Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Charlottesville, Virginia

Charlottesville: Historical Overview

|

Situated in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, Charlottesville is a regional hub of commerce, health care, and higher education. Named for Queen Charlotte of England, Charlottesville has been a fixture in American history since the Revolutionary War when the town housed barracks for German and British prisoners. The construction of a rail line in 1850 established Charlottesville as a major shipping hub and spurred tremendous growth. After World War II, the G.I. Bill helped turn the University of Virginia into the city’s biggest employer. Anchored today by the University of Virginia and nearby apple orchards, vineyards, and small scale farms, Charlottesville has a reputation as one of the country’s best places to live. Jews have lived in Charlotte since the 18th century

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Charlottesville

Early Settlers

The first Jewish residents arrived in Charlottesville well before the town’s two most iconic institutions, Monticello and the University of Virginia, were established. In 1757 Michael and Sarah Israel acquired 80 acres of land just south of town between North Garden and Batesville, an area now known as Israel’s Gap. Nearby Israel’s Mountain is also named for the family. Solomon Israel, a relative of Michael and Sarah, purchased land near Mechums River in 1764.

The first Jewish residents arrived in Charlottesville well before the town’s two most iconic institutions, Monticello and the University of Virginia, were established. In 1757 Michael and Sarah Israel acquired 80 acres of land just south of town between North Garden and Batesville, an area now known as Israel’s Gap. Nearby Israel’s Mountain is also named for the family. Solomon Israel, a relative of Michael and Sarah, purchased land near Mechums River in 1764.

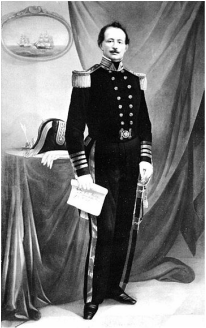

Uriah P. Levy

Uriah P. Levy

Jews and Jefferson's Institutions

Charlottesville’s long tradition of Jewish-owned businesses dates back to the early 19th century when several Jewish merchants lived in town. Thomas Jefferson wrote in an 1825 letter that Isaac Raphael, a Jewish dry good store owner, “holds my little bank here.” David Isaacs, another Jewish dry good store owner during the 1820s and 1830s, was well known for his friendship with Jefferson and his common law marriage with Nancy West, a black woman with whom he had seven children. He sold Jefferson everything from cheese to a horse and regularly sent him books, sermons, and pamphlets about Judaism.

Isaacs’ relationship with West, who owned real estate and a bakery, was groundbreaking for the time period. The two never officially married because interracial marriage was illegal in Virginia and West was not Jewish. Legal authorities attempted to prosecute the couple for fornication in 1826. The charges were dropped after the court determined that since Isaacs and West acted as husband and wife their actions could not be characterized as promiscuous. They lived together until Isaacs’ death in 1837. Isaacs was affiliated with Richmond’s Beth Shalome synagogue throughout his life and is buried in their cemetery.

After Thomas Jefferson’s death in 1826, a local pharmacist bought his Monticello home in an ill-fated attempt to turn it into a silk worm plantation. By the time Commodore Uriah P. Levy, a Jewish naval captain of Sephardic heritage, purchased Monticello in 1836 for $2,700, the once stately home was run down from mismanagement and neglect. Levy’s desire to purchase the home stemmed from his adoration of Jefferson. He had several brushes with anti-Semitism throughout his life and naval career and admired Jefferson’s belief in religious liberty. Levy initiated a series of major restorations. He quickly hired Joel Wheeler as a full time caretaker and purchased slaves who refurbished the home’s interior and exterior and revived the estate’s once blooming gardens. A few years after purchasing Monticello, Levy opened the property to tourists and was known for guiding visitors through the grounds.

Charlottesville’s long tradition of Jewish-owned businesses dates back to the early 19th century when several Jewish merchants lived in town. Thomas Jefferson wrote in an 1825 letter that Isaac Raphael, a Jewish dry good store owner, “holds my little bank here.” David Isaacs, another Jewish dry good store owner during the 1820s and 1830s, was well known for his friendship with Jefferson and his common law marriage with Nancy West, a black woman with whom he had seven children. He sold Jefferson everything from cheese to a horse and regularly sent him books, sermons, and pamphlets about Judaism.

Isaacs’ relationship with West, who owned real estate and a bakery, was groundbreaking for the time period. The two never officially married because interracial marriage was illegal in Virginia and West was not Jewish. Legal authorities attempted to prosecute the couple for fornication in 1826. The charges were dropped after the court determined that since Isaacs and West acted as husband and wife their actions could not be characterized as promiscuous. They lived together until Isaacs’ death in 1837. Isaacs was affiliated with Richmond’s Beth Shalome synagogue throughout his life and is buried in their cemetery.

After Thomas Jefferson’s death in 1826, a local pharmacist bought his Monticello home in an ill-fated attempt to turn it into a silk worm plantation. By the time Commodore Uriah P. Levy, a Jewish naval captain of Sephardic heritage, purchased Monticello in 1836 for $2,700, the once stately home was run down from mismanagement and neglect. Levy’s desire to purchase the home stemmed from his adoration of Jefferson. He had several brushes with anti-Semitism throughout his life and naval career and admired Jefferson’s belief in religious liberty. Levy initiated a series of major restorations. He quickly hired Joel Wheeler as a full time caretaker and purchased slaves who refurbished the home’s interior and exterior and revived the estate’s once blooming gardens. A few years after purchasing Monticello, Levy opened the property to tourists and was known for guiding visitors through the grounds.

Monticello

Monticello

Following his death in 1862, Levy left Monticello to the United States government, but the property remained in legal limbo because of the Civil War. In 1879, Levy’s nephew Jefferson Monroe Levy purchased the property at an auction for $10,500. Like his uncle, the younger Levy invested in major renovations of the property. Though Jefferson Levy only lived at Monticello during the summer, spending much of his time in New York where he owned real estate and later served in congress, he was active in Charlottesville’s affairs. He hosted a community-wide open house and fireworks show every July 4th at Monticello. In 1880 he financed the restoration of the Town Hall into an opera house and in 1887 formally bought the building which was subsequently renamed the Levy Opera House. Levy hired Jacob Leterman and Ernest Oberdorfer, members of two prominent Charlottesville Jewish families, to manage the daily operations of the theatre. Leterman left in 1896 to open the Jefferson Auditorium, which was more successful than the Levy Opera House until the auditorium was destroyed in a 1907 fire. The Levy Opera House hosted many traveling productions until it closed in 1912.

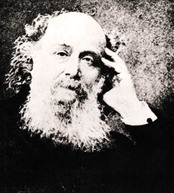

James Joseph Sylvester

James Joseph Sylvester

Monticello remained in the Levy family until 1923 when the Thomas Jefferson Foundation purchased the home for $500,000. The sale came on the heels of nearly two decades of public pressure from government officials and newspaper editors encouraging Levy to give Monticello to the government. After the sale of Monticello, memory of the Levy family’s contributions to the estate nearly disappeared for 60 years. There was scant mention of the family’s role in the rehabilitation of the property in guidebooks and tour guides did not discuss the Levy’s contributions. In 1985, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation unveiled a restored plaque at Rachel Levy’s grave site and began to include the Levy family in Monticello’s historical narrative. Despite having a presence in Charlottesville for nearly 80 years, the Levy family never took a role in the local Jewish community. Even after Congregation Beth Israel opened its doors in 1882, Uriah P. Levy and Jefferson Levy both remained members of New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel, and are both buried in Brooklyn.

James Joseph Sylvester arrived from England in the fall of 1841 to work at Jefferson’s other cherished legacy, the University of Virginia. With his appointment as a professor of mathematics, Sylvester became the first observant Jew in the United States to teach a secular subject at an American university. Sylvester’s tenure at U.Va was short lived. He never felt truly comfortable with his students and local Protestant groups were unhappy that the university had hired a Jew. The Richmond based newspaper the Watchman of the South, sponsored by the state’s powerful Presbyterian Church, lambasted his hiring. Students did not appreciate Sylvester’s abolitionist views and frequently challenged his authority in class. After using his cane sword during an altercation with a student, Sylvester submitted his resignation on March 22, 1842. After leaving U.Va, Sylvester later taught at Johns Hopkins and Oxford Universities, becoming the first Jewish professor in Oxford’s history.

James Joseph Sylvester arrived from England in the fall of 1841 to work at Jefferson’s other cherished legacy, the University of Virginia. With his appointment as a professor of mathematics, Sylvester became the first observant Jew in the United States to teach a secular subject at an American university. Sylvester’s tenure at U.Va was short lived. He never felt truly comfortable with his students and local Protestant groups were unhappy that the university had hired a Jew. The Richmond based newspaper the Watchman of the South, sponsored by the state’s powerful Presbyterian Church, lambasted his hiring. Students did not appreciate Sylvester’s abolitionist views and frequently challenged his authority in class. After using his cane sword during an altercation with a student, Sylvester submitted his resignation on March 22, 1842. After leaving U.Va, Sylvester later taught at Johns Hopkins and Oxford Universities, becoming the first Jewish professor in Oxford’s history.

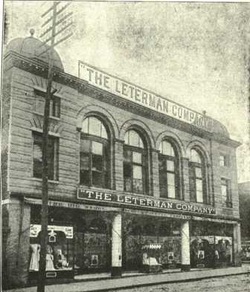

Leterman Company Department Store

Leterman Company Department Store

The Community Grows

The wave of German Jewish immigration to the United States in mid-19th century fueled the growth of Charlottesville’s Jewish community. The families that would arrive during this era would become major figures in the town’s commercial, civic, and religious life for decades to come. Bernard Oberdorfer, a Wurttemberg native, arrived in Charlottesville as a peddler after a stint at a cigar factory in New York. A veteran of the Confederate Army, he opened a downtown store that his eldest son Philip would eventually run.

The Leterman brothers, Simon and Isaac, were born in Wurttemberg and established their Main Street shop in Charlottesville about 1852. During the Civil War, the brothers fought on opposite sides. Simon joined the Confederate Army and his wife Hannah volunteered as a nurse for Confederate forces, while Isaac enlisted with the Union army. Simon, Hannah and their ten children would leave an indelible mark in Charlottesville. Hannah, nicknamed “Mother Leterman” for her efforts in combating poverty, was a founder of the town’s White Ribbon Temperance Society chapter and the Ladies Aid Society of Charlottesville. Simon became a director of the Peoples National Bank when it was formed in 1875 and was one of the original trustees of Congregation Beth Israel. Five of their sons established the Leterman Company Department Store, which quickly became Charlottesville’s largest department stores when it opened its doors in 1899, though it closed in 1908 because of financial problems.

The civic spirit of Simon and Hannah was passed down to their children who were heavily involved in Charlottesville’s civic life. Moses Leterman was a city councilman, vice president of the Peoples National Bank, and held officer positions with several local companies. His brothers J.J., Ben, and Phil were involved in the school board, Elks Lodge and bringing opera to the town. This tradition of civic involvement continued until the 1950s, when the last descendants left Charlottesville.

Isaac and Simon Leterman’s nephew, Moses Kaufman, became the patriarch of Charlottesville’s third founding Jewish family. Kaufman arrived in the United States with the help of his uncles and opened a clothing store on Main Street, across the street from the Oberdorfer’s store in 1861. A serial entrepreneur, Kaufman also manufactured cigars and slate pencils while also owning a whiskey warehouse. Kaufman’s store was located on the same site as David Isaacs’ store. Kaufman’s sons Sol and Mortimer took over the clothing store following Moses’ death in 1898. Like his uncles, Moses Kaufman was deeply involved in Charlottesville’s civic affairs, a tradition he would pass onto his sons. He was a member of the city’s inaugural school board, president of the Town Council, active in the local Democratic Party, a founder of the local Chamber of Commerce, and a member of various other local organizations. He was so beloved in the community that schools were closed the day of his funeral in 1898 allowing students and teachers to attend. Mortimer would follow his father onto the school board while Sol was a founding member and crucial financial supporter of the city’s municipal band, which would go on to play for the Queen of England and four presidents.

The wave of German Jewish immigration to the United States in mid-19th century fueled the growth of Charlottesville’s Jewish community. The families that would arrive during this era would become major figures in the town’s commercial, civic, and religious life for decades to come. Bernard Oberdorfer, a Wurttemberg native, arrived in Charlottesville as a peddler after a stint at a cigar factory in New York. A veteran of the Confederate Army, he opened a downtown store that his eldest son Philip would eventually run.

The Leterman brothers, Simon and Isaac, were born in Wurttemberg and established their Main Street shop in Charlottesville about 1852. During the Civil War, the brothers fought on opposite sides. Simon joined the Confederate Army and his wife Hannah volunteered as a nurse for Confederate forces, while Isaac enlisted with the Union army. Simon, Hannah and their ten children would leave an indelible mark in Charlottesville. Hannah, nicknamed “Mother Leterman” for her efforts in combating poverty, was a founder of the town’s White Ribbon Temperance Society chapter and the Ladies Aid Society of Charlottesville. Simon became a director of the Peoples National Bank when it was formed in 1875 and was one of the original trustees of Congregation Beth Israel. Five of their sons established the Leterman Company Department Store, which quickly became Charlottesville’s largest department stores when it opened its doors in 1899, though it closed in 1908 because of financial problems.

The civic spirit of Simon and Hannah was passed down to their children who were heavily involved in Charlottesville’s civic life. Moses Leterman was a city councilman, vice president of the Peoples National Bank, and held officer positions with several local companies. His brothers J.J., Ben, and Phil were involved in the school board, Elks Lodge and bringing opera to the town. This tradition of civic involvement continued until the 1950s, when the last descendants left Charlottesville.

Isaac and Simon Leterman’s nephew, Moses Kaufman, became the patriarch of Charlottesville’s third founding Jewish family. Kaufman arrived in the United States with the help of his uncles and opened a clothing store on Main Street, across the street from the Oberdorfer’s store in 1861. A serial entrepreneur, Kaufman also manufactured cigars and slate pencils while also owning a whiskey warehouse. Kaufman’s store was located on the same site as David Isaacs’ store. Kaufman’s sons Sol and Mortimer took over the clothing store following Moses’ death in 1898. Like his uncles, Moses Kaufman was deeply involved in Charlottesville’s civic affairs, a tradition he would pass onto his sons. He was a member of the city’s inaugural school board, president of the Town Council, active in the local Democratic Party, a founder of the local Chamber of Commerce, and a member of various other local organizations. He was so beloved in the community that schools were closed the day of his funeral in 1898 allowing students and teachers to attend. Mortimer would follow his father onto the school board while Sol was a founding member and crucial financial supporter of the city’s municipal band, which would go on to play for the Queen of England and four presidents.

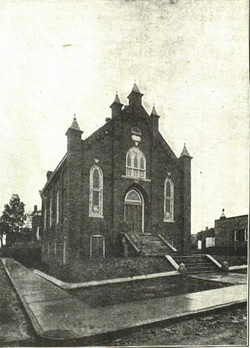

Beth Israel in its original location

Beth Israel in its original location

Organized Jewish Life in Charlottesville

In addition to being involved in civic and commercial life, the Letermans, Kaufmans and Oberdorfers were instrumental in establishing Jewish religious life in Charlottesville. Isaac Leterman and Bernard Oberdorfer purchased property for a Jewish cemetery in 1870, deeding it to the Charlottesville Hebrew Benevolent Society. Eight years after the purchase of the cemetery, about 100 Jewish people were living in the town. In 1882, the Hebrew Benevolent Society became Congregation Beth Israel and opened a synagogue at Market and Second Street. Aaron Brunn became the congregation’s first president. Beth Israel moved to a new location on Jefferson and Third Streets in 1904 when the government purchased their old property to build a post office. According to legend, the synagogue was disassembled and rebuilt brick by brick on the new site.

Beth Israel hired Rabbi William Weinstein in 1883, though he would leave after a few years most likely because the congregation could no longer afford a rabbi. After the departure of Rabbi Weinstein, services were led primarily by Moses Kaufman and later his son Mortimer. Lay leaders like the Kaufmans would continue to lead services at Beth Israel until the congregation was able to hire a full-time rabbi in the late 1970s.

The large-scale immigration of Eastern European Jews to the United States brought a wave of new Jewish families to Charlottesville in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Families from Eastern European backgrounds like the Shaperos, Rubins and Walters would open department stores and become active in Beth Israel. By the 1920s and early 1930s the Walters and O’Mansky families emerged as leaders of the Jewish community as the three founding Jewish families gradually moved away, died, or no longer took active leadership roles in Jewish life. Isaac Walters, who ran the Shapero and Walters department store, was Beth Israel’s president from 1919 to 1944 in addition to running the Sunday school. His wife Florence Shapero Walters established the synagogue’s Sisterhood in 1927. Harry and June O’Mansky arrived in Charlottesville in 1930 from Emporia, Virginia, and purchased the Young Men’s Clothing Store. The O’Manskys became deeply involved in Jewish life. June was elected the first president of the local Hadassah chapter in 1938 and Harry served as synagogue president from 1955 to 1964.

In addition to being involved in civic and commercial life, the Letermans, Kaufmans and Oberdorfers were instrumental in establishing Jewish religious life in Charlottesville. Isaac Leterman and Bernard Oberdorfer purchased property for a Jewish cemetery in 1870, deeding it to the Charlottesville Hebrew Benevolent Society. Eight years after the purchase of the cemetery, about 100 Jewish people were living in the town. In 1882, the Hebrew Benevolent Society became Congregation Beth Israel and opened a synagogue at Market and Second Street. Aaron Brunn became the congregation’s first president. Beth Israel moved to a new location on Jefferson and Third Streets in 1904 when the government purchased their old property to build a post office. According to legend, the synagogue was disassembled and rebuilt brick by brick on the new site.

Beth Israel hired Rabbi William Weinstein in 1883, though he would leave after a few years most likely because the congregation could no longer afford a rabbi. After the departure of Rabbi Weinstein, services were led primarily by Moses Kaufman and later his son Mortimer. Lay leaders like the Kaufmans would continue to lead services at Beth Israel until the congregation was able to hire a full-time rabbi in the late 1970s.

The large-scale immigration of Eastern European Jews to the United States brought a wave of new Jewish families to Charlottesville in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Families from Eastern European backgrounds like the Shaperos, Rubins and Walters would open department stores and become active in Beth Israel. By the 1920s and early 1930s the Walters and O’Mansky families emerged as leaders of the Jewish community as the three founding Jewish families gradually moved away, died, or no longer took active leadership roles in Jewish life. Isaac Walters, who ran the Shapero and Walters department store, was Beth Israel’s president from 1919 to 1944 in addition to running the Sunday school. His wife Florence Shapero Walters established the synagogue’s Sisterhood in 1927. Harry and June O’Mansky arrived in Charlottesville in 1930 from Emporia, Virginia, and purchased the Young Men’s Clothing Store. The O’Manskys became deeply involved in Jewish life. June was elected the first president of the local Hadassah chapter in 1938 and Harry served as synagogue president from 1955 to 1964.

The O'Mansky's store in downtown

The O'Mansky's store in downtown

The First Half of the 20th Century

Despite the influx of Eastern European Jews, Beth Israel remained a Reform congregation, having joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations by 1900. The congregation used an organ, had a choir with Christian members, conducted services in English, and did not require men to wear head coverings, all hallmarks of classical Reform practices. Numbering only 12 contributing members in 1910, Beth Israel soon dropped its UAHC membership, though it rejoined in 1927. By 1930, the congregation had 24 contributing members.

These Reform practices made Charlottesville’s more traditional Eastern European Jewish community uncomfortable, although the community was too small to support a second Jewish congregation. For years, more traditional Jews held separate High Holiday services in the synagogue basement or above the O’Manskys store. In 1931, Morris Massing organized a regular Orthodox service that also met above the O’Manskys store. The group was comprised of U.Va students who Massing would pick up from campus on Friday nights, as well as members of Beth Israel. This informal group lasted until the 1940s and hosted the only bar mitzvah ceremonies in Charlottesville during a 50-year period.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Jewish-owned stores dominated Charlottesville’s downtown. Businesses owned by Levy, Cohen, Eitelman, Zimmerman, and Rosenblock families dotted Charlottesville’s Main Street. During the High Holidays, much of the business district was closed.

The late 1920s had marked the beginning of a period of stagnation and decline in the Jewish community. In 1927, 112 Jews lived in Charlottesville. The number dipped to 85 by 1937. The synagogue had trouble gathering a minyan on Friday nights during this period. Enrollment at the religious school hovered between two and ten students in the 1920s and 1930s. Discord erupted in the synagogue over religious ritual in the 1940s. The argument became so heated that one faction of the synagogue changed the building’s locks to the other group out. A fire in 1948 damaged the synagogue roof though Isaac Walters and Harry O’Mansky were able to save the Torah scrolls from destruction. In 1947 the Jewish population slightly increased to 106. Even with this mild growth, the future of Jewish life in Charlottesville seemed so grim by the late 1940s that the Jewish community gave their cemetery to the city of Charlottesville anticipating their imminent extinction.

Despite the influx of Eastern European Jews, Beth Israel remained a Reform congregation, having joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations by 1900. The congregation used an organ, had a choir with Christian members, conducted services in English, and did not require men to wear head coverings, all hallmarks of classical Reform practices. Numbering only 12 contributing members in 1910, Beth Israel soon dropped its UAHC membership, though it rejoined in 1927. By 1930, the congregation had 24 contributing members.

These Reform practices made Charlottesville’s more traditional Eastern European Jewish community uncomfortable, although the community was too small to support a second Jewish congregation. For years, more traditional Jews held separate High Holiday services in the synagogue basement or above the O’Manskys store. In 1931, Morris Massing organized a regular Orthodox service that also met above the O’Manskys store. The group was comprised of U.Va students who Massing would pick up from campus on Friday nights, as well as members of Beth Israel. This informal group lasted until the 1940s and hosted the only bar mitzvah ceremonies in Charlottesville during a 50-year period.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Jewish-owned stores dominated Charlottesville’s downtown. Businesses owned by Levy, Cohen, Eitelman, Zimmerman, and Rosenblock families dotted Charlottesville’s Main Street. During the High Holidays, much of the business district was closed.

The late 1920s had marked the beginning of a period of stagnation and decline in the Jewish community. In 1927, 112 Jews lived in Charlottesville. The number dipped to 85 by 1937. The synagogue had trouble gathering a minyan on Friday nights during this period. Enrollment at the religious school hovered between two and ten students in the 1920s and 1930s. Discord erupted in the synagogue over religious ritual in the 1940s. The argument became so heated that one faction of the synagogue changed the building’s locks to the other group out. A fire in 1948 damaged the synagogue roof though Isaac Walters and Harry O’Mansky were able to save the Torah scrolls from destruction. In 1947 the Jewish population slightly increased to 106. Even with this mild growth, the future of Jewish life in Charlottesville seemed so grim by the late 1940s that the Jewish community gave their cemetery to the city of Charlottesville anticipating their imminent extinction.

UVA's Hillel Center

UVA's Hillel Center

The University of Virginia

The impending end of Charlottesville’s Jewish community was reversed in part by the University of Virginia, which had for years limited the number of Jewish students. Though Thomas Jefferson envisioned a strict distinction between education and religion at the university when he established it in 1819, his vision was ignored by university administrators for much of the early part of the university’s history. When Gratz Cohen, the earliest known Jewish student at U.Va, arrived in 1862 after a stint in the Confederate army, he walked onto a campus with a strong Christian atmosphere. Cohen noted in a letter to his father that he was surrounded by anti-Semitic sentiment. His Jewish faith did not seem to have hindered his career at U.Va as he was elected president of the Jefferson Society. Cohen’s army service probably demonstrated to his classmates his allegiance to the South. Other Jewish U.Va students in the 19th century included Leo Levi and the Oberdorfer twins, A. Leo and Archie.

More Jewish students trickled onto campus in the early 20th century. They were usually excluded from Greek organizations and several Jewish fraternities subsequently popped up. In 1915 Phi Epsilon Pi and Zeta Beta Tau became the university’s first Jewish fraternities. Phi Alpha was formed in 1922 and Alpha Epsilon Pi was established on campus shortly after. A popular activity among Jewish students during the 1920s and 1930s was to eat at the University Delicatessen and Restaurant. Run by a Jewish family, the Yuters, Jewish students flocked to the restaurant for kosher brisket, latkes and other Jewish foods. Keeping kosher was difficult for Jewish students during this era. Kosher meat was imported but often arrived spoiled. Jewish campus life formally organized in 1939 when Rabbi Albert M. Lewis arrived to lead the “Jewish Student Union.” Two years later the Jewish Student Union became part of the national Hillel Network. Rabbi Lewis also served Beth Israel on a part-time basis.

The religious intolerance that Jefferson feared had crept into the university’s official policy by the 1920s. U.Va implemented a quota system to limit the number of Jewish students, especially New York Jews, as children of Jewish immigrants applied to elite colleges in droves. Top institutions such as Columbia, Yale, and Cornell also had quotas for Jewish students in place. U.Va also had very few Jewish faculty members during the first half of the 20th century. Linwood Lehman, a professor of Latin, became the university’s second-ever Jewish faculty member in 1920. He was followed by Ben-Zion Linfield, a professor of mathematics, in 1927. The hiring of Marvin Rosenblum in the Mathematics Department in 1950 marked the beginning of a surge in the number of Jewish faculty.

The impending end of Charlottesville’s Jewish community was reversed in part by the University of Virginia, which had for years limited the number of Jewish students. Though Thomas Jefferson envisioned a strict distinction between education and religion at the university when he established it in 1819, his vision was ignored by university administrators for much of the early part of the university’s history. When Gratz Cohen, the earliest known Jewish student at U.Va, arrived in 1862 after a stint in the Confederate army, he walked onto a campus with a strong Christian atmosphere. Cohen noted in a letter to his father that he was surrounded by anti-Semitic sentiment. His Jewish faith did not seem to have hindered his career at U.Va as he was elected president of the Jefferson Society. Cohen’s army service probably demonstrated to his classmates his allegiance to the South. Other Jewish U.Va students in the 19th century included Leo Levi and the Oberdorfer twins, A. Leo and Archie.

More Jewish students trickled onto campus in the early 20th century. They were usually excluded from Greek organizations and several Jewish fraternities subsequently popped up. In 1915 Phi Epsilon Pi and Zeta Beta Tau became the university’s first Jewish fraternities. Phi Alpha was formed in 1922 and Alpha Epsilon Pi was established on campus shortly after. A popular activity among Jewish students during the 1920s and 1930s was to eat at the University Delicatessen and Restaurant. Run by a Jewish family, the Yuters, Jewish students flocked to the restaurant for kosher brisket, latkes and other Jewish foods. Keeping kosher was difficult for Jewish students during this era. Kosher meat was imported but often arrived spoiled. Jewish campus life formally organized in 1939 when Rabbi Albert M. Lewis arrived to lead the “Jewish Student Union.” Two years later the Jewish Student Union became part of the national Hillel Network. Rabbi Lewis also served Beth Israel on a part-time basis.

The religious intolerance that Jefferson feared had crept into the university’s official policy by the 1920s. U.Va implemented a quota system to limit the number of Jewish students, especially New York Jews, as children of Jewish immigrants applied to elite colleges in droves. Top institutions such as Columbia, Yale, and Cornell also had quotas for Jewish students in place. U.Va also had very few Jewish faculty members during the first half of the 20th century. Linwood Lehman, a professor of Latin, became the university’s second-ever Jewish faculty member in 1920. He was followed by Ben-Zion Linfield, a professor of mathematics, in 1927. The hiring of Marvin Rosenblum in the Mathematics Department in 1950 marked the beginning of a surge in the number of Jewish faculty.

Beth Israel today

Beth Israel today

Anti-Semitism in Charlottesville

Though Jews had been in Charlottesville for nearly 200 years, certain corners of Charlottesville society, such as the elite Farmington Country Club, remained largely closed to the Jewish community until the 1960s. Sol and Mortimer Kaufman, early members of the club, quit after a Jewish friend was denied membership. The anti-Semitic tension bubbling beneath the surface burst forth in 1958 when swastikas were found on the synagogue and on the home of Sam Ruday, a Jewish podiatrist. A message painted onto U.Va’s Cabell Hall in German said “Jews Go Home.” The vandalism was in response to the Richmond chapter of the Anti-Defamation League’s handing out literature advertising a workshop on racial integration sponsored by the NAACP. A random act of anti-Semitism did not deter the University’s Jewish community from letting Civil Rights groups hold meetings at the campus Hillel House.

A Renaissance

Out of the unrest of the civil rights movement emerged a renaissance in the town’s Jewish community. Fueled by the opening up of U.Va to more Jewish faculty and students, the size of the Jewish population swelled beginning in the 1960s and 1970s. Retirees seeking warmer climates began to filter into Charlottesville around the same time. The city’s Jewish population grew to 140 in 1960, and by 1980 it would balloon to 800. By 2001, demographers estimated that 1,500 Jews lived in Charlottesville. The growth in Charlottesville’s Jewish community led Beth Israel to hire a part-time rabbi in the 1960s, purchase a neighboring building for a religious school in 1976, and to hire it first full-time rabbi since the 1880s, Rabbi Sheldon Ezring, in 1979.

Though Jews had been in Charlottesville for nearly 200 years, certain corners of Charlottesville society, such as the elite Farmington Country Club, remained largely closed to the Jewish community until the 1960s. Sol and Mortimer Kaufman, early members of the club, quit after a Jewish friend was denied membership. The anti-Semitic tension bubbling beneath the surface burst forth in 1958 when swastikas were found on the synagogue and on the home of Sam Ruday, a Jewish podiatrist. A message painted onto U.Va’s Cabell Hall in German said “Jews Go Home.” The vandalism was in response to the Richmond chapter of the Anti-Defamation League’s handing out literature advertising a workshop on racial integration sponsored by the NAACP. A random act of anti-Semitism did not deter the University’s Jewish community from letting Civil Rights groups hold meetings at the campus Hillel House.

A Renaissance

Out of the unrest of the civil rights movement emerged a renaissance in the town’s Jewish community. Fueled by the opening up of U.Va to more Jewish faculty and students, the size of the Jewish population swelled beginning in the 1960s and 1970s. Retirees seeking warmer climates began to filter into Charlottesville around the same time. The city’s Jewish population grew to 140 in 1960, and by 1980 it would balloon to 800. By 2001, demographers estimated that 1,500 Jews lived in Charlottesville. The growth in Charlottesville’s Jewish community led Beth Israel to hire a part-time rabbi in the 1960s, purchase a neighboring building for a religious school in 1976, and to hire it first full-time rabbi since the 1880s, Rabbi Sheldon Ezring, in 1979.

The Jewish Community in Charlottesville Today

Interior of Beth Israel's sanctuary

Interior of Beth Israel's sanctuary

Over the past 40 years synagogue membership has swelled from 60 families in 1975 to 380 families in 2013. Before the Great Recession, as many as 410 families attended the congregation. The congregation currently has a preschool and a religious school for its members. Under the leadership of Rabbi Daniel Alexander, who began to serve Beth Israel in 1988, the congregation adopted more traditional styles of prayer, dispensing with the organ and incorporating more Hebrew into their services, while remaining a member of the Union for Reform Judaism.

For much of its history Beth Israel has maintained close ties with U.Va Hillel, often sharing rabbinical services before the congregation hired a full-time rabbi. In 1979, while he was working at U.Va Hillel, Rabbi Alexander established an independent Saturday morning Hebrew minyan that alternated between Hillel and the synagogue. The minyan followed Alexander when he became the rabbi at Beth Israel in 1988. A havurah, an informal group, meets twice a month on Shabbat at U.Va’s Hillel.

The current climate for Jewish life at the University of Virginia differs starkly from the environment Gratz Cohen encountered in the 1860s. Today about ten percent of the university’s undergraduates, approximately 1,400 students, are Jewish. A professorship in Jewish studies was established in the mid-1980s and today there is a thriving Jewish Studies program. In addition to the Hillel, a Chabad House opened near campus in 2002.

Today, the Charlottesville Jewish community is primarily made up of professionals affiliated with the University of Virginia and the UVa Health System. Other new Jewish families have arrived to work as professionals or to enjoy the town’s lovely quality of life. Once in serious danger of extinction, the Jewish community of Charlottesville is primed for a bright future.

For much of its history Beth Israel has maintained close ties with U.Va Hillel, often sharing rabbinical services before the congregation hired a full-time rabbi. In 1979, while he was working at U.Va Hillel, Rabbi Alexander established an independent Saturday morning Hebrew minyan that alternated between Hillel and the synagogue. The minyan followed Alexander when he became the rabbi at Beth Israel in 1988. A havurah, an informal group, meets twice a month on Shabbat at U.Va’s Hillel.

The current climate for Jewish life at the University of Virginia differs starkly from the environment Gratz Cohen encountered in the 1860s. Today about ten percent of the university’s undergraduates, approximately 1,400 students, are Jewish. A professorship in Jewish studies was established in the mid-1980s and today there is a thriving Jewish Studies program. In addition to the Hillel, a Chabad House opened near campus in 2002.

Today, the Charlottesville Jewish community is primarily made up of professionals affiliated with the University of Virginia and the UVa Health System. Other new Jewish families have arrived to work as professionals or to enjoy the town’s lovely quality of life. Once in serious danger of extinction, the Jewish community of Charlottesville is primed for a bright future.

Sources

Hantman, Jeffrey and Phyllis Leffler. The exhibit “To Seek the Peace of the City: Jewish Life in Charlottesville."