Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Wichita Falls, Texas

Wichita Falls: Historical Overview

The few families who lived in remote Wichita County, just south of the Oklahoma border, lobbied hard to bring the Fort Worth and Denver Railroad to the area, offering major property concessions along the right-of-way. In 1882, their dream was achieved, as the train tracks helped create a land boom and sparked economic development in the area. In 1889, the settlement was incorporated as Wichita Falls; a year later 2,000 people lived in the town. By the turn of the century, several more railroad lines had been built through Wichita Falls, which became a regional transportation and supply hub. Jews have been part of Wichita Falls since the late 19th century.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Wichita Falls

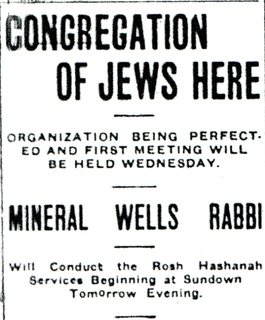

This 1913 local newspaper article

This 1913 local newspaper article described the first effort to form a congregation.

Early Settlers

Perhaps the first Jews to settle in Wichita Falls were Albert and Rebecca Zundelowitz, who came to town in the late 1880s to open a clothing store. Both were born in Russia; Albert immigrated to the United States in 1865, with Rebecca following four years later. They married in 1873, and later lived in Iowa before moving to Wichita Falls. Albert became one of the city’s most prominent businessmen, helping to found City National Bank. By 1910, he had retired and was living on his investments. He was also a rancher, owning property on the West Texas plains. Zundelowitz was very civically minded, serving as an alderman in the 1890s and donating $30,000 to help build a local public school, which was named in his honor. In 1924, the local newspaper recognized Albert and Rebecca as “pioneer residents” of Wichita Falls who had lived in the town since its earliest days

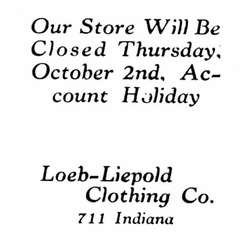

Following the arrival of Albert and Rebecca Zundelowitz, a handful of other Jews moved to Wichita Falls in the late 19th century. Alex Kahn moved to town around 1890 to work for Zundelowitz’s store. Kahn later opened his own clothing store in town. Henry Kahn owned a furniture store in the 1890s while Max Marcus was a dry good salesman in Wichita Falls by 1890. Gene Liepold, a German native, came to Wichita Falls in 1909 and opened the Loeb-Liepold clothing store, which he managed for 45 years. Liepold became a beloved figure in town, carrying jelly beans in his pockets so he could give them out to children in town. A big sports fan, Liepold owned a local semi-pro baseball team and led parades and pep rallies for the local high school football team.

By 1910, there were only a handful of Jewish-owned stores in Wichita Falls, and the Jewish community was still fairly small. Things would change once oil was discovered in the area in 1911. A major oil strike in 1918 transformed Wichita Falls into a boomtown. The city grew from about 8,000 residents in 1910 to over 40,000 a decade later. By 1920, the city had nine oil refineries and 47 factories. Wichita Falls’ emergence as an oil center attracted growing numbers of Jews to the city, most of whom opened retail stores. Louis Pink moved to Wichita Falls from Indianapolis in the 1910s to open the Palace Drug Store. Several other Jewish families moved to town as well, as the ranks of Jewish-owned businesses swelled. By 1927, an estimated 505 Jews lived in Wichita Falls.

Perhaps the first Jews to settle in Wichita Falls were Albert and Rebecca Zundelowitz, who came to town in the late 1880s to open a clothing store. Both were born in Russia; Albert immigrated to the United States in 1865, with Rebecca following four years later. They married in 1873, and later lived in Iowa before moving to Wichita Falls. Albert became one of the city’s most prominent businessmen, helping to found City National Bank. By 1910, he had retired and was living on his investments. He was also a rancher, owning property on the West Texas plains. Zundelowitz was very civically minded, serving as an alderman in the 1890s and donating $30,000 to help build a local public school, which was named in his honor. In 1924, the local newspaper recognized Albert and Rebecca as “pioneer residents” of Wichita Falls who had lived in the town since its earliest days

Following the arrival of Albert and Rebecca Zundelowitz, a handful of other Jews moved to Wichita Falls in the late 19th century. Alex Kahn moved to town around 1890 to work for Zundelowitz’s store. Kahn later opened his own clothing store in town. Henry Kahn owned a furniture store in the 1890s while Max Marcus was a dry good salesman in Wichita Falls by 1890. Gene Liepold, a German native, came to Wichita Falls in 1909 and opened the Loeb-Liepold clothing store, which he managed for 45 years. Liepold became a beloved figure in town, carrying jelly beans in his pockets so he could give them out to children in town. A big sports fan, Liepold owned a local semi-pro baseball team and led parades and pep rallies for the local high school football team.

By 1910, there were only a handful of Jewish-owned stores in Wichita Falls, and the Jewish community was still fairly small. Things would change once oil was discovered in the area in 1911. A major oil strike in 1918 transformed Wichita Falls into a boomtown. The city grew from about 8,000 residents in 1910 to over 40,000 a decade later. By 1920, the city had nine oil refineries and 47 factories. Wichita Falls’ emergence as an oil center attracted growing numbers of Jews to the city, most of whom opened retail stores. Louis Pink moved to Wichita Falls from Indianapolis in the 1910s to open the Palace Drug Store. Several other Jewish families moved to town as well, as the ranks of Jewish-owned businesses swelled. By 1927, an estimated 505 Jews lived in Wichita Falls.

Notice from the Loeb-Liepold store

Notice from the Loeb-Liepold store printed in local newspaper in 1913.

Organized Jewish Life in Wichita Falls

As the number of Jews grew, they slowly began to organize communal institutions. In 1910, the Wichita Daily Times noted that “several local establishments conducted by Jews” would be closed for Rosh Hashanah, although there was no mention of services being held in the city. In 1913, the newspaper reported that Jews had founded the city’s first Jewish congregation and would be holding religious services at Moose Hall. A Rabbi Hoffman of Mineral Wells led the services, which were held for the traditional two days. They brought in a Torah from Dallas for the occasion. Leonard Art, a native of Holland, was the group’s leader. They did not plan to hold regular Shabbat services during the first year, yet still hoped to buy land for a synagogue as soon as they could. The paper noted, “there is now a considerable number of citizens of the Jewish faith in Wichita Falls and it is hoped to organize a flourishing congregation.”

Apparently this early effort did not maintain its momentum since two years later in 1915 the Wichita Daily Times reported that local Jews had recently organized a congregation called Temple Israel. Rabbi George Fox of Temple Beth-El in Fort Worth came to lead services that were held in the building owned by J.L. Art, Leonard’s son. That same year, Wichita Falls Jews organized a chapter of B’nai B’rith with 25 charter members.

By the late 1910s, after the oil boom, the Jewish community developed rather quickly. By 1917, local women had founded a Hebrew Ladies Aid Society, which raised money for Jewish war sufferers. The following year, a chapter of the Council of Jewish Women was established, with Frieda Pink as its first president. Around the same time, Frieda and her husband Louis Pink organized a religious school for Temple Israel. The congregation was meeting at First Presbyterian Church for Friday night services at the time. In 1919, Temple Israel was formally chartered. In April of that year, the congregation purchased land and began to raise money for a house of worship. In September, the congregation announced plans to hire a full-time rabbi and build a synagogue. Temple Israel quickly achieved these goals, hiring Rabbi David Goldberg in December. By May, 1920, Temple Israel had completed its synagogue, which hosted the congregation’s first-ever confirmation ceremony that month. The new temple was not formally dedicated until January, 1922. Over the dedication weekend, Rabbis David Lefkowitz of Dallas, Martin Zielonka of El Paso, and Maurice Faber of Tyler all gave addresses. Temple Israel was Reform, joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in the early 1920s. By 1925, the congregation had 40 contributing members. When Frieda Pink died in 1921, Temple Israel bought land for a Jewish cemetery.

Not all Wichita Falls Jews supported Reform Judaism. By 1917, a group of Orthodox Jews had organized at the home of B. Catch and began to pray together. In 1920, the group was formally chartered as House of Jacob, with D. Capland as its first president. In its early years, House of Jacob held High Holiday services in various office buildings downtown. Soon, they began to build a synagogue on land selected by Albert Zundelowitz, who supported the Orthodox congregation even though he belonged to Temple Israel. Located on Lamar Street and costing only $6000, this modest synagogue served the 44 families that belonged to House of Jacob when the building was dedicated in 1924.

Soon after forming, House of Jacob was able to hire a chazzan and shochet to lead services and provide kosher meat for members. Reverends Joffe and Israel each served the congregation briefly in its early years. In 1922, House of Jacob hired Aaron Rabinowitz, who spent over 20 years as House of Jacob’s spiritual leader and shochet. The congregation was Orthodox initially, though by 1934 it was only holding Shabbat services on Friday nights, rather than the traditional Saturday mornings since so many members had to keep their stores open on the Sabbath. Despite this compromise to traditional practice, the congregation remained Orthodox, even adding a mikvah to the building later on. They did not insist on their own Orthodox burial ground, and members of House of Jacob were buried in the Temple Israel cemetery. Later, the two congregations created the Hebrew Rest Cemetery Corporation which oversaw the cemetery for the entire Wichita Falls Jewish community.

As the number of Jews grew, they slowly began to organize communal institutions. In 1910, the Wichita Daily Times noted that “several local establishments conducted by Jews” would be closed for Rosh Hashanah, although there was no mention of services being held in the city. In 1913, the newspaper reported that Jews had founded the city’s first Jewish congregation and would be holding religious services at Moose Hall. A Rabbi Hoffman of Mineral Wells led the services, which were held for the traditional two days. They brought in a Torah from Dallas for the occasion. Leonard Art, a native of Holland, was the group’s leader. They did not plan to hold regular Shabbat services during the first year, yet still hoped to buy land for a synagogue as soon as they could. The paper noted, “there is now a considerable number of citizens of the Jewish faith in Wichita Falls and it is hoped to organize a flourishing congregation.”

Apparently this early effort did not maintain its momentum since two years later in 1915 the Wichita Daily Times reported that local Jews had recently organized a congregation called Temple Israel. Rabbi George Fox of Temple Beth-El in Fort Worth came to lead services that were held in the building owned by J.L. Art, Leonard’s son. That same year, Wichita Falls Jews organized a chapter of B’nai B’rith with 25 charter members.

By the late 1910s, after the oil boom, the Jewish community developed rather quickly. By 1917, local women had founded a Hebrew Ladies Aid Society, which raised money for Jewish war sufferers. The following year, a chapter of the Council of Jewish Women was established, with Frieda Pink as its first president. Around the same time, Frieda and her husband Louis Pink organized a religious school for Temple Israel. The congregation was meeting at First Presbyterian Church for Friday night services at the time. In 1919, Temple Israel was formally chartered. In April of that year, the congregation purchased land and began to raise money for a house of worship. In September, the congregation announced plans to hire a full-time rabbi and build a synagogue. Temple Israel quickly achieved these goals, hiring Rabbi David Goldberg in December. By May, 1920, Temple Israel had completed its synagogue, which hosted the congregation’s first-ever confirmation ceremony that month. The new temple was not formally dedicated until January, 1922. Over the dedication weekend, Rabbis David Lefkowitz of Dallas, Martin Zielonka of El Paso, and Maurice Faber of Tyler all gave addresses. Temple Israel was Reform, joining the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in the early 1920s. By 1925, the congregation had 40 contributing members. When Frieda Pink died in 1921, Temple Israel bought land for a Jewish cemetery.

Not all Wichita Falls Jews supported Reform Judaism. By 1917, a group of Orthodox Jews had organized at the home of B. Catch and began to pray together. In 1920, the group was formally chartered as House of Jacob, with D. Capland as its first president. In its early years, House of Jacob held High Holiday services in various office buildings downtown. Soon, they began to build a synagogue on land selected by Albert Zundelowitz, who supported the Orthodox congregation even though he belonged to Temple Israel. Located on Lamar Street and costing only $6000, this modest synagogue served the 44 families that belonged to House of Jacob when the building was dedicated in 1924.

Soon after forming, House of Jacob was able to hire a chazzan and shochet to lead services and provide kosher meat for members. Reverends Joffe and Israel each served the congregation briefly in its early years. In 1922, House of Jacob hired Aaron Rabinowitz, who spent over 20 years as House of Jacob’s spiritual leader and shochet. The congregation was Orthodox initially, though by 1934 it was only holding Shabbat services on Friday nights, rather than the traditional Saturday mornings since so many members had to keep their stores open on the Sabbath. Despite this compromise to traditional practice, the congregation remained Orthodox, even adding a mikvah to the building later on. They did not insist on their own Orthodox burial ground, and members of House of Jacob were buried in the Temple Israel cemetery. Later, the two congregations created the Hebrew Rest Cemetery Corporation which oversaw the cemetery for the entire Wichita Falls Jewish community.

Temple Israel's synagogue

Temple Israel's synagogue

Although Temple Israel and House of Jacob were chartered only one year apart, their members were somewhat different. Of 17 officers, board members, and building committee members of Temple Israel in 1920, over half were born in the United States. Several were native Texans. Of the nine members on House of Jacob’s building committee, all but one were foreign-born. Each of the immigrant members from House of Jacob came from Russia or Poland. Interestingly, all of the foreign-born leaders of Temple Israel also came from Russia or Poland; none were German Jews. Members of both congregations were also involved in similar economic pursuits. Each of the House of Jacob leaders owned a business, mostly retail stores. The only exceptions were one peddler and someone who owned a wholesale oil well supply company. Of the Temple Israel members who had an occupation listed in the 1920 census, all but one owned a business. Most all of these were retail stores as well, except for two who owned an ice manufacturing company. Some Wichita Falls Jews, like Sam Kruger, belonged to both congregations.

With the Wichita Falls Jewish community divided into two congregations, neither was very large. Temple Israel never grew much past the 40 member families it had in 1925. Despite its small size, the Reform congregation was able to hire full-time rabbis in its early years. Rabbi David Goldberg led Temple Israel from 1920 to 1923. He was followed by Samuel Phillips in 1925, though he only stayed two years. S.J. Schwab replaced him in 1927, but left in the early 1930s. Not until 1936 did Temple Israel hire another full-time rabbi, Benjamin Kelson. Rabbi Kelson was replaced by Leo Lichtenberg in 1941, who left in 1943 to serve as a military chaplain. After Rabbi Lichtenberg left, Temple Israel never again had a full-time rabbi. During the years in which they did not have a spiritual leader, Temple Israel would bring in student rabbis from Hebrew Union College or Dr. Hyman Ettlinger, a math professor at the University of Texas, to lead High Holiday services. Rabbi David Lefkowitz of Temple Emanu-El in Dallas would come in to lead confirmation services or officiate at life cycle events. Paul Goldstucker, who had studied to be a rabbi at HUC, often led services as well. Louis Pink spent many years as president at Temple Israel, and was even named president for life in the 1930s.

With the Wichita Falls Jewish community divided into two congregations, neither was very large. Temple Israel never grew much past the 40 member families it had in 1925. Despite its small size, the Reform congregation was able to hire full-time rabbis in its early years. Rabbi David Goldberg led Temple Israel from 1920 to 1923. He was followed by Samuel Phillips in 1925, though he only stayed two years. S.J. Schwab replaced him in 1927, but left in the early 1930s. Not until 1936 did Temple Israel hire another full-time rabbi, Benjamin Kelson. Rabbi Kelson was replaced by Leo Lichtenberg in 1941, who left in 1943 to serve as a military chaplain. After Rabbi Lichtenberg left, Temple Israel never again had a full-time rabbi. During the years in which they did not have a spiritual leader, Temple Israel would bring in student rabbis from Hebrew Union College or Dr. Hyman Ettlinger, a math professor at the University of Texas, to lead High Holiday services. Rabbi David Lefkowitz of Temple Emanu-El in Dallas would come in to lead confirmation services or officiate at life cycle events. Paul Goldstucker, who had studied to be a rabbi at HUC, often led services as well. Louis Pink spent many years as president at Temple Israel, and was even named president for life in the 1930s.

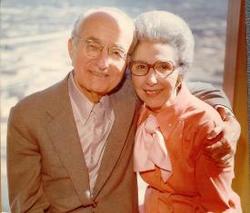

Morris Zale & his wife Edna.

Morris Zale & his wife Edna. Photo courtesy of the M.B. & Edna Zale Foundation.

Jewish Businesses in Wichita Falls

The members of both congregations continued to be concentrated in retail trade. In 1939, numerous Jewish-owned stores were located in downtown Wichita Falls. Such stores included: The Fair, a clothing store owned by Julius and Melvin Augustus, The Hub, a clothing store owned by Sol Lasky, Levine’s Department Store, opened by Morris and William Levine in 1934, which later grew into a regional chain of 150 stores, Baum’s Drug Store, owned by Marie and Chess Baum, the Popular Furniture Store, owned by Leo Schusterman, a used clothing store owned Fannie Meyer, and many others. Jews were also involved in the jewelry business in Wichita Falls. Joseph Art owned a jewelry store for many years, becoming what the local newspaper described as “one of Wichita Falls’ best-known citizens.” He was known for helping out soldiers stationed at nearby Sheppard Field, making loans to them that he never expected to be repaid. Sam Kruger opened a jewelry store in 1912, which remained in business for well over half a century; his nephew Max Kruger ran the store into the 1980s. Max became involved in local politics, serving as mayor of Wichita Falls from 1972 to 1975.

Perhaps the best known jewelry store in America got its start in Wichita Falls. Morris Zale first settled in New York after coming to the U.S. from Russia. A few years later he moved to Texas to be with his uncle, Sam Kruger, who owned a jewelry business. In 1924, with help from his uncle, Morris opened a jewelry store in Wichita Falls, offering easy credit terms and no down payment to his customers. From this modest start, the Zale Jewelry chain of stores grew, bringing jewelry to the masses and transforming an industry that had previously catered to the economic elite. At its peak, the Zale Jewelry Corporation employed 20,000 people. Although Morris moved the operation to Dallas in 1946, the foundation he created has been very philanthropic in the city where the business started. When Morris Zale died in 1995, his foundation donated $400,000 to help build a family health center in Wichita Falls.

The members of both congregations continued to be concentrated in retail trade. In 1939, numerous Jewish-owned stores were located in downtown Wichita Falls. Such stores included: The Fair, a clothing store owned by Julius and Melvin Augustus, The Hub, a clothing store owned by Sol Lasky, Levine’s Department Store, opened by Morris and William Levine in 1934, which later grew into a regional chain of 150 stores, Baum’s Drug Store, owned by Marie and Chess Baum, the Popular Furniture Store, owned by Leo Schusterman, a used clothing store owned Fannie Meyer, and many others. Jews were also involved in the jewelry business in Wichita Falls. Joseph Art owned a jewelry store for many years, becoming what the local newspaper described as “one of Wichita Falls’ best-known citizens.” He was known for helping out soldiers stationed at nearby Sheppard Field, making loans to them that he never expected to be repaid. Sam Kruger opened a jewelry store in 1912, which remained in business for well over half a century; his nephew Max Kruger ran the store into the 1980s. Max became involved in local politics, serving as mayor of Wichita Falls from 1972 to 1975.

Perhaps the best known jewelry store in America got its start in Wichita Falls. Morris Zale first settled in New York after coming to the U.S. from Russia. A few years later he moved to Texas to be with his uncle, Sam Kruger, who owned a jewelry business. In 1924, with help from his uncle, Morris opened a jewelry store in Wichita Falls, offering easy credit terms and no down payment to his customers. From this modest start, the Zale Jewelry chain of stores grew, bringing jewelry to the masses and transforming an industry that had previously catered to the economic elite. At its peak, the Zale Jewelry Corporation employed 20,000 people. Although Morris moved the operation to Dallas in 1946, the foundation he created has been very philanthropic in the city where the business started. When Morris Zale died in 1995, his foundation donated $400,000 to help build a family health center in Wichita Falls.

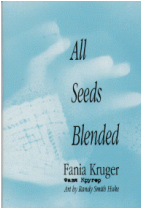

Fania Kruger

Not all Wichita Falls Jews were preoccupied with business. Fania Kruger, the wife of jewelry merchant Sam Kruger, became a celebrated poet. Kruger had left Russia as a young teenager in 1908 after her family grew concerned that her involvement with the revolutionary movement put their lives in danger. The family first settled in Fort Worth, where Fania met and married Sam. Once she moved to Wichita Falls, Fania began writing poems in English about Jewish life in Russia and America that were published in several periodicals. In 1946, she was given the highest award by the Poetry Society of America. During her career, Kruger published three collections of poetry, including The Tenth Jew, Cossack Laughter, and All Seeds Blended. Fania Kruger’s papers are held at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, one of the leading humanities archives in the country.

Not all Wichita Falls Jews were preoccupied with business. Fania Kruger, the wife of jewelry merchant Sam Kruger, became a celebrated poet. Kruger had left Russia as a young teenager in 1908 after her family grew concerned that her involvement with the revolutionary movement put their lives in danger. The family first settled in Fort Worth, where Fania met and married Sam. Once she moved to Wichita Falls, Fania began writing poems in English about Jewish life in Russia and America that were published in several periodicals. In 1946, she was given the highest award by the Poetry Society of America. During her career, Kruger published three collections of poetry, including The Tenth Jew, Cossack Laughter, and All Seeds Blended. Fania Kruger’s papers are held at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, one of the leading humanities archives in the country.

The Wichita Falls Jewish cemetery was shared by both congregations.

The Wichita Falls Jewish cemetery was shared by both congregations.

The Post-War Era

Wichita Falls entered another boom period after World War II with the construction of Sheppard Air Force Base in 1945. The city’s population doubled from 55,000 people in 1940 to 110,000 in 1955. Despite this, the Jewish community did not grow significantly. After shrinking from 385 Jews in 1937 to only 276 in 1948, they Jewish community remained at a plateau of around 260 people for the next few decades. These demographic trends affected the city’s two Jewish congregations differently.

In 1948, House of Jacob reached its peak in membership. Three years earlier, they had hired Orthodox Rabbi Morris Goodman to lead them, as Aaron Rabinowitz, who was not ordained, was given the title “Associate Rabbi.” House of Jacob had a Hebrew school, Sunday school, and held services on Friday nights and Saturday mornings. In 1957, House of Jacob moved its wood-clad building to a new location on Kemp Road. There they added new school rooms and bricked up the exterior. The mikvah was not moved to the new location; although the congregation was still nominally Orthodox, it was moving toward Conservative Judaism. At the time of the move, House of Jacob had 100 member families and about 50 students in its religious school. Rabbi Goodman remained at House of Jacob until 1968

Wichita Falls entered another boom period after World War II with the construction of Sheppard Air Force Base in 1945. The city’s population doubled from 55,000 people in 1940 to 110,000 in 1955. Despite this, the Jewish community did not grow significantly. After shrinking from 385 Jews in 1937 to only 276 in 1948, they Jewish community remained at a plateau of around 260 people for the next few decades. These demographic trends affected the city’s two Jewish congregations differently.

In 1948, House of Jacob reached its peak in membership. Three years earlier, they had hired Orthodox Rabbi Morris Goodman to lead them, as Aaron Rabinowitz, who was not ordained, was given the title “Associate Rabbi.” House of Jacob had a Hebrew school, Sunday school, and held services on Friday nights and Saturday mornings. In 1957, House of Jacob moved its wood-clad building to a new location on Kemp Road. There they added new school rooms and bricked up the exterior. The mikvah was not moved to the new location; although the congregation was still nominally Orthodox, it was moving toward Conservative Judaism. At the time of the move, House of Jacob had 100 member families and about 50 students in its religious school. Rabbi Goodman remained at House of Jacob until 1968

House of Jacob's synagogue on Kemp Road

House of Jacob's synagogue on Kemp Road

While House of Jacob grew along with the city, Temple Israel’s membership declined significantly. Between 1945 and 1965, the Reform congregation shrank from 40 contributing members to only 17. The congregation no longer had a full-time rabbi after 1945, member Paul Goldstucker usually lead services. In 1975, the remaining 15 member families of Temple Israel decided to sell their building. The congregation was too small to maintain it and its many steps made the temple inaccessible for elderly members. The city of Wichita Falls bought the building and turned it into a senior citizen center. After the sale, the congregation met for services in a rented building for a while, but soon disbanded, with the remaining members joining House of Jacob, which became the city’s sole Jewish congregation. By the time Temple Israel disbanded, House of Jacob had become a Conservative congregation. Once the remaining members of Temple Israel joined House of Jacob, the congregation adapted to accommodate both Reform and Conservative Judaism. Today, the congregation uses both Reform and Conservative prayer books, yet maintains a kosher kitchen.

Maxine Simpson

Maxine Simpson

The Community Declines

The oil industry had left Wichita Falls by the early 1960s. In response, city leaders worked successfully to attract new manufacturing to the city, but by the 1980s, many of these factories had left, as the city’s economy and population stagnated. The Jewish community began to decline as children raised in Wichita Falls moved away to larger cities. By 1975, House of Jacob had dropped to only 50 member families. Nevertheless, the congregation was able to hire full-time rabbis. In 1979, Rabbi Israel Silver came to House of Jacob, their first rabbi on staff in 11 years. He was followed a few years later by Rabbi Bremer. By the mid-1980s, the congregation no longer had a rabbi as Abraham Julius and Abe Kaufman served as lay leaders. The congregation would bring in visiting rabbis for the High Holidays. Maxine Simpson, who moved to Wichita Falls in the early 1960s, became an important leader of the congregation, using her energy and enthusiasm to help carry House of Jacob through the lean years of the 1980s and 90s.

The oil industry had left Wichita Falls by the early 1960s. In response, city leaders worked successfully to attract new manufacturing to the city, but by the 1980s, many of these factories had left, as the city’s economy and population stagnated. The Jewish community began to decline as children raised in Wichita Falls moved away to larger cities. By 1975, House of Jacob had dropped to only 50 member families. Nevertheless, the congregation was able to hire full-time rabbis. In 1979, Rabbi Israel Silver came to House of Jacob, their first rabbi on staff in 11 years. He was followed a few years later by Rabbi Bremer. By the mid-1980s, the congregation no longer had a rabbi as Abraham Julius and Abe Kaufman served as lay leaders. The congregation would bring in visiting rabbis for the High Holidays. Maxine Simpson, who moved to Wichita Falls in the early 1960s, became an important leader of the congregation, using her energy and enthusiasm to help carry House of Jacob through the lean years of the 1980s and 90s.

The Jewish Community in Wichita Falls Today

House of Jacob's sanctuary is decorated

House of Jacob's sanctuary is decorated with the old stained glass windows from Temple Israel.

In the 21st century, House of Jacob has experienced something of a resurgence. Rabbi Ira Flax was stationed at Sheppard Air Force and worked to revitalize the Wichita Falls Jewish congregation, urging them to hold weekly Shabbat services. Danny Kislin, who had spent a few years in rabbinic school, moved to Wichita Falls to manage a store. He took on the duties of lay leader, and later decided to pursue ordination. In 2011, Rabbi Danny Kislin led weekly Friday night services for the congregation. A handful of Jewish doctors have moved to town with their families while Sheppard Air Force Base continues to draw a few Jewish military families. In 2011, House of Jacob had between 30 and 40 families and an active religious school with seven students. W.B. Marks, who came back to Wichita Falls to take over the family flooring business, serves as president of the congregation.

In recent years, the M.B. and Edna Zale Foundation has helped House of Jacob, donating money to fix the roof and refurbish other features of the building. They have recently re-purposed the old stained glass windows from Temple Israel’s building which had been in storage, using portions of them to decorate both the sanctuary and the social hall. These beautiful windows are a fitting symbol of a Jewish community in touch with its historic roots that continues to keep Jewish life alive in Wichita Falls.

In recent years, the M.B. and Edna Zale Foundation has helped House of Jacob, donating money to fix the roof and refurbish other features of the building. They have recently re-purposed the old stained glass windows from Temple Israel’s building which had been in storage, using portions of them to decorate both the sanctuary and the social hall. These beautiful windows are a fitting symbol of a Jewish community in touch with its historic roots that continues to keep Jewish life alive in Wichita Falls.