Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Danville, Virginia

Danville: Historical Overview

|

Before Danville became the “World’s Best Tobacco Market” and a major textile hub, it was a quiet border town where Revolutionary War veterans would gather every year to fish and reminisce. The region was formally settled in 1746 when William Wynne established a ferry crossing named Wynne’s Falls. The town was renamed Danville in 1793 as tobacco became an important part of the local economy. The completion of the Richmond and Danville Railroad in 1856 accelerated the development of the tobacco industry and made the town a crucial transport hub during the Civil War.

Danville has been home to a small Jewish community for over a century. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Danville

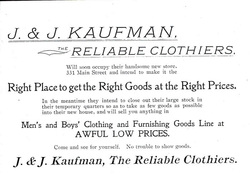

Ad for J & J Kaufman, 1898

Ad for J & J Kaufman, 1898

Early Settlers

Tobacco drove Danville’s growth when the first Jewish settlers arrived following the Civil War. Bavarian born Jonas Kaufman opened Danville’s first Jewish-owned store, J&J Kaufman, in 1866. The men’s and boy’s clothing store would quickly become one of Danville’s most respected retail houses. By 1878, 68 Jews lived in Danville; three years later, ten Jewish-owned businesses were listed in Danville’s 1881 city directory. Jacob Hyman, Albert and Lewis Wildman, Theodore Greenwald, S. Hirsch, Jacob Brafman, and Jonas Kaufman all had clothing stores. D.S. Lisberger and Abram Isaacs were partners in a dry goods store, while Louis Fleishman also owned a dry goods business. Louis Goldman had a jewelry store and Leon Strauss was a tobacco dealer. Most of these early Jewish residents were immigrants from the German states. The growth of the Jewish community prompted the creation of a B’nai B’rith chapter in 1879. Lisberger was the Randolph Lodge’s first president. By 1885 the chapter was meeting twice a month at the Odd Fellows’ Hall on Main Street. B’nai B’rith organized religious services before a formal congregation was established.

The opening of the Riverside Cotton Mills in 1882, which would evolve into Dan River Inc., the largest textile mill in the world by the mid-20th century, marked the beginning of Danville’s rise as a textile power. As the mills gained economic might and the tobacco industry continued to be a strong commercial force, a growing number of Jews from Eastern and Central Europe arrived in Danville. New Jewish merchants appeared by the publication of the 1892 city directory, such as Max Koplen, Isaac Roman, and Kolman Silverman. They all owned clothing stores. Jacob Berman came to Danville in 1894 for what he thought he was a quick lunch break during his trip to Milton, North Carolina. Berman planned to open a clothing store in Milton, but after meeting Harry Wooding he skipped his train. Wooding, who later became Danville’s mayor, promised Berman a free first month of rent on a downtown building, and Berman decided to open his store, J. Berman, Men’s Clothier, in Danville.

Tobacco drove Danville’s growth when the first Jewish settlers arrived following the Civil War. Bavarian born Jonas Kaufman opened Danville’s first Jewish-owned store, J&J Kaufman, in 1866. The men’s and boy’s clothing store would quickly become one of Danville’s most respected retail houses. By 1878, 68 Jews lived in Danville; three years later, ten Jewish-owned businesses were listed in Danville’s 1881 city directory. Jacob Hyman, Albert and Lewis Wildman, Theodore Greenwald, S. Hirsch, Jacob Brafman, and Jonas Kaufman all had clothing stores. D.S. Lisberger and Abram Isaacs were partners in a dry goods store, while Louis Fleishman also owned a dry goods business. Louis Goldman had a jewelry store and Leon Strauss was a tobacco dealer. Most of these early Jewish residents were immigrants from the German states. The growth of the Jewish community prompted the creation of a B’nai B’rith chapter in 1879. Lisberger was the Randolph Lodge’s first president. By 1885 the chapter was meeting twice a month at the Odd Fellows’ Hall on Main Street. B’nai B’rith organized religious services before a formal congregation was established.

The opening of the Riverside Cotton Mills in 1882, which would evolve into Dan River Inc., the largest textile mill in the world by the mid-20th century, marked the beginning of Danville’s rise as a textile power. As the mills gained economic might and the tobacco industry continued to be a strong commercial force, a growing number of Jews from Eastern and Central Europe arrived in Danville. New Jewish merchants appeared by the publication of the 1892 city directory, such as Max Koplen, Isaac Roman, and Kolman Silverman. They all owned clothing stores. Jacob Berman came to Danville in 1894 for what he thought he was a quick lunch break during his trip to Milton, North Carolina. Berman planned to open a clothing store in Milton, but after meeting Harry Wooding he skipped his train. Wooding, who later became Danville’s mayor, promised Berman a free first month of rent on a downtown building, and Berman decided to open his store, J. Berman, Men’s Clothier, in Danville.

Temple Beth Sholom

Temple Beth Sholom

Organized Jewish Life in Danville

As more Jews arrived in the 1890s, they established formal congregations. Temple Beth Sholom, Danville’s Reform congregation, was born in the upstairs stock room of Louis Herman’s clothing store. At first, Herman led an informal religious school in the room, which was nicknamed “Herman’s Hall.” On October 28, 1893, a group of Danville Jews founded Beth Sholom there and elected David Macks, Isaac Rosenstock, and Matthew Hessberg as officers of the new congregation. Beth Sholom later met in a rented room over Hagan’s Drug Store before its synagogue at 129 Sutherlin Avenue was completed in 1900. Local churches helped fund the construction of the striking, red brick synagogue, where the congregation still worships today.

Danville’s Orthodox Jews began to pray together in the 1890s, usually meeting in rooms above people’s stores. By 1904, they had established Agudas Achim. Although the congregation was small, numbering 19 members in 1907, they had full-time spiritual leaders, including Elias Phillips in 1904, J.P. Berson in 1906, and J.H. Battersen in 1907. They even acquired a house at 407 Linn Street, which served as a synagogue and home for the rabbi. Kolman Silverman was president of Agudas Achim in 1907.

Agudas Achim remained active until 1908, when it was no longer listed in the Danville City Directory. In 1909, Danville’s Orthodox community established a new congregation, named Aetz Chayim. The new congregation’s trustees, including Kolman Silverman, Harry Meyers, Jacob Greenberg and Morris Bailin, soon purchased land for a synagogue. The building, located at 728 Wilson Avenue, was completed in 1910. Rabbi David Kushner, an immigrant from Lithuania, served as Aetz Chayim’s first rabbi. Trained at the famed Vilna Yeshiva, Kushner had previously served as the rabbi in Petersburg before coming to Danville in 1909. While he left Aetz Chayim in 1912, he remained in Danville, opening a store. In addition, he served a small Orthodox congregation in nearby South Boston, Virginia, for 40 years.

As more Jews arrived in the 1890s, they established formal congregations. Temple Beth Sholom, Danville’s Reform congregation, was born in the upstairs stock room of Louis Herman’s clothing store. At first, Herman led an informal religious school in the room, which was nicknamed “Herman’s Hall.” On October 28, 1893, a group of Danville Jews founded Beth Sholom there and elected David Macks, Isaac Rosenstock, and Matthew Hessberg as officers of the new congregation. Beth Sholom later met in a rented room over Hagan’s Drug Store before its synagogue at 129 Sutherlin Avenue was completed in 1900. Local churches helped fund the construction of the striking, red brick synagogue, where the congregation still worships today.

Danville’s Orthodox Jews began to pray together in the 1890s, usually meeting in rooms above people’s stores. By 1904, they had established Agudas Achim. Although the congregation was small, numbering 19 members in 1907, they had full-time spiritual leaders, including Elias Phillips in 1904, J.P. Berson in 1906, and J.H. Battersen in 1907. They even acquired a house at 407 Linn Street, which served as a synagogue and home for the rabbi. Kolman Silverman was president of Agudas Achim in 1907.

Agudas Achim remained active until 1908, when it was no longer listed in the Danville City Directory. In 1909, Danville’s Orthodox community established a new congregation, named Aetz Chayim. The new congregation’s trustees, including Kolman Silverman, Harry Meyers, Jacob Greenberg and Morris Bailin, soon purchased land for a synagogue. The building, located at 728 Wilson Avenue, was completed in 1910. Rabbi David Kushner, an immigrant from Lithuania, served as Aetz Chayim’s first rabbi. Trained at the famed Vilna Yeshiva, Kushner had previously served as the rabbi in Petersburg before coming to Danville in 1909. While he left Aetz Chayim in 1912, he remained in Danville, opening a store. In addition, he served a small Orthodox congregation in nearby South Boston, Virginia, for 40 years.

Aetz Chayim

Aetz Chayim

Danville’s small Jewish community was divided. Only 114 Jews lived in Danville in 1907. Similarly sized Jewish communities in Lynchburg and Harrisonburg had only one congregation, while Danville had two tiny ones: Agudas Achim had 19 members in 1907, while Beth Sholom had only nine. Each Danville congregation established its own cemetery. Temple Beth Sholom bought land within Green Hill Cemetery while Aetz Chayim built its own cemetery on Westover Drive. The congregations were able to remain financially viable in their early years because of the generosity of the town’s Jewish merchant families. Louis Herman supported Beth Sholom while Isaac Schuster helped sustain Aetz Chayim. Both owned prominent department stores in Danville. Herman was the president of Beth Sholom for 43 years. These divisions even cut across families. Though they were brothers and business partners, Ike Berman was president of Aetz Chayim while Louis Berman was president at Temple Beth Sholom. Herman Kushner was a member of Aetz Chayim while his brothers Benjamin and Samuel were vice president and president of Temple Beth Sholom.

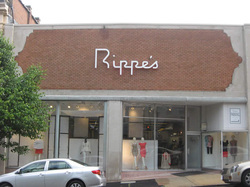

Rippe's remains in business today

Rippe's remains in business today

The Community Grows

By 1917, the number of Jewish retailers had mushroomed to 30. Most of the Jewish owned businesses at the time were clothing or dry good stores. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Main Street was lined with Jewish-owned businesses. Long established stores like L. Herman Department Store, J. Berman, and J &J Kaufman were joined by relatively newer stores such as Rippe’s and Harnsberger’s Department Store. Benjamin Rippe and his wife Annie left New York and came to Danville in 1907 and opened up Rippe’s, a women’s clothing store. Born in Lindheim, Germany, Isaac Schuster came to Danville from Newport, Rhode Island around 1910 as a business partner in Harnsberger’s Department Store. Schuster eventually bought out his non-Jewish business partners and expanded the store all the way to Patton Street. Aside from retail, Jews were also opticians, music teachers, tailors, and lawyers. By 1927, 180 Jews lived in Danville. A large portion of Danville’s Jewish community lived near Aetz Chayim. The area around Wilson Street came to be known as “Kugel Street” because of the many Jewish families that lived in the area. Kugel Street resident Joe Hordish was known for walking down Wilson Street shouting “minyan!” around the time of prayers. Jewish families began moving out of the area by the 1940s.

By 1917, the number of Jewish retailers had mushroomed to 30. Most of the Jewish owned businesses at the time were clothing or dry good stores. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Main Street was lined with Jewish-owned businesses. Long established stores like L. Herman Department Store, J. Berman, and J &J Kaufman were joined by relatively newer stores such as Rippe’s and Harnsberger’s Department Store. Benjamin Rippe and his wife Annie left New York and came to Danville in 1907 and opened up Rippe’s, a women’s clothing store. Born in Lindheim, Germany, Isaac Schuster came to Danville from Newport, Rhode Island around 1910 as a business partner in Harnsberger’s Department Store. Schuster eventually bought out his non-Jewish business partners and expanded the store all the way to Patton Street. Aside from retail, Jews were also opticians, music teachers, tailors, and lawyers. By 1927, 180 Jews lived in Danville. A large portion of Danville’s Jewish community lived near Aetz Chayim. The area around Wilson Street came to be known as “Kugel Street” because of the many Jewish families that lived in the area. Kugel Street resident Joe Hordish was known for walking down Wilson Street shouting “minyan!” around the time of prayers. Jewish families began moving out of the area by the 1940s.

Discrimination

While Jews in Danville never faced harsh anti-Semitism, they did sometimes experience discrimination. Restrictive covenants barred Jews, Syrians, and Greeks from owning real estate in certain neighborhoods in the 1920s and 1930s. When the Beaverstone Park neighborhood opened after World War II, Jews were not welcome in the new development. Also, during the High Holidays, Jewish students were not excused from school and were penalized one-third of a grade each day they were gone. In the 1940s, Victor Lobl and Rabbi Max Kapustin of Aetz Chayim challenged the Danville School Board in court and eventually won a ruling that Jewish students could not be punished for observing religious holidays.

While Jews in Danville never faced harsh anti-Semitism, they did sometimes experience discrimination. Restrictive covenants barred Jews, Syrians, and Greeks from owning real estate in certain neighborhoods in the 1920s and 1930s. When the Beaverstone Park neighborhood opened after World War II, Jews were not welcome in the new development. Also, during the High Holidays, Jewish students were not excused from school and were penalized one-third of a grade each day they were gone. In the 1940s, Victor Lobl and Rabbi Max Kapustin of Aetz Chayim challenged the Danville School Board in court and eventually won a ruling that Jewish students could not be punished for observing religious holidays.

The 1930s and 1940s

As the Great Depression crushed the nation’s economy, it leveled the finances of Danville’s Jewish institutions. Aetz Chayim was no longer able to afford a rabbi as the congregation shrunk. The members only used the main sanctuary of their synagogue on the High Holidays. They even merged religious schools with Beth Sholom. By the end of the 1930s, Aetz Chayim had recovered its footing, and was once again able to employ a rabbi. Rabbi Max Kapustin left Germany in 1938 and, with the help of Isaac Schuster, become the rabbi of Aetz Chayim. Kapustin, who had recently received a Ph.D. in Semitic languages from Heidelberg University, revived the synagogue’s religious education program. He taught Hebrew twice a week after school, religious school after Saturday services, and Jewish history on Sundays. After ten years in Danville, Rabbi Kapustin left Aetz Chayim in 1948 to become a professor of Semitic languages and the Hillel Director at Wayne State University.

During its early years, Beth Sholom was too small to have a rabbi. Julius Kaufman usually served as lay leader for services. In 1935, the Reform congregation hired Julius Gutmann as its first full-time rabbi. Beth Sholom’s membership surged following World War II as several families left Aetz Chayim to join the Reform congregation. A wing for the religious school was later built in the 1950s to accommodate the growth. The congregation formally joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1944, although Beth Sholom had been a classical Reform congregation since its inception. Rabbi Guttmann left in 1945 and was followed by a series of short-termed rabbis, including Arnold Shevlin who led Beth Sholom from 1952 to 1958. After Shevlin’s departure, Rabbi Benjamin Kelson came to Beth Sholom and remained until 1972.

Zionism was a controversial issue within the Reform movement in the 1940s, which also touched Danville. In 1943, 90 rabbis and lay leaders formed the Council for American Judaism in protest to the Central Conference of American Rabbis’ passing a resolution that supported the formation of a Jewish army in Palestine. The council believed that the push for an independent Jewish state would cause confusion amongst Diaspora Jewry about their identity in their respective countries. Congregation Beth Israel in Houston required new congregants to sign an oath against Zionism in order to get full membership starting in 1943, while B’nai Israel in Baton Rouge wrote an anti-Zionist clause into its constitution in 1945, which led to an eventual split in the congregation. Danville’s Beth Sholom never went to such extreme measures, though it did prohibit local Zionist organizations from using the temple. Beth Sholom’s board also insisted that the rabbi not promote Zionism from the pulpit. In February 1946, Dr. Samuel Newman, a prominent local physician, ardent Zionist, and member of Aetz Chayim, wrote a letter to Beth Sholom’s board condemning their decision to ban Zionist organizations from meeting in the temple.

As the debate about Zionism raged in the Danville Jewish community, 18-year-old Ralph Lowenstein, who had grown up at Aetz Chayim, decided to join the fight to establish the Jewish state. After his freshman year at Columbia University in 1948, Lowenstein volunteered for the Israeli army without telling his family. Lowenstein was one of only a few Jews from the South to join the Israeli military. Later, he returned to the United States and eventually became the dean of the College of Journalism and Communications at the University of Florida.

As the Great Depression crushed the nation’s economy, it leveled the finances of Danville’s Jewish institutions. Aetz Chayim was no longer able to afford a rabbi as the congregation shrunk. The members only used the main sanctuary of their synagogue on the High Holidays. They even merged religious schools with Beth Sholom. By the end of the 1930s, Aetz Chayim had recovered its footing, and was once again able to employ a rabbi. Rabbi Max Kapustin left Germany in 1938 and, with the help of Isaac Schuster, become the rabbi of Aetz Chayim. Kapustin, who had recently received a Ph.D. in Semitic languages from Heidelberg University, revived the synagogue’s religious education program. He taught Hebrew twice a week after school, religious school after Saturday services, and Jewish history on Sundays. After ten years in Danville, Rabbi Kapustin left Aetz Chayim in 1948 to become a professor of Semitic languages and the Hillel Director at Wayne State University.

During its early years, Beth Sholom was too small to have a rabbi. Julius Kaufman usually served as lay leader for services. In 1935, the Reform congregation hired Julius Gutmann as its first full-time rabbi. Beth Sholom’s membership surged following World War II as several families left Aetz Chayim to join the Reform congregation. A wing for the religious school was later built in the 1950s to accommodate the growth. The congregation formally joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1944, although Beth Sholom had been a classical Reform congregation since its inception. Rabbi Guttmann left in 1945 and was followed by a series of short-termed rabbis, including Arnold Shevlin who led Beth Sholom from 1952 to 1958. After Shevlin’s departure, Rabbi Benjamin Kelson came to Beth Sholom and remained until 1972.

Zionism was a controversial issue within the Reform movement in the 1940s, which also touched Danville. In 1943, 90 rabbis and lay leaders formed the Council for American Judaism in protest to the Central Conference of American Rabbis’ passing a resolution that supported the formation of a Jewish army in Palestine. The council believed that the push for an independent Jewish state would cause confusion amongst Diaspora Jewry about their identity in their respective countries. Congregation Beth Israel in Houston required new congregants to sign an oath against Zionism in order to get full membership starting in 1943, while B’nai Israel in Baton Rouge wrote an anti-Zionist clause into its constitution in 1945, which led to an eventual split in the congregation. Danville’s Beth Sholom never went to such extreme measures, though it did prohibit local Zionist organizations from using the temple. Beth Sholom’s board also insisted that the rabbi not promote Zionism from the pulpit. In February 1946, Dr. Samuel Newman, a prominent local physician, ardent Zionist, and member of Aetz Chayim, wrote a letter to Beth Sholom’s board condemning their decision to ban Zionist organizations from meeting in the temple.

As the debate about Zionism raged in the Danville Jewish community, 18-year-old Ralph Lowenstein, who had grown up at Aetz Chayim, decided to join the fight to establish the Jewish state. After his freshman year at Columbia University in 1948, Lowenstein volunteered for the Israeli army without telling his family. Lowenstein was one of only a few Jews from the South to join the Israeli military. Later, he returned to the United States and eventually became the dean of the College of Journalism and Communications at the University of Florida.

After World War II

After World War II, Danville Jews remained concentrated in the retail business. Ben and Bec Davidowitz came to Danville in 1955 so Ben could manage the Jewel Box jewelry store. They originally thought Danville would be a brief stop in Ben’s career, but in 1959, they opened Ben David Jewelers, which remains one of Danville’s largest jewelry stores today. Long standing Jewish-owned clothing stores like Rippe’s, M. Koplen, J & J Kaufman, and Silverman’s continued to flourish during the post-war years.

The civil rights era in Danville, like in many Southern communities, was a tense and difficult period. On May 31, 1963, civil rights activists led the first in a series of marches and demonstrations in Danville aimed at increasing African American involvement in municipal affairs. After a demonstration on June 6, Judge Archibald Aiken Jr., indicted three leaders for “conspiring to incite the colored population of the State to acts of violence and war against the white population,” a statute created after John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859. Racial tensions erupted weeks later when police and garbage men attacked African American citizens with night sticks and sprayed fire hoses at them at a vigil for imprisoned activists. Court cases against demonstrators from the 1963 demonstrations lingered until 1973, and public schools were not fully integrated until 1970.

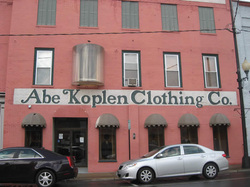

Albert Koplen stood out among downtown merchants for his active support of African American civil rights. His store, Abe Koplen Clothing Company, was one of the few stores not to be boycotted during the civil rights era. Koplen was also one of the first store owners in town to hire black sales staff. Koplen remained active in Danville civic life until his death in 2011. He was president of the Downtown Merchants Association, a founding member of the Tuscarora Golf Club, and an executive director of the Israel Bond Drive. Other Danville Jews also took on civic leadership roles. Samuel Kushner, an attorney, was the president of the Danville Bar Association. His son, Samuel Kushner, Jr., was on the Danville city council for ten years before serving as mayor for two years.

After World War II, Danville Jews remained concentrated in the retail business. Ben and Bec Davidowitz came to Danville in 1955 so Ben could manage the Jewel Box jewelry store. They originally thought Danville would be a brief stop in Ben’s career, but in 1959, they opened Ben David Jewelers, which remains one of Danville’s largest jewelry stores today. Long standing Jewish-owned clothing stores like Rippe’s, M. Koplen, J & J Kaufman, and Silverman’s continued to flourish during the post-war years.

The civil rights era in Danville, like in many Southern communities, was a tense and difficult period. On May 31, 1963, civil rights activists led the first in a series of marches and demonstrations in Danville aimed at increasing African American involvement in municipal affairs. After a demonstration on June 6, Judge Archibald Aiken Jr., indicted three leaders for “conspiring to incite the colored population of the State to acts of violence and war against the white population,” a statute created after John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859. Racial tensions erupted weeks later when police and garbage men attacked African American citizens with night sticks and sprayed fire hoses at them at a vigil for imprisoned activists. Court cases against demonstrators from the 1963 demonstrations lingered until 1973, and public schools were not fully integrated until 1970.

Albert Koplen stood out among downtown merchants for his active support of African American civil rights. His store, Abe Koplen Clothing Company, was one of the few stores not to be boycotted during the civil rights era. Koplen was also one of the first store owners in town to hire black sales staff. Koplen remained active in Danville civic life until his death in 2011. He was president of the Downtown Merchants Association, a founding member of the Tuscarora Golf Club, and an executive director of the Israel Bond Drive. Other Danville Jews also took on civic leadership roles. Samuel Kushner, an attorney, was the president of the Danville Bar Association. His son, Samuel Kushner, Jr., was on the Danville city council for ten years before serving as mayor for two years.

Beth Sholom's sanctuary features a

Beth Sholom's sanctuary features a stained glass window depicting Moses

The Community Declines

By 1960, Danville’s Jewish community had reached a peak of 245 people. Both congregations remained fairly small, though each managed to maintain a full-time rabbi. Beth Sholom never grew larger than the 45 contributing members it had in 1962, while Aetz Chayim began to shrink as many children raised in the congregation moved away, often to Baltimore. By the 1980s, with its membership numbers dwindling, Aetz Chayim, still led by a full-time rabbi, could no longer maintain its aging synagogue. Rather than sell the building, they decided to tear it down in 1986. Afterward, the remaining members of the congregation met in private homes, before Aetz Chayim finally dissolved by the end of the decade.

The small Danville Jewish community remained divided up through the dissolution of Aetz Chayim. Some Orthodox members of Aetz Chayim would not enter Beth Sholom because of stained glass windows in the temple’s main sanctuary that depicted Moses receiving the Ten Commandments, interpreted by some as a graven image. When Aetz Chayim was demolished, none of the building’s artifacts or Judaica were offered to Beth Sholom. Despite their religious differences, the Danville Jewish community came together in such organizations as Hadassah, B’nai B’rith, and Young Judea.

By 1960, Danville’s Jewish community had reached a peak of 245 people. Both congregations remained fairly small, though each managed to maintain a full-time rabbi. Beth Sholom never grew larger than the 45 contributing members it had in 1962, while Aetz Chayim began to shrink as many children raised in the congregation moved away, often to Baltimore. By the 1980s, with its membership numbers dwindling, Aetz Chayim, still led by a full-time rabbi, could no longer maintain its aging synagogue. Rather than sell the building, they decided to tear it down in 1986. Afterward, the remaining members of the congregation met in private homes, before Aetz Chayim finally dissolved by the end of the decade.

The small Danville Jewish community remained divided up through the dissolution of Aetz Chayim. Some Orthodox members of Aetz Chayim would not enter Beth Sholom because of stained glass windows in the temple’s main sanctuary that depicted Moses receiving the Ten Commandments, interpreted by some as a graven image. When Aetz Chayim was demolished, none of the building’s artifacts or Judaica were offered to Beth Sholom. Despite their religious differences, the Danville Jewish community came together in such organizations as Hadassah, B’nai B’rith, and Young Judea.

The Jewish Community in Danville Today

Danville’s Jewish population began declining in the 1970s and stands at about 60 today. Over the past 50 years, the town’s economy has been hit hard by the closing of the textile mills and the decline of the local tobacco industry. While many Jewish-owned stores have closed in recent decades, Rippe’s, the Abe Koplen Clothing Company, and Ben David Jewelers remain in operation, run by their founders’ descendants.

Even as the Jewish population has shrunk in recent decades, Beth Sholom has remained active. Rabbi Larry Kaplan led the congregation during the 1970s, while Alan Ponn served as Beth Sholom’s last full-time rabbi until he left in 1988. Since then, the congregation has relied on lay leaders and visiting rabbis to lead services. Peter and Jo Ann Howard, who moved to Danville in 1973, have become leaders of the Reform congregation. Both have served as president, while Jo Ann currently serves as lay leader, president, and religious school director. In 2013, the congregation had 28 households. A visiting rabbi conducts services every few weeks. Though Danville’s community is small and does not have many young families, the remaining Jews are committed to preserving a Jewish presence in Danville for as long as they can.

Even as the Jewish population has shrunk in recent decades, Beth Sholom has remained active. Rabbi Larry Kaplan led the congregation during the 1970s, while Alan Ponn served as Beth Sholom’s last full-time rabbi until he left in 1988. Since then, the congregation has relied on lay leaders and visiting rabbis to lead services. Peter and Jo Ann Howard, who moved to Danville in 1973, have become leaders of the Reform congregation. Both have served as president, while Jo Ann currently serves as lay leader, president, and religious school director. In 2013, the congregation had 28 households. A visiting rabbi conducts services every few weeks. Though Danville’s community is small and does not have many young families, the remaining Jews are committed to preserving a Jewish presence in Danville for as long as they can.