Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Alexandria, Virginia

Alexandria: Historical Overview

|

Located along the western bank of the Potomac River just six miles from Washington, D.C., Alexandria, Virginia, has had many different identities since its founding in 1749. First established as a tobacco trading post, the city was later incorporated as part of the District of Columbia in 1791. By the time Virginia reclaimed the city in 1846, Alexandria had served as home to both the largest slave trading company in the nation and a large free black community. In the decades leading up to the Civil War, Alexandria became one of the busiest ports in the United States. Jews have been part of Alexandria's history since the mid-19th century.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Alexandria

Beth El Hebrew's first synagogue.

Beth El Hebrew's first synagogue. Photo courtesy of Beth El Hebrew

Early Settlers

Not coincidentally, the first Jews arrived in Alexandria during the mid-19th-century economic boom. Although there were likely a few Jewish families that settled in the city before 1850, the majority of the early Jewish community arrived in mid-1850s. Most came to the U.S. from the German states, fleeing the political revolution of 1848. They found Alexandria appealing both for its proximity to Washington and its budding commercial opportunities. By 1856, over 30 Jews had settled in the city, predominantly single men who worked as peddlers and shopkeepers selling clothing, shoes, groceries, and scrap metal. According to Rabbi Isaac Leeser, who visited Alexandria that year, these early Jewish residents “all were in good circumstances.” Though the men had not yet formed a congregation in Alexandria, many traveled to Washington Hebrew in D.C. for services. Still, Leeser enthusiastically reported in the Occident newspaper that community members recently founded the Alexandria Literary Society, led by Henry Blondheim, which Leeser hoped might foster “a successful impulse to real religious progress,” meaning the establishment of Alexandria’s own congregation. In 1857, the young Jewish community established a Hebrew Benevolent Society, which purchased a Jewish cemetery plot on Wilkes Street.

Not coincidentally, the first Jews arrived in Alexandria during the mid-19th-century economic boom. Although there were likely a few Jewish families that settled in the city before 1850, the majority of the early Jewish community arrived in mid-1850s. Most came to the U.S. from the German states, fleeing the political revolution of 1848. They found Alexandria appealing both for its proximity to Washington and its budding commercial opportunities. By 1856, over 30 Jews had settled in the city, predominantly single men who worked as peddlers and shopkeepers selling clothing, shoes, groceries, and scrap metal. According to Rabbi Isaac Leeser, who visited Alexandria that year, these early Jewish residents “all were in good circumstances.” Though the men had not yet formed a congregation in Alexandria, many traveled to Washington Hebrew in D.C. for services. Still, Leeser enthusiastically reported in the Occident newspaper that community members recently founded the Alexandria Literary Society, led by Henry Blondheim, which Leeser hoped might foster “a successful impulse to real religious progress,” meaning the establishment of Alexandria’s own congregation. In 1857, the young Jewish community established a Hebrew Benevolent Society, which purchased a Jewish cemetery plot on Wilkes Street.

Isaac Eichberg

Isaac Eichberg

Organized Jewish Life in Alexandria

By 1859, the city’s Jewish population had grown to over 50 families, and in September of that year, a group gathered to formally establish a congregation of their own, which they named Beth El. The only problem, however, was deciding how to run the upcoming High Holiday services; some favored Reform practices while others preferred Orthodox rituals. By Yom Kippur, the two factions could not settle their differences; they held two separate services, one conducted in German and the other in Hebrew. However, this factionalism did not last long. By the High Holidays in 1860, they had reunited for services led by member Henry Blondheim. For Rosh Hashanah services, the congregation rented a room in the local YMCA, and on Yom Kippur, they worshiped above Lewis Baar’s dry goods store on King Street. While the members identified as the “Reformed Israelites” of Alexandria, the congregation’s services also reflected some more traditional elements: specifically, the reader, who used the Reform prayer book Minhag America, also wore a prayer shawl and faced the Ark throughout the service, which was atypical of Reform services at the time.

By 1859, the city’s Jewish population had grown to over 50 families, and in September of that year, a group gathered to formally establish a congregation of their own, which they named Beth El. The only problem, however, was deciding how to run the upcoming High Holiday services; some favored Reform practices while others preferred Orthodox rituals. By Yom Kippur, the two factions could not settle their differences; they held two separate services, one conducted in German and the other in Hebrew. However, this factionalism did not last long. By the High Holidays in 1860, they had reunited for services led by member Henry Blondheim. For Rosh Hashanah services, the congregation rented a room in the local YMCA, and on Yom Kippur, they worshiped above Lewis Baar’s dry goods store on King Street. While the members identified as the “Reformed Israelites” of Alexandria, the congregation’s services also reflected some more traditional elements: specifically, the reader, who used the Reform prayer book Minhag America, also wore a prayer shawl and faced the Ark throughout the service, which was atypical of Reform services at the time.

Leopold Bendheim

Leopold Bendheim

The Civil War

Soon after the start of the Civil War in 1861, Union forces occupied Alexandria, where they remained throughout the war. As Virginia citizens, most Alexandrians, including the city’s Jewish residents, were sympathetic to the Southern cause. Some Beth El members—notably, Isaac Schwarz, Henry Strauss, and Samuel Lindheimer—enlisted as Confederate soldiers. Others, like shop owners Henry Schwarz, Simon Waterman, and Joseph Rosenthal, publicly supported the Confederacy by refusing to take an oath of allegiance to the Union government. Initially, the three men were indicted for their refusals, but later their cases were dropped.

Union troops used Alexandria as a major military base and medical center, and the city attracted many people seeking to capitalize on economic opportunities. Jewish merchants, in particular, flocked to Alexandria from Washington, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Norfolk, and New York, establishing numerous retail shops downtown on King Street. As one Jewish Union soldier observed, “In the principal business street, I could easily identify half the firms as belonging to the well-known Jewish nomenclature,” including two kosher boarding houses. In fact, Jewish businesses were so prominent in this district that during the High Holidays in 1862 the Alexandria Gazette reported, “the closing of so many stores on King Street gave the town quite a dull appearance.”

By 1862, the Jewish population had grown to between 300 and 400 people, many of whom joined Congregation Beth El. To accommodate its growing membership, the congregation rented rooms on the upper floors of Stewart’s Hall at the corner of King and Pitt Streets for services, with the hopes of one day purchasing its own building. In 1864, Dr. L. Schlessinger became Beth El’s first spiritual leader, and the following year Rev. H. Heilbroun succeeded him in the position. Both supplemented their income from the congregation by teaching German at area schools, setting a precedent for Beth El’s future rabbis. The congregation held a special memorial service for President Abraham Lincoln after he was assassinated on April 15, 1865.

Soon after the start of the Civil War in 1861, Union forces occupied Alexandria, where they remained throughout the war. As Virginia citizens, most Alexandrians, including the city’s Jewish residents, were sympathetic to the Southern cause. Some Beth El members—notably, Isaac Schwarz, Henry Strauss, and Samuel Lindheimer—enlisted as Confederate soldiers. Others, like shop owners Henry Schwarz, Simon Waterman, and Joseph Rosenthal, publicly supported the Confederacy by refusing to take an oath of allegiance to the Union government. Initially, the three men were indicted for their refusals, but later their cases were dropped.

Union troops used Alexandria as a major military base and medical center, and the city attracted many people seeking to capitalize on economic opportunities. Jewish merchants, in particular, flocked to Alexandria from Washington, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Norfolk, and New York, establishing numerous retail shops downtown on King Street. As one Jewish Union soldier observed, “In the principal business street, I could easily identify half the firms as belonging to the well-known Jewish nomenclature,” including two kosher boarding houses. In fact, Jewish businesses were so prominent in this district that during the High Holidays in 1862 the Alexandria Gazette reported, “the closing of so many stores on King Street gave the town quite a dull appearance.”

By 1862, the Jewish population had grown to between 300 and 400 people, many of whom joined Congregation Beth El. To accommodate its growing membership, the congregation rented rooms on the upper floors of Stewart’s Hall at the corner of King and Pitt Streets for services, with the hopes of one day purchasing its own building. In 1864, Dr. L. Schlessinger became Beth El’s first spiritual leader, and the following year Rev. H. Heilbroun succeeded him in the position. Both supplemented their income from the congregation by teaching German at area schools, setting a precedent for Beth El’s future rabbis. The congregation held a special memorial service for President Abraham Lincoln after he was assassinated on April 15, 1865.

Benedict & Julia Weil

Benedict & Julia Weil

The Late 19th Century

In the decade following the Civil War, Beth El focused its fundraising efforts toward one main goal: their own house of worship. In March 1871, for instance, the “Hebrew ladies of this city” put together a Purim ball fundraiser for both Jewish and Christian attendees; it was, according to the Alexandria Gazette, “one of the most agreeable affairs of the season,” lasting until 5 A.M. The following month, after similar community-wide efforts, along with the major financial backing from the German Cooperative Building Association (to which many Beth El members belonged), the congregation purchased a small plot of land on North Washington Street. Three months later, the new temple building was ready; on September 1, 1871, congregation leaders proudly marched through the streets of Alexandria to dedicate their new synagogue. A few months before the dedication, L. Lowensohn, Beth El’s rabbi from 1867 to 1873, began to deliver his sermons in English rather than German, ushering in a new period of Americanization for the congregation.

Indeed, by the 1870s Jews were quite assimilated and involved in Alexandria’s civic life. In 1870, clothing store owner Simon Waterman was elected to Alexandria’s Common Council, and two years later, lumber dealer and Beth El president Isaac Eichberg joined him. In 1886, Henry Strauss became Alexandria’s first Jewish mayor. Throughout his two terms in office, Strauss was known to be quite generous; according to the Alexandria Gazette, “Mr. Strauss gives…the whole of his salary to charitable and other worthy public purposes, as he is a man of large means and benevolent disposition.” Strauss, along with other members of Beth El, joined Alexandria’s men’s social clubs like the Brotherhood of the Union, the Independent Order of Red Men, and United Knights of Pythias.

Though they were assimilating to life in America, many Alexandria Jews still sought to retain aspects of their German heritage. In 1870, Lewis Stein—also a member of the city’s Common Council—founded the German Patriotic Aid Association, which sent aid to German victims of the Franco-Prussian War. In 1874, Stein, along with other Beth El members, helped to organize the German Banking Company. German Jews also established the Eintract Dramatic Association and Harmonie Association, both of which thrived as major cultural centers of singing, dancing, and theater throughout the 1870s.

Conflict returned to Beth El in 1874 when several congregants accused their new Rabbi A.A. Bonnheim of “unbecoming conduct” in executing his official duties. While most supported the rabbi, a few upset members resigned from Beth El and formed a new congregation, holding Rosh Hashanah services in Leopold Bendheim’s home. The dissenting group continued to worship as a separate congregation for two years, often bringing in readers from Washington, until Rabbi Bonnheim left Beth El in 1876 and they decided to rejoin the congregation. However, the congregation they returned to was no longer thriving as it had been; after Rabbi Bonnheim, Beth El struggled to find a replacement and activity stalled. In 1879, both Purim and Passover went by without any observance at the temple.

The congregation’s struggles continued in the next decade. Alexandria, no longer home to a bustling war economy, witnessed a mass exodus of merchants to larger cities like Baltimore, New York, and Washington. Jews were among this group. In 1882, for instance, the prominent Beth El member Lewis Stein left for Baltimore, while other active families such as the Lindheimers, Kaufmans, and Pretzfelders resettled in D.C., joining Washington Hebrew Congregation. Much of Beth El’s second generation, too, left Alexandria for larger cities. Between 1883 and 1938, Beth El’s membership fluctuated between 12 to 26 families. With such dwindling numbers, the congregation could no longer afford a full-time rabbi; instead, they hired students from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati to lead High Holiday services. In 1883, Beth El joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

The congregation still held weekly Shabbat services without a full-time rabbi, most often led by one of its three long-term presidents: Joseph Kaufmann; Isaac Eichberg; and Benedict Weil. Weil, along with Nathan Wollberg, ran the religious school until 1913, when the newly formed temple Sisterhood assumed administration of the school. The Sisterhood, led by Rosa Whitestone, soon became the heart of the small congregation; the group held lively card parties, hosted social events, and financed major building renovations. By the turn of the century, only 150 Jews remained in Alexandria, making up about one percent of the town’s 17,700 residents. By 1905, the local B’nai B’rith lodge, which had been founded around 1875, shut down due to lack of membership.

In the decade following the Civil War, Beth El focused its fundraising efforts toward one main goal: their own house of worship. In March 1871, for instance, the “Hebrew ladies of this city” put together a Purim ball fundraiser for both Jewish and Christian attendees; it was, according to the Alexandria Gazette, “one of the most agreeable affairs of the season,” lasting until 5 A.M. The following month, after similar community-wide efforts, along with the major financial backing from the German Cooperative Building Association (to which many Beth El members belonged), the congregation purchased a small plot of land on North Washington Street. Three months later, the new temple building was ready; on September 1, 1871, congregation leaders proudly marched through the streets of Alexandria to dedicate their new synagogue. A few months before the dedication, L. Lowensohn, Beth El’s rabbi from 1867 to 1873, began to deliver his sermons in English rather than German, ushering in a new period of Americanization for the congregation.

Indeed, by the 1870s Jews were quite assimilated and involved in Alexandria’s civic life. In 1870, clothing store owner Simon Waterman was elected to Alexandria’s Common Council, and two years later, lumber dealer and Beth El president Isaac Eichberg joined him. In 1886, Henry Strauss became Alexandria’s first Jewish mayor. Throughout his two terms in office, Strauss was known to be quite generous; according to the Alexandria Gazette, “Mr. Strauss gives…the whole of his salary to charitable and other worthy public purposes, as he is a man of large means and benevolent disposition.” Strauss, along with other members of Beth El, joined Alexandria’s men’s social clubs like the Brotherhood of the Union, the Independent Order of Red Men, and United Knights of Pythias.

Though they were assimilating to life in America, many Alexandria Jews still sought to retain aspects of their German heritage. In 1870, Lewis Stein—also a member of the city’s Common Council—founded the German Patriotic Aid Association, which sent aid to German victims of the Franco-Prussian War. In 1874, Stein, along with other Beth El members, helped to organize the German Banking Company. German Jews also established the Eintract Dramatic Association and Harmonie Association, both of which thrived as major cultural centers of singing, dancing, and theater throughout the 1870s.

Conflict returned to Beth El in 1874 when several congregants accused their new Rabbi A.A. Bonnheim of “unbecoming conduct” in executing his official duties. While most supported the rabbi, a few upset members resigned from Beth El and formed a new congregation, holding Rosh Hashanah services in Leopold Bendheim’s home. The dissenting group continued to worship as a separate congregation for two years, often bringing in readers from Washington, until Rabbi Bonnheim left Beth El in 1876 and they decided to rejoin the congregation. However, the congregation they returned to was no longer thriving as it had been; after Rabbi Bonnheim, Beth El struggled to find a replacement and activity stalled. In 1879, both Purim and Passover went by without any observance at the temple.

The congregation’s struggles continued in the next decade. Alexandria, no longer home to a bustling war economy, witnessed a mass exodus of merchants to larger cities like Baltimore, New York, and Washington. Jews were among this group. In 1882, for instance, the prominent Beth El member Lewis Stein left for Baltimore, while other active families such as the Lindheimers, Kaufmans, and Pretzfelders resettled in D.C., joining Washington Hebrew Congregation. Much of Beth El’s second generation, too, left Alexandria for larger cities. Between 1883 and 1938, Beth El’s membership fluctuated between 12 to 26 families. With such dwindling numbers, the congregation could no longer afford a full-time rabbi; instead, they hired students from Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati to lead High Holiday services. In 1883, Beth El joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

The congregation still held weekly Shabbat services without a full-time rabbi, most often led by one of its three long-term presidents: Joseph Kaufmann; Isaac Eichberg; and Benedict Weil. Weil, along with Nathan Wollberg, ran the religious school until 1913, when the newly formed temple Sisterhood assumed administration of the school. The Sisterhood, led by Rosa Whitestone, soon became the heart of the small congregation; the group held lively card parties, hosted social events, and financed major building renovations. By the turn of the century, only 150 Jews remained in Alexandria, making up about one percent of the town’s 17,700 residents. By 1905, the local B’nai B’rith lodge, which had been founded around 1875, shut down due to lack of membership.

The Community Grows

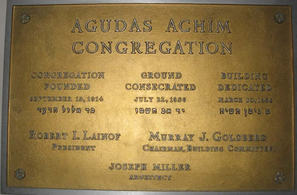

Just as the city’s Jewish population hit its lowest point, a new group of Jewish immigrants began to arrive in Alexandria. Coming from Eastern Europe, these immigrants reached Alexandria by way of Washington, Baltimore, or other East Coast port cities, so most had gained enough English and financial resources to open small clothing and dry goods stores downtown. In contrast to the German Jews, these new arrivals tended to be more Orthodox in their religious practice. Though a few of these immigrants temporarily attended Beth El Congregation, most found its Reform practices to be too foreign. By 1914, a group of 14 families organized their own Orthodox congregation, Agudas Achim, and elected clothing store owner Ben Abramson as president. Initially, the congregation held services in members’ homes, but soon rented out Sarepta Hall on King Street, which had, coincidentally, once been an occasional worship space for Beth El Congregation in its early years. Although little is known about the congregation’s early rabbis, it appears that Rev. William Finkelstein, who lived across the street from Sarepta Hall, was present at the congregation’s founding. Over the next two decades, the congregation cycled through a number of different rabbis who stayed for only a few years. When they were without a rabbi, the male members would lead weekly services.

Agudas Achim was not free of conflict. Shortly after its founding, a small faction broke away to form its own congregation, Beth Israel. Today, little is known about the short-lived congregation. In 1928, perhaps because of low membership numbers, the two competing Orthodox groups reunited, and together they purchased an old home on Wolfe Street for Agudas Achim’s first synagogue building. In 1933, the congregation acquired its own cemetery. Around the same time, the women of the congregation formed the Ladies Auxiliary of Agudas Achim, for which there was frequent praise in the synagogue minutes. The group planned Simchas Torah parties, picnics and installation dinners, and fundraisers for renovation projects. In 1937, formally recognizing the women’s contributions, the previously all-male synagogue board appointed two women to join them.

Just as the city’s Jewish population hit its lowest point, a new group of Jewish immigrants began to arrive in Alexandria. Coming from Eastern Europe, these immigrants reached Alexandria by way of Washington, Baltimore, or other East Coast port cities, so most had gained enough English and financial resources to open small clothing and dry goods stores downtown. In contrast to the German Jews, these new arrivals tended to be more Orthodox in their religious practice. Though a few of these immigrants temporarily attended Beth El Congregation, most found its Reform practices to be too foreign. By 1914, a group of 14 families organized their own Orthodox congregation, Agudas Achim, and elected clothing store owner Ben Abramson as president. Initially, the congregation held services in members’ homes, but soon rented out Sarepta Hall on King Street, which had, coincidentally, once been an occasional worship space for Beth El Congregation in its early years. Although little is known about the congregation’s early rabbis, it appears that Rev. William Finkelstein, who lived across the street from Sarepta Hall, was present at the congregation’s founding. Over the next two decades, the congregation cycled through a number of different rabbis who stayed for only a few years. When they were without a rabbi, the male members would lead weekly services.

Agudas Achim was not free of conflict. Shortly after its founding, a small faction broke away to form its own congregation, Beth Israel. Today, little is known about the short-lived congregation. In 1928, perhaps because of low membership numbers, the two competing Orthodox groups reunited, and together they purchased an old home on Wolfe Street for Agudas Achim’s first synagogue building. In 1933, the congregation acquired its own cemetery. Around the same time, the women of the congregation formed the Ladies Auxiliary of Agudas Achim, for which there was frequent praise in the synagogue minutes. The group planned Simchas Torah parties, picnics and installation dinners, and fundraisers for renovation projects. In 1937, formally recognizing the women’s contributions, the previously all-male synagogue board appointed two women to join them.

Rabbi Hugo Schiff

Rabbi Hugo Schiff

Despite this new wave of immigration, the Jewish population of Alexandria remained low, with only 140 people in 1927. Beth El remained quite small. Nevertheless, in November, 1938, Beth El President Benedict Weil called a special meeting of the congregation’s 23 members to discuss the hiring of their first rabbi in over 50 years. Specifically, Weil sought to hire Rabbi Hugh Schiff of Karlsruhe, Germany, to help him escape from Nazi rule. The congregation reacted overwhelmingly in favor of Weil’s proposal, and in April 1939—largely under the sponsorship of Beth El member Sylvan Laupheimer—Rabbi Schiff arrived in Alexandria, bringing with him a Torah from his former congregation in Karlsruhe. During his ten-year tenure at Beth El, Rabbi Schiff reinvigorated all areas of the congregation’s life, from Adult Education to the Temple Brotherhood. During World War II, Rabbi Schiff served as the Jewish chaplain at Fort Belvoir, a nearby military base, as well as vice president of the Alexandria Ministerial Association. By the time Rabbi Schiff left in 1949, Beth El’s membership had increased to over 100 families.

Agudas Achim also mobilized its membership in the wake of World War II. Most significantly, the congregation lent one of their Torahs to the Quantico Marine Corps, and often welcomed soldiers from the nearby Fort Humphreys for Friday night services.

Agudas Achim also mobilized its membership in the wake of World War II. Most significantly, the congregation lent one of their Torahs to the Quantico Marine Corps, and often welcomed soldiers from the nearby Fort Humphreys for Friday night services.

Beth El Hebrew's 1957 temple

Beth El Hebrew's 1957 temple

The Mid-20th Century

After the war, both congregations experienced enormous growth, primarily due to three broader trends effecting Alexandria’s population. First, many of the federal government employees and military personnel who had arrived in Washington at the beginning of World War II remained in the region as the federal government continued to expand. Second, the newly built Capital Beltway granted much easier access between D.C. and Alexandria. Third, as suburbanization occurred across the country, many Washington professionals moved out to Northern Virginia. Alexandria—just six miles from D.C.—was an ideal location. By the late 1950s, Alexandria’s formerly Southern character had quickly faded, instead transforming into a D.C. suburb home to thousands of federal employees.

Consequently, membership at both congregations skyrocketed. Beth El, under the four-year tenure Rabbi Melvin Helfgott, reached 180 families by 1953. Early in his tenure, Rabbi Helfgott attracted new members by transitioning from sermons to Friday evening adult discussions. He also created a “young married” group in January 1952, bringing new families to the congregation. As a result, the Sunday school and Temple Sisterhood both doubled within three years.

After the war, both congregations experienced enormous growth, primarily due to three broader trends effecting Alexandria’s population. First, many of the federal government employees and military personnel who had arrived in Washington at the beginning of World War II remained in the region as the federal government continued to expand. Second, the newly built Capital Beltway granted much easier access between D.C. and Alexandria. Third, as suburbanization occurred across the country, many Washington professionals moved out to Northern Virginia. Alexandria—just six miles from D.C.—was an ideal location. By the late 1950s, Alexandria’s formerly Southern character had quickly faded, instead transforming into a D.C. suburb home to thousands of federal employees.

Consequently, membership at both congregations skyrocketed. Beth El, under the four-year tenure Rabbi Melvin Helfgott, reached 180 families by 1953. Early in his tenure, Rabbi Helfgott attracted new members by transitioning from sermons to Friday evening adult discussions. He also created a “young married” group in January 1952, bringing new families to the congregation. As a result, the Sunday school and Temple Sisterhood both doubled within three years.

Sanctuary at Agudas Achim

Sanctuary at Agudas Achim

With increasing membership, congregation leaders began to discuss building a new synagogue. In 1952, under the lay leadership of Leroy Blondheim, the congregation purchased a lot on King Street; however, within just a few years—as Beth El’s membership continued to expand to over 400 families by 1960—even this new lot was no longer suitable. The need for a new building was especially pressing by 1955, when the 84-year-old Washington Street temple could no longer accommodate its members for Friday night services. As Rabbi Emmet Frank put it, the sanctuary “fit like Junior’s last year’s clothes.” For two years, while searching for a new home, the congregation held Friday night services at Fairlington United Methodist Church. Finally, on February 10, 1957, Congregation Beth El began to build a new temple on Seminary Road, complete with a 400-person sanctuary and 18 classrooms. The congregation continues to use the building today. To show their appreciation, congregants of Beth El presented a gift to Fairlington United Methodist Church in 1957. In February 1958, the two congregations began and continue to celebrate an annual dinner renewing their friendship.

Agudas Achim witnessed similar growth during the post-war period. In 1945, as its demographics continued to shift toward more American-born congregants, the congregation voted to affiliate with the Conservative movement. In 1947, Rabbi Saul Lehman, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary, arrived as the congregation’s first Conservative rabbi. That same year, congregation leaders sold the Wolfe Street synagogue and began the hunt for a new, larger space. The search continued for 11 years—during which the congregation worshiped in a remodeled home on Russell Road—until Agudas Achim finally found a suitable location on Valley Drive. On March 30, 1958, the new building was finally ready for use, which the congregation celebrated with a motorcade processional from Russell Road to Valley Drive. At the time, Agudas Achim’s membership had reached about 175 families. By 1960, Alexandria’s Jewish community had grown to 6,400 people, with a large portion working in government-related fields.

Agudas Achim witnessed similar growth during the post-war period. In 1945, as its demographics continued to shift toward more American-born congregants, the congregation voted to affiliate with the Conservative movement. In 1947, Rabbi Saul Lehman, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary, arrived as the congregation’s first Conservative rabbi. That same year, congregation leaders sold the Wolfe Street synagogue and began the hunt for a new, larger space. The search continued for 11 years—during which the congregation worshiped in a remodeled home on Russell Road—until Agudas Achim finally found a suitable location on Valley Drive. On March 30, 1958, the new building was finally ready for use, which the congregation celebrated with a motorcade processional from Russell Road to Valley Drive. At the time, Agudas Achim’s membership had reached about 175 families. By 1960, Alexandria’s Jewish community had grown to 6,400 people, with a large portion working in government-related fields.

The Civil Rights Era

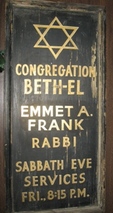

While Alexandria had become a suburb of D.C., it still had to face the difficult issue of civil rights. Beth El’s Rabbi Emmet Frank, in particular, directly confronted the civil rights issue during his tenure from 1954 to 1969. In his Yom Kippur sermon in 1955, Rabbi Frank spoke out against Virginia’s segregationist policies, reminding his congregation that “the Jew cannot remain silent to injustice against anyone.” While some members criticized Rabbi Frank for his political address and feared an anti-Semitic backlash, most ultimately supported his call to social justice. Eleven Christian ministers in the community commended Rabbi Frank’s efforts, as did temple president Leroy Bendheim, who was also serving as mayor of Alexandria at the time. Still, others felt threatened by Rabbi Frank’s words. On October 19, 1958, just before he was scheduled to speak at Arlington’s Unitarian Church, the church received an anonymous bomb threat, so the evening was canceled. The threat received national attention, and was even covered by the Jerusalem Post. By 1966, Rabbi Frank had reached national prominence, and he even offered the opening prayer in the U.S. Senate.

While Alexandria had become a suburb of D.C., it still had to face the difficult issue of civil rights. Beth El’s Rabbi Emmet Frank, in particular, directly confronted the civil rights issue during his tenure from 1954 to 1969. In his Yom Kippur sermon in 1955, Rabbi Frank spoke out against Virginia’s segregationist policies, reminding his congregation that “the Jew cannot remain silent to injustice against anyone.” While some members criticized Rabbi Frank for his political address and feared an anti-Semitic backlash, most ultimately supported his call to social justice. Eleven Christian ministers in the community commended Rabbi Frank’s efforts, as did temple president Leroy Bendheim, who was also serving as mayor of Alexandria at the time. Still, others felt threatened by Rabbi Frank’s words. On October 19, 1958, just before he was scheduled to speak at Arlington’s Unitarian Church, the church received an anonymous bomb threat, so the evening was canceled. The threat received national attention, and was even covered by the Jerusalem Post. By 1966, Rabbi Frank had reached national prominence, and he even offered the opening prayer in the U.S. Senate.

Rabbi Emmet Frank

Rabbi Emmet Frank

Still, not everyone at Beth El supported Rabbi Frank and his outspoken ways. In 1962, when he wrote a letter published in the Washington Post declaring that he saw nothing wrong with Christmas and Chanukah observances in public schools, many congregants were greatly upset. This faction began to campaign against his total rabbinic freedom in favor of “lay guidance, counsel and assistance,” and when board elections took place in May that year, this dissenting group—led by Emanuel Kintisch and Harold Silverstein— decided to run its own set of candidates for the board. While the election garnered a record turnout, the opposition members ultimately lost, and Rabbi Frank remained as spiritual leader. As a result, 43 families left Beth El to establish a new congregation, Temple Rodef Shalom in Falls Church, Virginia. At the time, the split appeared to be quite damaging to Beth El, but over time, as the Jewish population of Northern Virginia continued to swell, the need for a second Reform temple seemed inevitable. Today, Rodef Shalom,which now has over 1500 households, is quite friendly with Beth El, and the two often host joint activities.

Rabbi Sheldon Elster

Rabbi Sheldon Elster

The Late 20th Century

After Rabbi Frank left Alexandria in 1969, his successor, Rabbi Arnold Fink, who served Beth El from 1969 to 2002, continued his legacy of Jewish-inspired activism, which occasionally landed him in difficult situations. In 1988, for instance, while traveling to the Soviet Union, Fink and an Episcopal priest were detained in jail for a few hours after authorities found menorot, mezuzot, and other Judaica that they had smuggled into the country. Thankfully, the KGB could not crack the code names and addresses of Jewish families that Fink had written in a crossword puzzle, so they were released. One of the families that Fink met on that trip, the Turkeltaub-Rabins, immigrated to America a year and a half later and became active members of Beth El Congregation.

At Agudas Achim, Rabbi Sheldon Elster also emphasized interfaith work and community justice upon his arrival in 1968. That year, the congregation transitioned to egalitarian worship, celebrating the b’nei mitzvah of girls as well as boys. Ellen Naomi Cohen—perhaps better known as Cass Elliot, the legendary singer in The Mamas and the Papas—became the first bat mitzvah at Agudas Achim. Rabbi Elster often engaged the larger community, giving provocative talks such as “Civil Disobedience,” “Poverty and Protest,” and “Who is a Jew?” His wife Dr. Shulamith Elster participated in a local women’s interfaith group and worked to help recently arrived Soviet Jews resettle in the D.C. area. In 1982, Rabbi Elster partnered with Rabbi Fink of Beth El and local parents to establish the Gesher Day School, Northern Virginia’s first Jewish preschool. Today, the day school has grown to accommodate Jewish students from kindergarten to eighth grade.

After Rabbi Frank left Alexandria in 1969, his successor, Rabbi Arnold Fink, who served Beth El from 1969 to 2002, continued his legacy of Jewish-inspired activism, which occasionally landed him in difficult situations. In 1988, for instance, while traveling to the Soviet Union, Fink and an Episcopal priest were detained in jail for a few hours after authorities found menorot, mezuzot, and other Judaica that they had smuggled into the country. Thankfully, the KGB could not crack the code names and addresses of Jewish families that Fink had written in a crossword puzzle, so they were released. One of the families that Fink met on that trip, the Turkeltaub-Rabins, immigrated to America a year and a half later and became active members of Beth El Congregation.

At Agudas Achim, Rabbi Sheldon Elster also emphasized interfaith work and community justice upon his arrival in 1968. That year, the congregation transitioned to egalitarian worship, celebrating the b’nei mitzvah of girls as well as boys. Ellen Naomi Cohen—perhaps better known as Cass Elliot, the legendary singer in The Mamas and the Papas—became the first bat mitzvah at Agudas Achim. Rabbi Elster often engaged the larger community, giving provocative talks such as “Civil Disobedience,” “Poverty and Protest,” and “Who is a Jew?” His wife Dr. Shulamith Elster participated in a local women’s interfaith group and worked to help recently arrived Soviet Jews resettle in the D.C. area. In 1982, Rabbi Elster partnered with Rabbi Fink of Beth El and local parents to establish the Gesher Day School, Northern Virginia’s first Jewish preschool. Today, the day school has grown to accommodate Jewish students from kindergarten to eighth grade.

The Jewish Community in Alexandria Today

In 1987, Rabbi Jack Moline succeeded Rabbi Elster as Agudas Achim’s spiritual leader. Since then, the congregation has grown to about 550 families, most of whom work in government-related fields. Several prominent government officials have been active members of Agudas Achim. When Rahm Emanuel worked in the White House and served in congress, he and his family attended the congregation. Today, Agudas Achim maintains an active Sisterhood, men’s club, and a religious school with about 125 students.

Beth El, too, continues to thrive with about 600 families. In 1986, given the huge influx of Jews settling across Northern Virginia, Beth El’s assistant rabbi Amy Perlin left to start a new congregation in Fairfax Station, which allowed many former Beth El congregants to worship closer to their homes. The new congregation, Temple B’nai Shalom, has quickly grown from 125 to 450 families since its establishment. Meanwhile, Beth El has flourished under the leadership of Rabbi Brett Isserow since 2002. The congregation continues its long history of social engagement and service through numerous projects such as the Beth El House, a program that helps formerly homeless families gain economic and child-rearing skills. Beth El’s Women of Reform Judaism chapter, brotherhood, and religious school, which has about 200 students, remain active as well.

In 2013, about 5,000 Jews lived in Alexandria, with thousands more in the surrounding northern Virginia region.While Beth El and Agudas Achim have expanded well beyond the small congregations they once were, both continue to preserve the warmth and family spirit of their early days worshiping above King Street stores.

Beth El, too, continues to thrive with about 600 families. In 1986, given the huge influx of Jews settling across Northern Virginia, Beth El’s assistant rabbi Amy Perlin left to start a new congregation in Fairfax Station, which allowed many former Beth El congregants to worship closer to their homes. The new congregation, Temple B’nai Shalom, has quickly grown from 125 to 450 families since its establishment. Meanwhile, Beth El has flourished under the leadership of Rabbi Brett Isserow since 2002. The congregation continues its long history of social engagement and service through numerous projects such as the Beth El House, a program that helps formerly homeless families gain economic and child-rearing skills. Beth El’s Women of Reform Judaism chapter, brotherhood, and religious school, which has about 200 students, remain active as well.

In 2013, about 5,000 Jews lived in Alexandria, with thousands more in the surrounding northern Virginia region.While Beth El and Agudas Achim have expanded well beyond the small congregations they once were, both continue to preserve the warmth and family spirit of their early days worshiping above King Street stores.