the drink,” B. and H.T. Dreyfus “wholesale,” and Jacobs and Dimetry “by the pint.” The Big Fire of 1868 destroyed much of Jefferson’s commercial district. Of the nine businesses that sustained over $25,000 in damages, four were Jewish-owned. The district was quickly rebuilt, and, between 1870 and 1873, the city’s population doubled, reaching its peak of about 8,000 residents and becoming the fourth largest city in Texas. Twenty-six percent of all Jefferson merchants were Jewish, operating more than a quarter of Jefferson’s 300 businesses.

After the Confederacy’s surrender in 1865, Jefferson’s Jews experienced a period of growth and success, one that reflected the city’s own expansion as a commercial center. Jews descended upon Jefferson as the war ended, increasing their numbers to 138 households.

While still in Jefferson during the war, Sterne and Isaac Pinksi helped organize its Hebrew Benevolent Association in May 1862, with Pinksi as its first president. In 1866, the Society founded the state’s fourth-oldest Jewish cemetery, Mt. Sinai, a one-acre plot of land next to the city’s non-sectarian Oakwood Cemetery.

Jewish businesses were thriving, with dry goods stores, confectioneries and liquor stores being their most common establishments. Morris Cohn, M.J. Frankenthal and N.A. Jacobs all operated dry goods stores, while H. Mays owned a confectionery shop. According to the local tax ledger, Frederick Stutz and C. Browdowski sold liquor “by the quart,” Henry Goldwater “by the drink,” B. and H.T. Dreyfus “wholesale,” and Jacobs and Dimetry “by the pint.” The Big Fire of 1868 destroyed much of Jefferson’s commercial district. Of the nine businesses that sustained over $25,000 in damages, four were Jewish-owned. The district was quickly rebuilt, and, between 1870 and 1873, the city’s population doubled, reaching its peak of about 8,000 residents and becoming the fourth largest city in Texas. Twenty-six percent of all Jefferson merchants were Jewish, operating more than a quarter of Jefferson’s 300 businesses.

Mt. Sinai Cemetry, founded in 1866

Mt. Sinai Cemetry, founded in 1866

Organized Jewish Life in Jefferson

As Jefferson prospered, the Jewish community formed the Hebrew Sinai congregation in 1873. Initially without a synagogue or a rabbi, Hebrew Sinai quickly embraced Reform, mandating the use of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise’s Minhag America prayer book in its founding constitution. Yet the congregation must have anticipated conflict over matters of ritual and practice since the constitution also decreed that disputes over Hebrew law should be sent to the highest Jewish authorities in the United States or Europe for judgment. Interestingly, when they had a question over whether an uncircumcised child could be legally buried in the Jewish cemetery in 1873, they sent the question to Rabbi Wise, the father of Reform Judaism in America. Hebrew Sinai elected officers, with Eduard Eberstadt serving as its first president.

With the founding of Hebrew Sinai, it appeared that Jefferson was poised to become one of the largest and most thriving Jewish communities in Texas. However, two developments occurred in 1873 that drastically changed Jefferson’s future and that of its Jewish community. The federal government demolished the Red River raft – a natural dam that made steamboat travel to Jefferson possible – resulting in water levels too low for substantial steamboat commerce to continue. In addition, 1873 saw the completion of the Texas and Pacific Railroad, connecting Texarkana to Marshall while completely bypassing Jefferson, bringing an end to the city’s importance as a shipping center

As Jefferson prospered, the Jewish community formed the Hebrew Sinai congregation in 1873. Initially without a synagogue or a rabbi, Hebrew Sinai quickly embraced Reform, mandating the use of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise’s Minhag America prayer book in its founding constitution. Yet the congregation must have anticipated conflict over matters of ritual and practice since the constitution also decreed that disputes over Hebrew law should be sent to the highest Jewish authorities in the United States or Europe for judgment. Interestingly, when they had a question over whether an uncircumcised child could be legally buried in the Jewish cemetery in 1873, they sent the question to Rabbi Wise, the father of Reform Judaism in America. Hebrew Sinai elected officers, with Eduard Eberstadt serving as its first president.

With the founding of Hebrew Sinai, it appeared that Jefferson was poised to become one of the largest and most thriving Jewish communities in Texas. However, two developments occurred in 1873 that drastically changed Jefferson’s future and that of its Jewish community. The federal government demolished the Red River raft – a natural dam that made steamboat travel to Jefferson possible – resulting in water levels too low for substantial steamboat commerce to continue. In addition, 1873 saw the completion of the Texas and Pacific Railroad, connecting Texarkana to Marshall while completely bypassing Jefferson, bringing an end to the city’s importance as a shipping center

Hebrew Sinai Congregation's synagogue

Hebrew Sinai Congregation's synagogue

Still, the Jewish community remained active in Jefferson – for the time being. In November, 1875 the community finally purchased a synagogue for $2,000 on the corner of Market and Henderson Streets. The building had been constructed in 1860 as the home for Jefferson resident Robert Nesmith. Nesmith then sold it to the Catholic church in 1869, to be used as a convent, hospital and school. By 1875, without sufficient numbers of students or patients to continue, the church sold the property to the Jewish congregation. With the construction of an additional section the following year, the building became the Hebrew Sinai Congregation, providing Jefferson with its first synagogue. In August 1879, the congregation hired Rabbi Aaron Suhler, an 1872 German immigrant who had previously served at Dallas’ Temple Emanu-El. At this time, with Jefferson having a larger population than Dallas, it was considered a promotion.

"Diamond Bessie" and Abe Rothschild

"Diamond Bessie" and Abe Rothschild

A Scandal in Jefferson

Around this time, a sensational murder and subsequent trial consumed the town of Jefferson. On Friday, January 19, 1877, a young couple checked into the Brooks Hotel, giving the name “A. Monroe and wife.” The woman, who reportedly was covered with diamonds, was Diamond Bessie, a Syracuse-born prostitute actually named Annie Stone. With her was Abraham Rothschild, the son of a prominent and wealthy Jewish jewelry family from Cincinnati. The couple would last be seen together on Sunday morning as they left the hotel for a picnic. Later that day, Rothschild was seen in town without his companion. With various inquiries of Bessie’s whereabouts, he explained that she was visiting friends. By Tuesday, he had left Jefferson, without any appearance of Bessie since Sunday morning.

Two weeks later, after Jefferson had been blanketed with snow and sleet, a woman found the body of the then unidentified Diamond Bessie, who had been shot in the head. Moved by the youth and beauty of the anonymous murder victim, Jefferson’s residents collected $150 to pay for a proper burial, and two days after her discovery, Bessie was interred at Oakwood Cemetery. Jefferson officials issued a warrant for A. Monroe, who, of course, could not be found. Upon investigation, they discovered the true identity of the suspect and issued a new warrant for Abraham Rothschild. According to the Dallas Weekly Herald, Jefferson’s residents were deeply invested in the case, believing that “hanging is almost too good for the woman murderer, and that a slow fire should be started under him.”

While in a Cincinnati hospital recovering from a suicide attempt, Rothschild was located and arrested. Upon extradition, Rothschild was brought to Jefferson to await trial for the murder of Diamond Bessie. His family hired the best counsel available, which included U.S. Representative David B. Culberson and future Texas governor Charles A. Culberson. On grounds that no impartial jury members could be found in Jefferson, the trial was moved to Marshall. On December 24, 1878, after long delays, the first of Rothschild’s verdicts were decided: he was guilty of murder in the first degree and was sentenced to death by hanging. However, an error resulted in a new trial, taking place in Jefferson in December 1880. The verdict in this trial was different: not guilty. That night, Rothschild returned to Cincinnati, never to be seen in Jefferson again. Conspiracy theories followed, including the tale that twelve $1,000 bills were secretly passed down through the ceiling of the jury deliberation room. Though his religion was never a major issue, Rothschild was still viewed by the people of Jefferson as, “one of the vilest and meanest” men who got away with murder.

Around this time, a sensational murder and subsequent trial consumed the town of Jefferson. On Friday, January 19, 1877, a young couple checked into the Brooks Hotel, giving the name “A. Monroe and wife.” The woman, who reportedly was covered with diamonds, was Diamond Bessie, a Syracuse-born prostitute actually named Annie Stone. With her was Abraham Rothschild, the son of a prominent and wealthy Jewish jewelry family from Cincinnati. The couple would last be seen together on Sunday morning as they left the hotel for a picnic. Later that day, Rothschild was seen in town without his companion. With various inquiries of Bessie’s whereabouts, he explained that she was visiting friends. By Tuesday, he had left Jefferson, without any appearance of Bessie since Sunday morning.

Two weeks later, after Jefferson had been blanketed with snow and sleet, a woman found the body of the then unidentified Diamond Bessie, who had been shot in the head. Moved by the youth and beauty of the anonymous murder victim, Jefferson’s residents collected $150 to pay for a proper burial, and two days after her discovery, Bessie was interred at Oakwood Cemetery. Jefferson officials issued a warrant for A. Monroe, who, of course, could not be found. Upon investigation, they discovered the true identity of the suspect and issued a new warrant for Abraham Rothschild. According to the Dallas Weekly Herald, Jefferson’s residents were deeply invested in the case, believing that “hanging is almost too good for the woman murderer, and that a slow fire should be started under him.”

While in a Cincinnati hospital recovering from a suicide attempt, Rothschild was located and arrested. Upon extradition, Rothschild was brought to Jefferson to await trial for the murder of Diamond Bessie. His family hired the best counsel available, which included U.S. Representative David B. Culberson and future Texas governor Charles A. Culberson. On grounds that no impartial jury members could be found in Jefferson, the trial was moved to Marshall. On December 24, 1878, after long delays, the first of Rothschild’s verdicts were decided: he was guilty of murder in the first degree and was sentenced to death by hanging. However, an error resulted in a new trial, taking place in Jefferson in December 1880. The verdict in this trial was different: not guilty. That night, Rothschild returned to Cincinnati, never to be seen in Jefferson again. Conspiracy theories followed, including the tale that twelve $1,000 bills were secretly passed down through the ceiling of the jury deliberation room. Though his religion was never a major issue, Rothschild was still viewed by the people of Jefferson as, “one of the vilest and meanest” men who got away with murder.

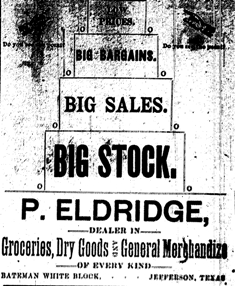

1890 ad for Phlip Eldridge's store

1890 ad for Phlip Eldridge's store

Though Jefferson’s Jewish population was continually declining after the turn of the century, it is important to note that they were always held in high regard among Jefferson’s residents. Gustav Frank II recalled that “during some very lean years our Hebrew friends would hold services only on some special occasion as they did not have a resident rabbi. On a number of occasions we Gentiles would get up a fair sized crowd and attend the Jewish service to help fill up the synagogue and supply a nice sized congregation for the Rabbi, who was generally one of some distinction.” Another indication was the closing of 81 businesses (with only four Jewish-owned ones, at this time) for the June 1923 funeral of Jewish merchant Isaiah L. Goldberg.

Goldberg’s sister, Jeanette, was a prominent Jewish figure from Jefferson. In 1893, she was instrumental in founding the Jewish Chautauqua Society, organized “for the dissemination of knowledge of the Jewish religion.” She served as field secretary for the group from 1905 to 1910, then as executive secretary from 1910 until her death in 1935. In addition, she worked as the National Field Secretary for the Council of Jewish Women. A plaque on the old Hebrew Sinai Congregation says, “Of Judaism, she was the high priestess"

The Sterne family also remained in Jefferson during its decline. Jacob and Ernestine’s children gave back to the city with the 1913 donation of the Sterne Memorial Fountain. Made of pure bronze and 13 and a half feet high, it celebrated Jefferson as the city that shaped their family. The inscription reads: “In this gift of the splendid piece of work lay the lifetime of a little immigrant girl grown to womanhood and the gratitude of her children to a little city that had given Mother and Father happiness.”

Goldberg’s sister, Jeanette, was a prominent Jewish figure from Jefferson. In 1893, she was instrumental in founding the Jewish Chautauqua Society, organized “for the dissemination of knowledge of the Jewish religion.” She served as field secretary for the group from 1905 to 1910, then as executive secretary from 1910 until her death in 1935. In addition, she worked as the National Field Secretary for the Council of Jewish Women. A plaque on the old Hebrew Sinai Congregation says, “Of Judaism, she was the high priestess"

The Sterne family also remained in Jefferson during its decline. Jacob and Ernestine’s children gave back to the city with the 1913 donation of the Sterne Memorial Fountain. Made of pure bronze and 13 and a half feet high, it celebrated Jefferson as the city that shaped their family. The inscription reads: “In this gift of the splendid piece of work lay the lifetime of a little immigrant girl grown to womanhood and the gratitude of her children to a little city that had given Mother and Father happiness.”

Sterne Memorial Fountain

Sterne Memorial Fountain

The Community Declines

While the Diamond Bessie murder case brought fame to Jefferson, the community could not escape the devastating events of 1873. By 1880, most inhabitants, including Jews, had left Jefferson for better opportunities in up and coming cities like Marshall and Dallas. With the dramatic decline of the Jewish congregation, Rabbi Suhler left in 1883 to return to Dallas. At the end of the decade, Jefferson’s population had sunk to 1,331, with only 26 Jewish households remaining.

Still, Jews who stayed in Jefferson prospered. Wessolowsky noted K. Mendel and Co., a wholesale house “doing business by the millions and is indeed a pride and honor to any city.” He also noted that Jefferson’s Jews had “entire control of the mercantile business.” Philip Eldridge operated a dry goods store, Uriah P. Levy a jewelry store, Julius Ney a furniture business, Max Rosenfeld a general merchandise shop, and Eduard Eberstadt a grocery business, among others. Elbert C. Wise, a Jefferson resident, remembered that in 1900, Jewish businesses “owned almost every store in (downtown) Jefferson.”

While the Diamond Bessie murder case brought fame to Jefferson, the community could not escape the devastating events of 1873. By 1880, most inhabitants, including Jews, had left Jefferson for better opportunities in up and coming cities like Marshall and Dallas. With the dramatic decline of the Jewish congregation, Rabbi Suhler left in 1883 to return to Dallas. At the end of the decade, Jefferson’s population had sunk to 1,331, with only 26 Jewish households remaining.

Still, Jews who stayed in Jefferson prospered. Wessolowsky noted K. Mendel and Co., a wholesale house “doing business by the millions and is indeed a pride and honor to any city.” He also noted that Jefferson’s Jews had “entire control of the mercantile business.” Philip Eldridge operated a dry goods store, Uriah P. Levy a jewelry store, Julius Ney a furniture business, Max Rosenfeld a general merchandise shop, and Eduard Eberstadt a grocery business, among others. Elbert C. Wise, a Jefferson resident, remembered that in 1900, Jewish businesses “owned almost every store in (downtown) Jefferson.”

The Jewish Community in Jefferson Today

The Sterne Memorial Fountain still stands today at the intersection of Market and Lafayette Streets. With no funds to support a rabbi after Suhler’s departure, Philip Eldridge conducted services for the Hebrew Sinai Congregation. After his death in 1927, services ceased, and the state of the building deteriorated. In 1964, the Jessie Allen Wise Garden Club, through their Excelsior Foundation, purchased the property in an effort to restore the historic structure. Now called the Jefferson Playhouse, the former synagogue is used to present the annual play “The Diamond Bessie Murder Trial.” Money from the sale of the synagogue, as well as from the Kaleski Estate, is used to maintain the Mt. Sinai Cemetery.

As Jefferson’s general population continued to decrease, sinking to 3,203 residents in 1970 and 2,024 in 2000, so did its Jewish population. After Eva Eberstadt died in 1974, only one Jew, Lille Lipman, remained. Like so many others, she relocated to Dallas in 1980, ending the Jewish presence in Jefferson.

As Jefferson’s general population continued to decrease, sinking to 3,203 residents in 1970 and 2,024 in 2000, so did its Jewish population. After Eva Eberstadt died in 1974, only one Jew, Lille Lipman, remained. Like so many others, she relocated to Dallas in 1980, ending the Jewish presence in Jefferson.