Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Marshall, Texas

Marshall: Historical Overview

Situated near the Louisiana border, Marshall developed as an important center of trade, transport, and communication in East Texas. Officials in Harrison County established one of the earliest mail routes in Texas, while the first telegraph office in Texas appeared in Marshall in 1854. A stagecoach route connected Marshall with points like Austin, El Paso, New Orleans, and San Diego. In 1858, developers laid 20 miles of track near Marshall in order to connect the city to steamboat traffic on the Red River. Marshall in the later half of the 19th century rode a prosperous wave of railroad construction and development, and many moved into the area to take advantage of the economic upturn.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Marshall

Graves of Lion & Emanuel Kahn,

Graves of Lion & Emanuel Kahn, who fought on opposing sides of the Civil War

Early Settlers

Jews were among the first settlers looking to profit from the expanding economy in Marshall. A 1900 edition of Marshall’s local paper reminisced: “when Marshall was in its infancy: when walking two blocks from the public square one would find himself in the woods…there were Jews in Marshall… they did their full part in the pioneer work of laying the foundation for a splendid city.” According to census data, the first Jews in the Marshall area were German immigrants Meyer Dopplemayer and his brother Daniel. Though dry goods were hard to come by in Harrison County during the 1840s because materials had to be shipped by water from New Orleans, the Dopplemayer brothers opened up a confectionery in Jefferson, and later moved their business to Marshall. The Kahn family, including brothers Lionel, Emanuel, and Abraham, moved to Harrison County from Lorraine, Germany, and entered the retail business.The Civil War ruptured the emerging Jewish merchant community, as Jewish merchants joined different sides of the conflict. Daniel Dopplemayer and Emmanuel Kahn fought for the Confederacy, but Lionel Kahn joined the Union forces. The Civil War pitted brother against brother for a time, but after the conflict Lionel rejoined Marshall’s Jewish merchant community.

Marshall’s economic vitality attracted the migration and business ventures of several Jewish families in the 1850s and 1860s. In order to get away from the cold, dry upstate New York weather that aggravated his asthma, Isaac Wolf moved to Marshall from Syracuse in the late 1850s. Wolf worked as a clerk in Marshall and facilitated the migration of numerous relatives and acquaintances to the city. Like many other Southern Jews, Marshall’s early Jewish residents provided economic opportunities to their less established relatives. Mary Dopplemayer, the sister of the Dopplemayer brothers, immigrated to Syracuse in the 1840s, paying for her ticket with the money she had won in a lottery. Mary married Joe Weisman, and the couple moved from Syracuse to Marshall when Daniel Dopplemayer offered to go into business with Mary’s husband. Weisman and Daniel Dopplemayer worked as partners in the store Weisman and Company for 17 years.

Post-Civil War railroad construction heavily influenced Marshall’s Jewish community. In 1871, the Texas and Pacific Railway Company received Congress’ approval to build a railroad from Marshall to the West coast. The projected railroad construction promised an influx of travelers, contractors, and workers into Marshall, and as a result Lionel and Emanuel Kahn established the Great Railroad Supply Store in 1869. The Kahns provided food, clothing, and other dry goods to Marshall’s residents, and signed a contract with the railroad company to provide groceries for dining cars once the railroad was up and running. By the turn of the century, Marshall enjoyed a good deal of economic prosperity, and as a result the Industrial Removal Office selected Marshall as an area to send poor New York City Jews who hoped to find greater job prospects.

Jews were among the first settlers looking to profit from the expanding economy in Marshall. A 1900 edition of Marshall’s local paper reminisced: “when Marshall was in its infancy: when walking two blocks from the public square one would find himself in the woods…there were Jews in Marshall… they did their full part in the pioneer work of laying the foundation for a splendid city.” According to census data, the first Jews in the Marshall area were German immigrants Meyer Dopplemayer and his brother Daniel. Though dry goods were hard to come by in Harrison County during the 1840s because materials had to be shipped by water from New Orleans, the Dopplemayer brothers opened up a confectionery in Jefferson, and later moved their business to Marshall. The Kahn family, including brothers Lionel, Emanuel, and Abraham, moved to Harrison County from Lorraine, Germany, and entered the retail business.The Civil War ruptured the emerging Jewish merchant community, as Jewish merchants joined different sides of the conflict. Daniel Dopplemayer and Emmanuel Kahn fought for the Confederacy, but Lionel Kahn joined the Union forces. The Civil War pitted brother against brother for a time, but after the conflict Lionel rejoined Marshall’s Jewish merchant community.

Marshall’s economic vitality attracted the migration and business ventures of several Jewish families in the 1850s and 1860s. In order to get away from the cold, dry upstate New York weather that aggravated his asthma, Isaac Wolf moved to Marshall from Syracuse in the late 1850s. Wolf worked as a clerk in Marshall and facilitated the migration of numerous relatives and acquaintances to the city. Like many other Southern Jews, Marshall’s early Jewish residents provided economic opportunities to their less established relatives. Mary Dopplemayer, the sister of the Dopplemayer brothers, immigrated to Syracuse in the 1840s, paying for her ticket with the money she had won in a lottery. Mary married Joe Weisman, and the couple moved from Syracuse to Marshall when Daniel Dopplemayer offered to go into business with Mary’s husband. Weisman and Daniel Dopplemayer worked as partners in the store Weisman and Company for 17 years.

Post-Civil War railroad construction heavily influenced Marshall’s Jewish community. In 1871, the Texas and Pacific Railway Company received Congress’ approval to build a railroad from Marshall to the West coast. The projected railroad construction promised an influx of travelers, contractors, and workers into Marshall, and as a result Lionel and Emanuel Kahn established the Great Railroad Supply Store in 1869. The Kahns provided food, clothing, and other dry goods to Marshall’s residents, and signed a contract with the railroad company to provide groceries for dining cars once the railroad was up and running. By the turn of the century, Marshall enjoyed a good deal of economic prosperity, and as a result the Industrial Removal Office selected Marshall as an area to send poor New York City Jews who hoped to find greater job prospects.

Joe Weisman and Company

Joe Weisman and Company

Organized Jewish Life in Marshall

As Jews in Marshall profited from their business ventures, the community also began to develop a rich religious life. Jews in Marshall founded the Hebrew Benevolent Society in 1868, a group that brought together many of the town’s Jewish merchants. Yellow fever in Shreveport, Louisiana, in 1873 brought Rabbi Greenblatt, who was fleeing the outbreak, to Marshall, where he presided over High Holiday celebrations for ten of Marshall’s Jewish families. The Jewish men of Marshall established Reuben Lodge No. 257 of B’nai B’rith in 1876, and in 1877 a Mrs. Goldstein agreed to teach a Sabbath school in both Hebrew and English. Along with Mrs. Goldstein, Jewish women in Marshall helped their community by establishing the Hebrew Ladies’ Aid Society in 1882, an organization that assisted the wider community and poorer Jewish families in East Texas.

As Jews in Marshall profited from their business ventures, the community also began to develop a rich religious life. Jews in Marshall founded the Hebrew Benevolent Society in 1868, a group that brought together many of the town’s Jewish merchants. Yellow fever in Shreveport, Louisiana, in 1873 brought Rabbi Greenblatt, who was fleeing the outbreak, to Marshall, where he presided over High Holiday celebrations for ten of Marshall’s Jewish families. The Jewish men of Marshall established Reuben Lodge No. 257 of B’nai B’rith in 1876, and in 1877 a Mrs. Goldstein agreed to teach a Sabbath school in both Hebrew and English. Along with Mrs. Goldstein, Jewish women in Marshall helped their community by establishing the Hebrew Ladies’ Aid Society in 1882, an organization that assisted the wider community and poorer Jewish families in East Texas.

Home of Isaac and Amelia Hochwald

Home of Isaac and Amelia Hochwald

In 1881, the Benevolent Society bought a plot of land between Speed and Wall Streets to create a Jewish cemetery. The Mays were the first Jews to be buried in the new cemetery. D.R. May and his wife were Bavarian immigrants who worked as merchants in Marshall until they died in the 1873 yellow fever outbreak. The Mays were disinterred from the city’s burial grounds and reburied in the Jewish cemetery once the land was dedicated.

The Jews of Marshall struck a delicate balance between integrating into the community and maintaining their Jewish traditions. In June of 1887, Jews in Marshall officially organized the Moses Montefiore Congregation and elected Daniel Dopplemeyer as its first president. When the congregation decided it had the resources to hire a rabbi, they advertised for a spiritual leader who knew both German and English, though they decided that services would only be in German once every three months. The appointment of bilingual Rabbi Hyman Saft in 1887 and the scarcity of services in German indicate the immigrant community’s movement towards English and integration into the American mainstream. Though Marshall Jews made many efforts to integrate into the larger community, they were unwilling to assimilate totally. In one instance, Rabbi Saft’s daughter, Hattie, who attended a Catholic school, won an award for being the best pupil of the week and received a chain with a cross on it. Hattie’s father made her return the award and explain that Jews do not wear crosses, and Father Grainger gave her a round metal instead.

In 1877, the Marshall Jewish community received one of its most important members from the Jewish Widows and Orphans Association of New Orleans. Having no children of his own, Lionel Kahn decided to adopt Isaac Hochwald, the son of deceased German immigrants. Hochwald moved to Marshall and began to work in Lionel Kahn’s railroad supply store. By 1895, Hochwald was the manager and cashier of the store and wrote in correspondence to the orphanage that he oversaw “quite an extensive business of $150,000 annually.” Hochwald represented a classic “rags to riches” story, becoming one of East Texas’ most successful businessmen despite his humble childhood. Deeply appreciative of the opportunities that Marshall allowed him, Isaac dedicated much of his time and money to better the community. After Lionel Kahn’s death, Hochwald received a large portion of Kahn’s estate and donated it to fund Marshall’s struggling hospital. Hochwald also served as president of the East Texas Council of Boy Scouts, and helped to organize a baseball league in East Texas. Texans called Hochwald the “Father of Organized Baseball in East Texas,” and he received a lifetime pass to all US Major League baseball parks.

The Jews of Marshall struck a delicate balance between integrating into the community and maintaining their Jewish traditions. In June of 1887, Jews in Marshall officially organized the Moses Montefiore Congregation and elected Daniel Dopplemeyer as its first president. When the congregation decided it had the resources to hire a rabbi, they advertised for a spiritual leader who knew both German and English, though they decided that services would only be in German once every three months. The appointment of bilingual Rabbi Hyman Saft in 1887 and the scarcity of services in German indicate the immigrant community’s movement towards English and integration into the American mainstream. Though Marshall Jews made many efforts to integrate into the larger community, they were unwilling to assimilate totally. In one instance, Rabbi Saft’s daughter, Hattie, who attended a Catholic school, won an award for being the best pupil of the week and received a chain with a cross on it. Hattie’s father made her return the award and explain that Jews do not wear crosses, and Father Grainger gave her a round metal instead.

In 1877, the Marshall Jewish community received one of its most important members from the Jewish Widows and Orphans Association of New Orleans. Having no children of his own, Lionel Kahn decided to adopt Isaac Hochwald, the son of deceased German immigrants. Hochwald moved to Marshall and began to work in Lionel Kahn’s railroad supply store. By 1895, Hochwald was the manager and cashier of the store and wrote in correspondence to the orphanage that he oversaw “quite an extensive business of $150,000 annually.” Hochwald represented a classic “rags to riches” story, becoming one of East Texas’ most successful businessmen despite his humble childhood. Deeply appreciative of the opportunities that Marshall allowed him, Isaac dedicated much of his time and money to better the community. After Lionel Kahn’s death, Hochwald received a large portion of Kahn’s estate and donated it to fund Marshall’s struggling hospital. Hochwald also served as president of the East Texas Council of Boy Scouts, and helped to organize a baseball league in East Texas. Texans called Hochwald the “Father of Organized Baseball in East Texas,” and he received a lifetime pass to all US Major League baseball parks.

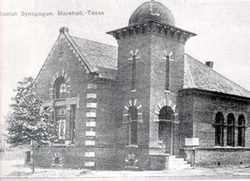

Temple Moses Montefiore

Temple Moses Montefiore

Hochwald also became an important leader for the Jewish community as it continued to grow in Marshall. The Moses Montefiore Congregation elected him president in 1893, a position that he held until 1918. Under Hochwald’s stewardship, the congregation used donations made by members like Lionel Kahn to purchase a lot at the corner of Fulton and Burleson in the autumn of 1894. The Moses Montefiore Fair Association put on several fundraising events to raise the necessary money to build a temple. Marshall’s Christian population was glad to help Marshall’s Jewish residents construct a place of worship; several Christian women served on the Fair Association committee, and the entire Marshall community turned out for the fundraising.

By 1900, the Jewish community had raised enough money and began constructing the temple. The congregation commissioned local architect C.G. Lancaster to design the temple and contracted the firm Sonnefield and Emmons to build it. Builders finished the synagogue in August of 1900, and Marshall’s landscape changed considerably with the addition of the temple’s Middle Eastern architectural style. At the temple dedication ceremony, the oldest congregant opened the Ark, and Christian community members provided vocal music in Hebrew to commemorate the building’s opening.

The synagogue became the center of Jewish life in Marshall throughout the early 20th century. Along with other events sponsored by Jewish charity societies, the congregation staged a masquerade ball in 1909 to raise money for a new organ. By 1925, the congregation had reached a peak of 50 member families. Despite the economic downturn of the Great Depression, the Temple Sisterhood successfully funded the construction of a temple annex in 1939 that included a social hall for congregation meetings, a stage, a kitchen, and a rabbi’s study. The Temple Sisterhood cut up pounds of brisket, chuck roast, tomatoes, and chili peppers to make Mable Stein’s hot tamales and then sold them to help pay for the addition.

By 1900, the Jewish community had raised enough money and began constructing the temple. The congregation commissioned local architect C.G. Lancaster to design the temple and contracted the firm Sonnefield and Emmons to build it. Builders finished the synagogue in August of 1900, and Marshall’s landscape changed considerably with the addition of the temple’s Middle Eastern architectural style. At the temple dedication ceremony, the oldest congregant opened the Ark, and Christian community members provided vocal music in Hebrew to commemorate the building’s opening.

The synagogue became the center of Jewish life in Marshall throughout the early 20th century. Along with other events sponsored by Jewish charity societies, the congregation staged a masquerade ball in 1909 to raise money for a new organ. By 1925, the congregation had reached a peak of 50 member families. Despite the economic downturn of the Great Depression, the Temple Sisterhood successfully funded the construction of a temple annex in 1939 that included a social hall for congregation meetings, a stage, a kitchen, and a rabbi’s study. The Temple Sisterhood cut up pounds of brisket, chuck roast, tomatoes, and chili peppers to make Mable Stein’s hot tamales and then sold them to help pay for the addition.

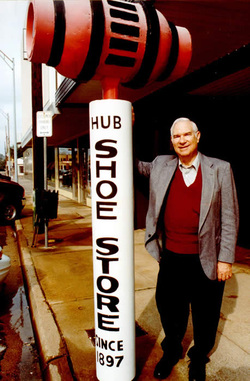

Louis Kariel, Jr. standing outside of the

Louis Kariel, Jr. standing outside of the Hub Shoe Store

The 1930s and 1940s

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, the Jewish community continued to grow and influence the development of Marshall. In 1937, an estimated 130 Jews lived in Marshall. After participating in the Retail Merchants Association and in the American Legion, Louis Kariel was elected mayor of Marshall in 1935, serving in that position until 1947. Kariel and the Jewish community of Marshall offered a place of sanctuary for the Katz family. Adolph Katz and his family fled from Madgeburg, Germany, to escape Nazi persecution prior to the war. Two years after arriving in the US, Adolph moved his family to Marshall and began working in Louis Kariel’s Hub Shoe Store. The Katz family received citizenship in 1943, and continued living in the community that gave them a home. Marshall Jews were active during the war effort. Several served in the armed forces, while the Marshall Sisterhood partook in Red Cross work. The congregation used their temple to host patriotic services for the wider community. In the trying times of economic depression and war, the Jews of Marshall took measures to care for their neighbors.

The Community Declines

Marshall’s congregation was never very large. During the 1930s and 40s, about 43 families belonged to Moses Montefiore. Nevertheless, the small congregation was able to employ rabbinic leadership during this era. Yet the Marshall congregation faced various hardships in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Business and capital moved towards growing cities like Dallas and Houston. As a result, many of the Jews in Marshall moved away to pursue education and business endeavors elsewhere. By 1962, only 15 families belonged to the congregation. Though congregants continued to hold services on Fridays in Marshall, the Jewish community became too small to support a full-time rabbi. The state of the congregation worsened when Valerie Weisman (the wife of Joe Hirsch) died. As Audrey Kariel reminisced, Valerie was the “backbone of the temple, of Sunday school, [and] of the Women’s Society” and her death sapped the congregation’s vitality. The Sisterhood and Ladies’ Aid Society stopped holding regular meetings, and the temple stopped holding Sunday school. Parents began to drive their children to Temple Emanu-El in Longview for Sunday school, a transition that many Jews in Marshall identified as the beginning of their congregation’s demise. The temple remained in the town physically, but the spirit and vitality of the place fell victim to demographics, migration, and old age.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, the Jewish community continued to grow and influence the development of Marshall. In 1937, an estimated 130 Jews lived in Marshall. After participating in the Retail Merchants Association and in the American Legion, Louis Kariel was elected mayor of Marshall in 1935, serving in that position until 1947. Kariel and the Jewish community of Marshall offered a place of sanctuary for the Katz family. Adolph Katz and his family fled from Madgeburg, Germany, to escape Nazi persecution prior to the war. Two years after arriving in the US, Adolph moved his family to Marshall and began working in Louis Kariel’s Hub Shoe Store. The Katz family received citizenship in 1943, and continued living in the community that gave them a home. Marshall Jews were active during the war effort. Several served in the armed forces, while the Marshall Sisterhood partook in Red Cross work. The congregation used their temple to host patriotic services for the wider community. In the trying times of economic depression and war, the Jews of Marshall took measures to care for their neighbors.

The Community Declines

Marshall’s congregation was never very large. During the 1930s and 40s, about 43 families belonged to Moses Montefiore. Nevertheless, the small congregation was able to employ rabbinic leadership during this era. Yet the Marshall congregation faced various hardships in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Business and capital moved towards growing cities like Dallas and Houston. As a result, many of the Jews in Marshall moved away to pursue education and business endeavors elsewhere. By 1962, only 15 families belonged to the congregation. Though congregants continued to hold services on Fridays in Marshall, the Jewish community became too small to support a full-time rabbi. The state of the congregation worsened when Valerie Weisman (the wife of Joe Hirsch) died. As Audrey Kariel reminisced, Valerie was the “backbone of the temple, of Sunday school, [and] of the Women’s Society” and her death sapped the congregation’s vitality. The Sisterhood and Ladies’ Aid Society stopped holding regular meetings, and the temple stopped holding Sunday school. Parents began to drive their children to Temple Emanu-El in Longview for Sunday school, a transition that many Jews in Marshall identified as the beginning of their congregation’s demise. The temple remained in the town physically, but the spirit and vitality of the place fell victim to demographics, migration, and old age.

Audrey Kariel, who served as

Audrey Kariel, who served as mayor of Marshall from 1994 to 2001

Though the congregation dwindled, Jews in Marshall continued in their service to the community. Audrey Kariel, who would later go on to be mayor of Marshall from 1994 to 2001, led several Jewish and Christian women on a campaign to create a public library in Marshall. Kariel also helped establish a Symphony League and various other art programs in Marshall. Louis Kariel, Audrey’s husband, served the community in a different way; Louis actively tried to get liquor stores permitted in “dry” Marshall. However, Jews’ active civil involvement could not spare their congregation. In 1972, the remaining Jewish families in Marshall voted to sell the temple lot to the City of Marshall so that the city could build new police and fire stations. That same year, Joe Hirsh sold Weisman and Company, ending 94 years of single-family ownership. Finally, on May 4, 1973, city officials demolished the temple. The congregation sold the organ, donated the ark and eternal light to the local museum, and gave the collection of sheet music to the University of Texas music department.

The Jewish Community in Marshall Today

Though the temple no longer stands on the corner of Fulton and Burleson, the influence of the Jewish community on the development of Marshall remains apparent in the businesses, stores, and libraries that Marshall Jews helped to build.