Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Port Arthur, Texas

Port Arthur: Historical Overview

Stretching for 83 square miles along the west bank of Sabine Lake, just shy of the Louisiana border, Port Arthur, Texas, has undergone a series of radical shifts in population and character since its incorporation in 1898.Coming of age in the era of the Texas oil boom, Port Arthur sits only 20 miles southwest of Beaumont, Texas, home of Spindletop’s Lucas gusher, which first brought money-seekers to the area in droves. Port Arthur became the site of the early 20th century’s largest refinery complex, an industry which still employs many in the area. However, white-flight, hurricane devastation and a pattern of economic busts and booms have chipped away at the city center, leaving only hints of its former opulence. Much of the economic development that flourished in the downtown business district has shifted in the past 20 years to distant neighborhoods and beyond the city limits, leaving the once-burgeoning Proctor Street a relative ghost town.

Port Arthur’s Jewish community has followed a parallel path of decline and relocation, as the young migrate to suburbs and major urban centers, abandoning the family stores that once dominated city commerce. The synagogue Rodef Shalom now bears the name “Templo Shalom,” and has been in use as a church for over ten years. Still, in its heyday, Port Arthur’s Jewish community was vibrant. Existing in close proximity to the much larger Beaumont congregations, Port Arthurian Jews maintained a surprising amount of independence from their neighbors.

Port Arthur sprung forth from the plans of railroad magnate Arthur Stillwell, the founder of the Kansas City Suburban Belt Railway, which stretched from Kansas City, Kansas, to Independence, Missouri. His ambition from the beginning was to expand the rail through to the gulf coast. Stillwell needed a nexus of tourism and industry to serve as the final stop on his completed track, and he selected the area that was to become Port Arthur. By 1890, the track had been renamed the Kansas City Southern Railroad, and by 1895, settlement had begun in the area. Port Arthur became incorporated by 1898. Soon afterward, the Port Arthur Channel and Dock Co. (owned by Stillwell) began digging a canal along the western side of Sabine Lake, and in 1899, the port was opened to seagoing trade. On January 10th 1901, oil was struck by Captain Anthony F. Lucas and his crew at Beaumont. 100,000 barrels of oil a day shot out from the gusher at Spindletop, and profit-seeking migration also boomed in the region. Gulf Oil Corporation and Texaco set up refineries along the lake by 1902, and by the late 1950s, the petrochemical industry had become the backbone of the city economy.

Port Arthur’s Jewish community has followed a parallel path of decline and relocation, as the young migrate to suburbs and major urban centers, abandoning the family stores that once dominated city commerce. The synagogue Rodef Shalom now bears the name “Templo Shalom,” and has been in use as a church for over ten years. Still, in its heyday, Port Arthur’s Jewish community was vibrant. Existing in close proximity to the much larger Beaumont congregations, Port Arthurian Jews maintained a surprising amount of independence from their neighbors.

Port Arthur sprung forth from the plans of railroad magnate Arthur Stillwell, the founder of the Kansas City Suburban Belt Railway, which stretched from Kansas City, Kansas, to Independence, Missouri. His ambition from the beginning was to expand the rail through to the gulf coast. Stillwell needed a nexus of tourism and industry to serve as the final stop on his completed track, and he selected the area that was to become Port Arthur. By 1890, the track had been renamed the Kansas City Southern Railroad, and by 1895, settlement had begun in the area. Port Arthur became incorporated by 1898. Soon afterward, the Port Arthur Channel and Dock Co. (owned by Stillwell) began digging a canal along the western side of Sabine Lake, and in 1899, the port was opened to seagoing trade. On January 10th 1901, oil was struck by Captain Anthony F. Lucas and his crew at Beaumont. 100,000 barrels of oil a day shot out from the gusher at Spindletop, and profit-seeking migration also boomed in the region. Gulf Oil Corporation and Texaco set up refineries along the lake by 1902, and by the late 1950s, the petrochemical industry had become the backbone of the city economy.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Port Arthur

Early Settlers

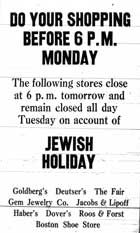

Like the city’s other early settlers, Jews were drawn by the opportunities Texas had to offer to the ambitious entrepreneur. While some were attracted by the promise of working in the refineries, most Jews came with hopes of opening businesses catering to the growing number of workers in the area. As was the story with many Texas towns, Jews became almost synonymous with retail trade in Port Arthur. Whether it was the Bagelman family’s shoe store, the Jacobs’ Gem Jewelry Co., Goldberg’s, Deuster’s, The Fair, Jacobs and Lipoff, Haber’s, Dover’s, Roos & Forst, or the Boson Shoe Store, an estimated 75% of the businesses that would thrive on Proctor Street throughout Port Arthur’s history were owned and operated by Jewish merchants.

Abe Goldberg was among Port Arthur’s earliest Jewish settlers. Leaving Russia in 1895, Goldberg settled initially in Hearne, Texas, where he opened a business. He later moved to Bryan and then Sabine Pass. The damage caused by the storm of 1900 all but halted business in Sabine Pass, compelling Goldberg’s final move to Port Arthur. He opened up a general merchandising store on the corner of Fourth and San Antonio Streets. Through a partnership with E. Deuster, the store expanded, and Goldberg gained a reputation for providing the most fashionable and up-to-date goods in town. He was able to amass a comfortable fortune, which he channeled back into the community through charitable contributions. Goldberg frequently appears in area newspapers as one of the community’s most prominent philanthropists. Goldberg is perhaps best remembered as the founder of both the Texas Society for Crippled Children and the Thomas W. Hughen School for Crippled Children.

In 1911, Louis Mandel arrived in Galveston from Kretinga, Russia at the age of 13. After living with an uncle in Jefferson, Texas, for a short while, he moved to Port Arthur. Another uncle, Sam Segal, already owned a furniture store on Proctor Street, and would give the young Louis the experience necessary to succeed in the business. In 1933, Mandel opened his own shop on Proctor Street, dealing initially in furniture and radios. Mandel gained a reputation as a music aficionado and horse lover—even racing one of his favorite mounts down Proctor Street when it was still what one journalist called a “dusty track.” However, in the 1940s, tragedy struck the family. Kretinga fell under Nazi control, putting Louis’ parents and seven younger siblings in danger. With the exception of one sister who escaped to Siberia, much of the family was lost in the Holocaust. However, Louis’ youngest sister, Frieda Ellberg, was also saved. Along with her parents and siblings, Ellberg had also lost her husband during the war. Frieda had allegedly survived due to her ability to speak several languages fluently, which made her an asset to the Nazis. Though Louis had not seen Frieda since he was 13 years old, and the two barely remembered what each other looked like, he was dedicated to getting his youngest sister out of Kretinga. Louis’ personal attorney, J.W. “Judge” Williams, and his legal secretary, Helen McCurdy, were responsible for compiling much of the paperwork necessary to bring Ellberg to Port Arthur, and she arrived safely in 1948. Both Louis and Frieda would run Mandel’s in partnership from that day forward until 1991, when the brother and sister team retired at the ages of 91 and 80, respectively.

Like the city’s other early settlers, Jews were drawn by the opportunities Texas had to offer to the ambitious entrepreneur. While some were attracted by the promise of working in the refineries, most Jews came with hopes of opening businesses catering to the growing number of workers in the area. As was the story with many Texas towns, Jews became almost synonymous with retail trade in Port Arthur. Whether it was the Bagelman family’s shoe store, the Jacobs’ Gem Jewelry Co., Goldberg’s, Deuster’s, The Fair, Jacobs and Lipoff, Haber’s, Dover’s, Roos & Forst, or the Boson Shoe Store, an estimated 75% of the businesses that would thrive on Proctor Street throughout Port Arthur’s history were owned and operated by Jewish merchants.

Abe Goldberg was among Port Arthur’s earliest Jewish settlers. Leaving Russia in 1895, Goldberg settled initially in Hearne, Texas, where he opened a business. He later moved to Bryan and then Sabine Pass. The damage caused by the storm of 1900 all but halted business in Sabine Pass, compelling Goldberg’s final move to Port Arthur. He opened up a general merchandising store on the corner of Fourth and San Antonio Streets. Through a partnership with E. Deuster, the store expanded, and Goldberg gained a reputation for providing the most fashionable and up-to-date goods in town. He was able to amass a comfortable fortune, which he channeled back into the community through charitable contributions. Goldberg frequently appears in area newspapers as one of the community’s most prominent philanthropists. Goldberg is perhaps best remembered as the founder of both the Texas Society for Crippled Children and the Thomas W. Hughen School for Crippled Children.

In 1911, Louis Mandel arrived in Galveston from Kretinga, Russia at the age of 13. After living with an uncle in Jefferson, Texas, for a short while, he moved to Port Arthur. Another uncle, Sam Segal, already owned a furniture store on Proctor Street, and would give the young Louis the experience necessary to succeed in the business. In 1933, Mandel opened his own shop on Proctor Street, dealing initially in furniture and radios. Mandel gained a reputation as a music aficionado and horse lover—even racing one of his favorite mounts down Proctor Street when it was still what one journalist called a “dusty track.” However, in the 1940s, tragedy struck the family. Kretinga fell under Nazi control, putting Louis’ parents and seven younger siblings in danger. With the exception of one sister who escaped to Siberia, much of the family was lost in the Holocaust. However, Louis’ youngest sister, Frieda Ellberg, was also saved. Along with her parents and siblings, Ellberg had also lost her husband during the war. Frieda had allegedly survived due to her ability to speak several languages fluently, which made her an asset to the Nazis. Though Louis had not seen Frieda since he was 13 years old, and the two barely remembered what each other looked like, he was dedicated to getting his youngest sister out of Kretinga. Louis’ personal attorney, J.W. “Judge” Williams, and his legal secretary, Helen McCurdy, were responsible for compiling much of the paperwork necessary to bring Ellberg to Port Arthur, and she arrived safely in 1948. Both Louis and Frieda would run Mandel’s in partnership from that day forward until 1991, when the brother and sister team retired at the ages of 91 and 80, respectively.

The Deutser and Goldberg store

The Deutser and Goldberg store

Organized Jewish Life in Port Arthur

While there is no record of exactly when formal services began in Port Arthur’s Jewish community, a small congregation had begun worshiping in private homes in the 1910s. By 1922 the congregation was able to rent space above the Kress building on Proctor Street, though these services were still led by laymen. It wasn’t until 1930 that the group was able to purchase a former Congregational Christian Church on the corner of Mobile Avenue and Sixth Street. This church had been built in the early 1900s and initially housed a Lutheran congregation. The building was then sold to the Congregational Christian Church, after which it was purchased by the Jewish community. The local Jewish community originally intended to use it as a community center, but the building was soon transformed into a synagogue after the group established themselves as Congregation Rodef Shalom.

While there is no record of exactly when formal services began in Port Arthur’s Jewish community, a small congregation had begun worshiping in private homes in the 1910s. By 1922 the congregation was able to rent space above the Kress building on Proctor Street, though these services were still led by laymen. It wasn’t until 1930 that the group was able to purchase a former Congregational Christian Church on the corner of Mobile Avenue and Sixth Street. This church had been built in the early 1900s and initially housed a Lutheran congregation. The building was then sold to the Congregational Christian Church, after which it was purchased by the Jewish community. The local Jewish community originally intended to use it as a community center, but the building was soon transformed into a synagogue after the group established themselves as Congregation Rodef Shalom.

Louis Mandel (left) collecting

Louis Mandel (left) collecting accounts for his furniture store

While the Port Arthur congregation tended toward Reform Judaism, a small Orthodox group also existed. Early in the congregation’s history, the two groups quarreled over questions of ritual and tradition. The record shows that, for some time, the Orthodox group met separately for services. In 1935, these two factions split completely, with the Orthodox group founding Congregation Agudas Israel and holding separate meetings at Carpenter Hall on Seventh Street, only a short distance away from the original synagogue. Despite this schism, Rodef Shalom was able to hire its first full-time rabbi, Selwyn Ruslander, in 1936. The split was short-lived, as Rodef Shalom was reunified by the late 1930s. The congregation officially joined the Reform Union of American Hebrew Congregations by 1940. Renee Bennett's family was part of the Orthodox group, and attended Rodef Shalom for Friday night services, but Bennett remembers that separate Orthodox and Reform meetings were held for the High Holidays. The congregation’s Reform rabbi wore a yarmulke when he visited the Orthodox service, but removed it when he went to the Reform service. Whatever disputes existed between the two groups seem to have subsided by the time a new synagogue was constructed in 1951.

Rodef Shalom's synagogue,

Rodef Shalom's synagogue, constructed in 1951

Membership climbed steadily as the postwar economy boomed, and the congregation soon outgrew the former church on Sixth Street. Rodef Shalom had 60 member families in 1945, growing to 91 families by 1962. Equally significant was the movement of many Port Arthur Jews to the area east of downtown. The location chosen for the new temple at 3948 Proctor Street reflected both the need for a bigger space to house the congregation and the eastward migration of the Jewish community. The temple design was simple and functional and included much more space for worship and social activities. Included in the original design was a main sanctuary, an assembly hall, a kitchen, and classrooms. An extension was later added to accommodate more students in the Sunday school. In the congregation's busiest years, as many as 50 students attended classes.

Rodef Shalom was also home to many thriving temple organizations. Both the Sisterhood and the Council of Jewish Women were active in the community, and the Zionist movement was led by Dr. Harris Hosen, a local pediatrician. The Council of Jewish Women is remembered fondly by the community for their rummage and cake sales. The council routinely raised over $1,000 during its rummage sales, while the matzah ball soup and deli sandwiches the women made for fundraising would draw substantial crowds. The money raised by the council went toward the synagogue and school, but also to organizations throughout the city, notably those for underprivileged women.

Rodef Shalom was also home to many thriving temple organizations. Both the Sisterhood and the Council of Jewish Women were active in the community, and the Zionist movement was led by Dr. Harris Hosen, a local pediatrician. The Council of Jewish Women is remembered fondly by the community for their rummage and cake sales. The council routinely raised over $1,000 during its rummage sales, while the matzah ball soup and deli sandwiches the women made for fundraising would draw substantial crowds. The money raised by the council went toward the synagogue and school, but also to organizations throughout the city, notably those for underprivileged women.

Rabbi Alexander Kline

Rabbi Alexander Kline

Like other small congregations, Rodef Shalom suffered a high degree of turnover in its rabbinic leadership. After Rabbi Ruslander left in 1939, he was followed by Rabbi Alexander S. Kline, who only stayed in Port Arthur a few years. Despite his short tenure, Kline made a significant mark on the city’s cultural life, leading an art appreciation course that drew large audiences from throughout the region. On the roof of the Goodhue Hotel, Rabbi Kline would begin his survey with the Egyptians and continue through to Picasso and other modern masters. Kline reached out to the larger community through both art and media. In 1941, the Port Arthur News advertised that Rabbi Kline gave a lecture on the radio station KPAC for the High Holidays. The subject of the program was “What We Mean by Religion.” While the program offered an opportunity for contemplation and reflection to Jews during the holidays, it was also geared to the community at large. Kline was succeeded by a series of short-term rabbis until 1966, when Rabbi Lothar Goldstein came to Port Arthur.

Rabbi Goldstein was a Holocaust survivor and had lived in Peru for ten years prior to his arrival in Port Arthur. Much of his family had been lost in the Holocaust, and the experience of those years would motivate him to become an involved social activist. In Port Arthur, Goldstein was a charter member of the International Seaman’s Center, which provided services to sailors from around the world. Goldstein also wrote extensively, occasionally authoring articles for various newspapers and magazines, as well as several books. He lectured at the United Methodist Church and the School of Theology of the Episcopal Church in Houston on the Torah. Goldstein also held leadership positions in organizations dealing with psychoanalysis and mental health issues, as well as the Red Cross. Throughout his time at Rodef Shalom, Goldstein supplemented his income by maintaining a practice as a clinical psychologist. Goldstein’s wife Justina held a doctorate in psychology and spoke six languages fluently. Rabbi Goldstein led Rodef Shalom for two decades.

Rabbi Goldstein was a Holocaust survivor and had lived in Peru for ten years prior to his arrival in Port Arthur. Much of his family had been lost in the Holocaust, and the experience of those years would motivate him to become an involved social activist. In Port Arthur, Goldstein was a charter member of the International Seaman’s Center, which provided services to sailors from around the world. Goldstein also wrote extensively, occasionally authoring articles for various newspapers and magazines, as well as several books. He lectured at the United Methodist Church and the School of Theology of the Episcopal Church in Houston on the Torah. Goldstein also held leadership positions in organizations dealing with psychoanalysis and mental health issues, as well as the Red Cross. Throughout his time at Rodef Shalom, Goldstein supplemented his income by maintaining a practice as a clinical psychologist. Goldstein’s wife Justina held a doctorate in psychology and spoke six languages fluently. Rabbi Goldstein led Rodef Shalom for two decades.

Since the congregation disbanded,

Since the congregation disbanded, Rodef Shalom's temple has been

rented to church groups.

Growth and Decline

Port Arthur’s Jewish community grew in the post-war years, reaching an estimated 260 people by 1960. In addition to merchants, a number of Jewish scientists, engineers, and executives moved to town to work in the local petrochemical industry. Hymie Massin was the head of research for Texaco. Several Jewish doctors also moved to Port Arthur during this time, and became active in the local Jewish community.

Following a peak membership of 91 families in the early 1960s, Port Arthur’s congregation began three decades of slow decline. Rodef Shalom was strengthened by members who came from neighboring towns, like Orange, that did not have their own Jewish congregations.

By the 1980s, Port Arthur had gone into decline with its downtown business district largely closed. As the residential patterns of Port Arthur’s neighborhoods began major demographic shifts, refineries began advising new employees to move to commute rather than purchase homes near downtown. New suburban shopping centers with national chain stores moved into the area. Consequently, the clientele base for the town’s Jewish merchants became a non-renewing resource, and locally owned businesses began to shut their doors.

As a result of these changes, the congregation began to decline as well. Rabbi Goldstein passed away in the mid-1980s, and he was not replaced; members, including Rabbi Goldstein’s widow Justina, conducted services themselves for the next decade or so. Contributions from former members, especially families such as the Blankfields and Rosenbergs helped, but after the death of Justina Goldstein the congregation was too small to maintain the temple. Rodef Shalom, down to 28 member families, closed its doors in 1995.

Port Arthur’s Jewish community grew in the post-war years, reaching an estimated 260 people by 1960. In addition to merchants, a number of Jewish scientists, engineers, and executives moved to town to work in the local petrochemical industry. Hymie Massin was the head of research for Texaco. Several Jewish doctors also moved to Port Arthur during this time, and became active in the local Jewish community.

Following a peak membership of 91 families in the early 1960s, Port Arthur’s congregation began three decades of slow decline. Rodef Shalom was strengthened by members who came from neighboring towns, like Orange, that did not have their own Jewish congregations.

By the 1980s, Port Arthur had gone into decline with its downtown business district largely closed. As the residential patterns of Port Arthur’s neighborhoods began major demographic shifts, refineries began advising new employees to move to commute rather than purchase homes near downtown. New suburban shopping centers with national chain stores moved into the area. Consequently, the clientele base for the town’s Jewish merchants became a non-renewing resource, and locally owned businesses began to shut their doors.

As a result of these changes, the congregation began to decline as well. Rabbi Goldstein passed away in the mid-1980s, and he was not replaced; members, including Rabbi Goldstein’s widow Justina, conducted services themselves for the next decade or so. Contributions from former members, especially families such as the Blankfields and Rosenbergs helped, but after the death of Justina Goldstein the congregation was too small to maintain the temple. Rodef Shalom, down to 28 member families, closed its doors in 1995.

The Jewish Community in Port Arthur Today

Since the congregation disbanded, Rodef Shalom's temple has been rented to church groups. The remaining Jews of Port Arthur joined Temple Emanuel in nearby Beaumont, where they have become active members of the Reform congregation.