Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Lockhart, Texas

Lockhart: Historical Overview

In 1901, most of Lockhart turned out to watch the town’s parade marking the 65th anniversary of Texas independence. Local merchants took part in the festivities, creating floats that represented their businesses. Lockhart’s small number of Jewish store owners enthusiastically joined in. Leo Schwartz recreated his dry goods store on his float, which won a top prize. Sam Lissner, according to the local newspaper, had “a unique representation of his grocery business.” Rudolph Warshawski entered two floats in the parade: one showing the modest beginning of his dry goods store, with the second depicting its current state. This Jewish involvement reflected their central economic role as well as their integration within local society. While the parade expressed an optimism that Lockhart would grow and flourish in the new century, its Jewish community would never become large enough to establish lasting Jewish institutions. Nevertheless, a small number of Jewish families have had a significant impact on this small central Texas town.

When Caldwell County was established in 1848, a small village named after land surveyor Byrd Lockhart became its seat. Officially incorporated in 1852, Lockhart did not begin to develop economically until the late 1860s when the town became a stop along the Chisolm cattle trail. Still, its growth was slow for the next two decades until a railroad line was finally built into Lockhart in 1887. By the turn of the century, Lockhart was a small regional commercial and processing center for the area’s cotton crop. According to the 1900 census, 2,300 people lived in the town.

When Caldwell County was established in 1848, a small village named after land surveyor Byrd Lockhart became its seat. Officially incorporated in 1852, Lockhart did not begin to develop economically until the late 1860s when the town became a stop along the Chisolm cattle trail. Still, its growth was slow for the next two decades until a railroad line was finally built into Lockhart in 1887. By the turn of the century, Lockhart was a small regional commercial and processing center for the area’s cotton crop. According to the 1900 census, 2,300 people lived in the town.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Lockhart

Early Settlers

The first Jews to settle in Lockhart were drawn to the new town’s economic potential due to its location on the new cattle trail. Jacob Halfin, who had left Bavaria in 1852, lived in Gonzales, Texas, in 1860. After the Civil War, Halfin moved to Lockhart with his wife Sarah and their five children, and opened a store. Halfin enjoyed economic success, owning $3,500 in personal estate by the time of the 1870 census. His younger brother or cousin, Eli Halfin, lived with the family in 1870, and worked in the business with Jacob. The Halfins were likely the only Jewish family to live in Lockhart until the 1890s.

Only after the railroad came to Lockhart did the town attract a significant number of Jewish settlers. A handful opened stores in Lockhart during the 1890s. Rudolph Warshawski left Poland as a child in 1861. He moved to Lockhart in 1892 with his wife Helena and three daughters and opened a dry goods store on the downtown square. Leo Schwarz left Germany in 1873, settling in Texas by 1886. In 1898, he moved to Lockhart and opened a dry goods store, which remained in the business until the 1920s.

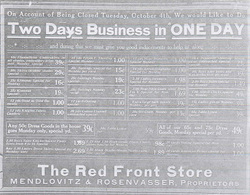

Morris Rosenwasser left Hungary for New York City in 1890. He soon traveled south as a peddler, spending time in West Texas before moving to Lockhart in the late 1890s. Rosenwasser was well suited to peddling in central Texas as his fluency in German and Polish enabled him to communicate with the immigrant farmers of the area. While on a buying trip in New York, Rosenwasser met Annie Freedman, whom he married in 1901. The couple settled in Lockhart, where Morris opened The Red Front Store with another Jewish immigrant, Aaron Mendlovitz, in 1902. Later known as Rosenwasser’s, the store moved to a new larger location in 1914. Morris also ran a wholesale operation, supplying merchandise on credit to peddlers who traveled central Texas.

The first Jews to settle in Lockhart were drawn to the new town’s economic potential due to its location on the new cattle trail. Jacob Halfin, who had left Bavaria in 1852, lived in Gonzales, Texas, in 1860. After the Civil War, Halfin moved to Lockhart with his wife Sarah and their five children, and opened a store. Halfin enjoyed economic success, owning $3,500 in personal estate by the time of the 1870 census. His younger brother or cousin, Eli Halfin, lived with the family in 1870, and worked in the business with Jacob. The Halfins were likely the only Jewish family to live in Lockhart until the 1890s.

Only after the railroad came to Lockhart did the town attract a significant number of Jewish settlers. A handful opened stores in Lockhart during the 1890s. Rudolph Warshawski left Poland as a child in 1861. He moved to Lockhart in 1892 with his wife Helena and three daughters and opened a dry goods store on the downtown square. Leo Schwarz left Germany in 1873, settling in Texas by 1886. In 1898, he moved to Lockhart and opened a dry goods store, which remained in the business until the 1920s.

Morris Rosenwasser left Hungary for New York City in 1890. He soon traveled south as a peddler, spending time in West Texas before moving to Lockhart in the late 1890s. Rosenwasser was well suited to peddling in central Texas as his fluency in German and Polish enabled him to communicate with the immigrant farmers of the area. While on a buying trip in New York, Rosenwasser met Annie Freedman, whom he married in 1901. The couple settled in Lockhart, where Morris opened The Red Front Store with another Jewish immigrant, Aaron Mendlovitz, in 1902. Later known as Rosenwasser’s, the store moved to a new larger location in 1914. Morris also ran a wholesale operation, supplying merchandise on credit to peddlers who traveled central Texas.

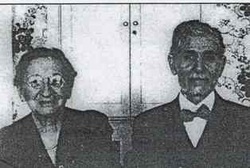

Mamie & Phillip Glosserman

Mamie & Phillip Glosserman

When Harry Pomerantz opened a tiny downtown fruit stand in 1899, little did he know that he was laying the foundation of Lockhart’s Jewish community for the next century. Harry Pomerantz opened this modest fruit business in the same building as a saloon, but sold it in 1905 to his brother-in-law Phillip Glosserman, who had left Tsarist Russia in 1900 to avoid being drafted in the army for a second time. Glosserman, who had left his wife and children in Europe, came to Seguin, Texas, where another brother-in-law Louis Pomerantz lived. Glosserman peddled in the area while his wife Mamie ran the grocery store they owned in Polish Russia. Finally, on Christmas Day in 1902, the family was reunited when Mamie and their two young sons Moses and Maurice arrived in Galveston. After Phillip bought the fruit stand in 1905, the family moved to Lockhart. When prohibition put the neighboring saloon out of business, Glosserman expanded the stand into a grocery and feed store. In 1919, he opened a dry goods store that was run by his sons Moses and Sam, while his son Maurice worked in the family’s grocery business. Phillip embraced his adopted country, often using the phrase, “only in America” to describe his life. The Glosserman family would become pillars of the Lockhart business community and a large part of the town’s small Jewish population.

Organized Jewish Life in Lockhart

The arrival of Phillip Glosserman, who had studied at a yeshiva in Europe, was a catalyst in the religious development of the Lockhart Jewish community. After Glosserman moved to town, local Jews began to meet together for the High Holidays. In 1910, ten Jewish families established a congregation, Beth Sholem. The group met initially on the second floor of the Vogel Building, with Glosserman leading the services. According to the local newspaper in 1910, the congregation’s High Holiday services attracted many Jews from surrounding towns. By 1922, the congregation held regular Shabbat services in addition to the High Holidays. Its weekly religious school had 37 students that year. For Rosh Hashanah, the congregation brought down University of Texas math professor Dr. Hyman Ettlinger to lead services. Later, the congregation met on the second floor of Scheels Drugstore, which was outfitted as a small synagogue, with a Torah, owned by Phillip Glosserman, and an organ. Their services were a mix of traditional and Reform, with Hebrew prayers led by Glosserman, English prayers led by Albert Weinbaum, mixed-gender seating, and organ music. The congregation, which had between 15 and 18 member families at its peak, never affiliated with a national movement.

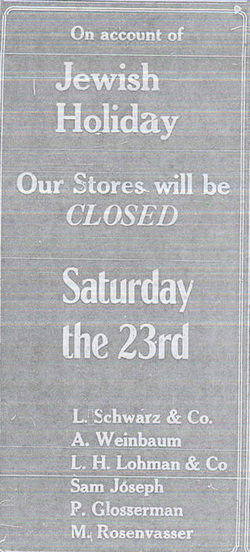

Beth Sholem was short-lived, never growing large enough to support a permanent synagogue. By the 1930s, services were only held on the High Holidays, which were still led by Phillip Glosserman and Weinbaum. According to a report in the local newspaper, 65 people attended the congregation’s Rosh Hashanah service in 1935, many from surrounding towns like Luling and Seguin. The newspaper encouraged local Christians to read the portion of their bible about the upcoming holiday of Yom Kippur “for verily all of our religion comes out of the Jewish nation.” By the end of the 1930s, the congregation had become defunct with its religious school disbanded. Although Beth Sholem was no longer active, local Jews still observed the High Holidays, closing their stores and driving to Austin or San Antonio for services, which was abetted by new improved roads. Lockhart’s Jewish community shrunk from 80 to 50 people between 1927 and 1937, which was the likely cause for Beth Sholem’s demise.

Despite the decline of their congregation, Lockhart Jews established a chapter of the Jewish fraternal society B’nai B’rith in 1941 with Jews from other towns in the area, such as Luling, Seguin, New Braunfels, and Gonzales. During World War II, the lodge worked with the USO at nearby Camp Gary to host and entertain Jewish troops stationed there. At its peak, the B’nai Bridge lodge had 44 members, with most coming from Seguin and Lockhart. The lodge remained active into the 1960s, when it had 32 members. Seguin had a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women to which several Lockhart Jews belonged.

The arrival of Phillip Glosserman, who had studied at a yeshiva in Europe, was a catalyst in the religious development of the Lockhart Jewish community. After Glosserman moved to town, local Jews began to meet together for the High Holidays. In 1910, ten Jewish families established a congregation, Beth Sholem. The group met initially on the second floor of the Vogel Building, with Glosserman leading the services. According to the local newspaper in 1910, the congregation’s High Holiday services attracted many Jews from surrounding towns. By 1922, the congregation held regular Shabbat services in addition to the High Holidays. Its weekly religious school had 37 students that year. For Rosh Hashanah, the congregation brought down University of Texas math professor Dr. Hyman Ettlinger to lead services. Later, the congregation met on the second floor of Scheels Drugstore, which was outfitted as a small synagogue, with a Torah, owned by Phillip Glosserman, and an organ. Their services were a mix of traditional and Reform, with Hebrew prayers led by Glosserman, English prayers led by Albert Weinbaum, mixed-gender seating, and organ music. The congregation, which had between 15 and 18 member families at its peak, never affiliated with a national movement.

Beth Sholem was short-lived, never growing large enough to support a permanent synagogue. By the 1930s, services were only held on the High Holidays, which were still led by Phillip Glosserman and Weinbaum. According to a report in the local newspaper, 65 people attended the congregation’s Rosh Hashanah service in 1935, many from surrounding towns like Luling and Seguin. The newspaper encouraged local Christians to read the portion of their bible about the upcoming holiday of Yom Kippur “for verily all of our religion comes out of the Jewish nation.” By the end of the 1930s, the congregation had become defunct with its religious school disbanded. Although Beth Sholem was no longer active, local Jews still observed the High Holidays, closing their stores and driving to Austin or San Antonio for services, which was abetted by new improved roads. Lockhart’s Jewish community shrunk from 80 to 50 people between 1927 and 1937, which was the likely cause for Beth Sholem’s demise.

Despite the decline of their congregation, Lockhart Jews established a chapter of the Jewish fraternal society B’nai B’rith in 1941 with Jews from other towns in the area, such as Luling, Seguin, New Braunfels, and Gonzales. During World War II, the lodge worked with the USO at nearby Camp Gary to host and entertain Jewish troops stationed there. At its peak, the B’nai Bridge lodge had 44 members, with most coming from Seguin and Lockhart. The lodge remained active into the 1960s, when it had 32 members. Seguin had a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women to which several Lockhart Jews belonged.

The sign for Glosserman's Clothing

The sign for Glosserman's Clothing store is still visible today

Jewish Businesses in Lockhart

Although the Lockhart Jewish community was small, its influence on the local economy was significant. Lockhart Jews remained concentrated in retail trade and their clothing and dry goods stores lined the streets of the town’s courthouse square. In 1910, these stores included: Sam Joseph, A. Weinbaum, the Red Front Store, which was owned by Mendlovitz and Rosenwasser, The Grand Leader, which was owned by Rudolph Warshawski and Seymour Lissner, L. Schwarz & Co., and Jared J. Lissner. These stores often advertised that their goods were the newest and most fashionable; both the Red Front Store and L. Schwarz and Co. noted in their ads that their owners had traveled to Eastern markets and brought back the most up-to-date fashions.

Several of the children of Lockhart’s early Jewish merchants remained in town to take over and expand their family businesses. Morris Rosenwasser’s sons Gershon and Isadore joined their father in the store, taking it over after he died in 1936. Isadore ran Rosenwasser’s until he sold the business and retired in 1979. Rudolph’s daughter, Blanche Warshawski, married Lee Lohman, and opened a clothing store on the square in 1921. After Lee died, Blanche Lohman continued to run the business. In her later years, she would close the store and go home whenever she felt like it, claiming that if a customer needed something, they knew where to find her. Blanche often claimed that she grew up on the courthouse square. She continued to visit the businesses there regularly after she closed her own store in 1968.

Phillip Glosserman’s children learned how to run a business at an early age. By age five, Sam Glosserman would sell his father’s roasted peanuts all around town. When he was six, Sam was selling copies of the Houston Chronicle newspaper. Sam,along with his older brothers Moses and Maurice, joined his father’s grocery and dry goods businesses. In 1929, the three brothers opened the Motor Sales Company, which sold General Motors cars, though the business struggled in its early years due to the Great Depression. Moses ran the business initially, while Sam ran the family dry goods store, Glosserman’s, and Maurice worked with their father in the grocery business. The family owned all three businesses jointly. The car dealership, later known as Glosserman Chevrolet, thrived during the war years, even though they were no new cars to sell at the time. Moses Glosserman traveled east, buying any used car he could fine, and brought them back to Lockhart to sell. He also sold school buses to districts around the country. After Phillip Glosserman died in 1949, Maurice joined the dealership after the family closed the grocery store. Sam Glosserman continued to run the clothing store until his death in 1990. Sam’s daughter Abbi Michelson then ran the store for another four years before closing it. She and her husband David had bought the car dealership in 1978 after Moses died. Today, her son Jeff Michelson and his wife Shelly run the business, which has been serving central Texas through 80 years and three generations of Glossermans.

Civic Engagement

Lockhart Jews, though they have always been a tiny fraction of the town’s population, have been very involved in the larger community and have made significant civic contributions. Morris Rosenwasser served as a volunteer fireman and often helped those in need, giving away clothes to area farmers during the boll weevil crisis of the 1900s. His son Gershon later served as vice president of the Caldwell County Centennial Association. Both Moses and Maurice Glosserman served terms as president of the Lockhart Chamber of Commerce. Moses spent 20 years as president of the Lockhart School Board and later served as head of the Texas Association of School Boards. He was also chairman of the board of the First Lockhart National Bank for 25 years. Sam Glosserman was elected mayor of Lockhart multiple times, serving for ten years during the 1950s. During his tenure, Glosserman oversaw the construction of a new city hall, which happened to be located on the same lot where he had been born in 1903. Jewish involvement in the larger community engendered tremendous respect. The Methodist owner of a local pharmacy, Edwin Westmoreland, would solicit donations for the United Jewish Appeal from other non-Jewish merchants in town and turn the money over to the Glossermans.

Although the Lockhart Jewish community was small, its influence on the local economy was significant. Lockhart Jews remained concentrated in retail trade and their clothing and dry goods stores lined the streets of the town’s courthouse square. In 1910, these stores included: Sam Joseph, A. Weinbaum, the Red Front Store, which was owned by Mendlovitz and Rosenwasser, The Grand Leader, which was owned by Rudolph Warshawski and Seymour Lissner, L. Schwarz & Co., and Jared J. Lissner. These stores often advertised that their goods were the newest and most fashionable; both the Red Front Store and L. Schwarz and Co. noted in their ads that their owners had traveled to Eastern markets and brought back the most up-to-date fashions.

Several of the children of Lockhart’s early Jewish merchants remained in town to take over and expand their family businesses. Morris Rosenwasser’s sons Gershon and Isadore joined their father in the store, taking it over after he died in 1936. Isadore ran Rosenwasser’s until he sold the business and retired in 1979. Rudolph’s daughter, Blanche Warshawski, married Lee Lohman, and opened a clothing store on the square in 1921. After Lee died, Blanche Lohman continued to run the business. In her later years, she would close the store and go home whenever she felt like it, claiming that if a customer needed something, they knew where to find her. Blanche often claimed that she grew up on the courthouse square. She continued to visit the businesses there regularly after she closed her own store in 1968.

Phillip Glosserman’s children learned how to run a business at an early age. By age five, Sam Glosserman would sell his father’s roasted peanuts all around town. When he was six, Sam was selling copies of the Houston Chronicle newspaper. Sam,along with his older brothers Moses and Maurice, joined his father’s grocery and dry goods businesses. In 1929, the three brothers opened the Motor Sales Company, which sold General Motors cars, though the business struggled in its early years due to the Great Depression. Moses ran the business initially, while Sam ran the family dry goods store, Glosserman’s, and Maurice worked with their father in the grocery business. The family owned all three businesses jointly. The car dealership, later known as Glosserman Chevrolet, thrived during the war years, even though they were no new cars to sell at the time. Moses Glosserman traveled east, buying any used car he could fine, and brought them back to Lockhart to sell. He also sold school buses to districts around the country. After Phillip Glosserman died in 1949, Maurice joined the dealership after the family closed the grocery store. Sam Glosserman continued to run the clothing store until his death in 1990. Sam’s daughter Abbi Michelson then ran the store for another four years before closing it. She and her husband David had bought the car dealership in 1978 after Moses died. Today, her son Jeff Michelson and his wife Shelly run the business, which has been serving central Texas through 80 years and three generations of Glossermans.

Civic Engagement

Lockhart Jews, though they have always been a tiny fraction of the town’s population, have been very involved in the larger community and have made significant civic contributions. Morris Rosenwasser served as a volunteer fireman and often helped those in need, giving away clothes to area farmers during the boll weevil crisis of the 1900s. His son Gershon later served as vice president of the Caldwell County Centennial Association. Both Moses and Maurice Glosserman served terms as president of the Lockhart Chamber of Commerce. Moses spent 20 years as president of the Lockhart School Board and later served as head of the Texas Association of School Boards. He was also chairman of the board of the First Lockhart National Bank for 25 years. Sam Glosserman was elected mayor of Lockhart multiple times, serving for ten years during the 1950s. During his tenure, Glosserman oversaw the construction of a new city hall, which happened to be located on the same lot where he had been born in 1903. Jewish involvement in the larger community engendered tremendous respect. The Methodist owner of a local pharmacy, Edwin Westmoreland, would solicit donations for the United Jewish Appeal from other non-Jewish merchants in town and turn the money over to the Glossermans.

The Jewish Community in Lockhart Today

By the mid-20th century, most of the Jewish children raised in Lockhart were moving away when they got older. When Abbi Glosserman, Sam’s daughter, was growing up in the 1940s and 1950s, there were few other Jewish children in Lockhart aside from her siblings and cousins. She attended Sunday school and later BBYO events in Austin. Her family belonged to the Reform congregations in both Austin and San Antonio. By 1972, only five Jewish families still lived in Lockhart. The town’s courthouse square was no longer lined with Jewish-owned stores. After Glosserman’s clothing store closed in 1994, none remained. In 2010, Abbi Glosserman Michelson and her son and daughter, who continue to run the Glosserman car dealership, were the last remaining Jews in town.