Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - San Antonio, Texas

Historical Overview

|

One of the oldest cities in Texas, San Antonio has a history that stretches back to 1718, when the Spanish established a military outpost to help prevent French incursions into New Spain. The Spanish constructed a presidio to house its soldiers and four missions to convert the native peoples in the area as a town soon sprang up around this initial settlement. The city became part of Mexico after that country gained its independence from Spain in 1821. Located in the remote northern region of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas, San Antonio, with its Alamo mission, became an important front in the battle for Texas independence. After the Texans established their republic, and were soon annexed to the United States, San Antonio flourished, becoming a center of the state’s livestock industry. A large wave of German immigrants came to the city in the mid-19th century. By 1870, German natives made up over one-third of the city population of 8,000 people. The first Jews to settle permanently in San Antonio were part of this German wave. The vibrant Jewish community in San Antonio today is rooted in these first immigrants.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in San Antonio

Jewish-owned stores on Main Plaza, c. 1870s. Photo

Jewish-owned stores on Main Plaza, c. 1870s. Photo courtesy of UTSA Libraries Special Collections.

Early Settlers

According to local historian Frances Kallison, the first Jew to settle in San Antonio was Prussian immigrant Louis Zork, who was living in the city with his wife Adele by 1847. Zork opened a store by 1851, later adding a wholesale operation. Zork’s business was quite successful as by 1860 he had over $50,000 in personal wealth. By 1867, Zork was a director of the San Antonio National Bank. Taking advantage of life in a small town with a burgeoning immigrant population, Zork was able to move quickly into civic and political leadership. He served as a city alderman from 1856 to 1857, and was elected treasurer of Bexar County, a position he held from 1856 to 1865.

Zork was one of a handful of German Jews who lived in San Antonio in the 1850s. According to Kallison, about ten or 11 Jewish families lived in the city by the end of the decade. Henry Mayer owned a store in San Antonio by 1852; by 1860, he owned $10,000 worth of real estate and $15,000 in personal estate. In 1855, San Antonio Jews bought land for a cemetery, founding the Hebrew Benevolent Society the following year. Both Mayer and Zork were leaders of this nascent Jewish community. Mayer held perhaps the first Jewish religious services in the city at his home, though this small community did not meet regularly. Zork raised $59 from the few Jews in San Antonio to donate to the newly founded Jewish Widows and Orphans Home in New Orleans in 1858.

The Civil War was a turning point for the San Antonio Jewish community. On the one hand, it created significant challenges for the fledgling community. Opponents of secession, Henry Mayer and his family left San Antonio after Confederate forces took charge of the city, while the Hebrew Benevolent Society became inactive during the war. Yet after the South’s surrender, the Jewish community began to thrive, along with the rest of the city. Growing numbers of Jews were drawn to San Antonio as the city became the economic gateway to Mexico. This trade with Mexico, at first conducted via mule train and after 1877 by railroad, brought new economic vitality to the area. San Antonio also became a major supply depot for the many military outposts in the region. The Jewish community of San Antonio grew quickly in the post war years. In 1866, local Jews reorganized the Hebrew Benevolent Society, which cared for their sick and poor co-religionists. The society was officially chartered in 1871, and later became known as the Montefiore Benevolent Society.

According to local historian Frances Kallison, the first Jew to settle in San Antonio was Prussian immigrant Louis Zork, who was living in the city with his wife Adele by 1847. Zork opened a store by 1851, later adding a wholesale operation. Zork’s business was quite successful as by 1860 he had over $50,000 in personal wealth. By 1867, Zork was a director of the San Antonio National Bank. Taking advantage of life in a small town with a burgeoning immigrant population, Zork was able to move quickly into civic and political leadership. He served as a city alderman from 1856 to 1857, and was elected treasurer of Bexar County, a position he held from 1856 to 1865.

Zork was one of a handful of German Jews who lived in San Antonio in the 1850s. According to Kallison, about ten or 11 Jewish families lived in the city by the end of the decade. Henry Mayer owned a store in San Antonio by 1852; by 1860, he owned $10,000 worth of real estate and $15,000 in personal estate. In 1855, San Antonio Jews bought land for a cemetery, founding the Hebrew Benevolent Society the following year. Both Mayer and Zork were leaders of this nascent Jewish community. Mayer held perhaps the first Jewish religious services in the city at his home, though this small community did not meet regularly. Zork raised $59 from the few Jews in San Antonio to donate to the newly founded Jewish Widows and Orphans Home in New Orleans in 1858.

The Civil War was a turning point for the San Antonio Jewish community. On the one hand, it created significant challenges for the fledgling community. Opponents of secession, Henry Mayer and his family left San Antonio after Confederate forces took charge of the city, while the Hebrew Benevolent Society became inactive during the war. Yet after the South’s surrender, the Jewish community began to thrive, along with the rest of the city. Growing numbers of Jews were drawn to San Antonio as the city became the economic gateway to Mexico. This trade with Mexico, at first conducted via mule train and after 1877 by railroad, brought new economic vitality to the area. San Antonio also became a major supply depot for the many military outposts in the region. The Jewish community of San Antonio grew quickly in the post war years. In 1866, local Jews reorganized the Hebrew Benevolent Society, which cared for their sick and poor co-religionists. The society was officially chartered in 1871, and later became known as the Montefiore Benevolent Society.

Mayer Halff

Mayer Halff

Several Jews who came to San Antonio after the war amassed significant fortunes. Alsatian-born Mayer Halff came to America in 1850, when he was just 14 years old. After peddling with his older brother out of Liberty, Texas, the two opened a store in the town in 1856. After his brother tragically drowned, Mayer brought over his younger brother Solomon to help him in the business. The two moved to San Antonio in 1865, opening a large dry goods operation called M. Halff & Bros. When some of their customers offered to pay their bills in cattle, the Halff brothers moved into 19th century Texas’ most famous industry: ranching. Solomon ran the wholesale dry goods business, which became the largest supply house in the southwest, while Mayer focused on their cattle interests. Mayer bought several ranches in west Texas; at their peak, the Halff brothers owned over a million acres of land while their ranches were the third largest producer of cattle in the country. They were among the first ranchers to bring Hereford cattle to Texas. While their cattle interests were in West Texas, the brothers resided in San Antonio, becoming leading figures in the city’s business community. Solomon Halff helped to organize Alamo National Bank, becoming as its first vice president, while Mayer helped found City National Bank, serving as its president. The Halff’s ranching empire did not continue long in the 20th century. Solomon left the business in 1900, and Mayer’s sons eventually sold off most of their ranching interests.

Daniel Oppenheimer.

Daniel Oppenheimer. Photo courtesy of Temple Beth-El

Daniel and Anton Oppenheimer were another set of brothers who branched out beyond the dry goods counter. They came to Texas from Bavaria in the 1850s. After fighting for the Confederacy, the brothers moved to San Antonio and opened a general store. According to the San Antonio Express in 1880, their store, D. & A. Oppenheimer “is one of our best known dry goods houses. They transact an enormous business and are known in mostly every household in Western Texas.” In the late 19th century, Texas law banned state banks, and so many of the Oppenheimers’ customers asked to keep their money in the store’s safe. Ranchers also used such merchants to front them credit for their endeavors. This banking service to their store customers soon grew into a side business. Around the turn of the century, the brothers closed their store to focus on their banking business. D. & A. Oppenheimer remained a private bank; it did not belong to the Federal Reserve and did not have FDIC protection. Such private banks were later banned in Texas, but the D & A Oppenheimer bank was allowed to continue since it predated the law. The bank remained a family business, with Dan’s son Jesse later running it. Dan’s grandson Herbert Oppenheimer, its last president, decided to liquidate the bank in 1988 when there was no longer anyone in the family who wanted to run the business.

Julius Joske came to San Antonio by himself in 1867, opening a small dry goods store. Once he was established economically, he sold the store and returned to Germany to retrieve his wife and four children. Bringing them back to San Antonio in 1873, he opened a new store, which grew into the largest department store in the region. Joske’s great innovation was the introduction of penny pricing. Previously, stores in San Antonio sold merchandise at five cent intervals, with a nickel being their lowest price. In 1886, Joske announced the new penny pricing and their receipt of a huge supply of copper pennies from the United States mint to make change for their customers who would now get a few cents back instead of prices being rounded up the nearest nickel. Despite its penny pricing, J. Joske was not a discount store; at the same time they advertised their new pricing policy, they also announced their hiring of a permanent New York buyer who would send the latest big city fashions to the San Antonio store. Joske’s sons Alexander and Siegfried joined the business, which later became known as Joske Brothers. Alexander bought out his brother in 1903 and greatly expanded the store. In 1929, the store was sold, and was later bought by Allied Stores, who built Joske’s into a chain of department stores across Texas.

Julius Joske came to San Antonio by himself in 1867, opening a small dry goods store. Once he was established economically, he sold the store and returned to Germany to retrieve his wife and four children. Bringing them back to San Antonio in 1873, he opened a new store, which grew into the largest department store in the region. Joske’s great innovation was the introduction of penny pricing. Previously, stores in San Antonio sold merchandise at five cent intervals, with a nickel being their lowest price. In 1886, Joske announced the new penny pricing and their receipt of a huge supply of copper pennies from the United States mint to make change for their customers who would now get a few cents back instead of prices being rounded up the nearest nickel. Despite its penny pricing, J. Joske was not a discount store; at the same time they advertised their new pricing policy, they also announced their hiring of a permanent New York buyer who would send the latest big city fashions to the San Antonio store. Joske’s sons Alexander and Siegfried joined the business, which later became known as Joske Brothers. Alexander bought out his brother in 1903 and greatly expanded the store. In 1929, the store was sold, and was later bought by Allied Stores, who built Joske’s into a chain of department stores across Texas.

Alexander Joske. Photo courtesy of Temple Beth-El

Alexander Joske. Photo courtesy of Temple Beth-El

Organized Jewish Life in San Antonio

As these German Jews established their businesses, they began to organize institutions to serve the city’s growing Jewish population. In 1870, women founded the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society, which worked to aid Jewish children and families in need. By 1882, the group had 30 members. Men started a local B’nai B’rith lodge in 1874. San Antonio Jews also started a fledgling Young Men’s Hebrew Association in 1879, though this group was short-lived. By 1872, San Antonio Jews were meeting together informally for prayer at Ruellman Hall.

Finally, in 1874, a group of 44 Jews established Congregation Beth-El. Most of these founders were relative newcomers to the city; of the 44 founders, only 9 were listed in the 1870 census as living in San Antonio. Of the 29 who could be located in the U.S. census of 1870 or 1880, all of them worked in retail or wholesale trade; 78% were merchants, while the remaining 22% worked as store clerks. Their average age was 36. The large majority of the founders, 84%, were immigrants, mostly from Germany, especially Bavaria and Prussia. Four of the founders came from France, while only two were Russian or Polish. Befitting the strongly German nature of the congregation, Beth-El was Reform from its founding, adopting Isaac Mayer Wise’s Minhag America prayer book. In 1874, the congregation voted 16 to 5 to ban head coverings for all worshipers except the rabbi. One member strongly objected to this rule and demanded that his opposition be noted in the minutes. Thus, while most members supported Reform, with Beth-El joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1875, there was still disagreement over ritual questions.

Despite these differences, Beth-El moved quickly to raise money for a house of worship, appointing a committee to solicit the Jewish communities of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia for contributions. This committee likely used its business ties in these northeastern cities to raise money for the building fund. By 1875, Beth-El was able to build a modest synagogue on Travis Square. For the dedication, Beth-El brought in Rabbi James Gutheim of New Orleans as the keynote speaker at an event that drew a large crowd of non-Jews. According to the local newspaper account, the crowd “was composed indiscriminately of Jews and Christians, Protestants and Catholics.” A choir, made up of Jews, Christian church choir members, and people from a local German singing society, performed during the event. Many San Antonio Jews belonged to the various German athletic and cultural organizations in the city. The local newspaper reprinted Rabbi Gutheim’s dedication address in its daily edition, rerunning it in the weekly edition due to popular demand.

As these German Jews established their businesses, they began to organize institutions to serve the city’s growing Jewish population. In 1870, women founded the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society, which worked to aid Jewish children and families in need. By 1882, the group had 30 members. Men started a local B’nai B’rith lodge in 1874. San Antonio Jews also started a fledgling Young Men’s Hebrew Association in 1879, though this group was short-lived. By 1872, San Antonio Jews were meeting together informally for prayer at Ruellman Hall.

Finally, in 1874, a group of 44 Jews established Congregation Beth-El. Most of these founders were relative newcomers to the city; of the 44 founders, only 9 were listed in the 1870 census as living in San Antonio. Of the 29 who could be located in the U.S. census of 1870 or 1880, all of them worked in retail or wholesale trade; 78% were merchants, while the remaining 22% worked as store clerks. Their average age was 36. The large majority of the founders, 84%, were immigrants, mostly from Germany, especially Bavaria and Prussia. Four of the founders came from France, while only two were Russian or Polish. Befitting the strongly German nature of the congregation, Beth-El was Reform from its founding, adopting Isaac Mayer Wise’s Minhag America prayer book. In 1874, the congregation voted 16 to 5 to ban head coverings for all worshipers except the rabbi. One member strongly objected to this rule and demanded that his opposition be noted in the minutes. Thus, while most members supported Reform, with Beth-El joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1875, there was still disagreement over ritual questions.

Despite these differences, Beth-El moved quickly to raise money for a house of worship, appointing a committee to solicit the Jewish communities of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia for contributions. This committee likely used its business ties in these northeastern cities to raise money for the building fund. By 1875, Beth-El was able to build a modest synagogue on Travis Square. For the dedication, Beth-El brought in Rabbi James Gutheim of New Orleans as the keynote speaker at an event that drew a large crowd of non-Jews. According to the local newspaper account, the crowd “was composed indiscriminately of Jews and Christians, Protestants and Catholics.” A choir, made up of Jews, Christian church choir members, and people from a local German singing society, performed during the event. Many San Antonio Jews belonged to the various German athletic and cultural organizations in the city. The local newspaper reprinted Rabbi Gutheim’s dedication address in its daily edition, rerunning it in the weekly edition due to popular demand.

Beth-El's first synagogue

Beth-El's first synagogue

During its early years, Beth-El often struggled financially. The congregation had to dismiss their first full-time spiritual leader, B.E. Jacobs, in 1878 when they could not afford to pay his salary. They were able to hire Rev. Isidore Lewinthal in 1879, but board members complained about the large number of Jews in the city who did not belong to the congregation. They even barred non-members from worshiping at Beth-El and prevented Lewinthal from officiating at non-member life cycle events. In 1892, these financial troubles came to a head as the congregation voted on the question of whether to disband or continue. Faced with this existential question, the members of Beth-El affirmed their desire to remain a congregation. After a series of short-term rabbis, in 1897 Beth-El hired Samuel Marks, who helped lead the congregation through a period of tremendous growth. By the turn of the century, the congregation had outgrown its small building, and Rabbi Marks pushed for a new synagogue, which was finally dedicated in 1903. Beth-El met at a Baptist Church while their new home was being completed.

By 1907, Beth-El had 120 members, up from just 33 members 20 years earlier. By the time Rabbi Marks retired in 1920, Beth-El had grown to 252 member families. Despite Beth-El’s flourishing during his time at the helm, Rabbi Marks’s tenure was sometimes controversial. In 1918, he criticized his congregation from the pulpit for not being more hospitable to Jewish soldiers stationed in the area. That same year, he aroused the ire of the temple board when he published an editorial in the local newspaper opposing alcohol prohibition.

The leadership of Beth-El did not want their rabbi weighing in on such controversial political issues and passed a resolution admonishing Marks. Despite this occasional tension, Rabbi Marks remained affiliated with Beth-El as Rabbi Emeritus for another 14 years. Ephraim Frisch became Beth-El’s rabbi in 1923, leading the congregation for the next two decades.

By 1907, Beth-El had 120 members, up from just 33 members 20 years earlier. By the time Rabbi Marks retired in 1920, Beth-El had grown to 252 member families. Despite Beth-El’s flourishing during his time at the helm, Rabbi Marks’s tenure was sometimes controversial. In 1918, he criticized his congregation from the pulpit for not being more hospitable to Jewish soldiers stationed in the area. That same year, he aroused the ire of the temple board when he published an editorial in the local newspaper opposing alcohol prohibition.

The leadership of Beth-El did not want their rabbi weighing in on such controversial political issues and passed a resolution admonishing Marks. Despite this occasional tension, Rabbi Marks remained affiliated with Beth-El as Rabbi Emeritus for another 14 years. Ephraim Frisch became Beth-El’s rabbi in 1923, leading the congregation for the next two decades.

Beth-El's second synagogue

Beth-El's second synagogue

The Community Grows

Only a few years after the city’s German Jews established Beth-El, a growing number of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe began to settle in San Antonio. Many had fled Russia after a wave of pogroms terrorized Jews in 1881. On January 5, 1882, the San Antonio Evening Light reported, “there have arrived in our city during the past two or three months fourteen Russian Jewish refugees.” The San Antonio Jewish community had formed a committee, led by B. Schwarz and Rabbi Lewinthal, to help these immigrants get settled. The paper noted that all of them, except for a widow and her three youngest children, had found employment in the city as manual laborers. The Light encouraged more Jewish refugees to come to Texas, writing “with our mild climate and growing country, they could certainly be helped sooner to secure homes and become self-supporting.”

While this group of Russian immigrants started out as manual laborers, others followed the same path as the earlier German Jewish immigrants, moving into retail trade. Sol Dalkowitz left Lithuania in 1881; after a few months in New York City, he moved south to San Antonio to join his older brother Julius. Both of them started out as peddlers, traveling on foot before acquiring a wagon. They covered the small towns within a 150-mile radius of San Antonio, and would be gone for a few months at a time. After about a year and a half of peddling, they opened a retail store, Dalkowitz Brothers, in San Antonio. Using the contacts they had made as traveling peddlers, Sol and Julius were able to establish a thriving wholesale operation, supplying stores in the small towns of the region.

When Sol Dalkowitz came to San Antonio in 1882, there were only a handful of Orthodox Jews in the city. But as their numbers grew, they began to establish their own religious organizations independent of Beth-El. In 1883, they founded a benevolent society called Gemilath Chasodim (Acts of Loving Kindness), which also held religious services. When they acquired a Torah scroll soon after forming, the society held a dedication ceremony to which they invited Rabbi Lewinthal of Beth-El. While Lewinthal attended the dedication, the local newspaper noted that he did not seem to support the formation of a competing congregation and refused to give the priestly blessing. During the group’s early years, they met for regular minyans at the home of Max Karotkin and at the Odd Fellows Hall for High Holiday services. In 1889, the group established a formal congregation called Agudas Achim (Society of Brothers) with Sol Koenigsberg as their first president. None of the 23 founders, most of whom were merchants, had been founders of Beth-El. This was not a breakaway from the Reform congregation, but rather a distinct group of recent immigrants who wished to worship according to the practices of Orthodox Judaism.

Only a few years after the city’s German Jews established Beth-El, a growing number of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe began to settle in San Antonio. Many had fled Russia after a wave of pogroms terrorized Jews in 1881. On January 5, 1882, the San Antonio Evening Light reported, “there have arrived in our city during the past two or three months fourteen Russian Jewish refugees.” The San Antonio Jewish community had formed a committee, led by B. Schwarz and Rabbi Lewinthal, to help these immigrants get settled. The paper noted that all of them, except for a widow and her three youngest children, had found employment in the city as manual laborers. The Light encouraged more Jewish refugees to come to Texas, writing “with our mild climate and growing country, they could certainly be helped sooner to secure homes and become self-supporting.”

While this group of Russian immigrants started out as manual laborers, others followed the same path as the earlier German Jewish immigrants, moving into retail trade. Sol Dalkowitz left Lithuania in 1881; after a few months in New York City, he moved south to San Antonio to join his older brother Julius. Both of them started out as peddlers, traveling on foot before acquiring a wagon. They covered the small towns within a 150-mile radius of San Antonio, and would be gone for a few months at a time. After about a year and a half of peddling, they opened a retail store, Dalkowitz Brothers, in San Antonio. Using the contacts they had made as traveling peddlers, Sol and Julius were able to establish a thriving wholesale operation, supplying stores in the small towns of the region.

When Sol Dalkowitz came to San Antonio in 1882, there were only a handful of Orthodox Jews in the city. But as their numbers grew, they began to establish their own religious organizations independent of Beth-El. In 1883, they founded a benevolent society called Gemilath Chasodim (Acts of Loving Kindness), which also held religious services. When they acquired a Torah scroll soon after forming, the society held a dedication ceremony to which they invited Rabbi Lewinthal of Beth-El. While Lewinthal attended the dedication, the local newspaper noted that he did not seem to support the formation of a competing congregation and refused to give the priestly blessing. During the group’s early years, they met for regular minyans at the home of Max Karotkin and at the Odd Fellows Hall for High Holiday services. In 1889, the group established a formal congregation called Agudas Achim (Society of Brothers) with Sol Koenigsberg as their first president. None of the 23 founders, most of whom were merchants, had been founders of Beth-El. This was not a breakaway from the Reform congregation, but rather a distinct group of recent immigrants who wished to worship according to the practices of Orthodox Judaism.

Rabbi Samuel Marks of Beth-El

Rabbi Samuel Marks of Beth-El

In 1890, Agudas Achim bought land for a cemetery and hired their first spiritual leader, Moses Edelhertz, who worked primarily as a shochet (kosher butcher) for the fledgling Orthodox congregation. Moses Sadovsky replaced him 1893. When Agudas Achim held its first High Holiday services at the Knights of Pythias Hall, they drew Orthodox Jews from many of the small towns in the region. For the congregation’s first several years, it met in private homes, rented halls, and the back of members’ stores. Finally, in 1898, Agudas Achim built its first synagogue, dedicating it in a large public ceremony. Rev. Sadovsky led the dedication service, which featured Beth-El’s Rabbi Samuel Marks as the keynote speaker. The Reform rabbi’s prominent involvement reflected a cordial relationship between the two segments of the San Antonio Jewish community. Agudas Achim’s new brick building had a Moorish design with a large domed roof. Befitting an Orthodox congregation, the sanctuary had a separate balcony for women.

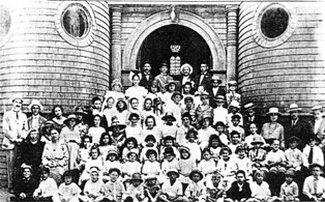

Agudas Achim Religious School, c.1910s

Agudas Achim Religious School, c.1910s

In 1899, Agudas Achim hired Rabbi Solomon Solomon to lead the congregation. By 1907, the congregation had 40 members and $1500 in annual income. Growing numbers of Eastern European Jewish immigrants settling in San Antonio led to a period of growth for the congregation. By 1911, it had 75 members though there were tensions within the congregation over issues of religious ritual. In 1907, the non-Jewish wife of founding member and prominent local attorney Selig Deutschman, died. Deutschman pushed to have her buried in the congregation’s cemetery, against the wishes of Rabbi Solomon and several members. Using his influence within the congregation, she was buried in the Agudas Achim cemetery, though this conflict created rifts that would crack open a few years later. In 1914, in protest of the congregation’s movement away from a strict adherence to Orthodox Judaism, a group broke away to form B’nai Israel. Rabbi Solomon left Agudas Achim to become B’nai Israel’s rabbi the following year.

B’nai Israel did not last very long. A few years before the split at Agudas Achim, a small group of recent immigrants had founded their own Orthodox congregation, Rodfei Sholom (Seekers of Peace), in 1909. By 1916, the two small struggling groups decided to unite, creating Rodfei Sholom B’nai Israel. Later, the name was shortened to just Rodfei Sholom.The new congregation, with about 100 members, quickly bought a house to use as a synagogue. In 1918, they tore it down and built a new synagogue on the lot, which hosted daily morning and evening services and included a mikvah (ritual bath). By the 1910s, San Antonio had a significant community of Orthodox Jews. In 1912, there were two kosher butchers, making kosher meat easy to obtain. By the 1920s, there were several kosher restaurants in San Antonio catering to the Orthodox community.

B’nai Israel did not last very long. A few years before the split at Agudas Achim, a small group of recent immigrants had founded their own Orthodox congregation, Rodfei Sholom (Seekers of Peace), in 1909. By 1916, the two small struggling groups decided to unite, creating Rodfei Sholom B’nai Israel. Later, the name was shortened to just Rodfei Sholom.The new congregation, with about 100 members, quickly bought a house to use as a synagogue. In 1918, they tore it down and built a new synagogue on the lot, which hosted daily morning and evening services and included a mikvah (ritual bath). By the 1910s, San Antonio had a significant community of Orthodox Jews. In 1912, there were two kosher butchers, making kosher meat easy to obtain. By the 1920s, there were several kosher restaurants in San Antonio catering to the Orthodox community.

Sol Dalkowitz

Sol Dalkowitz

Jewish Organizations in San Antonio

Although San Antonio’s Orthodox Jews were divided into two congregations, they came together to educate their children in the community Talmud Torah, chartered in 1912. Called the Hebrew Institute, the school taught Hebrew language and Jewish history to students on weekday afternoons. The school grew out of Agudas Achim, where it initially met. When the synagogue could not accommodate the school’s 200 students, a separate Hebrew Institute building was constructed in 1923 after Alexander Joske gave $10,000 to help build it. For many years, Israel Lewin ran the school, which attracted children from both Agudas Achim and Rodfei Sholom. The building was also used as a meeting place by various Jewish organizations in the city, functioning almost as a Jewish community center. The Institute dissolved after World War II once the congregations established their own Hebrew Schools.

The growing number of immigrants in San Antonio helped inspire women to establish a chapter of the Council of Jewish Women in 1907. Two years later, the group had 120 members. Led by their first president, Anna Hertzberg, the CJW created a night school to teach English and civics to the city’s immigrant population. In the 1920s, the council started a kindergarten for poor children, most of whom were not Jewish. Later, they helped establish the Lighthouse for the Blind and a baby clinic. Initially, most council members were affiliated with Beth-El, the city’s Reform temple. In its first few years, 87% of members were native-born; the rest were immigrants from Germany or France who had spent many years in the U.S. Almost two-thirds of these early members were married, though a significant minority were single, with most still living with their parents. Over time, women from the other congregations became active in the council. Leah Goot, whose husband Max was a charter member of Agudas Achim, led the council’s sewing committee, which made clothes for arriving immigrants at Ellis Island. By 1929, the CJW had over 300 members. After World War II, the council remained a progressive force in San Antonio, pushing for desegregation and establishing an integrated kindergarten in the 1960s. The San Antonio Chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women remains active today.

Although San Antonio’s Orthodox Jews were divided into two congregations, they came together to educate their children in the community Talmud Torah, chartered in 1912. Called the Hebrew Institute, the school taught Hebrew language and Jewish history to students on weekday afternoons. The school grew out of Agudas Achim, where it initially met. When the synagogue could not accommodate the school’s 200 students, a separate Hebrew Institute building was constructed in 1923 after Alexander Joske gave $10,000 to help build it. For many years, Israel Lewin ran the school, which attracted children from both Agudas Achim and Rodfei Sholom. The building was also used as a meeting place by various Jewish organizations in the city, functioning almost as a Jewish community center. The Institute dissolved after World War II once the congregations established their own Hebrew Schools.

The growing number of immigrants in San Antonio helped inspire women to establish a chapter of the Council of Jewish Women in 1907. Two years later, the group had 120 members. Led by their first president, Anna Hertzberg, the CJW created a night school to teach English and civics to the city’s immigrant population. In the 1920s, the council started a kindergarten for poor children, most of whom were not Jewish. Later, they helped establish the Lighthouse for the Blind and a baby clinic. Initially, most council members were affiliated with Beth-El, the city’s Reform temple. In its first few years, 87% of members were native-born; the rest were immigrants from Germany or France who had spent many years in the U.S. Almost two-thirds of these early members were married, though a significant minority were single, with most still living with their parents. Over time, women from the other congregations became active in the council. Leah Goot, whose husband Max was a charter member of Agudas Achim, led the council’s sewing committee, which made clothes for arriving immigrants at Ellis Island. By 1929, the CJW had over 300 members. After World War II, the council remained a progressive force in San Antonio, pushing for desegregation and establishing an integrated kindergarten in the 1960s. The San Antonio Chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women remains active today.

Dr. Sigmund Berg

Dr. Sigmund Berg

Zionism in San Antonio

While council members sought to improve conditions in San Antonio, other Jews worked to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine. In fact, San Antonio was an early Zionist enclave in the state. The city’s first Zionist organization, Mevasereth Zion, was founded in 1897, soon after the First International Zionist Congress was held in Basel, Switzerland. Its leader was Dr. Sigmund Burg, an Austrian-born health officer for the city who had been among the original members of the Jewish Kadimah Society at the University of Vienna, a hotbed of Jewish nationalism. Burg led the way in establishing the statewide Texas Zionist Association in 1905. In 1925, Burg moved to Jerusalem, where he opened a free medical clinic, though he returned to San Antonio four years later.

While council members sought to improve conditions in San Antonio, other Jews worked to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine. In fact, San Antonio was an early Zionist enclave in the state. The city’s first Zionist organization, Mevasereth Zion, was founded in 1897, soon after the First International Zionist Congress was held in Basel, Switzerland. Its leader was Dr. Sigmund Burg, an Austrian-born health officer for the city who had been among the original members of the Jewish Kadimah Society at the University of Vienna, a hotbed of Jewish nationalism. Burg led the way in establishing the statewide Texas Zionist Association in 1905. In 1925, Burg moved to Jerusalem, where he opened a free medical clinic, though he returned to San Antonio four years later.

Leah Goot

Leah Goot

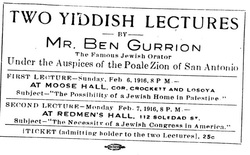

In 1914, Henrietta Szold visited San Antonio and organized a chapter of Hadassah. Though the chapter soon became defunct, it was reorganized when Szold visited again in 1917. Leah Goot served as the chapter’s first president, remaining in the position for 17 years. Hadassah raised money for the Jewish settlement in Palestine and also had a sewing circle that made clothes for Jewish settlers there. Goot had a special sewing room in her house with four sewing machines; local merchants donated the fabric. San Antonio also had an active group of Labor Zionists, who mixed their support for a Jewish homeland with a commitment to socialism. In 1915, after a lecture by noted Zionist and socialist Nachman Syrkin, San Antonio Jews founded a chapter of the Labor Zionist group Poale Zion. The group brought in world Zionist leaders like David Ben-Gurion and Issac Ben Zvi, who lectured to their audiences in Yiddish. In 1926, a chapter of Pioneer Women was established. Until the late 1930s, San Antonio was the only Texas city that had these Labor Zionist organizations, which would attract members from other towns in the state. Religious Zionists established a chapter of Mizrachi in San Antonio in 1929.

Ad for Ben Gurion's 1916 lectures in San Antonio

Ad for Ben Gurion's 1916 lectures in San Antonio

Support for Zionism in San Antonio went beyond these various organizations. In 1915, Agudas Achim voted to assess each member $25 with the money going to support the Zionist cause. Two years later, the congregation passed a resolution in support of the Balfour Declaration. When Britain issued a white paper limiting Jewish immigration to Palestine in 1930, the San Antonio Jewish community swung into action. Fifteen local Jewish organizations formed an emergency committee that held a mass protest meeting at Agudas Achim. San Antonio Mayor C.M. Chambers spoke during the event, as did local community leaders like Leah Goot and Rabbi Ephraim Frisch of Temple Beth-El. During his address, Rabbi Frisch called for the creation of a Jewish refuge in Palestine. While Reform congregations in Houston and Dallas opposed Zionism at the time, Beth-El’s leadership sent a telegram to their congressman and senators protesting Britain’s actions.

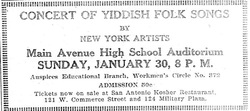

Ad for Yiddish Folk song program sponsored by the San Antonio Workmen's Circle

Ad for Yiddish Folk song program sponsored by the San Antonio Workmen's Circle

Despite this Reform support, San Antonio’s strong Zionist movement derived primarily from the city’s Eastern European Jewish community. For these immigrants, Yiddish was their native language. A desire to preserve this mother tongue and to advance the cause of socialism led a group of San Antonio Jews to establish a branch of the Workmen’s Circle in 1913. The Workmen’s Circle, along with Poale Zion, created a Yiddish Folk Shule in 1925. At the school, children learned the Yiddish language, Jewish history, and current events from a socialist perspective. After a few months, the school’s students held a concert featuring songs, recitations, and theatrical scenes from the work of famous Yiddish writers. Rabbi Abraham Bengis of Agudas Achim attended, and according to a local newspaper account, was amazed that “over 30 children all born and reared on American soil should with such ease…render in the Yiddish language, the language which their parents can understand best.” While the circle was socialist in orientation, holding a public memorial after Socialist Party leader Eugene Debs died in 1926, its members were much more likely to own stores than to be a part of the working class. The Circle worked primarily to preserve the Yiddish language and culture. They would bring in Yiddish theater groups to San Antonio as late as 1947. Although they created a Young Circle League youth auxiliary in the 1930s, the Circle appealed primarily to immigrants, and did not remain active once that generation passed.

Perry Kallison. Photo courtesy of Temple Beth-El

Perry Kallison. Photo courtesy of Temple Beth-El

Jewish Industry and Business

While some San Antonio Jews supported the ideals of socialism, others were industrialists drawn to the city because of its cheap labor. Indeed, Jews played central roles in two of the city’s major labor disputes during the 1930s. Charles Schwartz moved his shirt and dress manufacturing company to San Antonio from Chicago in 1918. In 1934, the International Ladies Garment Worker Union sent in labor organizer Meyer Pearlstein to organize the Hispanic women who worked at Schwartz’s Dorothy Frocks company. In 1936, the company’s 50 workers went out on strike, which resulted in violent clashes on the picket line. Schwartz’s widow, Lily, decided to close the plant and move the company to Dallas, where unions had not yet established a foothold. Julius Seligmann founded the Southern Pecan Shelling Company in 1926, aiming to use cheap Mexican female labor. Seligmann used a contractor system to get around federal rules on wages. In 1937, the company’s 10,000 shellers went out on strike. While the strike was settled in arbitration, Seligmann soon mechanized his operation, reducing his workforce from 10,000 to 800 in the early 1940s. Seligmann sold the company in 1946.

In addition to industry, San Antonio Jews were heavily involved in the city’s retail trade. In the 20th century, a number of the city’s most prominent department stores, including Richbook, Wolff & Marx, Blum’s, Dalkowitz, and Solo Serve, were Jewish-owned. Will Frost got his start working for the Joske Brothers store. In 1917, he left to open a ladies clothing store with his brother Joe. During the 1920s and 30s, they expanded the business into the finest department store in the city. Frost Brothers installed air conditioning in their four-story building, one of the first stores to do so. The Frost Brothers store employed many Jews as both salespeople and managers. When the brothers died in the 1940s, the store was sold to Gilbert and Sylvan Lang, who expanded the business to locations across the state. In 1970, the chain was sold to Manhattan Industries.

Perhaps the most uniquely Texan Jewish-owned business in San Antonio was the saddle shop opened by Nathan Kallison in 1899. The family later owned two different stores: Kallison’s Western Wear and Kallison’s Farm and Ranch Store. Nathan’s sons Morris and Perry later took over the businesses. Perry also broadcasted a radio show called “Cow Country News” for over 40 years, using it to promote the store. During his daily 15-minute show, Kallison provided farm and ranch-themed news to his listeners across west Texas. Kallison, along with Joe and Harry Freeman, helped lead the charge to get a city coliseum built, convincing San Antonio voters to approve the bond money arguing that it would be able to host an annual livestock show and rodeo. In addition to his stores and radio broadcasts, Kallison also owned a ranch and raised his own cattle.

While some San Antonio Jews supported the ideals of socialism, others were industrialists drawn to the city because of its cheap labor. Indeed, Jews played central roles in two of the city’s major labor disputes during the 1930s. Charles Schwartz moved his shirt and dress manufacturing company to San Antonio from Chicago in 1918. In 1934, the International Ladies Garment Worker Union sent in labor organizer Meyer Pearlstein to organize the Hispanic women who worked at Schwartz’s Dorothy Frocks company. In 1936, the company’s 50 workers went out on strike, which resulted in violent clashes on the picket line. Schwartz’s widow, Lily, decided to close the plant and move the company to Dallas, where unions had not yet established a foothold. Julius Seligmann founded the Southern Pecan Shelling Company in 1926, aiming to use cheap Mexican female labor. Seligmann used a contractor system to get around federal rules on wages. In 1937, the company’s 10,000 shellers went out on strike. While the strike was settled in arbitration, Seligmann soon mechanized his operation, reducing his workforce from 10,000 to 800 in the early 1940s. Seligmann sold the company in 1946.

In addition to industry, San Antonio Jews were heavily involved in the city’s retail trade. In the 20th century, a number of the city’s most prominent department stores, including Richbook, Wolff & Marx, Blum’s, Dalkowitz, and Solo Serve, were Jewish-owned. Will Frost got his start working for the Joske Brothers store. In 1917, he left to open a ladies clothing store with his brother Joe. During the 1920s and 30s, they expanded the business into the finest department store in the city. Frost Brothers installed air conditioning in their four-story building, one of the first stores to do so. The Frost Brothers store employed many Jews as both salespeople and managers. When the brothers died in the 1940s, the store was sold to Gilbert and Sylvan Lang, who expanded the business to locations across the state. In 1970, the chain was sold to Manhattan Industries.

Perhaps the most uniquely Texan Jewish-owned business in San Antonio was the saddle shop opened by Nathan Kallison in 1899. The family later owned two different stores: Kallison’s Western Wear and Kallison’s Farm and Ranch Store. Nathan’s sons Morris and Perry later took over the businesses. Perry also broadcasted a radio show called “Cow Country News” for over 40 years, using it to promote the store. During his daily 15-minute show, Kallison provided farm and ranch-themed news to his listeners across west Texas. Kallison, along with Joe and Harry Freeman, helped lead the charge to get a city coliseum built, convincing San Antonio voters to approve the bond money arguing that it would be able to host an annual livestock show and rodeo. In addition to his stores and radio broadcasts, Kallison also owned a ranch and raised his own cattle.

Anna Hertzberg

Anna Hertzberg

Civic Engagement

In many cases, San Antonio’s Jewish merchants became civic leaders. Nathan Washer moved to San Antonio from Fort Worth in 1899 to open a branch of the men’s clothing store he owned with his brother. An extremely active Mason, Washer served as state-wide Grand Master of the Texas Masons in 1901. Later, the San Antonio Masonic Lodge was named for Washer, who also served as president of the local chamber of commerce, a position he had earlier held in Fort Worth as well. Washer served on the San Antonio school board, leading the effort in 1922 for a $2 million bond measure that resulted in six new schools being built. Texas Governor Dan Moody appointed Washer to the state board of education in 1927; Washer served as president of the board until his death in 1935. Washer also spent 20 years on the San Antonio Public Library Board and helped establish the local symphony orchestra society in 1915.

In 1914, the San Antonio Express ran a special section on the local Jewish community. With a headline that read, “Charity, Works of Peace, and Prosperity Distinguish Jewish people of San Antonio,” the main article stressed the civic and charitable contributions Jews had made to the city. No one fits this description better than Anna Hertzberg. The wife of a successful jewelry merchant, Hertzberg moved to San Antonio after marrying in 1882. A lover of music, Hertzberg organized the Tuesday Night Music Club, a women’s musical appreciation group that met in her home for 30 years before it moved to a house it had purchased next door. Hertzberg was also one of the founders of the San Antonio Symphony. In addition to music, Hertzberg’s other passion was education. In 1915, she was elected to the San Antonio school board at a time when women didn’t yet have the right to vote. During the election, both competing sides included Hertzberg on their ticket, attesting to the esteem in which she was held by the community. As president of the local Council of Jewish Women, Hertzberg helped create the night school for newly arrived immigrants. Hertzberg was also active in various women’s clubs, serving as president of the San Antonio and later the Texas Federation of Women’s Clubs.

In many cases, San Antonio’s Jewish merchants became civic leaders. Nathan Washer moved to San Antonio from Fort Worth in 1899 to open a branch of the men’s clothing store he owned with his brother. An extremely active Mason, Washer served as state-wide Grand Master of the Texas Masons in 1901. Later, the San Antonio Masonic Lodge was named for Washer, who also served as president of the local chamber of commerce, a position he had earlier held in Fort Worth as well. Washer served on the San Antonio school board, leading the effort in 1922 for a $2 million bond measure that resulted in six new schools being built. Texas Governor Dan Moody appointed Washer to the state board of education in 1927; Washer served as president of the board until his death in 1935. Washer also spent 20 years on the San Antonio Public Library Board and helped establish the local symphony orchestra society in 1915.

In 1914, the San Antonio Express ran a special section on the local Jewish community. With a headline that read, “Charity, Works of Peace, and Prosperity Distinguish Jewish people of San Antonio,” the main article stressed the civic and charitable contributions Jews had made to the city. No one fits this description better than Anna Hertzberg. The wife of a successful jewelry merchant, Hertzberg moved to San Antonio after marrying in 1882. A lover of music, Hertzberg organized the Tuesday Night Music Club, a women’s musical appreciation group that met in her home for 30 years before it moved to a house it had purchased next door. Hertzberg was also one of the founders of the San Antonio Symphony. In addition to music, Hertzberg’s other passion was education. In 1915, she was elected to the San Antonio school board at a time when women didn’t yet have the right to vote. During the election, both competing sides included Hertzberg on their ticket, attesting to the esteem in which she was held by the community. As president of the local Council of Jewish Women, Hertzberg helped create the night school for newly arrived immigrants. Hertzberg was also active in various women’s clubs, serving as president of the San Antonio and later the Texas Federation of Women’s Clubs.

Beth-El's current home, built in 1927.

Beth-El's current home, built in 1927. Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler.

Congregations in the Mid-20th Century

By 1937, an estimated 6,900 Jews lived in the Alamo City, while 20 years earlier there had been just 3,000. World War II would have a significant impact on the city, as its population grew 61% during the 1940s. Fort Sam Houston and multiple Air Force bases in the area provided a solid economic base for the city in the post-war years. The Jewish community flourished as well, growing to 9,000 people by 1984.

This community growth had a significant impact on the city’s three Jewish congregations. By 1924, Beth-El, with over 300 member families, had outgrown its temple, and began to raise money for a new building. Dedicated in 1927, Beth El’s new synagogue could seat over 1200 people in its sanctuary. The attached Community Center building had 11 classrooms, a kitchen, dining room, and auditorium. In 1938, they hired David Jacobson as an associate rabbi; Jacobson became Beth-El’s senior rabbi when Rabbi Frisch retired in 1942. Under Rabbi Jacobson’s leadership, Beth-El moved away from classical Reform Judaism, embracing such traditions as Hebrew instruction and the bar mitzvah. Beth-El grew significantly during the war years, reaching 599 members in 1945. As a consequence, Beth-El had to expand their building in 1946, adding a new chapel, auditorium, and social hall. By the time of Rabbi Jacobson’s retirement in 1976, Beth-El had 853 families. Rabbi Samuel Stahl took the reins next as Beth-El’s senior rabbi, leading the Reform congregation for the next quarter century. The city’s only Reform congregation had well over 1100 families by 1995.

Agudas Achim experienced similar growth. In 1918, they bought land for a new larger synagogue; after their building flooded in 1921, they moved quickly to construct a new synagogue on Main and Quincy Streets, which was completed in 1923. By the end of the decade, Agudas Achim had already outgrown its new building. Under the leadership of Rabbi Gershon Feigenbaum, who came in 1919, Agudas Achim moved away from strict Orthodoxy during the 1920s. Rabbi Feigenbaum instituted Friday night services, the confirmation ceremony, and a mixed-gender choir during his short tenure. By 1948, Agudas Achim officially affiliated with the Conservative movement. After some economic hardships during the early years of the Great Depression, during which the congregation could not afford a full-time rabbi, Agudas Achim enjoyed greater stability in rabbinic leadership. Rabbi David Tamarkin led the congregation from 1933 to 1947. Sidney Guthman replaced him, serving until 1956. From 1958 to 1980, Rabbi Amram Prero served as Agudas Achim’s spiritual leader.

By 1937, an estimated 6,900 Jews lived in the Alamo City, while 20 years earlier there had been just 3,000. World War II would have a significant impact on the city, as its population grew 61% during the 1940s. Fort Sam Houston and multiple Air Force bases in the area provided a solid economic base for the city in the post-war years. The Jewish community flourished as well, growing to 9,000 people by 1984.

This community growth had a significant impact on the city’s three Jewish congregations. By 1924, Beth-El, with over 300 member families, had outgrown its temple, and began to raise money for a new building. Dedicated in 1927, Beth El’s new synagogue could seat over 1200 people in its sanctuary. The attached Community Center building had 11 classrooms, a kitchen, dining room, and auditorium. In 1938, they hired David Jacobson as an associate rabbi; Jacobson became Beth-El’s senior rabbi when Rabbi Frisch retired in 1942. Under Rabbi Jacobson’s leadership, Beth-El moved away from classical Reform Judaism, embracing such traditions as Hebrew instruction and the bar mitzvah. Beth-El grew significantly during the war years, reaching 599 members in 1945. As a consequence, Beth-El had to expand their building in 1946, adding a new chapel, auditorium, and social hall. By the time of Rabbi Jacobson’s retirement in 1976, Beth-El had 853 families. Rabbi Samuel Stahl took the reins next as Beth-El’s senior rabbi, leading the Reform congregation for the next quarter century. The city’s only Reform congregation had well over 1100 families by 1995.

Agudas Achim experienced similar growth. In 1918, they bought land for a new larger synagogue; after their building flooded in 1921, they moved quickly to construct a new synagogue on Main and Quincy Streets, which was completed in 1923. By the end of the decade, Agudas Achim had already outgrown its new building. Under the leadership of Rabbi Gershon Feigenbaum, who came in 1919, Agudas Achim moved away from strict Orthodoxy during the 1920s. Rabbi Feigenbaum instituted Friday night services, the confirmation ceremony, and a mixed-gender choir during his short tenure. By 1948, Agudas Achim officially affiliated with the Conservative movement. After some economic hardships during the early years of the Great Depression, during which the congregation could not afford a full-time rabbi, Agudas Achim enjoyed greater stability in rabbinic leadership. Rabbi David Tamarkin led the congregation from 1933 to 1947. Sidney Guthman replaced him, serving until 1956. From 1958 to 1980, Rabbi Amram Prero served as Agudas Achim’s spiritual leader.

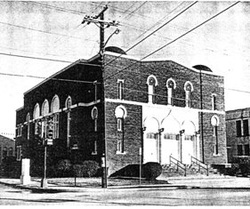

Agudas Achim's 2nd synagogue, built in 1923

Agudas Achim's 2nd synagogue, built in 1923

The pews and classrooms at Agudas Achim swelled during the years after World War II. By 1952, the congregation was looking to build a new larger synagogue to accommodate the growth. In 1954 they dedicated a new synagogue on Donaldson Avenue. In the mid-1960s, Agudas Achim had about 680 member families. By the end of the 1980s, most of its members had moved out to the northwestern part of the city. Agudas Achim decided to follow its members, building a new synagogue on Huebner Road in 1992.

Being located close to its members was even more important for Rodfei Sholom, since its Shabbat-observant congregants had to walk to synagogue on Saturdays. By 1940, many of the Orthodox congregation’s members were moving away from the synagogue’s Wyoming Street neighborhood. In response, Rodfei Sholom bought a two-story house at Laurel and Ogden Streets, holding services in the remodeled ground floor. In 1950, they tore the house down to build a synagogue on the property. While their new building was being constructed, Rodfei Sholom, the smallest of San Antonio’s three congregations, met for daily services in a room over the garage at the Laurel Hotel. Finally, they dedicated their new synagogue in 1951. Due to an increasing number of children, the congregation added a new education wing and auditorium in 1954. In 1959, Rodfei Sholom celebrated its 50th anniversary with a gala banquet at which then- Senator Lyndon Johnson was the keynote speaker.

Being located close to its members was even more important for Rodfei Sholom, since its Shabbat-observant congregants had to walk to synagogue on Saturdays. By 1940, many of the Orthodox congregation’s members were moving away from the synagogue’s Wyoming Street neighborhood. In response, Rodfei Sholom bought a two-story house at Laurel and Ogden Streets, holding services in the remodeled ground floor. In 1950, they tore the house down to build a synagogue on the property. While their new building was being constructed, Rodfei Sholom, the smallest of San Antonio’s three congregations, met for daily services in a room over the garage at the Laurel Hotel. Finally, they dedicated their new synagogue in 1951. Due to an increasing number of children, the congregation added a new education wing and auditorium in 1954. In 1959, Rodfei Sholom celebrated its 50th anniversary with a gala banquet at which then- Senator Lyndon Johnson was the keynote speaker.

Senator Lyndon Johnson celebrating

Senator Lyndon Johnson celebrating Rodfei Sholom's 50th anniversary in 1959

By the 1960s, Rodfei Sholom was shrinking as many of the children and grandchildren of the congregation’s immigrant founders were moving away from Orthodox Judaism. By 1970, only 70 families still belonged to San Antonio’s only Orthodox congregation. That same year, Rodfei Sholom hired Rabbi Aryeh Scheinberg, who has presided over a renaissance during his four-decade tenure. By the late 1970s, the neighborhood around the synagogue had deteriorated as many members had moved to the northwest part of the city. In 1989, Rodfei Sholom bought land on Northwest Military Highway, dedicating a new synagogue there two years later. Still an Orthodox congregation, Rodfei Sholom included a mikvah and a mechitza (a barrier separating men and women in the sanctuary) in its new building. In 2006, Rodfei Sholom had grown to over 300 families, necessitating an expansion to their synagogue. Today, the synagogue is surrounded by Shalom Place, a neighborhood subdivision where many members have bought homes so they can easily walk to Rodfei Sholom on Shabbat. Chabad, founded by Rabbi Chaim Block in 1985 boasts a staff three rabbis and recently opened a satellite center for the students of the University of Texas San Antonio. Today, they have a vibrant community and synagogue, preschool, summer camp, mikvah, and many other significant institutions.

Rodfei Sholom remains an Orthodox congregation,

Rodfei Sholom remains an Orthodox congregation, with a mechitza in its sanctuary

20th Century Civic and Political Engagement

During the second half of the 20th century, San Antonio Jews remained active in the city’s civic life. Some helped San Antonio to change during the Civil Rights era. Rabbi David Jacobson of Beth-El worked with the bishops of the Catholic and Episcopal Dioceses to integrate the city peacefully. Jacobson received the Martin Luther King Distinguished Achievement Award for his efforts. Local businessman Bill Sinkin also worked to dismantle segregation in San Antonio. In the early 1960s, Sinkin co-founded the Urban Coalition to create dialogue between whites, blacks, and Hispanics in the city. Through the coalition, Sinkin convinced the local Fiesta Parade to allow an African American band to take part and worked with the local police department to reduce brutality against suspects of color. Sinkin also helped integrate San Antonio businesses, sitting in at the local Kress Department store with an African American minister friend until he was served at the lunch counter. Later, Sinkin served as head of the city’s Public Housing Authority.

During the second half of the 20th century, San Antonio Jews remained active in the city’s civic life. Some helped San Antonio to change during the Civil Rights era. Rabbi David Jacobson of Beth-El worked with the bishops of the Catholic and Episcopal Dioceses to integrate the city peacefully. Jacobson received the Martin Luther King Distinguished Achievement Award for his efforts. Local businessman Bill Sinkin also worked to dismantle segregation in San Antonio. In the early 1960s, Sinkin co-founded the Urban Coalition to create dialogue between whites, blacks, and Hispanics in the city. Through the coalition, Sinkin convinced the local Fiesta Parade to allow an African American band to take part and worked with the local police department to reduce brutality against suspects of color. Sinkin also helped integrate San Antonio businesses, sitting in at the local Kress Department store with an African American minister friend until he was served at the lunch counter. Later, Sinkin served as head of the city’s Public Housing Authority.

Rabbi David Jacobson.

Rabbi David Jacobson.

In recent years, San Antonio Jews have been involved in state politics. Rose Spector, who was born and raised in San Antonio, became a lawyer and local judge. In 1974, she was elected County Judge, the first woman to serve in that position in Bexar County. Six years later, she was elected as district judge. In 1992, Spector ran successfully for the Texas Supreme Court, becoming the first and so far only Jew to be elected to statewide office in Texas. Spector, a Democrat, was a progressive voice on the increasingly conservative court. In 1998, she lost her re-election bid in a Republican sweep of statewide offices. The rising dominance of the Texas Republican Party has been very beneficial to Joe Straus, who was elected to the State House of Representatives from San Antonio in 2005. In 2009, Straus, a relatively moderate Republican, emerged as a compromise candidate and was selected as Speaker of the Texas House. When he sought re-election to the post, two years later, his Jewishness briefly became an issue as some Texas conservatives called for a Christian speaker. Despite this, Straus was easily re-elected by his colleagues in 2011.

The Jewish Community in San Antonio Today

Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives

Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives Joe Straus

Today, the San Antonio Jewish community remains strong. With an estimated 11,200 Jews in 2007, the community has remained steady, though it has not grown. In addition to Beth-El, Agudas Achim, and Rodfei Sholom, new Jewish congregations have formed in recent years. Beth Am, the city’s Reconstructionist congregation, was founded in 1987. The Reform Temple Chai was organized in 2005, while the unaffiliated Congregation Israel was established the following year.

The Jewish community enjoys the resources of a big city, including: a Jewish Federation, founded in 1922; a Jewish Community Center, established in 1935; a Jewish Family Service; and a Jewish community day school, founded in 1973. While San Antonio is no longer the state’s third largest Jewish community, having been surpassed by nearby Austin in recent years, it remains a vibrant and historic community.

The Jewish community enjoys the resources of a big city, including: a Jewish Federation, founded in 1922; a Jewish Community Center, established in 1935; a Jewish Family Service; and a Jewish community day school, founded in 1973. While San Antonio is no longer the state’s third largest Jewish community, having been surpassed by nearby Austin in recent years, it remains a vibrant and historic community.