Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Lubbock, Texas

Lubbock: Historical Overview

|

Located in the south plains of West Texas, Lubbock was a small desolate settlement until the Santa Fe Railroad was built through the area in 1909. That same year the town was officially incorporated, though it had fewer than 2,000 residents by the time of the 1910 census. The town’s fate would be forever changed when the Texas Legislature created Texas Technological College in 1923, and decided to build it in Lubbock. In addition to hosting the college, which opened in 1926, Lubbock became a regional center for agriculture as irrigated cotton farming came to the south plains in the 1930s.

Lubbock also developed industry, often tied to its cash crop, becoming one of the largest producers of cottonseed oil in the world. As Lubbock began to grow in the early 20th century, a small number of Jews moved to town. Jews have been a part of the community in Lubbock ever since. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Lubbock

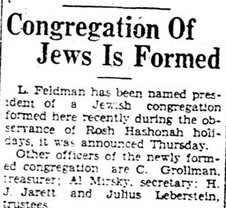

Article in Lubbock newspaper on Sept. 18, 1931

Article in Lubbock newspaper on Sept. 18, 1931

Early Settlers

Claude and Jennie Grollman were the first Jews in Lubbock, arriving in 1916 to open a dry goods store in the small town of 4,000 people. Both were born in Russia, and had spent about a decade in the U.S. before moving to Lubbock. They did not stay long, leaving town in 1920. During the 1920s, a growing number of Jews settled in Lubbock. When the Grollmans moved back to Lubbock in 1927, they found a much larger town of 15,000 people and a burgeoning Jewish community.

Most all of the Jewish families in Lubbock were involved in business, mainly retail trade. By 1928, Grollman owned a department store, while Isaac Cohn and Sam Koretzky had clothing stores. Louis Feldman owned a scrap metal business with Harry Leva. Morris Levine started Levine’s Department Store in downtown Lubbock in 1929. His brother William soon joined him to help run the business, which eventually grew into a regional chain. The Levines hired several Jews to work in the store, including Al Glassman, who became a store manager in 1933. The Levine brothers moved to Dallas after World War II, but kept the four-story department store open in Lubbock. The Levine family later sold the chain. Although there is still a Levine’s in Lubbock today, it is no longer owned by local Jews.

Claude and Jennie Grollman were the first Jews in Lubbock, arriving in 1916 to open a dry goods store in the small town of 4,000 people. Both were born in Russia, and had spent about a decade in the U.S. before moving to Lubbock. They did not stay long, leaving town in 1920. During the 1920s, a growing number of Jews settled in Lubbock. When the Grollmans moved back to Lubbock in 1927, they found a much larger town of 15,000 people and a burgeoning Jewish community.

Most all of the Jewish families in Lubbock were involved in business, mainly retail trade. By 1928, Grollman owned a department store, while Isaac Cohn and Sam Koretzky had clothing stores. Louis Feldman owned a scrap metal business with Harry Leva. Morris Levine started Levine’s Department Store in downtown Lubbock in 1929. His brother William soon joined him to help run the business, which eventually grew into a regional chain. The Levines hired several Jews to work in the store, including Al Glassman, who became a store manager in 1933. The Levine brothers moved to Dallas after World War II, but kept the four-story department store open in Lubbock. The Levine family later sold the chain. Although there is still a Levine’s in Lubbock today, it is no longer owned by local Jews.

Organized Jewish Life in Lubbock

By the end of the 1920s, this growing number of Jewish merchants began to organize as a community. In 1929, the Jews of Lubbock borrowed a Torah and held High Holiday services for the first time in a local hotel. The first formal organization was a social and charitable group established by 15 men in early 1931 with William Levine as its president. The local newspaper did not mention the name of the group, though since state Zionist leader Charles Bender helped to organize it, it may have been a Zionist society. Not much is known about this short-lived group.

Later in 1931, the Lubbock Morning Avalanche reported that local Jews had organized a congregation in time for the High Holidays with Louis Feldman as its president and Claude Grollman as treasurer. The group brought in a Rabbi Goldstein from Fort Worth to lead High Holiday services at the Hotel Lubbock. According to the newspaper, “the Jewish residents of Lubbock made plans for the purchase of a lot on which they hope to later erect a permanent meeting place for their members.” Despite these ambitious plans, the group did not meet regularly for services aside from the High Holidays.

Not until 1934 did Lubbock Jews establish a formal permanent congregation, which they named Shaareth Israel. According to the congregation’s original charter, Shaareth Israel was founded “for the purpose of supporting public worship according to the Orthodox ritual” and “to provide a Hebrew school and help the worthy poor.” Claude Grollman was named the first president of Shaareth Israel. The following year, the congregation bought a Torah; in 1937, they purchased a house on Avenue X which they remodeled into a synagogue.

By the end of the 1920s, this growing number of Jewish merchants began to organize as a community. In 1929, the Jews of Lubbock borrowed a Torah and held High Holiday services for the first time in a local hotel. The first formal organization was a social and charitable group established by 15 men in early 1931 with William Levine as its president. The local newspaper did not mention the name of the group, though since state Zionist leader Charles Bender helped to organize it, it may have been a Zionist society. Not much is known about this short-lived group.

Later in 1931, the Lubbock Morning Avalanche reported that local Jews had organized a congregation in time for the High Holidays with Louis Feldman as its president and Claude Grollman as treasurer. The group brought in a Rabbi Goldstein from Fort Worth to lead High Holiday services at the Hotel Lubbock. According to the newspaper, “the Jewish residents of Lubbock made plans for the purchase of a lot on which they hope to later erect a permanent meeting place for their members.” Despite these ambitious plans, the group did not meet regularly for services aside from the High Holidays.

Not until 1934 did Lubbock Jews establish a formal permanent congregation, which they named Shaareth Israel. According to the congregation’s original charter, Shaareth Israel was founded “for the purpose of supporting public worship according to the Orthodox ritual” and “to provide a Hebrew school and help the worthy poor.” Claude Grollman was named the first president of Shaareth Israel. The following year, the congregation bought a Torah; in 1937, they purchased a house on Avenue X which they remodeled into a synagogue.

Synagogue built by Shaareth Israel in 1943

Synagogue built by Shaareth Israel in 1943

The members of Shaareth Israel were immigrants who owned retail businesses. Several had lived in Lubbock for only a few years. Of Shaareth Israel’s nine founding officers and board members in 1934, four did not live in Lubbock in 1930. Of the five who were listed in the 1930 census, all of them were immigrants from Russia or Poland. Four of the five owned their own retail businesses, while the other managed a drug store. In 1939, all of the officers and directors of Shaareth Israel were merchants. During these early years, the Lubbock Jewish community was made up of a handful of extended families as many Lubbock Jews were related to each other. In addition, Shaareth Israel drew members from such small towns as Tahoka, Levelland, Slaton, and Portales, New Mexico.

In 1938, Shaareth Israel was able to hire a full-time rabbi, Isadore Garsek, who stayed with the congregation for the next ten years, though he spent two of them as a military chaplain during the war. Not long after the congregation formed, women established a ladies auxiliary; it changed its name to the Sisterhood around 1940. Shaareth Israel quickly outgrew its small house of worship. In 1943, it built a new synagogue on Avenue Q, designed by congregation member and architect Sam Kelisky, who had moved to Lubbock from Kansas City in 1937. When Louis Feldman was hit by a car and died in 1940, the congregation bought land for a burial ground within the city’s cemetery. In 1953, Shaareth Israel built an addition with five new classrooms and a social hall named for the Houstman family, who had donated much of the money for the project.

Although Shaareth Israel was Orthodox when it was founded, it soon moved away from traditional practice. By 1945, the congregation was nominally Reform, though in reality it was more of a hybrid between Reform and Conservative Judaism. Worshipers were still expected to wear head coverings in the sanctuary and women were not allowed to receive Torah honors until the 1980s. The congregation joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations by 1962. Shaareth Israel also hired Reform rabbis. Rabbi Julius Kerman replaced Rabbi Garsek in 1947, leading the Lubbock congregation for the next few years. He was replaced by Rabbi Adolph Phillipsborn, who stayed in Lubbock for only a few years. Rabbi Stanley Yedwab led Shaareth Israel from 1956 to 1959. These Reform rabbis sometimes got into trouble with their more traditional minded members. Rabbi Yedwab’s wife Myra shocked members when she submitted a recipe for pork chops for the Sisterhood cookbook. The congregation also insisted that its rabbis wear yarmulkes during services.

In 1938, Shaareth Israel was able to hire a full-time rabbi, Isadore Garsek, who stayed with the congregation for the next ten years, though he spent two of them as a military chaplain during the war. Not long after the congregation formed, women established a ladies auxiliary; it changed its name to the Sisterhood around 1940. Shaareth Israel quickly outgrew its small house of worship. In 1943, it built a new synagogue on Avenue Q, designed by congregation member and architect Sam Kelisky, who had moved to Lubbock from Kansas City in 1937. When Louis Feldman was hit by a car and died in 1940, the congregation bought land for a burial ground within the city’s cemetery. In 1953, Shaareth Israel built an addition with five new classrooms and a social hall named for the Houstman family, who had donated much of the money for the project.

Although Shaareth Israel was Orthodox when it was founded, it soon moved away from traditional practice. By 1945, the congregation was nominally Reform, though in reality it was more of a hybrid between Reform and Conservative Judaism. Worshipers were still expected to wear head coverings in the sanctuary and women were not allowed to receive Torah honors until the 1980s. The congregation joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations by 1962. Shaareth Israel also hired Reform rabbis. Rabbi Julius Kerman replaced Rabbi Garsek in 1947, leading the Lubbock congregation for the next few years. He was replaced by Rabbi Adolph Phillipsborn, who stayed in Lubbock for only a few years. Rabbi Stanley Yedwab led Shaareth Israel from 1956 to 1959. These Reform rabbis sometimes got into trouble with their more traditional minded members. Rabbi Yedwab’s wife Myra shocked members when she submitted a recipe for pork chops for the Sisterhood cookbook. The congregation also insisted that its rabbis wear yarmulkes during services.

Rabbi Julius Kerman

Rabbi Julius Kerman

Zionism in Lubbock

When Rabbi Kerman came to Lubbock in 1948, he pushed local Jews to establish a Zionist organization. Called the Lubbock Zionist District, the group affiliated with the Zionist Association of America. Rabbi Kerman served as president of the group for its first two years. The group held monthly meetings with guest speakers and documentary films from Israel; each meeting ended with the singing of “Hatikvah,” the Israeli national anthem. The Lubbock Zionist District worked to raise money for various causes in the fledgling Jewish state. By the end of 1950, the group had 71 members, with seventeen living in other west Texas towns. By 1951, the group had become largely inactive, as the initial thrill of Israel’s founding and victory in the War of Independence faded. When Rabbi Kerman left Lubbock in 1952, the group decided to disband. The demise of the Lubbock Zionist District did not mark the end of active Zionism in the city. A chapter of Hadassah had been founded in 1949 due to the efforts of Ida Ruth Swidlow. An attempt to establish a chapter a decade earlier failed as Lubbock’s Jewish women feared that the community was not large enough to support it in addition to the Sisterhood. Ethel Freed served as the first president of the chapter, which remained active until around 1990.

When Rabbi Kerman came to Lubbock in 1948, he pushed local Jews to establish a Zionist organization. Called the Lubbock Zionist District, the group affiliated with the Zionist Association of America. Rabbi Kerman served as president of the group for its first two years. The group held monthly meetings with guest speakers and documentary films from Israel; each meeting ended with the singing of “Hatikvah,” the Israeli national anthem. The Lubbock Zionist District worked to raise money for various causes in the fledgling Jewish state. By the end of 1950, the group had 71 members, with seventeen living in other west Texas towns. By 1951, the group had become largely inactive, as the initial thrill of Israel’s founding and victory in the War of Independence faded. When Rabbi Kerman left Lubbock in 1952, the group decided to disband. The demise of the Lubbock Zionist District did not mark the end of active Zionism in the city. A chapter of Hadassah had been founded in 1949 due to the efforts of Ida Ruth Swidlow. An attempt to establish a chapter a decade earlier failed as Lubbock’s Jewish women feared that the community was not large enough to support it in addition to the Sisterhood. Ethel Freed served as the first president of the chapter, which remained active until around 1990.

Rabbi Alexander Kline

Rabbi Alexander Kline

The Post-War Era

Lubbock grew into a major city during the post-war years. Between 1940 and 1960, Lubbock’s population increased from 32,000 to 128,000 people. Reese Air Force Base, built during World War II, was an important part of this growth. The Jewish community grew significantly as well, from 60 Jews in 1937 to 212 in 1948. They continued to concentrate in retail trade. Of Shaareth Israel’s 12 board members in 1952, all but two owned retail businesses, primarily clothing stores. Albert Skibell moved to Lubbock after the war and bought Grollman’s clothing store, renaming it Albert’s House of Fashion. His brother Archie opened Skibell’s, another women’s clothing store, in Lubbock after the war. In 1958, the brothers merged their businesses, and built Skibell’s into a small chain that had nine stores across Texas. Albert’s son Charles later ran the business, before closing the last store in 2001.

Shaareth Israel flourished along with the rest of the city. In 1960, the congregation hired Rabbi Alexander Kline from Clarksdale, Mississippi. A native of Hungary, Kline was an art lover and expert, and gave many lectures on art history at the Texas Tech Museum using his personal collection of slides. Both Kline and his wife Eleanor, who could be seen driving him around town since he never learned to drive, were extremely well respected in the larger community during their time in Lubbock. The longest serving rabbi in the congregation’s history, Kline retired from Shaareth Israel in 1980 after 20 years. The congregation grew under Rabbi Kline’s tenure, increasing from 65 member families in 1962 to 96 in 1982.

Lubbock grew into a major city during the post-war years. Between 1940 and 1960, Lubbock’s population increased from 32,000 to 128,000 people. Reese Air Force Base, built during World War II, was an important part of this growth. The Jewish community grew significantly as well, from 60 Jews in 1937 to 212 in 1948. They continued to concentrate in retail trade. Of Shaareth Israel’s 12 board members in 1952, all but two owned retail businesses, primarily clothing stores. Albert Skibell moved to Lubbock after the war and bought Grollman’s clothing store, renaming it Albert’s House of Fashion. His brother Archie opened Skibell’s, another women’s clothing store, in Lubbock after the war. In 1958, the brothers merged their businesses, and built Skibell’s into a small chain that had nine stores across Texas. Albert’s son Charles later ran the business, before closing the last store in 2001.

Shaareth Israel flourished along with the rest of the city. In 1960, the congregation hired Rabbi Alexander Kline from Clarksdale, Mississippi. A native of Hungary, Kline was an art lover and expert, and gave many lectures on art history at the Texas Tech Museum using his personal collection of slides. Both Kline and his wife Eleanor, who could be seen driving him around town since he never learned to drive, were extremely well respected in the larger community during their time in Lubbock. The longest serving rabbi in the congregation’s history, Kline retired from Shaareth Israel in 1980 after 20 years. The congregation grew under Rabbi Kline’s tenure, increasing from 65 member families in 1962 to 96 in 1982.

Shaareth Israel's synagogue, built in 1985

Shaareth Israel's synagogue, built in 1985

The Late 20th Century

Much of the congregation’s growth was due to Texas Tech. By the 1970s, growing numbers of Jewish professors began to teach at Texas Tech as the university began to recruit faculty from outside the Southwest. Henry Shine was among the first Jewish faculty at the school, arriving in the 1950s. Shine spent many years as chairman of the Chemistry Department. Monty Strauss became a Texas Tech math professor in 1971, and later served as Senior Associate Dean of the Graduate School. Jane Winer became a psychology professor in 1975 and spent 17 years as the Dean of Arts & Sciences. In 1970, Texas Tech established its medical and nursing school, which attracted a number of Jews as faculty and administrators. Lubbock also became a regional corporate center, and a growing number of Jewish executives moved to the city. Texas Instruments opened a plant in Lubbock, which attracted about ten Jewish engineers and executives to the city. By the 1980s, the Jewish community was no longer concentrated in the retail business. Of 13 Shaareth Israel board members in 1984, only five owned retail stores. Three were doctors, while four were corporate executives. Over the last few decades, Jewish professionals and academics have largely replaced the Jewish merchants who founded Shaareth Israel.

By 1980, the Jewish community of Lubbock had reached a peak of 350 people. Rabbi Steve Weisberg replaced Rabbi Kline in 1980. Weisberg taught a class in the Biblical Literature Department at Texas Tech until the Texas Attorney General ruled that having clergy teach at the school was unconstitutional. Rabbi Weisberg also reached out to Jews in the small towns of the area and those stationed at Cannon Air Force Base in New Mexico. His tenure was somewhat tumultuous as a disgruntled faction broke away to form another Reform congregation, Beth Shalom. While one of the reasons for the split was dissatisfaction with the rabbi, it was not the only cause since the schism continued even after Rabbi Weisberg left in 1987. In 1989, Beth Shalom reportedly had 25 members and met for services once a month; they would bring in a visiting rabbi for the High Holidays. The Union of American Hebrew Congregations would not recognize the breakaway, and the group eventually disbanded with most members rejoining Shaareth Israel. While there have been other disputes in recent years, Shaareth Israel remains the only Jewish congregation in Lubbock.

Much of the congregation’s growth was due to Texas Tech. By the 1970s, growing numbers of Jewish professors began to teach at Texas Tech as the university began to recruit faculty from outside the Southwest. Henry Shine was among the first Jewish faculty at the school, arriving in the 1950s. Shine spent many years as chairman of the Chemistry Department. Monty Strauss became a Texas Tech math professor in 1971, and later served as Senior Associate Dean of the Graduate School. Jane Winer became a psychology professor in 1975 and spent 17 years as the Dean of Arts & Sciences. In 1970, Texas Tech established its medical and nursing school, which attracted a number of Jews as faculty and administrators. Lubbock also became a regional corporate center, and a growing number of Jewish executives moved to the city. Texas Instruments opened a plant in Lubbock, which attracted about ten Jewish engineers and executives to the city. By the 1980s, the Jewish community was no longer concentrated in the retail business. Of 13 Shaareth Israel board members in 1984, only five owned retail stores. Three were doctors, while four were corporate executives. Over the last few decades, Jewish professionals and academics have largely replaced the Jewish merchants who founded Shaareth Israel.

By 1980, the Jewish community of Lubbock had reached a peak of 350 people. Rabbi Steve Weisberg replaced Rabbi Kline in 1980. Weisberg taught a class in the Biblical Literature Department at Texas Tech until the Texas Attorney General ruled that having clergy teach at the school was unconstitutional. Rabbi Weisberg also reached out to Jews in the small towns of the area and those stationed at Cannon Air Force Base in New Mexico. His tenure was somewhat tumultuous as a disgruntled faction broke away to form another Reform congregation, Beth Shalom. While one of the reasons for the split was dissatisfaction with the rabbi, it was not the only cause since the schism continued even after Rabbi Weisberg left in 1987. In 1989, Beth Shalom reportedly had 25 members and met for services once a month; they would bring in a visiting rabbi for the High Holidays. The Union of American Hebrew Congregations would not recognize the breakaway, and the group eventually disbanded with most members rejoining Shaareth Israel. While there have been other disputes in recent years, Shaareth Israel remains the only Jewish congregation in Lubbock.

By the early 1980s, the congregation began to discuss moving into a new building, though this prospect seemed remote since the congregation was struggling financially. In 1983, Marvin Feldman, the son of original founder Louis Feldman, offered to help pay for a new synagogue for Shaareth Israel. Feldman’s $200,000 donation and land donated by members of the congregation enabled Shaareth Israel to move to a new larger building on the outskirts of the city. Shaareth Israel sold their old synagogue before the new one was completed, meeting at the Second Baptist Church for Shabbat services during the interim. When the new house of worship was dedicated in January, 1985, the building was completely debt-free.

Shaareth Israel went without a rabbi for a few years after Rabbi Weisberg left for Tyler, Texas, in 1987. Member Fred Senatore usually led services during this time. In 1990, the congregation hired Rabbi Sherman Stein, who led Shaareth Israel for six years. Rabbi Heidi Coretz served as spiritual leader from 1997 to 1999. After Rabbi Coretz left, Shaareth Israel brought in students rabbis from Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles for the next seven years. During the 1980s and 90s, the congregation’s membership remained steady at just under 100 member families. In 2006, Rabbi Vicki Hollander became the full-time rabbi at Shaareth Israel.

Community Engagement

The members of Shaareth Israel have long reached out to the larger Lubbock community. In 1969, Shaareth Israel started “Food-o-Rama,” in which the Sisterhood cooked and sold traditional Jewish foods to the larger community. Once a year, Lubbock residents lined up to buy knishes, blintzes, cabbage rolls, and matzah ball soup. Food-o-Rama was a major fundraiser for the congregation until it was discontinued in 1986. For over 40 years, Shaareth Israel has had an annual exchange with Second Baptist Church. Over the course of a weekend, members of Second Baptist attend Friday nights services at Shaareth Israel, while temple members visit the church for Sunday morning services.

Shaareth Israel went without a rabbi for a few years after Rabbi Weisberg left for Tyler, Texas, in 1987. Member Fred Senatore usually led services during this time. In 1990, the congregation hired Rabbi Sherman Stein, who led Shaareth Israel for six years. Rabbi Heidi Coretz served as spiritual leader from 1997 to 1999. After Rabbi Coretz left, Shaareth Israel brought in students rabbis from Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles for the next seven years. During the 1980s and 90s, the congregation’s membership remained steady at just under 100 member families. In 2006, Rabbi Vicki Hollander became the full-time rabbi at Shaareth Israel.

Community Engagement

The members of Shaareth Israel have long reached out to the larger Lubbock community. In 1969, Shaareth Israel started “Food-o-Rama,” in which the Sisterhood cooked and sold traditional Jewish foods to the larger community. Once a year, Lubbock residents lined up to buy knishes, blintzes, cabbage rolls, and matzah ball soup. Food-o-Rama was a major fundraiser for the congregation until it was discontinued in 1986. For over 40 years, Shaareth Israel has had an annual exchange with Second Baptist Church. Over the course of a weekend, members of Second Baptist attend Friday nights services at Shaareth Israel, while temple members visit the church for Sunday morning services.

The Jewish Community in Lubbock Today

In recent years, Lubbock’s Jewish community has started to shrink. By 2001, an estimated 230 Jews lived in the city, down from 350 Jews that had lived there 20 years earlier. The congregation’s membership has dropped from 93 families in 1995 to 62 in 2011. In 2012, Shaareth Israel’s rabbi, Vicki Hollander, became part-time since the congregation could no longer afford a full-time spiritual leader. Most of the congregation’s members are affiliated with Texas Tech or its medical school. One problem with relying on Jewish faculty at Texas Tech is that many choose not to affiliate with a congregation. Despite this, enough faculty do join Shaareth Israel to keep it active and young. The religious school in 2012 had 15 students, with six in the preschool class. While Texas Tech has transformed Shaareth Israel in recent decades, Jewish life on campus remains limited. There is a small but active Hillel chapter, though it does not have its own building. In 2012, there were an estimated 100 Jewish students on campus, far lower than at the other major state universities in Texas. Nevertheless, the presence of the university will ensure the future of Shaareth Israel and the Lubbock Jewish community.