Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Luling, Texas

Luling: Historical Overview

When one drives through Luling, it doesn’t take long to understand the origin of the town. The train tracks which bisect its downtown point to the crucial role of the railroad in the town’s development. Luling was created when the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railroad terminated its line in a rural area not far from Plum Creek in 1874. Developers quickly swooped in, including Thomas Pierce of Boston, Massachusetts, who divided much of the land into lots and sold them to newly arriving settlers, many of whom came from nearby towns like Atlanta, Texas, that had been bypassed by the railroad. Luling quickly became a little boomtown, reaching a population of 2,000 by the end of 1874. Among the earliest settlers of Luling were a handful of Jewish merchants who set up shop along the newly formed streets flanking either side of the train tracks.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Luling

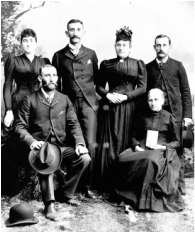

Joseph Josey and family.

Joseph Josey and family. Photo courtesy of the Institute of Texan Cultures

Early Settlers

A list of people who bought Luling’s original lots from Pierce contains several Jews, including Joseph Josey, who was perhaps the first Jew to live in the area. A native of Bavaria, Josey lived in Louisiana before moving to Texas in 1861. By 1870, Josey lived in Lockhart. Four years later, he moved 15 miles south to the burgeoning town of Luling and opened a grocery and hardware store. Polish-born B.J. Kamien and Prussian-native Louis Lichtenstein also bought lots from Pierce in 1874, with both opening retail stores in Luling. Lichtenstein had moved to Luling after living in Illinois. By 1878, there were several Jewish-owned stores in the town, many of which were partnerships, including Epstein & Miller, Nathan & Finkelstein, and Kleinsmith & Jacobs, who advertised that customers could find “everything from an elephant to a pin” at the store. These Jewish-owned stores often advertised themselves as selling more fashionable and cosmopolitan merchandise for lower prices. An 1889 ad for Kleinsmith & Jacobs noted that one of the owners had recently returned from New York “and other trade centers of the East where he purchased a stock of goods that will charm all beholders,” while promising prices that would make their competitors “turn pale with fear and shake with fright.”

A list of people who bought Luling’s original lots from Pierce contains several Jews, including Joseph Josey, who was perhaps the first Jew to live in the area. A native of Bavaria, Josey lived in Louisiana before moving to Texas in 1861. By 1870, Josey lived in Lockhart. Four years later, he moved 15 miles south to the burgeoning town of Luling and opened a grocery and hardware store. Polish-born B.J. Kamien and Prussian-native Louis Lichtenstein also bought lots from Pierce in 1874, with both opening retail stores in Luling. Lichtenstein had moved to Luling after living in Illinois. By 1878, there were several Jewish-owned stores in the town, many of which were partnerships, including Epstein & Miller, Nathan & Finkelstein, and Kleinsmith & Jacobs, who advertised that customers could find “everything from an elephant to a pin” at the store. These Jewish-owned stores often advertised themselves as selling more fashionable and cosmopolitan merchandise for lower prices. An 1889 ad for Kleinsmith & Jacobs noted that one of the owners had recently returned from New York “and other trade centers of the East where he purchased a stock of goods that will charm all beholders,” while promising prices that would make their competitors “turn pale with fear and shake with fright.”

Oscar Walcowich and his family

Oscar Walcowich and his family

Organized Jewish Life in Luling

In 1879, Charles Wessolowsky, a correspondent for the Jewish South newspaper and an organizer for the B’nai B’rith fraternal society, visited Luling and reported that there were ten Jewish families living in the town, which he called “a small place of some importance.” He remarked at how quickly the town and its Jewish community had developed. Indeed, Luling Jews established a Jewish cemetery in 1875; its first burial took place four years later after local peddler William Finkelstein was murdered while on the road. In 1879, Luling Jews founded a Hebrew Benevolent Society that oversaw the cemetery and dispensed charity to Jews in need. The society also held services for the High Holidays of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. In 1878, the local newspaper noted that “the Hebrew merchants of Luling” would close their stores for two days for Rosh Hashanah and would hold services in a building downtown. By 1888, Luling Jews were holding High Holiday services in the local opera house, which attracted numerous Jews from neighboring towns. Luling Jews continued to hold these services as late as 1900. These services were likely Orthodox since they celebrated Rosh Hashanah for the traditional two days, rather than the one day that Reform Jews observed. Nevertheless, these merchants regularly kept their stores open on Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, since that was their biggest day for business.

Jewish Businesses in Luling

By the 1880s, Jews played a prominent role in the local economy. In 1882, Jews owned 14 of Luling’s 69 businesses, or 20%. Three of these retail businesses were run by women, including Rachel Finkelstein and Sarah Marx, who both owned grocery stores, and Sallie Cohn, who ran her family’s general store. Of these 14 businesses, half were grocery stores while four were general dry goods stores.

In 1879, Charles Wessolowsky, a correspondent for the Jewish South newspaper and an organizer for the B’nai B’rith fraternal society, visited Luling and reported that there were ten Jewish families living in the town, which he called “a small place of some importance.” He remarked at how quickly the town and its Jewish community had developed. Indeed, Luling Jews established a Jewish cemetery in 1875; its first burial took place four years later after local peddler William Finkelstein was murdered while on the road. In 1879, Luling Jews founded a Hebrew Benevolent Society that oversaw the cemetery and dispensed charity to Jews in need. The society also held services for the High Holidays of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. In 1878, the local newspaper noted that “the Hebrew merchants of Luling” would close their stores for two days for Rosh Hashanah and would hold services in a building downtown. By 1888, Luling Jews were holding High Holiday services in the local opera house, which attracted numerous Jews from neighboring towns. Luling Jews continued to hold these services as late as 1900. These services were likely Orthodox since they celebrated Rosh Hashanah for the traditional two days, rather than the one day that Reform Jews observed. Nevertheless, these merchants regularly kept their stores open on Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, since that was their biggest day for business.

Jewish Businesses in Luling

By the 1880s, Jews played a prominent role in the local economy. In 1882, Jews owned 14 of Luling’s 69 businesses, or 20%. Three of these retail businesses were run by women, including Rachel Finkelstein and Sarah Marx, who both owned grocery stores, and Sallie Cohn, who ran her family’s general store. Of these 14 businesses, half were grocery stores while four were general dry goods stores.

Life in Luling

The Jewish community in Luling was close-knit, with many kinship ties between its members. According to the 1880 census, 18 Jewish families lived in Luling, consisting of 62 total Jews. Several of them lived on the same street. In 1880 Herman Joseph, Oscar Walcowich and the families of Reuben Jacobs, Abraham Mazur, Louis Lichtenstein, Hyman Kleinsmith, Marks Epstein, and B.J. Kamien all lived on one block. Oscar Walcowich, whose family would remain in Luling well into the 20th century, owned a livery stable and sold livestock. His son, Rube, took over the business and ran it until his death in 1946. Another of Oscar’s sons, Ish Walcowich, owned a dry cleaning and tailor shop.

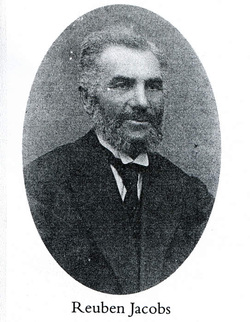

One of the most colorful and prominent members of the Luling Jewish community was Reuben Jacobs, who had left his native Poland in 1867, when he was only 16 years old. After living with a cousin in upstate New York, Jacobs began to peddle his way southward, eventually settling in Atlanta, Texas. When Luling became the railroad terminus in 1874, Jacobs moved to the new town, opening a dry goods store with another Jewish immigrant, Hyman Kleinsmith. Later, Jacobs took over sole control of the store, renaming it R. Jacobs. According to family lore, Reuben once sold goods to the notorious outlaw John Wesley Hardin, who paid him in gold. Jacobs had a reputation as a tough guy, and supposedly the local Ku Klux Klan would avoid marching in front of his store when they paraded in Luling. When Jacobs heard that the Klan was going to target a Catholic friend of his, he let it be known that he would be there with his shotgun to defend him, and the Klan left his friend alone. Once when Reuben got into a fistfight, his opponent tried to pull a knife on him. Reuben’s older brother Gurshia used an ax handle to knock the man down, who hit his head on the curb and died. Although a judge exonerated him, Gurshia still fled the city after the dead man’s family vowed revenge.

The Jewish community in Luling was close-knit, with many kinship ties between its members. According to the 1880 census, 18 Jewish families lived in Luling, consisting of 62 total Jews. Several of them lived on the same street. In 1880 Herman Joseph, Oscar Walcowich and the families of Reuben Jacobs, Abraham Mazur, Louis Lichtenstein, Hyman Kleinsmith, Marks Epstein, and B.J. Kamien all lived on one block. Oscar Walcowich, whose family would remain in Luling well into the 20th century, owned a livery stable and sold livestock. His son, Rube, took over the business and ran it until his death in 1946. Another of Oscar’s sons, Ish Walcowich, owned a dry cleaning and tailor shop.

One of the most colorful and prominent members of the Luling Jewish community was Reuben Jacobs, who had left his native Poland in 1867, when he was only 16 years old. After living with a cousin in upstate New York, Jacobs began to peddle his way southward, eventually settling in Atlanta, Texas. When Luling became the railroad terminus in 1874, Jacobs moved to the new town, opening a dry goods store with another Jewish immigrant, Hyman Kleinsmith. Later, Jacobs took over sole control of the store, renaming it R. Jacobs. According to family lore, Reuben once sold goods to the notorious outlaw John Wesley Hardin, who paid him in gold. Jacobs had a reputation as a tough guy, and supposedly the local Ku Klux Klan would avoid marching in front of his store when they paraded in Luling. When Jacobs heard that the Klan was going to target a Catholic friend of his, he let it be known that he would be there with his shotgun to defend him, and the Klan left his friend alone. Once when Reuben got into a fistfight, his opponent tried to pull a knife on him. Reuben’s older brother Gurshia used an ax handle to knock the man down, who hit his head on the curb and died. Although a judge exonerated him, Gurshia still fled the city after the dead man’s family vowed revenge.

Jacobs experienced tragedy within his own family in 1899. His nephew, Ben Jacobs, fell in love with Reuben’s oldest daughter, Mamie, his first cousin. When she rejected his marriage proposal, Ben shot and killed Mamie in Reuben’s store before killing himself. The local newspaper described the sad incident, concluding that Ben Jacobs “now lies cold in his grave while his remorseless and crime stricken soul is paying the penalty for the terrible vengeance he wreaked upon a family who had been his benefactors.”

Despite these scandalous events, Reuben became a respected and successful local businessman. His department store occupied two buildings in downtown Luling, while he also owned lots of other downtown properties in addition to 22 farms in the area. Reuben’s son, Ben Mark Jacobs, joined his father in the store, which became known as R. Jacobs & Sons. Ben Mark was elected mayor of Luling in the 1930s.

As longtime residents, Reuben Jacobs and Oscar Walcowich were the exceptions among the first wave of Jewish settlers in Luling, most of whom left the town within a few years. B.J. Kamien sold off his store’s merchandise in 1887, closing his business and leaving Luling. Nathan Marx owned a grocery store in 1880, but had left by 1890. By 1890, only six Jewish businesses remained in Luling, down from 14 just eight years earlier. The great expectations for Luling’s growth just after the railroad was built did not pan out, as the town’s population plateaued at 2,000 residents and had even begun to shrink by the turn of the 20th century. The early 1880s would prove to be the apex of Luling’s Jewish community, and for the next century, the Jewish population underwent a long, slow decline.

Despite these scandalous events, Reuben became a respected and successful local businessman. His department store occupied two buildings in downtown Luling, while he also owned lots of other downtown properties in addition to 22 farms in the area. Reuben’s son, Ben Mark Jacobs, joined his father in the store, which became known as R. Jacobs & Sons. Ben Mark was elected mayor of Luling in the 1930s.

As longtime residents, Reuben Jacobs and Oscar Walcowich were the exceptions among the first wave of Jewish settlers in Luling, most of whom left the town within a few years. B.J. Kamien sold off his store’s merchandise in 1887, closing his business and leaving Luling. Nathan Marx owned a grocery store in 1880, but had left by 1890. By 1890, only six Jewish businesses remained in Luling, down from 14 just eight years earlier. The great expectations for Luling’s growth just after the railroad was built did not pan out, as the town’s population plateaued at 2,000 residents and had even begun to shrink by the turn of the 20th century. The early 1880s would prove to be the apex of Luling’s Jewish community, and for the next century, the Jewish population underwent a long, slow decline.

Max & Goldye Finkel

Max & Goldye Finkel

The Community Slowly Declines

By 1900, only eight Jewish families remained in Luling; by 1920, there were only five families, representing 23 total Jews. After oil was discovered in nearby fields, Luling experienced a brief boom in the 1920s, as its population jumped from 1,500 in 1925 to almost 6,000 in 1935. Its Jewish population grew slightly as well, with eight families, most of whom were the children of Luling’s old Jewish residents like Reuben Jacobs and Oscar Walcowich. This boom soon fizzled after the local oil refinery closed in 1939 and moved to Corpus Christi. Luling also lost its standing as a railroad center, as several lines discontinued their routes through the town. By the mid-20th century, only four Jewish families still lived in Luling.

The few Jews who remained struggled to preserve their Jewish traditions. Reuben Jacobs tried to import kosher meat from San Antonio for a while, but it was often spoiled by the time it arrived in Luling. He eventually decided to buy local non-kosher meat. By the early 20th century, Luling Jews no longer held religious services; instead, they would travel to nearby Lockhart for the High Holidays through the 1930s. Some also joined congregations in Austin and San Antonio, though most of the Jewish children raised in Luling during the 1930s and 40s did not receive regular religious instruction.

Max and Goldye Finkel were among the last Jews to live in Luling. Max had left Lithuania in 1909, and spent time in New York City before moving to Texas in the 1910s. In 1917, he opened a small store in Luling, but quickly closed it to join the Army during World War I. While stationed in San Antonio during the war, he married Goldie Walcowich, the daughter of Luling’s Oscar Walcowich. After the war, he opened another store in Luling. According to a feature in the local newspaper published in 1936, “the store grew in prominence and became one of Luling’s better established firms.” Finkel’s department store flourished during Luling’s oil boom. In 1934, Finkel became a founding board member of the First Federal Savings & Loan in Luling Finkel was very involved in civic affairs, supporting many local causes with his time and money.

Finkel was joined in Luling by his older brother Louis and his family. Louis opened the Popular Dry Goods Store, which he ran with his sons Harry and Larry Finkel, who later took over the business on their own, operating it through the 1960s. Max Finkel’s brother-in-law, James Suhler, became a partner in the department store for a time, before opening his own automobile service station during World War II.

Max Finkel was a longtime member of the Conservative congregation Agudas Achim in San Antonio. He was also active in the joint B’nai B’rith lodge that served Luling, Lockhart, Seguin, and Gonzales. During World War II, Finkel led Passover seder for Jewish soldiers stationed at the San Marcos Army Airfield. When he died in 1975, he left money to both Agudas Achim and the Reform congregation Beth El in San Antonio. He also gave money to the National Jewish Hospital in Denver, the Jewish National Fund, and the B’nai B’rith Charity Fund. Finkel’s will reflects the fact that although he lived in a tiny Jewish community that never had a synagogue or formal congregation, he still maintained a strong Jewish identity and supported national Jewish causes.

Finkel continued to run his downtown store until his death, when the business was closed. The closing of Finkel’s, which was the town’s last Jewish-owned business, marked the end of a century of Jewish merchants in Luling. His wife Goldye died three years later in 1978. The building that housed Finkel’s burned down in 2000, but the semi-enclosed lot is now used as an arena for the watermelon seed spitting contest held each year during Luling’s famous Watermelon Thump Festival.

By 1900, only eight Jewish families remained in Luling; by 1920, there were only five families, representing 23 total Jews. After oil was discovered in nearby fields, Luling experienced a brief boom in the 1920s, as its population jumped from 1,500 in 1925 to almost 6,000 in 1935. Its Jewish population grew slightly as well, with eight families, most of whom were the children of Luling’s old Jewish residents like Reuben Jacobs and Oscar Walcowich. This boom soon fizzled after the local oil refinery closed in 1939 and moved to Corpus Christi. Luling also lost its standing as a railroad center, as several lines discontinued their routes through the town. By the mid-20th century, only four Jewish families still lived in Luling.

The few Jews who remained struggled to preserve their Jewish traditions. Reuben Jacobs tried to import kosher meat from San Antonio for a while, but it was often spoiled by the time it arrived in Luling. He eventually decided to buy local non-kosher meat. By the early 20th century, Luling Jews no longer held religious services; instead, they would travel to nearby Lockhart for the High Holidays through the 1930s. Some also joined congregations in Austin and San Antonio, though most of the Jewish children raised in Luling during the 1930s and 40s did not receive regular religious instruction.

Max and Goldye Finkel were among the last Jews to live in Luling. Max had left Lithuania in 1909, and spent time in New York City before moving to Texas in the 1910s. In 1917, he opened a small store in Luling, but quickly closed it to join the Army during World War I. While stationed in San Antonio during the war, he married Goldie Walcowich, the daughter of Luling’s Oscar Walcowich. After the war, he opened another store in Luling. According to a feature in the local newspaper published in 1936, “the store grew in prominence and became one of Luling’s better established firms.” Finkel’s department store flourished during Luling’s oil boom. In 1934, Finkel became a founding board member of the First Federal Savings & Loan in Luling Finkel was very involved in civic affairs, supporting many local causes with his time and money.

Finkel was joined in Luling by his older brother Louis and his family. Louis opened the Popular Dry Goods Store, which he ran with his sons Harry and Larry Finkel, who later took over the business on their own, operating it through the 1960s. Max Finkel’s brother-in-law, James Suhler, became a partner in the department store for a time, before opening his own automobile service station during World War II.

Max Finkel was a longtime member of the Conservative congregation Agudas Achim in San Antonio. He was also active in the joint B’nai B’rith lodge that served Luling, Lockhart, Seguin, and Gonzales. During World War II, Finkel led Passover seder for Jewish soldiers stationed at the San Marcos Army Airfield. When he died in 1975, he left money to both Agudas Achim and the Reform congregation Beth El in San Antonio. He also gave money to the National Jewish Hospital in Denver, the Jewish National Fund, and the B’nai B’rith Charity Fund. Finkel’s will reflects the fact that although he lived in a tiny Jewish community that never had a synagogue or formal congregation, he still maintained a strong Jewish identity and supported national Jewish causes.

Finkel continued to run his downtown store until his death, when the business was closed. The closing of Finkel’s, which was the town’s last Jewish-owned business, marked the end of a century of Jewish merchants in Luling. His wife Goldye died three years later in 1978. The building that housed Finkel’s burned down in 2000, but the semi-enclosed lot is now used as an arena for the watermelon seed spitting contest held each year during Luling’s famous Watermelon Thump Festival.

The Jewish Community in Luling Today

Luling's Jewish cemetery in 2010

Luling's Jewish cemetery in 2010

Today, the small Jewish cemetery north of downtown remains the only vestige of Jewish life in Luling. While Jews were among the earliest settlers in a town that seemed to hold such promise, most soon moved on to other cities and towns that offered greater economic opportunity. The few that remained set down roots and became fixtures in the local community for a large part of the 20th century.