Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Palestine, Texas

Palestine: Historical Overview

A statute in the formation of Anderson County, Texas, in the late 1840s, stipulated that the county seat be located in the geographic center of the newly formed county. Palestine, named for a town in Illinois, was formed to serve as the seat for the newly formed county. The town grew slowly at first, but the pace of development quickened significantly with the arrival of the railroad in the early 1870s. However, even prior to the railroad’s arrival, a small group of Jews had built businesses in town and made Palestine their home. As the city grew and prospered in the late 19th century thanks to the railroad, the number of Jews in town swelled and a place of worship, Temple Beth Israel, was constructed at the turn of the century. However, by the 1930s, the Jewish population of Palestine began to fade and Beth Israel was closed in 1940. No Jews remain in Palestine today.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Palestine

Sol Maier

Sol Maier

Early Settlers

In the mid-19th century, Palestine was a small town of about 200 residents with only a few businesses. In 1866, following 20 years of growth following the city’s formation, the populace voted to expand Palestine’s borders and incorporate as a city. Some Jews, almost all of them immigrants to the United States, had arrived in Palestine in the years prior to the town’s incorporation. Among the first Jews to settle permanently in Palestine was Phillip Unger, a Hungarian immigrant, who according to legend, arrived in town with his belongings tied in a red bandana. He became a peddler in the 1850s, opened a general store by 1866, and later became a farmer and a gardener.

Unger was known for his charity, helping new residents of Palestine establish themselves in the city. Among those who received his assistance was Michael Ash, a German immigrant, who, in the mid-1850s, arrived in Palestine and found work as a clerk. Ash later became a successful banker and dry goods merchant and was instrumental in helping to organize Palestine’s Jewish community. Another Prussian immigrant, Edward Teah, who later went into business with Ash, arrived in Palestine by 1858. Michael Ash’s brother, Henry, first arrived in Palestine in 1850, but moved away, returning in 1868. He became a prosperous dry goods merchant and, by the turn of the century, a banker, serving on the board of the First National Bank of Palestine.

By 1880, Jewish immigrants were playing a prominent role in Palestine’s commercial economy. Several owned dry goods stores, including I. Epstein, Charles Jacobs, Adolph Kohn, and Abraham Teah. Some Jews found work as clerks, often in stores owned by other Jews. For example, Michael Ash’s brother Gabriel worked as a cashier in his store, while Lewis Kopf clerked in Charles Jacobs’ store. Often, these clerks later became successful businessmen themselves. Sam Lucas started out working as a clerk in his uncle Charles Jacobs' store, but later became a prominent merchant and cotton buyer. Other Jewish businessmen in town included Lucas’ business partner A.S. Fox, B. Oberstein, who was an auctioneer, and grocer Henry Nathan. Sol Maier, who arrived in Palestine in 1882, got his start as a saloon keeper but later became president of the Palestine Salt and Coal Company as well as the Mechanic’s Building and Loan Company.

In the mid-19th century, Palestine was a small town of about 200 residents with only a few businesses. In 1866, following 20 years of growth following the city’s formation, the populace voted to expand Palestine’s borders and incorporate as a city. Some Jews, almost all of them immigrants to the United States, had arrived in Palestine in the years prior to the town’s incorporation. Among the first Jews to settle permanently in Palestine was Phillip Unger, a Hungarian immigrant, who according to legend, arrived in town with his belongings tied in a red bandana. He became a peddler in the 1850s, opened a general store by 1866, and later became a farmer and a gardener.

Unger was known for his charity, helping new residents of Palestine establish themselves in the city. Among those who received his assistance was Michael Ash, a German immigrant, who, in the mid-1850s, arrived in Palestine and found work as a clerk. Ash later became a successful banker and dry goods merchant and was instrumental in helping to organize Palestine’s Jewish community. Another Prussian immigrant, Edward Teah, who later went into business with Ash, arrived in Palestine by 1858. Michael Ash’s brother, Henry, first arrived in Palestine in 1850, but moved away, returning in 1868. He became a prosperous dry goods merchant and, by the turn of the century, a banker, serving on the board of the First National Bank of Palestine.

By 1880, Jewish immigrants were playing a prominent role in Palestine’s commercial economy. Several owned dry goods stores, including I. Epstein, Charles Jacobs, Adolph Kohn, and Abraham Teah. Some Jews found work as clerks, often in stores owned by other Jews. For example, Michael Ash’s brother Gabriel worked as a cashier in his store, while Lewis Kopf clerked in Charles Jacobs’ store. Often, these clerks later became successful businessmen themselves. Sam Lucas started out working as a clerk in his uncle Charles Jacobs' store, but later became a prominent merchant and cotton buyer. Other Jewish businessmen in town included Lucas’ business partner A.S. Fox, B. Oberstein, who was an auctioneer, and grocer Henry Nathan. Sol Maier, who arrived in Palestine in 1882, got his start as a saloon keeper but later became president of the Palestine Salt and Coal Company as well as the Mechanic’s Building and Loan Company.

Palestine Jewish cemetery

Palestine Jewish cemetery

Organized Jewish Life in Palestine

Upon visiting Palestine in 1879, newspaper editor Charles Wessolowsky noted the zeal with which Jewish residents “engaged in business.” Wessolowsky, too, noted that the Jews of Palestine, satisfied and happy in their current environment, omitted the traditional recitation of the line “next year in Jerusalem” from the Passover Haggadah. However, Wessolowsky bemoaned the fact that, despite the presence of 11 Jewish families and 100 total Jews, no Jewish organizations existed. Perhaps due to his expression of concern, that fact soon changed.

In the early 1880s, the Jews of Palestine finally began organizing themselves formally. An 1882 newspaper article noted that High Holiday services were held in the Masonic Temple with a sermon delivered by Manuel Winner. Winner, a German immigrant, was a jeweler and watchmaker by trade. For many years, though referred to as “rabbi” or “reverend” by newspapers, Winner served the Jews of Palestine as lay leader. Winner performed weddings as well as High Holiday services, including those in 1885 held at Library Hall. Sometime prior to 1883, local Jews founded the Palestine Hebrew Association. In April, 1883, Michael Ash purchased an acre of land and deeded it, alongside part of another tract, to the association. This land became the Jewish cemetery and, upon Ash’s death in May, 1883, his will bequeathed funds for the continued upkeep of the burial ground in which he was laid to rest. Jewish communities in other towns utilized the cemetery as well and individuals from Bryan, Crockett, Henderson, Oakwoods, and Tyler are buried there. Henderson native Charles L. Brachfield, a former state senator and district and county judge, was buried in the Palestine Jewish cemetery.

Leaders in the Community

In addition to creating Jewish institutions, the Jews of Palestine were also taking part in the development of the city itself. Palestine’s growth in the late 19th century can be attributed mainly to the railroad’s arrival in the early 1870s. By the 1880s and 1890s, crops were being shipped out of Palestine as new businesses began to spring up around the railroad tracks. By the 1890s, Palestine’s population reached 9,000 people. In 1879, Wessolosky noted the role the Jews of Palestine were playing in the “building up” of the city. Similarly, Henry Ash’s 1903 obituary claimed that “Mr. Ash has always been identified with the progress and uplifting of Palestine and was one of the leading spirits in promoting its growth.” Phil Myers, a partner in the Grand Leader Department Store, helped to organize the Retail Merchants Association of Texas. Abraham Teah served on the board of the local school district and was a director of the First National Bank. Leo Davidson, a prominent dry goods merchant and cotton buyer, also served on the Palestine School Board. Clearly, many Jewish residents became civic and mercantile leaders in Palestine and helped shape the budding city and its growing economy.

Jews were so important in the city’s business sector that a newspaper on the first day of Rosh Hashanah in 1904, stated: “things look a little sleepy with the Jewish stores closed.” A similar notice appeared on Yom Kippur in 1909 claiming the town looked “dull.” The Jews’ devotion to their faith, even at the expense of the town’s economy, drew praise from the local newspaper. The Palestine Daily Herald noted in 1906 that Christians could learn “a lesson” from the local Jews whose “fidelity” in the observance of Rosh Hashanah meant their refusal to conduct any business.

Upon visiting Palestine in 1879, newspaper editor Charles Wessolowsky noted the zeal with which Jewish residents “engaged in business.” Wessolowsky, too, noted that the Jews of Palestine, satisfied and happy in their current environment, omitted the traditional recitation of the line “next year in Jerusalem” from the Passover Haggadah. However, Wessolowsky bemoaned the fact that, despite the presence of 11 Jewish families and 100 total Jews, no Jewish organizations existed. Perhaps due to his expression of concern, that fact soon changed.

In the early 1880s, the Jews of Palestine finally began organizing themselves formally. An 1882 newspaper article noted that High Holiday services were held in the Masonic Temple with a sermon delivered by Manuel Winner. Winner, a German immigrant, was a jeweler and watchmaker by trade. For many years, though referred to as “rabbi” or “reverend” by newspapers, Winner served the Jews of Palestine as lay leader. Winner performed weddings as well as High Holiday services, including those in 1885 held at Library Hall. Sometime prior to 1883, local Jews founded the Palestine Hebrew Association. In April, 1883, Michael Ash purchased an acre of land and deeded it, alongside part of another tract, to the association. This land became the Jewish cemetery and, upon Ash’s death in May, 1883, his will bequeathed funds for the continued upkeep of the burial ground in which he was laid to rest. Jewish communities in other towns utilized the cemetery as well and individuals from Bryan, Crockett, Henderson, Oakwoods, and Tyler are buried there. Henderson native Charles L. Brachfield, a former state senator and district and county judge, was buried in the Palestine Jewish cemetery.

Leaders in the Community

In addition to creating Jewish institutions, the Jews of Palestine were also taking part in the development of the city itself. Palestine’s growth in the late 19th century can be attributed mainly to the railroad’s arrival in the early 1870s. By the 1880s and 1890s, crops were being shipped out of Palestine as new businesses began to spring up around the railroad tracks. By the 1890s, Palestine’s population reached 9,000 people. In 1879, Wessolosky noted the role the Jews of Palestine were playing in the “building up” of the city. Similarly, Henry Ash’s 1903 obituary claimed that “Mr. Ash has always been identified with the progress and uplifting of Palestine and was one of the leading spirits in promoting its growth.” Phil Myers, a partner in the Grand Leader Department Store, helped to organize the Retail Merchants Association of Texas. Abraham Teah served on the board of the local school district and was a director of the First National Bank. Leo Davidson, a prominent dry goods merchant and cotton buyer, also served on the Palestine School Board. Clearly, many Jewish residents became civic and mercantile leaders in Palestine and helped shape the budding city and its growing economy.

Jews were so important in the city’s business sector that a newspaper on the first day of Rosh Hashanah in 1904, stated: “things look a little sleepy with the Jewish stores closed.” A similar notice appeared on Yom Kippur in 1909 claiming the town looked “dull.” The Jews’ devotion to their faith, even at the expense of the town’s economy, drew praise from the local newspaper. The Palestine Daily Herald noted in 1906 that Christians could learn “a lesson” from the local Jews whose “fidelity” in the observance of Rosh Hashanah meant their refusal to conduct any business.

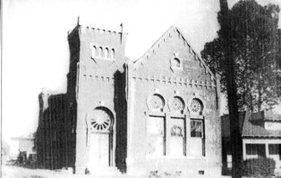

Beth Israel's synagogue, completed in 1901

Beth Israel's synagogue, completed in 1901

A Congregation and a Synagogue

As Palestine Jews established successful businesses, they began to discuss constructing a synagogue. The fundraising effort had begun in the 1880s. In 1883, Michael Ash left money for a synagogue in his will. Two years later, Palestine Jews held an elegant Purim Masquerade Ball at the Temple Opera House to raise money for a synagogue. However, a formal fundraising campaign was not started until 1900. It was soon successful and by April of that year, they bought a plot of land on the corner of Magnolia and Dallas Streets. The synagogue, dedicated to the memory of Michael Ash, was completed on the site in 1901. The Palestine Daily Circular described the synagogue as a “magnificent house of worship” and “one of the most beautiful and elegantly constructed architectural buildings in Texas.” Around the same time that they dedicated the synagogue, 25 Palestine Jews formally established the congregation Beth Israel.

In its first ten years, Beth Israel was served by various rabbis. Reform Rabbi L. Weiss led the congregation from 1901 until 1904. Following Rabbi Weiss’ tenure, the Palestine Daily Herald reported in 1905 that Rosh Hashanah services would be conducted by Rabbi Alfred Godshaw of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations of Cincinnati, Ohio. Rabbi Henry Cohen from Galveston and rabbis from other Texas congregations also served Beth Israel when possible. Lack of a full-time rabbi following Rabbi Weiss’ departure, however, did not prevent organizational developments within Beth Israel. By 1905, the congregation, which met on holidays and held services in English, had affiliated with the UAHC. Also by 1907, a Ladies Auxiliary of Beth Israel Congregation and a B’nai B’rith chapter had been founded. In 1907, Beth Israel had a Sunday School with four classes and 20 students.

By 1910, Beth Israel had dropped its membership in the UAHC, most likely for economic rather than ideological reasons. Around the same time, the congregation hired Rabbi Solomon Schaumberg, a German native, as their spiritual leader. Rabbi Schaumberg served the congregation until 1930 when his eyesight began to fail and he was forced to resign. He was followed by Rabbi Gottlieb. In years when Beth Israel did not have a rabbi, visiting rabbis or lay leaders, such as congregation president Leo Davidson, led holiday services. In 1935, Hyman Ettlinger, a mathematics professor at the University of Texas who often served as a lay rabbi around the state, led High Holiday services in Palestine.

As Palestine Jews established successful businesses, they began to discuss constructing a synagogue. The fundraising effort had begun in the 1880s. In 1883, Michael Ash left money for a synagogue in his will. Two years later, Palestine Jews held an elegant Purim Masquerade Ball at the Temple Opera House to raise money for a synagogue. However, a formal fundraising campaign was not started until 1900. It was soon successful and by April of that year, they bought a plot of land on the corner of Magnolia and Dallas Streets. The synagogue, dedicated to the memory of Michael Ash, was completed on the site in 1901. The Palestine Daily Circular described the synagogue as a “magnificent house of worship” and “one of the most beautiful and elegantly constructed architectural buildings in Texas.” Around the same time that they dedicated the synagogue, 25 Palestine Jews formally established the congregation Beth Israel.

In its first ten years, Beth Israel was served by various rabbis. Reform Rabbi L. Weiss led the congregation from 1901 until 1904. Following Rabbi Weiss’ tenure, the Palestine Daily Herald reported in 1905 that Rosh Hashanah services would be conducted by Rabbi Alfred Godshaw of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations of Cincinnati, Ohio. Rabbi Henry Cohen from Galveston and rabbis from other Texas congregations also served Beth Israel when possible. Lack of a full-time rabbi following Rabbi Weiss’ departure, however, did not prevent organizational developments within Beth Israel. By 1905, the congregation, which met on holidays and held services in English, had affiliated with the UAHC. Also by 1907, a Ladies Auxiliary of Beth Israel Congregation and a B’nai B’rith chapter had been founded. In 1907, Beth Israel had a Sunday School with four classes and 20 students.

By 1910, Beth Israel had dropped its membership in the UAHC, most likely for economic rather than ideological reasons. Around the same time, the congregation hired Rabbi Solomon Schaumberg, a German native, as their spiritual leader. Rabbi Schaumberg served the congregation until 1930 when his eyesight began to fail and he was forced to resign. He was followed by Rabbi Gottlieb. In years when Beth Israel did not have a rabbi, visiting rabbis or lay leaders, such as congregation president Leo Davidson, led holiday services. In 1935, Hyman Ettlinger, a mathematics professor at the University of Texas who often served as a lay rabbi around the state, led High Holiday services in Palestine.

Civic Engagement

Palestine Jews maintained their commercial and civic influence within the city during the early 20th century. Harry Myers ran the Grand Leader Department Store in the early 20th century and was a leader with the local Chamber of Commerce. Also an attorney, Myers served as president of the Palestine Bar Association. He was named “Mr. Palestine” for his extensive civic involvement. Jews’ success in Palestine during the height of a period marked by Ku Klux Klan activity illustrates how well they were received in the city. According to one contemporary estimate of the early 1920s, while Beth Israel’s membership numbered 40, the Klan, by far the largest “Fraternal Organization,” in Palestine, boasted 1,125 members. However, there are no reports of local Jews facing any prejudice or discrimination. Jews were among Palestine’s most notable citizens, involved in the commercial, civic, and social leadership of the city.

Palestine Jews maintained their commercial and civic influence within the city during the early 20th century. Harry Myers ran the Grand Leader Department Store in the early 20th century and was a leader with the local Chamber of Commerce. Also an attorney, Myers served as president of the Palestine Bar Association. He was named “Mr. Palestine” for his extensive civic involvement. Jews’ success in Palestine during the height of a period marked by Ku Klux Klan activity illustrates how well they were received in the city. According to one contemporary estimate of the early 1920s, while Beth Israel’s membership numbered 40, the Klan, by far the largest “Fraternal Organization,” in Palestine, boasted 1,125 members. However, there are no reports of local Jews facing any prejudice or discrimination. Jews were among Palestine’s most notable citizens, involved in the commercial, civic, and social leadership of the city.

The Community Declines

During the early 20th century, Palestine’s population swelled, reaching 11,000 people by 1914. However, the Jewish population did not grow much at all; there were an estimated 97 Jews in 1901 and 95 in 1919. Only a few Jewish families arrived in Palestine in the early 20th century compared to the much larger number of Jews who settled in the city in the late 19th century. Those who came in the 20th century followed the pattern set by their predecessors, opening dry goods stores. In the 1900s, Sam Brooks, a Romanian immigrant, opened “The Fashion” and Joe Chotiner, whose brother Max had arrived in the late 19th century, joined his brother in business, opening Chotiner Brothers Dry Goods Store by 1911. Other new Jewish residents included Ralph Hart, a prominent cotton buyer who brought professional baseball to Palestine in the 1920s, and Morris Pearlman, who came in 1914 and built an extremely successful salvage-hardware business. A small number of Jews settled in Palestine in the 1920s, including the merchants William Kelfer, Abraham Skuy and Abe Roth, all of whom were born in Russia. In 1927, an estimated 120 Jews lived in Palestine.

Over the next decade, the Jewish community went into sharp decline. Though the economy of Palestine had survived the Great Depression thanks to the discovery of oil nearby in 1928, the Jewish community shrank due to the lack of the new arrivals and the moving away of many of the Jewish children raised in Palestine. Thus, with Palestine’s young Jewish population leaving for larger cities like Dallas, El Paso, San Antonio, and New York City, the Jewish population of Palestine fell dramatically to only 56 people in 1937 as the community faded away. By 1940, Beth Israel closed its doors as the congregation disbanded. The synagogue was sold in 1950 and demolished in 1964. Some of the Jews who remained in Palestine following Beth Israel’s closing joined other congregations in the area. Morris Pearlman attended synagogue in Kilgore while Henry Leon joined Temple Beth El in Tyler.

The Jewish community of Palestine was almost resuscitated in the mid-1990s. A group of Southern Baptists, led by former minister Mike Flanagan, grew disenchanted with their Christian faith and began studying Jewish law and observing Jewish customs and holidays. Though not yet Jewish, many of these hopeful-converts faced anti-Semitism in Palestine, prompting ex-pastor Flanagan to move to Flatbush, New York, where he and wife Janice, renamed Yitzchak and Rivka Abrams, achieved an Orthodox conversion and remarried as Jews.

During the early 20th century, Palestine’s population swelled, reaching 11,000 people by 1914. However, the Jewish population did not grow much at all; there were an estimated 97 Jews in 1901 and 95 in 1919. Only a few Jewish families arrived in Palestine in the early 20th century compared to the much larger number of Jews who settled in the city in the late 19th century. Those who came in the 20th century followed the pattern set by their predecessors, opening dry goods stores. In the 1900s, Sam Brooks, a Romanian immigrant, opened “The Fashion” and Joe Chotiner, whose brother Max had arrived in the late 19th century, joined his brother in business, opening Chotiner Brothers Dry Goods Store by 1911. Other new Jewish residents included Ralph Hart, a prominent cotton buyer who brought professional baseball to Palestine in the 1920s, and Morris Pearlman, who came in 1914 and built an extremely successful salvage-hardware business. A small number of Jews settled in Palestine in the 1920s, including the merchants William Kelfer, Abraham Skuy and Abe Roth, all of whom were born in Russia. In 1927, an estimated 120 Jews lived in Palestine.

Over the next decade, the Jewish community went into sharp decline. Though the economy of Palestine had survived the Great Depression thanks to the discovery of oil nearby in 1928, the Jewish community shrank due to the lack of the new arrivals and the moving away of many of the Jewish children raised in Palestine. Thus, with Palestine’s young Jewish population leaving for larger cities like Dallas, El Paso, San Antonio, and New York City, the Jewish population of Palestine fell dramatically to only 56 people in 1937 as the community faded away. By 1940, Beth Israel closed its doors as the congregation disbanded. The synagogue was sold in 1950 and demolished in 1964. Some of the Jews who remained in Palestine following Beth Israel’s closing joined other congregations in the area. Morris Pearlman attended synagogue in Kilgore while Henry Leon joined Temple Beth El in Tyler.

The Jewish community of Palestine was almost resuscitated in the mid-1990s. A group of Southern Baptists, led by former minister Mike Flanagan, grew disenchanted with their Christian faith and began studying Jewish law and observing Jewish customs and holidays. Though not yet Jewish, many of these hopeful-converts faced anti-Semitism in Palestine, prompting ex-pastor Flanagan to move to Flatbush, New York, where he and wife Janice, renamed Yitzchak and Rivka Abrams, achieved an Orthodox conversion and remarried as Jews.

The Jewish Community in Palestine Today

The last recorded Jews in Palestine, shoe store owner Henry Leon and his wife Diane, arrived in 1938, two years prior to Beth Israel’s closing. Their son, Larry, the last Jewish graduate of Palestine High School, moved to Dallas as an adult. Both Henry and Diane were involved in the preservation and upkeep of the Beth Israel Cemetery and Henry was buried there in 1986. Diane, the last Jewish resident of Palestine, passed away in 2002. Hers remains the last burial in the Jewish cemetery.

Today, Temple Beth Israel Cemetery in Palestine remains the final testament to what was once a thriving Jewish presence in the city. The cemetery sits mostly empty, its open expanse revealing the anticipated growth and longevity of the Jews of Palestine that never came to be. Though there is no longer a Jewish presence in Palestine, the remarkable impact Jews have had on the city cannot be undone.

Today, Temple Beth Israel Cemetery in Palestine remains the final testament to what was once a thriving Jewish presence in the city. The cemetery sits mostly empty, its open expanse revealing the anticipated growth and longevity of the Jews of Palestine that never came to be. Though there is no longer a Jewish presence in Palestine, the remarkable impact Jews have had on the city cannot be undone.