Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Odessa/Midland, Texas

Odessa/Midland: Historical Overview

|

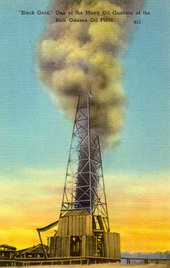

The Permian Basin stretches over 75,000 square miles of west Texas. With land containing a thick deposit of rocks from the Permian geologic period, the region has spent most of its history as an arid no man’s land. But since the 1920s, the area’s unique geological resources have transformed the basin into a center of oil and natural gas production. Over the last century, the fortunes of the Permian Basin, and its two largest cities, Odessa and Midland, have risen and fallen with the price of oil. Tens of thousands of people have been drawn to the flatlands of West Texas in search of fortune, including a handful of Jews who managed to plant a small but vibrant Jewish community in the basin’s rocky soil.

Both Midland and Odessa were created in the wake of the Texas and Pacific Railway’s effort to connect Dallas and El Paso. In 1881, the halfway point between the two cities was named Midway Station; a few years later the name was changed to Midland. Odessa started out in 1881 as a watering stop for the railroad. Initially, both towns were very small, though Midland developed as a regional shipping center for the area’s cattle ranches in the 1890s. By the turn of the century, about 1,000 people lived in Midland, which would not be formally incorporated until 1906. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Odessa and Midland

Early Settlers

It was Midland’s ranching economy that drew the first Jewish family to settle in the area. Henry Halff had established the Quien Sabe Ranch in Midland County with his father Mayer. After Mayer died in 1905, Henry, a native of San Antonio, inherited the family ranches and moved to Midland to oversee them. Halff built a grand mansion along with a downtown office building to house his livestock and real estate businesses. Halff became a leader of the ranching industry, advocating the improvement of livestock bloodlines and owning ranches that extended into four different counties. He was also a major promoter of dry land farming, touting the benefits of irrigation in self-published booklets. To prove his point, Halff turned one of the water tanks on his property into a swimming pool with a pavilion for dances and picnics. He helped to create the farming industry in the area as his real estate company sold parcels of land to prospective farmers. Halff became very rich, and organized a polo team that competed across the country; he even bred his own polo horses. Although he was a major booster for Midland, Halff moved to Mineral Wells in 1923 because of health problems. By 1930, he was living in Dallas, where he died three year later. While Halff was active in the Jewish communities in San Antonio and Dallas, he was not affiliated with any Jewish community in Midland since there were not yet enough Jews in the Permian Basin to establish a congregation or other organization.

It was Midland’s ranching economy that drew the first Jewish family to settle in the area. Henry Halff had established the Quien Sabe Ranch in Midland County with his father Mayer. After Mayer died in 1905, Henry, a native of San Antonio, inherited the family ranches and moved to Midland to oversee them. Halff built a grand mansion along with a downtown office building to house his livestock and real estate businesses. Halff became a leader of the ranching industry, advocating the improvement of livestock bloodlines and owning ranches that extended into four different counties. He was also a major promoter of dry land farming, touting the benefits of irrigation in self-published booklets. To prove his point, Halff turned one of the water tanks on his property into a swimming pool with a pavilion for dances and picnics. He helped to create the farming industry in the area as his real estate company sold parcels of land to prospective farmers. Halff became very rich, and organized a polo team that competed across the country; he even bred his own polo horses. Although he was a major booster for Midland, Halff moved to Mineral Wells in 1923 because of health problems. By 1930, he was living in Dallas, where he died three year later. While Halff was active in the Jewish communities in San Antonio and Dallas, he was not affiliated with any Jewish community in Midland since there were not yet enough Jews in the Permian Basin to establish a congregation or other organization.

Henry Halff

Henry Halff

This would change after oil was discovered in the 1920s. Both Midland and Odessa were transformed by the discovery of the area’s new “cash crop.” Odessa went from a sleepy town of 750 people in 1925 to a burgeoning city of 5000 four years later. Midland experienced similar growth, reaching a population of 5500 in 1930; by 1929, 36 oil companies had offices in the city. With oil money flowing through the Permian Basin, a handful of Jewish merchants were drawn to the area. In 1928, Manuel Sheinberg owned a clothing store in Midland, while William Daiches had a jewelry store. Neither business lasted as both were gone ten years later. A number of Jewish families set up shop in the small towns of the area, often chasing the oil boom from town to town. Places like Wink, Borger, Monahans, and Crane all had Jewish merchants during the 1930s. Nathan Passur owned a bar and grill famous for its hamburgers in Crane during the Great Depression. Later, he opened a liquor store. In Wink, Louis Hight had a clothing store while Pete Schmerman owned a furniture business. Hyman Fair and Ben King both owned jewelry stores in Monahans. Nathan Winkler owned a dry goods store in Fort Stockton, and sent his son Herman to Odessa in 1936 to open a branch of the business.

Despite the arrival of the oil industry, the Permian Basin’s Jewish community was slow to grow initially. In 1937, Midland had only 17 Jews while Odessa had fewer than ten. One factor may have been the boom and bust cycle of the oil business. The price of oil crashed during the Depression and new discoveries in East Texas glutted the market; by 1932 one third of Midland workers were unemployed. Once the oil industry recovered by the late 1930s, the Jewish community began to grow. By 1941, about 20 Jewish families lived in the Permian Basin, when they first started to meet together in rented buildings for religious services. World War II was an important catalyst. Demand for oil skyrocketed while a new army air base in the area further energized the local economy. The area’s Jews met at the air base and organized the Jewish Service Club, which offered worship services and social events for Jewish soldiers stationed there.

Despite the arrival of the oil industry, the Permian Basin’s Jewish community was slow to grow initially. In 1937, Midland had only 17 Jews while Odessa had fewer than ten. One factor may have been the boom and bust cycle of the oil business. The price of oil crashed during the Depression and new discoveries in East Texas glutted the market; by 1932 one third of Midland workers were unemployed. Once the oil industry recovered by the late 1930s, the Jewish community began to grow. By 1941, about 20 Jewish families lived in the Permian Basin, when they first started to meet together in rented buildings for religious services. World War II was an important catalyst. Demand for oil skyrocketed while a new army air base in the area further energized the local economy. The area’s Jews met at the air base and organized the Jewish Service Club, which offered worship services and social events for Jewish soldiers stationed there.

Temple Beth El's first synagogue

Temple Beth El's first synagogue

Organized Jewish Life in Midland and Odessa

After the war, the Jewish community built on this momentum by establishing a formal congregation, called Temple Beth El, in December, 1945. According to its founding constitution, Beth El had three purposes: “propagation of the faith of Israel,” providing Jewish education to both young and old, and the construction of a house of worship. Ben Glast was the first president of the congregation. The group immediately voted to raise money to build a synagogue. They broke ground in March, 1946, and completed the modest building by September. The women of the congregation established a Sisterhood and created a religious school which they oversaw. Although Beth El was based in Odessa, it attracted members from throughout the basin. Nevertheless, the congregation was small, numbering about 25 families in 1947.

After the war, the Jewish community built on this momentum by establishing a formal congregation, called Temple Beth El, in December, 1945. According to its founding constitution, Beth El had three purposes: “propagation of the faith of Israel,” providing Jewish education to both young and old, and the construction of a house of worship. Ben Glast was the first president of the congregation. The group immediately voted to raise money to build a synagogue. They broke ground in March, 1946, and completed the modest building by September. The women of the congregation established a Sisterhood and created a religious school which they oversaw. Although Beth El was based in Odessa, it attracted members from throughout the basin. Nevertheless, the congregation was small, numbering about 25 families in 1947.

Abe Gerson

Abe Gerson

Jewish Businesses in Midland and Odessa

This burgeoning Jewish community was made up of recent arrivals. Of the leaders of Beth El who were listed on the new synagogue’s cornerstone in 1946, none had lived in Odessa or Midland in 1937. Most of Beth El’s members had been drawn to the area during the wartime boom. Ukrainian-born Ben Sadovnick moved to Odessa from Shreveport in 1941. Over the years, Sadovnick opened a wide array of businesses, including several liquor stores, a hotel, a gas station, and a pipe and supply company. When he died in 1960, Sadovnick was the first person buried in the Beth El cemetery, which had been purchased the previous year. Abe Gerson moved to Odessa in 1946 to open a branch of a jewelry business owned by Nathan Donsky of San Angelo. Three years later, Gerson and his wife Leah opened their own jewelry store in Odessa, which they ran for 20 years. Both were active members of Beth El; Leah was the first president of the Sisterhood.

The early members of Beth El were businessmen. A number operated retail stores, like Ben Nedow, who owned a furniture business. Edward Winkler, Nathan’s son, ran the family store in Fort Stockton for many years. Edward became a leader of the Fort Stockton business community, spending 52 years on the board of the First National Bank, which he helped to found. In 1967, Winkler was named the outstanding citizen of Fort Stockton. Winkler continued to run the department store until he sold it in 1995 and retired. Several other members were in the oil field supply business, including Ben Glast and Adolph Frankel. The oil industry would transform both Midland and Odessa into booming cities in the post-war era.

This burgeoning Jewish community was made up of recent arrivals. Of the leaders of Beth El who were listed on the new synagogue’s cornerstone in 1946, none had lived in Odessa or Midland in 1937. Most of Beth El’s members had been drawn to the area during the wartime boom. Ukrainian-born Ben Sadovnick moved to Odessa from Shreveport in 1941. Over the years, Sadovnick opened a wide array of businesses, including several liquor stores, a hotel, a gas station, and a pipe and supply company. When he died in 1960, Sadovnick was the first person buried in the Beth El cemetery, which had been purchased the previous year. Abe Gerson moved to Odessa in 1946 to open a branch of a jewelry business owned by Nathan Donsky of San Angelo. Three years later, Gerson and his wife Leah opened their own jewelry store in Odessa, which they ran for 20 years. Both were active members of Beth El; Leah was the first president of the Sisterhood.

The early members of Beth El were businessmen. A number operated retail stores, like Ben Nedow, who owned a furniture business. Edward Winkler, Nathan’s son, ran the family store in Fort Stockton for many years. Edward became a leader of the Fort Stockton business community, spending 52 years on the board of the First National Bank, which he helped to found. In 1967, Winkler was named the outstanding citizen of Fort Stockton. Winkler continued to run the department store until he sold it in 1995 and retired. Several other members were in the oil field supply business, including Ben Glast and Adolph Frankel. The oil industry would transform both Midland and Odessa into booming cities in the post-war era.

Roy Elsner

Roy Elsner

Jews were involved in other businesses as well. Roy Elsner moved to Odessa in 1947 to take a broadcasting job at a local radio station. After working his way up to manager, Elsner started his own radio station in 1961, the first commercial FM station in West Texas. Elsner ran the successful station until he sold it and retired in 1993. Elsner served two terms as chairman of the Odessa Chamber of Commerce. Max Winkler, Nathan’s brother, opened a restaurant in the small West Texas town of Monahans. Later, he opened a restaurant in Odessa, selling corned beef sandwiches. In the 1950s, he also opened an additional Odessa restaurant that served yet another staple of American Jewish cuisine: Chinese food. Lou and Zelda Hochman started Luigi’s Italian Restaurant in downtown Midland in 1958. The restaurant is still in business today, owned by their children. Lou served as president of the Texas Restaurant Association, and was a big supporter of the arts. After the final performance of each play presented at Midland Community Theater, Hochman hosted a special dinner party for the cast and crew at Luigi’s. Hochman was also the founder of the West Texas Jazz Society.

Beth El's synagogue, built in 1961

Beth El's synagogue, built in 1961

A Growing Community

Midland and Odessa’s population exploded in the 1950s. Midland grew from 21,000 people in 1950 to over 62,000 in 1960, while Odessa went from 29,000 to 80,000 people in the same period as the city became a center for petrochemical production. Not surprisingly, this growth had an impact on Beth El and the Jewish community. By 1952, Beth El was able to hire its first full-time rabbi, Pizer Jacobs, who had received his training at the Reform Hebrew Union College. Rabbi Jacobs did not stay for more than a year or two, and was replaced Rabbi Phillip Weinberg, who was more traditional. Rabbi Weinberg kept kosher and insisted that musical instruments not be part of Shabbat services. In 1957, Beth El voted not to renew his contract, and began to look for a rabbi who would best fit the unique congregation. According to the board minutes at the time, while the congregation preferred Conservative services, they wanted to hire a Reform rabbi since “from a standpoint of living in the area and mixing socially and professionally with the people here, both Jew and Gentile, a man with a Reform background would be more adaptable than any other.”

This effort to hire a new full-time rabbi was sidetracked by the need of the congregation for a new building. After only ten years, Beth El had outgrown its synagogue. By the end of the 1950s, they had 50 member families, twice as many as they had when their building was dedicated in 1946. By 1958, the members were debating whether to enlarge the synagogue or build a new one. After flirting with the idea of adding an adjacent education building, the congregation decided to sell their temple and build a new one on a different site. The temple board decided that they could not afford a full-time rabbi as well as a new synagogue, so they relied on members to lead services while they raised money for the new building. For the High Holidays, they brought in visiting rabbis.

The new synagogue on North Grandview Street was completed in 1961, and dedicated on January 7, 1962. Rabbi Arthur Kahn and Cantor David Silverman of Conservative congregation B’nai Emunah in Tulsa, Oklahoma led the ceremonies.The dedication banquet started with the song “God Bless America” and ended with “Hatikvah,” the Israeli national anthem. The new building could seat 84 in its sanctuary, but could be expanded to accommodate 170 people. Most notably, the new synagogue had seven classrooms to accommodate the growing religious school, which had about 50 students in the 1960s. Essie Elsner ran the Sunday school for almost two decades, beginning in 1959. The congregation continued to serve Jews from throughout the Permian Basin. At the time of the new temple’s dedication, about 20 of Beth El’s member families lived in Odessa, while another 20 lived in Midland. About 10 families lived in small towns like Crane, Fort Stockton, and Hobbs, New Mexico.

Midland and Odessa’s population exploded in the 1950s. Midland grew from 21,000 people in 1950 to over 62,000 in 1960, while Odessa went from 29,000 to 80,000 people in the same period as the city became a center for petrochemical production. Not surprisingly, this growth had an impact on Beth El and the Jewish community. By 1952, Beth El was able to hire its first full-time rabbi, Pizer Jacobs, who had received his training at the Reform Hebrew Union College. Rabbi Jacobs did not stay for more than a year or two, and was replaced Rabbi Phillip Weinberg, who was more traditional. Rabbi Weinberg kept kosher and insisted that musical instruments not be part of Shabbat services. In 1957, Beth El voted not to renew his contract, and began to look for a rabbi who would best fit the unique congregation. According to the board minutes at the time, while the congregation preferred Conservative services, they wanted to hire a Reform rabbi since “from a standpoint of living in the area and mixing socially and professionally with the people here, both Jew and Gentile, a man with a Reform background would be more adaptable than any other.”

This effort to hire a new full-time rabbi was sidetracked by the need of the congregation for a new building. After only ten years, Beth El had outgrown its synagogue. By the end of the 1950s, they had 50 member families, twice as many as they had when their building was dedicated in 1946. By 1958, the members were debating whether to enlarge the synagogue or build a new one. After flirting with the idea of adding an adjacent education building, the congregation decided to sell their temple and build a new one on a different site. The temple board decided that they could not afford a full-time rabbi as well as a new synagogue, so they relied on members to lead services while they raised money for the new building. For the High Holidays, they brought in visiting rabbis.

The new synagogue on North Grandview Street was completed in 1961, and dedicated on January 7, 1962. Rabbi Arthur Kahn and Cantor David Silverman of Conservative congregation B’nai Emunah in Tulsa, Oklahoma led the ceremonies.The dedication banquet started with the song “God Bless America” and ended with “Hatikvah,” the Israeli national anthem. The new building could seat 84 in its sanctuary, but could be expanded to accommodate 170 people. Most notably, the new synagogue had seven classrooms to accommodate the growing religious school, which had about 50 students in the 1960s. Essie Elsner ran the Sunday school for almost two decades, beginning in 1959. The congregation continued to serve Jews from throughout the Permian Basin. At the time of the new temple’s dedication, about 20 of Beth El’s member families lived in Odessa, while another 20 lived in Midland. About 10 families lived in small towns like Crane, Fort Stockton, and Hobbs, New Mexico.

Robert Taubman

Robert Taubman

The Mid-Century

Jews continued to be active in business in the mid-20th century. In Crane, 30 miles from Odessa, Bob and Helen Tobin owned and operated a dry goods store from 1946 until 2000. Max & Izzy Leaman also owned a dry goods store in Crane, though the two families were next door neighbors and close friends. Bob Tobin and Izzy Leaman would go on buying trips together to make sure they didn’t stock the same merchandise. On Christmas Eve, the families would get together to compare how their respective stores had done during the holiday season. Leaman’s Department Store closed in the late 1970s. In Odessa, too, Jews still owned retail stores during the postwar years. Lil Miller opened the Odessa Uniform Shop in 1959, running it for 14 years before she retired. Yet over the time, more and more professionals and people affiliated with the oil industry joined Beth El. Of the eight officers listed on the cornerstone of Beth El’s 1962 synagogue, three were either engineers or executives for local oil companies. Robert Taubman, the president at the time, was Vice President of Buffalo Petroleum. Dr. Sam Fischer was an optometrist. Only one of the officers, Abe Gerson, owned a retail store.

Jews continued to be active in business in the mid-20th century. In Crane, 30 miles from Odessa, Bob and Helen Tobin owned and operated a dry goods store from 1946 until 2000. Max & Izzy Leaman also owned a dry goods store in Crane, though the two families were next door neighbors and close friends. Bob Tobin and Izzy Leaman would go on buying trips together to make sure they didn’t stock the same merchandise. On Christmas Eve, the families would get together to compare how their respective stores had done during the holiday season. Leaman’s Department Store closed in the late 1970s. In Odessa, too, Jews still owned retail stores during the postwar years. Lil Miller opened the Odessa Uniform Shop in 1959, running it for 14 years before she retired. Yet over the time, more and more professionals and people affiliated with the oil industry joined Beth El. Of the eight officers listed on the cornerstone of Beth El’s 1962 synagogue, three were either engineers or executives for local oil companies. Robert Taubman, the president at the time, was Vice President of Buffalo Petroleum. Dr. Sam Fischer was an optometrist. Only one of the officers, Abe Gerson, owned a retail store.

Temple Beth El

Temple Beth El

Beth El in the Second Half of the 20th Century

With its new building, Beth El continued to straddle Reform and Conservative Judaism. Since Beth El was the only congregation in the Permian Basin, it had to accommodate members of various Jewish backgrounds. When they did not have a full-time rabbi in the late 1950s, Beth El contacted both Hebrew Union College and the Jewish Theological Seminary looking for student rabbis for the High Holidays. Usually, they brought in the Reform HUC students. Orthodox Jews found it hard to preserve many traditions in West Texas. Ben Nedow and his family tried to keep kosher when they first moved to the area, but it became too difficult and expensive to get kosher meat. Beth El’s kitchen was dairy-only to preserve the Jewish dietary laws. While services were more Conservative-oriented, the congregation hired both Reform and Conservative rabbis over the years. When the congregation decided to affiliate with a national movement in 1982, it joined both the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations and the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. In 2012, Beth El continued to belong to both the Reform and Conservative movements.

Over the years, Beth El has had various spiritual leaders, including full-time, visiting, and student rabbis. In 1966, they brought in Rabbi Emanuel Kumin from Shreveport for the High Holidays; the following year, Rabbi Kumin was leading services at Beth El about once a month. In 1968, he led the congregation’s confirmation service. The following year, Beth El was able to hire a full-time rabbi, Josef Zeitin, who stayed for seven years before he was replaced by Rabbi Ross London, whose tenure was brief. During the years in which they did not have a full-time rabbi, Rabbi Kumin returned to serve Beth El as its regular visiting rabbi until he retired. In 1982, Beth El hired Akiva Gerstein as their full-time rabbi, though he was gone by 1984. Rabbi Tracy Klirs became Beth El’s first female rabbi in 1986, serving the congregation for the next two years. By the early 1990s, Beth El no longer had a full-time rabbi. Roy Elsner would often conduct funerals while regular services were lay-led. Ziporah Katzman, who had been raised in Israel, would train kids for their b'nei mitzvah. In 1998, Beth El hired Rabbi Sidney Zimelman of Fort Worth to be their regular visiting rabbi. Rabbi Zimelman, who had earlier led Fort Worth’s Conservative congregation Ahavath Sholom, came to Odessa twice a month. He had an apartment in the city and would walk to synagogue on Shabbat.

The Permian Basin Jewish community has benefited greatly from its local B’nai B’rith chapter. Founded in 1963, the local B’nai B’rith was able to secure a bingo permit in the early 1980s. Ever since, the group has run bingo games that raise money to support the local Jewish community. These bingo proceeds have been used to create a camp and college scholarship fund for local Jewish youth. In recent years, bingo money has been used to support Beth El with a fund to help pay for a full-time rabbi.

With its new building, Beth El continued to straddle Reform and Conservative Judaism. Since Beth El was the only congregation in the Permian Basin, it had to accommodate members of various Jewish backgrounds. When they did not have a full-time rabbi in the late 1950s, Beth El contacted both Hebrew Union College and the Jewish Theological Seminary looking for student rabbis for the High Holidays. Usually, they brought in the Reform HUC students. Orthodox Jews found it hard to preserve many traditions in West Texas. Ben Nedow and his family tried to keep kosher when they first moved to the area, but it became too difficult and expensive to get kosher meat. Beth El’s kitchen was dairy-only to preserve the Jewish dietary laws. While services were more Conservative-oriented, the congregation hired both Reform and Conservative rabbis over the years. When the congregation decided to affiliate with a national movement in 1982, it joined both the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations and the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. In 2012, Beth El continued to belong to both the Reform and Conservative movements.

Over the years, Beth El has had various spiritual leaders, including full-time, visiting, and student rabbis. In 1966, they brought in Rabbi Emanuel Kumin from Shreveport for the High Holidays; the following year, Rabbi Kumin was leading services at Beth El about once a month. In 1968, he led the congregation’s confirmation service. The following year, Beth El was able to hire a full-time rabbi, Josef Zeitin, who stayed for seven years before he was replaced by Rabbi Ross London, whose tenure was brief. During the years in which they did not have a full-time rabbi, Rabbi Kumin returned to serve Beth El as its regular visiting rabbi until he retired. In 1982, Beth El hired Akiva Gerstein as their full-time rabbi, though he was gone by 1984. Rabbi Tracy Klirs became Beth El’s first female rabbi in 1986, serving the congregation for the next two years. By the early 1990s, Beth El no longer had a full-time rabbi. Roy Elsner would often conduct funerals while regular services were lay-led. Ziporah Katzman, who had been raised in Israel, would train kids for their b'nei mitzvah. In 1998, Beth El hired Rabbi Sidney Zimelman of Fort Worth to be their regular visiting rabbi. Rabbi Zimelman, who had earlier led Fort Worth’s Conservative congregation Ahavath Sholom, came to Odessa twice a month. He had an apartment in the city and would walk to synagogue on Shabbat.

The Permian Basin Jewish community has benefited greatly from its local B’nai B’rith chapter. Founded in 1963, the local B’nai B’rith was able to secure a bingo permit in the early 1980s. Ever since, the group has run bingo games that raise money to support the local Jewish community. These bingo proceeds have been used to create a camp and college scholarship fund for local Jewish youth. In recent years, bingo money has been used to support Beth El with a fund to help pay for a full-time rabbi.

Anti-Semitism and Interfaith Activities

Living in an extremely Christian environment has sometimes been a challenge for the members of Beth El. On two occasions in recent decades, vandals have defaced the synagogue. Once, they broke into the building and spray painted “Jesus is coming, be prepared” on a Ten Commandments tablet in the sanctuary. Since the graffiti could not be cleaned off without damaging the tablet, the congregation decided to carve the first letter of each commandment into the reverse side of the tablet and display it.

Faced with such intolerance, members of Beth El have worked to educate their Gentile neighbors. Roy Elsner spoke to many church groups in the area about Judaism. In the 1970s, the congregation started holding the annual Brotherhood Dinner. Members of the Sisterhood would cook traditional Jewish foods such as cabbage rolls, noodle kugel, and tsimmes, and serve them to the larger Odessa community. For many years, Essie Elsner chaired the dinner, which taught local Christians about Jewish culture while raising money for the Sisterhood. Beth El continued to host the Brotherhood Dinner until the late 2000s.

Living in an extremely Christian environment has sometimes been a challenge for the members of Beth El. On two occasions in recent decades, vandals have defaced the synagogue. Once, they broke into the building and spray painted “Jesus is coming, be prepared” on a Ten Commandments tablet in the sanctuary. Since the graffiti could not be cleaned off without damaging the tablet, the congregation decided to carve the first letter of each commandment into the reverse side of the tablet and display it.

Faced with such intolerance, members of Beth El have worked to educate their Gentile neighbors. Roy Elsner spoke to many church groups in the area about Judaism. In the 1970s, the congregation started holding the annual Brotherhood Dinner. Members of the Sisterhood would cook traditional Jewish foods such as cabbage rolls, noodle kugel, and tsimmes, and serve them to the larger Odessa community. For many years, Essie Elsner chaired the dinner, which taught local Christians about Jewish culture while raising money for the Sisterhood. Beth El continued to host the Brotherhood Dinner until the late 2000s.

The Jewish Community in Odessa/Midland Today

While their numbers have shrunk a bit in the last few decades, Beth El and the Permian Basin Jewish community remain strong and vibrant. In 2000, about 200 Jews lived in the Permian Basin. Beth El had 80 member families in 1990, though this figure had dropped to around 65 families in 2012. Beth El still has a religious school, which had 13 students in 2012. Members still live in the small towns of the basin as well as the cities of Midland and Odessa. The congregation still has its feet in both the Reform and Conservative movements. They use the Reform prayer book on Friday nights, and the Conservative prayer book on Saturday mornings. Rabbi Zimelman officially retired in 2011, and Beth El hired Reform Rabbi Holly Cohn to serve as the congregation’s full-time spiritual leader.