Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Orange, Texas

Orange: Historical Overview

Located just across the Sabine River from Louisiana, Orange, Texas, is sometimes known as the “Gateway City.” Named the seat of Orange County in 1852, the town rose to prominence due to the woodlands surrounding the area. By the turn of the 20th century, Orange had become a regional center of the timber industry, as railroads built multiple lines into the small city of 3,800 people to ship the lumber produced in the town’s sawmills. The oil boom in neighboring Jefferson County spilled over into Orange as well in the early 20th century. As Orange developed economically, a growing number of Jews were drawn to the area.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Orange

Orange Jewish cemetery

Orange Jewish cemetery

Early Settlers

One of the earliest Jews in southeast Texas was Simon Wiess. Although he had little connection to organized Judaism during his time in Texas, Wiess was raised in a traditional Jewish home in Poland. Wiess left Poland in 1816. After traveling around the globe, Wiess settled in Texas in 1836, becoming deputy collector of customs for the nascent republic. He soon settled in Nacogdoches where he became a cotton merchant and broker, shipping the cash crop down the Sabine River. In 1840, he moved to Jasper County, just north of Orange County in southeast Texas, setting up business in a river port town that was later named Wiess’ Bluff. Wiess owned steamboats that carried cotton and lumber to downriver ports, and amassed a net worth of $30,000 by 1860. Wiess’ early presence in the region did not result in a permanent Jewish community since he married a Presbyterian woman and raised his children as Christians.

Among the first Jews to live in Orange was James Solinsky, a German-born merchant who settled in town in 1876. Over the next few decades, Jews began settling in Orange in greater numbers. In 1896, a large group of Orange Jews visited Beaumont’s Temple Emanu-El for the Reform congregation’s confirmation ceremony. Although the Galveston newspaper referred to the group as “the Jewish congregation, Orange,” they had yet to formally establish a religious organization.

Included in this early group of Jews were the German-born Julius and Leopold Miller, who had moved to Texas from Louisiana with their families in the late 19th century. Like most of the other Jews in Orange, the Millers were merchants. Not all of these early residents were immigrants. Harry Crager was born in New York, and moved to Orange by 1895, where he opened Crager’s Dry Goods Store. After Crager died tragically in 1904, his widow Freda, a Louisiana native, continued to run the store. Joseph Lucas, who was born in Louisiana, owned a jewelry store in Orange by 1900.

One of the earliest Jews in southeast Texas was Simon Wiess. Although he had little connection to organized Judaism during his time in Texas, Wiess was raised in a traditional Jewish home in Poland. Wiess left Poland in 1816. After traveling around the globe, Wiess settled in Texas in 1836, becoming deputy collector of customs for the nascent republic. He soon settled in Nacogdoches where he became a cotton merchant and broker, shipping the cash crop down the Sabine River. In 1840, he moved to Jasper County, just north of Orange County in southeast Texas, setting up business in a river port town that was later named Wiess’ Bluff. Wiess owned steamboats that carried cotton and lumber to downriver ports, and amassed a net worth of $30,000 by 1860. Wiess’ early presence in the region did not result in a permanent Jewish community since he married a Presbyterian woman and raised his children as Christians.

Among the first Jews to live in Orange was James Solinsky, a German-born merchant who settled in town in 1876. Over the next few decades, Jews began settling in Orange in greater numbers. In 1896, a large group of Orange Jews visited Beaumont’s Temple Emanu-El for the Reform congregation’s confirmation ceremony. Although the Galveston newspaper referred to the group as “the Jewish congregation, Orange,” they had yet to formally establish a religious organization.

Included in this early group of Jews were the German-born Julius and Leopold Miller, who had moved to Texas from Louisiana with their families in the late 19th century. Like most of the other Jews in Orange, the Millers were merchants. Not all of these early residents were immigrants. Harry Crager was born in New York, and moved to Orange by 1895, where he opened Crager’s Dry Goods Store. After Crager died tragically in 1904, his widow Freda, a Louisiana native, continued to run the store. Joseph Lucas, who was born in Louisiana, owned a jewelry store in Orange by 1900.

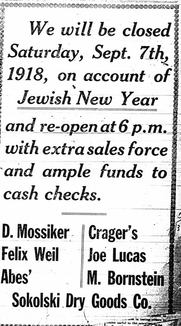

Jewish owned stores advertised their

Jewish owned stores advertised their closing for Rosh Hashanah in 1918

Organized Jewish Life in Orange

By the early 20th century, Jews in Orange began to organize religious institutions. Women led the way, establishing the Ladies Aid and Cemetery Association in 1904. By 1907, the group had ten members and had purchased land for a Jewish cemetery. In 1907, Mrs. Leopold Miller was the association’s president while Anne Lucas was its secretary and treasurer. At the time, 53 Jews lived in Orange. By 1909, they had established a congregation, Beth El, which met at the local Masonic Temple. The group would bring in visiting rabbis, including Rabbi Heiman Elkin from Beaumont and Rabbi Herman Rosenwasser of Lake Charles and later Baton Rouge.

In 1909, the Houston-based Jewish Herald newspaper reported that “the Orthodox congregation” was growing steadily and hoped to build a permanent synagogue. It’s unlikely that the group was strictly Orthodox since they brought in visiting Reform rabbis once a month to lead services and many of its members were either native born or from Germany, where Reform Judaism was predominant. By 1919, the small congregation, numbering 16 members, only met once a month. When Rabbi Samuel Rosinger of Beaumont made his monthly visit, the group would meet at the home of Joe Lucas. The services were in English, an indication that even if the congregation had been originally Orthodox, it quickly adopted Reform practices. Nevertheless, Orange Jews closed their stores for the Jewish High Holidays, if not for the weekly Sabbath. The local newspaper noted in 1918 that “practically all Jewish merchants of Orange will close their various places of business Saturday in observance of the Jewish New Year.”

By the early 20th century, Jews in Orange began to organize religious institutions. Women led the way, establishing the Ladies Aid and Cemetery Association in 1904. By 1907, the group had ten members and had purchased land for a Jewish cemetery. In 1907, Mrs. Leopold Miller was the association’s president while Anne Lucas was its secretary and treasurer. At the time, 53 Jews lived in Orange. By 1909, they had established a congregation, Beth El, which met at the local Masonic Temple. The group would bring in visiting rabbis, including Rabbi Heiman Elkin from Beaumont and Rabbi Herman Rosenwasser of Lake Charles and later Baton Rouge.

In 1909, the Houston-based Jewish Herald newspaper reported that “the Orthodox congregation” was growing steadily and hoped to build a permanent synagogue. It’s unlikely that the group was strictly Orthodox since they brought in visiting Reform rabbis once a month to lead services and many of its members were either native born or from Germany, where Reform Judaism was predominant. By 1919, the small congregation, numbering 16 members, only met once a month. When Rabbi Samuel Rosinger of Beaumont made his monthly visit, the group would meet at the home of Joe Lucas. The services were in English, an indication that even if the congregation had been originally Orthodox, it quickly adopted Reform practices. Nevertheless, Orange Jews closed their stores for the Jewish High Holidays, if not for the weekly Sabbath. The local newspaper noted in 1918 that “practically all Jewish merchants of Orange will close their various places of business Saturday in observance of the Jewish New Year.”

Max Goldfine in his store.

Max Goldfine in his store. Photo courtesy of Heritage House Museum

World War I

The Jewish community flourished during World War I as Orange bustled with wartime production. Due to its abundant supply of lumber and its deep water port, Orange became a shipbuilding center. By the start of 1918, Orange had five active shipyards, which made wooden steamers. The city swelled, practically doubling in size to an estimated 17,000 people during the war. The Jewish community reached its peak during this period, with 69 Jews in 1919. Jewish-owned stores that catered to this growing population included D. Mossiker, Felix Weil, Crager’s, Joe Lucas, Sokolski Dry Goods, and M.B. Aronson Grocery. Yet this wartime boom went bust rather quickly. When the war was over, ship contracts were canceled and half finished ship hulls were taken to the Sabine River and set on fire. Due to this drop in shipbuilding, the town’s population plummeted, settling back down to just over 9,000 people in 1920. Orange was further hurt economically in the 1920s when the local lumber business dried up as the timber industry moved deeper into East Texas. By 1937, only 28 Jews still lived in Orange.

The Jewish community flourished during World War I as Orange bustled with wartime production. Due to its abundant supply of lumber and its deep water port, Orange became a shipbuilding center. By the start of 1918, Orange had five active shipyards, which made wooden steamers. The city swelled, practically doubling in size to an estimated 17,000 people during the war. The Jewish community reached its peak during this period, with 69 Jews in 1919. Jewish-owned stores that catered to this growing population included D. Mossiker, Felix Weil, Crager’s, Joe Lucas, Sokolski Dry Goods, and M.B. Aronson Grocery. Yet this wartime boom went bust rather quickly. When the war was over, ship contracts were canceled and half finished ship hulls were taken to the Sabine River and set on fire. Due to this drop in shipbuilding, the town’s population plummeted, settling back down to just over 9,000 people in 1920. Orange was further hurt economically in the 1920s when the local lumber business dried up as the timber industry moved deeper into East Texas. By 1937, only 28 Jews still lived in Orange.

Jewish Businesses in Orange

Those Jews who remained in Orange continued to concentrate in retail trade. M.B. Aronson, who had left Russia in 1890, opened his grocery store in Orange in 1894. He was soon joined by his brother Goodman. The Aronson Grocery store remained a family business as it grew into a small East Texas chain. M.B.’s brother Joe bought out his stake in the business in 1918 and ran the company for the next 20 years. In 1939, hurt by the effects of the Depression and Orange’s economic decline, Joe Aronson sold the operation and left the city, ending 45 years of business in Orange. Max Goldfine came to the United States from Russia in 1907. In 1928, he opened Goldfine’s, one of Orange’s leading department stores. Not all Orange Jews were merchants. Dr. H.J. Kaplan became Orange’s first ear, nose, and throat specialist when he moved to the city in 1939.

Those Jews who remained in Orange continued to concentrate in retail trade. M.B. Aronson, who had left Russia in 1890, opened his grocery store in Orange in 1894. He was soon joined by his brother Goodman. The Aronson Grocery store remained a family business as it grew into a small East Texas chain. M.B.’s brother Joe bought out his stake in the business in 1918 and ran the company for the next 20 years. In 1939, hurt by the effects of the Depression and Orange’s economic decline, Joe Aronson sold the operation and left the city, ending 45 years of business in Orange. Max Goldfine came to the United States from Russia in 1907. In 1928, he opened Goldfine’s, one of Orange’s leading department stores. Not all Orange Jews were merchants. Dr. H.J. Kaplan became Orange’s first ear, nose, and throat specialist when he moved to the city in 1939.

Abe Sokolski

Abe Sokolski

Civic Engagement

Although they were small in number, Orange Jews were very active in the town’s civic affairs. Harry Crager served as a city commissioner from 1903 until his death a year later. Beginning in 1906, Joe Lucas gave gold medals to Orange High School’s valedictorian and salutatorian each year. Lucas, who owned a jewelry store, was still awarding the medals as late as 1940. Felix Weil served as chairman of the Orange Democratic Executive Committee in 1940, at a time when the Democratic Party was all powerful in Texas. The most politically active Orange Jew was Abe Sokolski, who moved to Orange from Evansville, Indiana, with his parents when he was a boy in the 1890s. Once he was older, Sokolski opened Abe’s, a clothing store in downtown Orange. In 1934, Sokolski began a six-year stint as a city commissioner, during which he oversaw a major road paving and sidewalk project. Based on this record, Sokolski ran for mayor in 1940, although he didn’t do much public campaigning. The local newspaper noted that Sokolski spoke for only about a minute during a candidate forum, stressing his success in the street paving effort and other city improvement projects. While Sokolski was often attacked by his opponents during the campaign, trying to link him to the status quo of the current city administration, they did not raise the issue of his religion. Despite these attacks, Sokolski won easily, receiving more votes than his three opponents combined in the Democratic Primary. Sokolski ran unopposed in the general election.

Once in office, Sokolski moved quickly to fulfill his campaign pledge to run the city “on a progressive economical basis,” cutting the city budget by over 10% and his own salary from $500 to $200 a month. In 1942, he was reelected. Two years later, he convinced a young lawyer in town, Homer Stephenson, to run for mayor, and using his influence, helped get him elected even though Stephenson had only lived in Orange since 1941. Not only was Sokolski’s Jewishness not a hindrance to his political career, for some Orange residents it was a point of pride. One prominent citizen wrote a letter to the local newspaper soon after Sokolski’s election in 1940, proclaiming, “what is your answer to Hitler? Our Mayor-elect, the honorable Abe Sokolski! Our Abe!” To this Orange voter, electing a Jewish man highlighted America’s freedom in contrast to the anti-Semitism of Nazi Germany.

Although they were small in number, Orange Jews were very active in the town’s civic affairs. Harry Crager served as a city commissioner from 1903 until his death a year later. Beginning in 1906, Joe Lucas gave gold medals to Orange High School’s valedictorian and salutatorian each year. Lucas, who owned a jewelry store, was still awarding the medals as late as 1940. Felix Weil served as chairman of the Orange Democratic Executive Committee in 1940, at a time when the Democratic Party was all powerful in Texas. The most politically active Orange Jew was Abe Sokolski, who moved to Orange from Evansville, Indiana, with his parents when he was a boy in the 1890s. Once he was older, Sokolski opened Abe’s, a clothing store in downtown Orange. In 1934, Sokolski began a six-year stint as a city commissioner, during which he oversaw a major road paving and sidewalk project. Based on this record, Sokolski ran for mayor in 1940, although he didn’t do much public campaigning. The local newspaper noted that Sokolski spoke for only about a minute during a candidate forum, stressing his success in the street paving effort and other city improvement projects. While Sokolski was often attacked by his opponents during the campaign, trying to link him to the status quo of the current city administration, they did not raise the issue of his religion. Despite these attacks, Sokolski won easily, receiving more votes than his three opponents combined in the Democratic Primary. Sokolski ran unopposed in the general election.

Once in office, Sokolski moved quickly to fulfill his campaign pledge to run the city “on a progressive economical basis,” cutting the city budget by over 10% and his own salary from $500 to $200 a month. In 1942, he was reelected. Two years later, he convinced a young lawyer in town, Homer Stephenson, to run for mayor, and using his influence, helped get him elected even though Stephenson had only lived in Orange since 1941. Not only was Sokolski’s Jewishness not a hindrance to his political career, for some Orange residents it was a point of pride. One prominent citizen wrote a letter to the local newspaper soon after Sokolski’s election in 1940, proclaiming, “what is your answer to Hitler? Our Mayor-elect, the honorable Abe Sokolski! Our Abe!” To this Orange voter, electing a Jewish man highlighted America’s freedom in contrast to the anti-Semitism of Nazi Germany.

World War II and After

Sokolski was mayor during a time of tremendous flux, as war production once again sent Orange’s shipyards into overdrive. According to one estimate, the town, which had only 7,472 people in 1940, reached a peak of 60,000 during World War II. Orange’s Jewish merchants benefited from this boom, although the economy once again declined after the end of the war. This time, the new petrochemical industry helped to buffer the fall, and 21,000 people remained in Orange in 1950; the city’s population has remained around this level ever since.

Orange’s Jewish community did not develop along with the rest of the city. Being so close to other Jewish congregations in Beaumont and Port Arthur, Orange’s congregation soon dissolved once improved roads and bridges made travel to these other cities relatively easy. Some families joined the Port Arthur congregation, while others would drive to Beaumont for services. While there were still a handful of Jewish-owned stores in Orange during World War II, their numbers gradually shrunk during the next few decades. Max Goldfine opened a shoe store soon after the war, which remained in business until he died in the 1970s. The Spector family owned a newsstand as well as a junk business, while the Grossmans owned a jewelry store. No more than ten Jewish families lived in Orange during the post-war period.

Sokolski was mayor during a time of tremendous flux, as war production once again sent Orange’s shipyards into overdrive. According to one estimate, the town, which had only 7,472 people in 1940, reached a peak of 60,000 during World War II. Orange’s Jewish merchants benefited from this boom, although the economy once again declined after the end of the war. This time, the new petrochemical industry helped to buffer the fall, and 21,000 people remained in Orange in 1950; the city’s population has remained around this level ever since.

Orange’s Jewish community did not develop along with the rest of the city. Being so close to other Jewish congregations in Beaumont and Port Arthur, Orange’s congregation soon dissolved once improved roads and bridges made travel to these other cities relatively easy. Some families joined the Port Arthur congregation, while others would drive to Beaumont for services. While there were still a handful of Jewish-owned stores in Orange during World War II, their numbers gradually shrunk during the next few decades. Max Goldfine opened a shoe store soon after the war, which remained in business until he died in the 1970s. The Spector family owned a newsstand as well as a junk business, while the Grossmans owned a jewelry store. No more than ten Jewish families lived in Orange during the post-war period.

The Jewish Community in Orange Today

Today, there is no Jewish community to speak of in Orange. By the 1960s, virtually none of the early Jewish families still lived in the city. During the next few decades, the community further shrank. By 2010, only one Jew remained in Orange.