Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Fredericksburg, Virginia

Historical Overview

|

Located at the fall line of the Rappahannock River and nearly equidistant from Washington D.C. and Richmond, Fredericksburg, Virginia, was incorporated as a town in 1781. Thomas Jefferson drafted one of the United States’ foundational documents in Fredericksburg, the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which provided a template for the constitution’s first amendment. This document established that Jews could practice their religion freely and helped guarantee the future of Judaism in America.

Jews have lived in Fredericksburg since before the American Revolution, and Fredericksburg has been home to a Jewish community for well over a century. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Fredericksburg

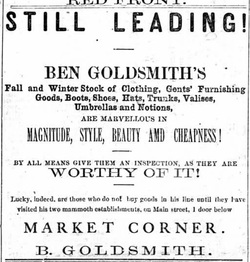

Ad for Ben Goldsmith's store, 1882

Ad for Ben Goldsmith's store, 1882

Early Settlers

A few scattered Jews lived in Fredericksburg during 18th century, though little is known about them. Joseph Myers managed interests in Fredericksburg during the American Revolution for the Gratz Brothers, who were purchasing agents for the Virginia Board of Trade. The name Hezekiah Levy is listed in records from Masonic Lodge #4 of Fredericksburg around 1776. There is record of a Levi family living in nearby King George, Virginia, in 1817. A history of 19th century Fredericksburg, published in 1898, refers to Isaac Jones, who appears in town census records as early as 1820, as “Jew” Jones. Although there were Jews living in the Fredericksburg area as far back as the 18th century, they did not begin to form a community until the 1860s.

Several Prussian Jewish families came to Fredericksburg during the 1850s and opened mercantile stores. The Hirsh family emigrated from Baden, Prussia to America around 1850. During the 1850s, Kaufman Hirsh peddled in rural towns west of Fredericksburg such as Unionville and Verdiersville. Kaufman’s sons Isaac and Simon lived in downtown Fredericksburg by the time of 1860 Census and the rest of the family joined them soon after. In 1861, Isaac joined the 30th Regiment of Virginia, while his house was used as a hospital during the war. The turmoil of the war years affected Fredericksburg’s small Jewish population. David Hirsh, younger brother of Isaac and Simon, later recalled that he and his parents hid in their cellar while the Union army shelled the town during the Battle of Fredericksburg. Local merchants like Benjamin Goldsmith, whose stores had been looted by soldiers, filed claims with Fredericksburg’s Circuit Court for damages.

After the war, Isaac and Simon Hirsh opened their own mercantile store in 1867. Simon left to join his father’s business in 1870, but Isaac continued to operate the store with his wife Hanna. By 1884, the store had a ladies’ dry goods department, a hat department overseen by Hanna, and a department with carpets, mattings, and other fabric goods. In 1884, the Fredericksburg Star published profiles of the city’s leading businesses and wrote about Isaac Hirsh’s store, “the establishment is one worthy of almost unlimited praise and confidence.” Isaac was elected to the City Council in 1881 and again in 1884. In 1890, he was appointed president of the Fredericksburg Manufacturing Company, which was created to promote the town’s industry and economic growth. He also served on the local school board.

Simon and David Hirsh started Simon Hirsch & Bro. in 1870, which sold farm produce like eggs, fruit, and animal hides as well as scrap metal, much of it left over from the Civil War battles that took place in Fredericksburg. The business did quite well as Simon bought a gold mine in 1878, and David joined the local boat club. Simon also served as president of the Fredericksburg Volunteer Fire Department. After Simon died in the mid-1880s, David continued to operate the business for many more years.

Other Jewish merchants established themselves in Fredericksburg in the years after the Civil War. Benjamin Goldsmith moved to town from New Bern, North Carolina, and opened a men’s clothing store in 1861. In 1865, he married Caroline Hirsh, daughter of Kaufman and Hannah Hirsh, in Fredericksburg’s first Jewish wedding. M. J. Michelbacher, the first rabbi at Richmond’s Congregation Beth Ahabah, officiated at the ceremony. His business thrived after the war as Goldsmith had the largest department store in the city by 1873. Henry Millhouser and Leopold Fleischer were merchants in Fredericksburg by the 1870s. Joseph Hable opened a clothing store in 1877. B.H. Jacobs was another successful dry goods merchant in Fredericksburg. Henry Ulman opened Ulman Brothers in 1884, which sold beer and cigars, among other things. Adolph Loewenson started Loewenson’s Jewelry Store in 1892 and was known for his handmade clocks. He sold the business in 1906 to Sydney Kaufman, who managed it until he died in 1956.

A few scattered Jews lived in Fredericksburg during 18th century, though little is known about them. Joseph Myers managed interests in Fredericksburg during the American Revolution for the Gratz Brothers, who were purchasing agents for the Virginia Board of Trade. The name Hezekiah Levy is listed in records from Masonic Lodge #4 of Fredericksburg around 1776. There is record of a Levi family living in nearby King George, Virginia, in 1817. A history of 19th century Fredericksburg, published in 1898, refers to Isaac Jones, who appears in town census records as early as 1820, as “Jew” Jones. Although there were Jews living in the Fredericksburg area as far back as the 18th century, they did not begin to form a community until the 1860s.

Several Prussian Jewish families came to Fredericksburg during the 1850s and opened mercantile stores. The Hirsh family emigrated from Baden, Prussia to America around 1850. During the 1850s, Kaufman Hirsh peddled in rural towns west of Fredericksburg such as Unionville and Verdiersville. Kaufman’s sons Isaac and Simon lived in downtown Fredericksburg by the time of 1860 Census and the rest of the family joined them soon after. In 1861, Isaac joined the 30th Regiment of Virginia, while his house was used as a hospital during the war. The turmoil of the war years affected Fredericksburg’s small Jewish population. David Hirsh, younger brother of Isaac and Simon, later recalled that he and his parents hid in their cellar while the Union army shelled the town during the Battle of Fredericksburg. Local merchants like Benjamin Goldsmith, whose stores had been looted by soldiers, filed claims with Fredericksburg’s Circuit Court for damages.

After the war, Isaac and Simon Hirsh opened their own mercantile store in 1867. Simon left to join his father’s business in 1870, but Isaac continued to operate the store with his wife Hanna. By 1884, the store had a ladies’ dry goods department, a hat department overseen by Hanna, and a department with carpets, mattings, and other fabric goods. In 1884, the Fredericksburg Star published profiles of the city’s leading businesses and wrote about Isaac Hirsh’s store, “the establishment is one worthy of almost unlimited praise and confidence.” Isaac was elected to the City Council in 1881 and again in 1884. In 1890, he was appointed president of the Fredericksburg Manufacturing Company, which was created to promote the town’s industry and economic growth. He also served on the local school board.

Simon and David Hirsh started Simon Hirsch & Bro. in 1870, which sold farm produce like eggs, fruit, and animal hides as well as scrap metal, much of it left over from the Civil War battles that took place in Fredericksburg. The business did quite well as Simon bought a gold mine in 1878, and David joined the local boat club. Simon also served as president of the Fredericksburg Volunteer Fire Department. After Simon died in the mid-1880s, David continued to operate the business for many more years.

Other Jewish merchants established themselves in Fredericksburg in the years after the Civil War. Benjamin Goldsmith moved to town from New Bern, North Carolina, and opened a men’s clothing store in 1861. In 1865, he married Caroline Hirsh, daughter of Kaufman and Hannah Hirsh, in Fredericksburg’s first Jewish wedding. M. J. Michelbacher, the first rabbi at Richmond’s Congregation Beth Ahabah, officiated at the ceremony. His business thrived after the war as Goldsmith had the largest department store in the city by 1873. Henry Millhouser and Leopold Fleischer were merchants in Fredericksburg by the 1870s. Joseph Hable opened a clothing store in 1877. B.H. Jacobs was another successful dry goods merchant in Fredericksburg. Henry Ulman opened Ulman Brothers in 1884, which sold beer and cigars, among other things. Adolph Loewenson started Loewenson’s Jewelry Store in 1892 and was known for his handmade clocks. He sold the business in 1906 to Sydney Kaufman, who managed it until he died in 1956.

Beth Sholom's first synagogue

Beth Sholom's first synagogue

Jewish Life in Fredericksburg

In 1877, Fredericksburg Jews established the Hebrew Benevolent Society and elected Isaac Hirsh as its first president. According to a brief article in the local newspaper six months later, “the association…has relieved the necessities of a good many poor that have applied to them for relief.” Thirty years later, the society, now named the Hebrew Relief Association but still led by Isaac Hirsh, remained active, though it only had 12 members and $36 in annual income. It did not function as a religious congregation, though Fredericksburg Jews did hold High Holiday services at the time. An estimated 60 Jews lived in Fredericksburg in 1907. By 1919, the Jewish community remained small, with 66 people, and the Hebrew Relief Association, now led by Isaac Hirsh’s son Maurice, was still the city’s only Jewish organization.

The Fredericksburg Jewish community consisted of only a handful of families, though they set down roots in the city. Several children of Fredericksburg’s first Jewish immigrants inherited family businesses or opened their own enterprises. David Hirsh’s son, whom he named Simon in honor of his brother, joined his father at the feed store after serving in the Navy. Simon managed the business for many years though it closed after he died in 1959. Joseph and Jacob Goldsmith helped their father Benjamin at B. Goldsmith & Son although Jacob opened the Opera House Saloon in 1898, one of Fredericksburg’s finest restaurants at the time. Joseph partnered with his father in 1902 and worked in the family business until he died in 1957; together, Benjamin and Joseph Goldsmith combined to manage the store for 96 years. Sydney Kaufman, son of Herman Kaufman, bought control of Loewenson’s Jewelry store in 1906 and managed it until he died in 1956

In 1877, Fredericksburg Jews established the Hebrew Benevolent Society and elected Isaac Hirsh as its first president. According to a brief article in the local newspaper six months later, “the association…has relieved the necessities of a good many poor that have applied to them for relief.” Thirty years later, the society, now named the Hebrew Relief Association but still led by Isaac Hirsh, remained active, though it only had 12 members and $36 in annual income. It did not function as a religious congregation, though Fredericksburg Jews did hold High Holiday services at the time. An estimated 60 Jews lived in Fredericksburg in 1907. By 1919, the Jewish community remained small, with 66 people, and the Hebrew Relief Association, now led by Isaac Hirsh’s son Maurice, was still the city’s only Jewish organization.

The Fredericksburg Jewish community consisted of only a handful of families, though they set down roots in the city. Several children of Fredericksburg’s first Jewish immigrants inherited family businesses or opened their own enterprises. David Hirsh’s son, whom he named Simon in honor of his brother, joined his father at the feed store after serving in the Navy. Simon managed the business for many years though it closed after he died in 1959. Joseph and Jacob Goldsmith helped their father Benjamin at B. Goldsmith & Son although Jacob opened the Opera House Saloon in 1898, one of Fredericksburg’s finest restaurants at the time. Joseph partnered with his father in 1902 and worked in the family business until he died in 1957; together, Benjamin and Joseph Goldsmith combined to manage the store for 96 years. Sydney Kaufman, son of Herman Kaufman, bought control of Loewenson’s Jewelry store in 1906 and managed it until he died in 1956

Civic Engagement

Though they were a tiny percentage of the population, Fredericksburg Jews became active civic leaders. Joseph Hable was elected to the City Council in 1894, while Simon Hirsh served as a council member from 1924 to 1944. Joseph Goldsmith served on the City Council for several terms in the early 1900s and later as President of the School Board. When there was a campaign in the city in 1926 to raise funds for a new hospital building, a “Hebrew Committee” was among the 13 community groups involved in the project. All of the members of the Hebrew Committee were second-generation Fredericksburg residents except for Maurice Gallant, who had moved to Fredericksburg from Baltimore around 1920 to manage the G & H Clothing Co. plant. Later in the 20th century, Jerry Miller led the local Chamber of Commerce and served on Mary Washington Hospital’s board of managers. In 1966, he was elected to the City Council. When Fredericksburg started a Wall of Honor in 2000 to commemorate noteworthy citizens who made outstanding contributions to the community, Miller was one of eight to be honored in the first year.

Though they were a tiny percentage of the population, Fredericksburg Jews became active civic leaders. Joseph Hable was elected to the City Council in 1894, while Simon Hirsh served as a council member from 1924 to 1944. Joseph Goldsmith served on the City Council for several terms in the early 1900s and later as President of the School Board. When there was a campaign in the city in 1926 to raise funds for a new hospital building, a “Hebrew Committee” was among the 13 community groups involved in the project. All of the members of the Hebrew Committee were second-generation Fredericksburg residents except for Maurice Gallant, who had moved to Fredericksburg from Baltimore around 1920 to manage the G & H Clothing Co. plant. Later in the 20th century, Jerry Miller led the local Chamber of Commerce and served on Mary Washington Hospital’s board of managers. In 1966, he was elected to the City Council. When Fredericksburg started a Wall of Honor in 2000 to commemorate noteworthy citizens who made outstanding contributions to the community, Miller was one of eight to be honored in the first year.

The Community Grows

An increasing number of Jewish families settled in Fredericksburg during the 1920s and 1930s. Many managed their own retail businesses, seeking to replicate the success of the Jews already established in Fredericksburg. The new families were mostly of Eastern European descent and had a history of Orthodox practice. They formed their own social group separate from the established Jewish families who were mostly of German descent. They acquired kosher food from Richmond and would travel to Baltimore and Richmond for the High Holidays. Reuben and Addie Miller moved to Fredericksburg in 1926 and opened a women’s specialty store. When it came time for their son Jerry to study for his bar mitzvah in 1936, they arranged for him to live with a family in Richmond for a full year where he received individual training; the ceremony was held in Baltimore at the Orthodox Beth Tfillah Congregation. Other Jewish families to move to Fredericksburg during this time were Karl and Ann Herr who owned the Mary and Washington Hotel, Harry and Anne Sager who opened a shoe store and dress shop, Frank and Sadie Levinson who operated the Washington Woolen Mills clothing store, and Abraham and Mae Suskins who ran the Globe Clothing Store. These families regularly gathered at the Sager or Gallant homes for religious services, especially for yahrzeit and mourning minyans.

An increasing number of Jewish families settled in Fredericksburg during the 1920s and 1930s. Many managed their own retail businesses, seeking to replicate the success of the Jews already established in Fredericksburg. The new families were mostly of Eastern European descent and had a history of Orthodox practice. They formed their own social group separate from the established Jewish families who were mostly of German descent. They acquired kosher food from Richmond and would travel to Baltimore and Richmond for the High Holidays. Reuben and Addie Miller moved to Fredericksburg in 1926 and opened a women’s specialty store. When it came time for their son Jerry to study for his bar mitzvah in 1936, they arranged for him to live with a family in Richmond for a full year where he received individual training; the ceremony was held in Baltimore at the Orthodox Beth Tfillah Congregation. Other Jewish families to move to Fredericksburg during this time were Karl and Ann Herr who owned the Mary and Washington Hotel, Harry and Anne Sager who opened a shoe store and dress shop, Frank and Sadie Levinson who operated the Washington Woolen Mills clothing store, and Abraham and Mae Suskins who ran the Globe Clothing Store. These families regularly gathered at the Sager or Gallant homes for religious services, especially for yahrzeit and mourning minyans.

Organized Jewish Life in Fredericksburg

Fredericksburg Jews began to discuss establishing a formal congregation in 1934 at the urging of Reverend R. V. Lancaster of the First Presbyterian Church, who was a friend of Harry Sager. Soon after, community members met with Rabbi Isadore Breslau of Washington D.C. in Reverend Lancaster’s study to discuss the potential congregation. The major issue was disagreement between the city’s German and Eastern European Jews over religious matters. After a negotiated agreement that the congregation would be Reform, the old-timers and newcomers banded together to form Beth Sholom Hebrew in May of 1936. The congregation held its first services a month later in the Masonic Hall. Ida Hirsh donated a Torah that she had brought from Prussia to the congregation. In the first three months, Rabbi Breslau commuted from Washington to Fredericksburg to conduct weekly Friday night services, but after he stopped coming, the congregation was without a rabbi until 1938. The congregation brought in Rabbi Hyman Perelmuter of Temple Emanuel in Yonkers to lead High Holiday services in 1936. Jewish business owners printed notices in the newspaper to inform the community that they would be closed on the holidays.

Despite its initial activity, Beth Sholom Hebrew struggled during its early years, especially in its effort to raise money for a synagogue. Fredericksburg’s Jewish community remained small, numbering only 70 people in 1937. At a board meeting in 1938, Simon Hirsh bluntly asked if the members wanted to continue the congregation. Abraham Suskins responded with conviction that the congregation must continue because it helped engender greater religious tolerance in Fredericksburg. Rededicated to their mission, the congregation hired its first rabbi, German immigrant Ulrich Steuer, a short time later.

Congregants increased their fundraising efforts, and in 1940 they broke ground on a temple building. With input from Rabbi Ulrich, the architectural design was intended to blend in to the town’s historic buildings and closely resembled a typical church. Maurice Gallant convinced G & H Manufacturing Co. to donate the land on Charlotte Street, several churches donated money for construction costs, and with other contributions from within and without the Jewish community, the congregation moved into their new building debt-free by the end of 1940. At the dedication ceremony, Rabbi Edward Calisch of Beth Ahabah in Richmond gave a sermon. Until the opening of the synagogue, Beth Sholom Hebrew services were held at the Parish House at St. George’s Episcopal Church.

The Orthodox and Reform members clashed in the congregation’s early years, but Rabbi Ulrich helped ease tensions. Reuben Miller was not in favor of the congregation’s Reform practices and would attend Orthodox High Holiday services outside of the city. Nevertheless, Miller was a dedicated contributor to the congregation as demonstrated by the stipulation in his will that two temple memberships be paid in his name.

Rabbi Ulrich served Fredericksburg until 1942 when he left to lead a congregation in Bloomington, Illinois. When the congregation was without a rabbi for a brief period, it brought in rabbis from Beth Ahabah in Richmond and Beth El Hebrew in Alexandria for special services. On several occasions during 1943, the Ladies Committee (later, the Sisterhood) asked the male congregants to lead services when there was no rabbi present, which they declined to do. Additionally, childrens’ programs disappeared after the rabbi left, so the Ladies Committee organized a religious school. The Ladies Committee performed many other vital duties for the congregation, including fundraising and keeping the temple’s financial records. Between 1943 and 1954, five different rabbis led the congregation, although none of them lasted more than three years. Rabbi Leon Eisberg, who was young and well-liked, came to Fredericksburg in 1950 but died suddenly in 1951; the congregation purchased and dedicated a torah in his name shortly thereafter. In 1955, the congregation bought land in Oak Hill Cemetery. Prior to this, most Fredericksburg Jews were buried in Baltimore or the District of Columbia.

Fredericksburg Jews began to discuss establishing a formal congregation in 1934 at the urging of Reverend R. V. Lancaster of the First Presbyterian Church, who was a friend of Harry Sager. Soon after, community members met with Rabbi Isadore Breslau of Washington D.C. in Reverend Lancaster’s study to discuss the potential congregation. The major issue was disagreement between the city’s German and Eastern European Jews over religious matters. After a negotiated agreement that the congregation would be Reform, the old-timers and newcomers banded together to form Beth Sholom Hebrew in May of 1936. The congregation held its first services a month later in the Masonic Hall. Ida Hirsh donated a Torah that she had brought from Prussia to the congregation. In the first three months, Rabbi Breslau commuted from Washington to Fredericksburg to conduct weekly Friday night services, but after he stopped coming, the congregation was without a rabbi until 1938. The congregation brought in Rabbi Hyman Perelmuter of Temple Emanuel in Yonkers to lead High Holiday services in 1936. Jewish business owners printed notices in the newspaper to inform the community that they would be closed on the holidays.

Despite its initial activity, Beth Sholom Hebrew struggled during its early years, especially in its effort to raise money for a synagogue. Fredericksburg’s Jewish community remained small, numbering only 70 people in 1937. At a board meeting in 1938, Simon Hirsh bluntly asked if the members wanted to continue the congregation. Abraham Suskins responded with conviction that the congregation must continue because it helped engender greater religious tolerance in Fredericksburg. Rededicated to their mission, the congregation hired its first rabbi, German immigrant Ulrich Steuer, a short time later.

Congregants increased their fundraising efforts, and in 1940 they broke ground on a temple building. With input from Rabbi Ulrich, the architectural design was intended to blend in to the town’s historic buildings and closely resembled a typical church. Maurice Gallant convinced G & H Manufacturing Co. to donate the land on Charlotte Street, several churches donated money for construction costs, and with other contributions from within and without the Jewish community, the congregation moved into their new building debt-free by the end of 1940. At the dedication ceremony, Rabbi Edward Calisch of Beth Ahabah in Richmond gave a sermon. Until the opening of the synagogue, Beth Sholom Hebrew services were held at the Parish House at St. George’s Episcopal Church.

The Orthodox and Reform members clashed in the congregation’s early years, but Rabbi Ulrich helped ease tensions. Reuben Miller was not in favor of the congregation’s Reform practices and would attend Orthodox High Holiday services outside of the city. Nevertheless, Miller was a dedicated contributor to the congregation as demonstrated by the stipulation in his will that two temple memberships be paid in his name.

Rabbi Ulrich served Fredericksburg until 1942 when he left to lead a congregation in Bloomington, Illinois. When the congregation was without a rabbi for a brief period, it brought in rabbis from Beth Ahabah in Richmond and Beth El Hebrew in Alexandria for special services. On several occasions during 1943, the Ladies Committee (later, the Sisterhood) asked the male congregants to lead services when there was no rabbi present, which they declined to do. Additionally, childrens’ programs disappeared after the rabbi left, so the Ladies Committee organized a religious school. The Ladies Committee performed many other vital duties for the congregation, including fundraising and keeping the temple’s financial records. Between 1943 and 1954, five different rabbis led the congregation, although none of them lasted more than three years. Rabbi Leon Eisberg, who was young and well-liked, came to Fredericksburg in 1950 but died suddenly in 1951; the congregation purchased and dedicated a torah in his name shortly thereafter. In 1955, the congregation bought land in Oak Hill Cemetery. Prior to this, most Fredericksburg Jews were buried in Baltimore or the District of Columbia.

After World War II

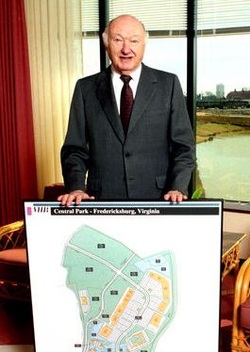

The Jewish community grew after World War II, reaching 140 people by 1960. Perhaps the most notable newcomer was Carl Silver, a World War II veteran who moved to Fredericksburg from Tappahannock, Virginia, around 1947. Silver started with a used car lot, and over the course of the 1950s acquired several other car dealerships. In the 1960s, Silver went into real estate, starting Silver Companies and buying up land alongside the newly constructed Interstate 95. His son Larry grew up helping to negotiate land deals and at age 19 was appointed president of Silver Companies, which built both residential and commercial developments. The company thrived as the Silvers became extremely wealthy and philanthropic. In 1982, Carl Silver donated 22 acres and $100,000 to build the Cancer Center of Virginia, which continues to treat patients today. He also donated 38 acres in one of his developments for a proposed National Slavery Museum. In 2006, he donated $2 million for the Carl D. Silver Health Center, which provides free health care and medications for the poor. While Carl Silver died in Fredericksburg in 2011, Larry Silver continues to operate the company.

In 1954, Beth Sholom hired Isadore Franzblau who, although not an ordained rabbi, led services as a chaplain at different army bases and then served as rabbi in Bristol, Tennessee, for eight years. With only 30 to 35 member families between 1950 and 1970, the congregation could not afford a full-time rabbi, so on weekdays, Franzblau and his wife Reba taught at Stafford County schools for many years. In 1957, Franzblau led Beth Sholom’s first bar mitzvah ceremony. The congregation also started confirmation classes in 1958. An active member of the Interfaith Council, Rabbi Franzblau often spoke at churches and formed warm relationships with Christian congregations. When Rabbi Franzblau retired in 1971, the congregation held a large farewell reception and hung portraits of the rabbi and his wife in the reception hall in recognition of their contributions to the temple. For the next 14 years, Beth Sholom brought in student rabbis from Hebrew Union College to lead services.

The Jewish community grew after World War II, reaching 140 people by 1960. Perhaps the most notable newcomer was Carl Silver, a World War II veteran who moved to Fredericksburg from Tappahannock, Virginia, around 1947. Silver started with a used car lot, and over the course of the 1950s acquired several other car dealerships. In the 1960s, Silver went into real estate, starting Silver Companies and buying up land alongside the newly constructed Interstate 95. His son Larry grew up helping to negotiate land deals and at age 19 was appointed president of Silver Companies, which built both residential and commercial developments. The company thrived as the Silvers became extremely wealthy and philanthropic. In 1982, Carl Silver donated 22 acres and $100,000 to build the Cancer Center of Virginia, which continues to treat patients today. He also donated 38 acres in one of his developments for a proposed National Slavery Museum. In 2006, he donated $2 million for the Carl D. Silver Health Center, which provides free health care and medications for the poor. While Carl Silver died in Fredericksburg in 2011, Larry Silver continues to operate the company.

In 1954, Beth Sholom hired Isadore Franzblau who, although not an ordained rabbi, led services as a chaplain at different army bases and then served as rabbi in Bristol, Tennessee, for eight years. With only 30 to 35 member families between 1950 and 1970, the congregation could not afford a full-time rabbi, so on weekdays, Franzblau and his wife Reba taught at Stafford County schools for many years. In 1957, Franzblau led Beth Sholom’s first bar mitzvah ceremony. The congregation also started confirmation classes in 1958. An active member of the Interfaith Council, Rabbi Franzblau often spoke at churches and formed warm relationships with Christian congregations. When Rabbi Franzblau retired in 1971, the congregation held a large farewell reception and hung portraits of the rabbi and his wife in the reception hall in recognition of their contributions to the temple. For the next 14 years, Beth Sholom brought in student rabbis from Hebrew Union College to lead services.

Beth Sholom's new synagogue

Beth Sholom's new synagogue

Changes in the Community

The Jewish community in Fredericksburg evolved during the 1960s and 1970s as an influx of Jewish professionals and government employees constituted an increasing percentage of the congregation. Many of the city’s Jewish-owned stores closed as new suburban malls and chain stores replaced family-owned businesses downtown while nearby military bases and Mary Washington Hospital drew new Jews to the area. Also, growing suburbanization made Fredericksburg into a bedroom community for people working in Washington, D.C. Between 1970 and 1990, the combined population of the city of Fredericksburg and the neighboring counties, Stafford and Spotsylvania, more than doubled from 55,461 to 137,666.

Beth Sholom started to grow as a result of this population increase. For years, the congregation had used the temple basement for its religious school classes. The space was already cramped as school enrollment fluctuated between 10 and 25 children for many years, but with this growth, the congregation built a new addition to their building in 1978. By 1982, Beth Sholom had 74 families and over 40 children in its religious school. Even with this addition, the temple could not accommodate the congregation’s growth. By the mid-1990s, with Beth Sholom numbering 116 families, they began to discuss building a new synagogue. Carl Silver donated 4.7 acres of land in southern Stafford County for the new building, and after a few years, the congregation financed a new temple on the site. The new building, which cost $1.8 million, was created with the hopes that the community would continue to grow.

Over the last 25 years, Beth Sholom has had periodic full-time rabbis. Rabbi Stephen Weisman, who served the congregation as a student rabbi, became the full-time rabbi after he was ordained in 1991, staying for six years. Linda Steigman was also hired as a full-time rabbi after serving the congregation as a rabbinic student. Devorah Lynn was Beth Sholom’s rabbi from 2006 to 2012. In 2013, the congregation had a student rabbi from Hebrew Union College.

The Jewish community in Fredericksburg evolved during the 1960s and 1970s as an influx of Jewish professionals and government employees constituted an increasing percentage of the congregation. Many of the city’s Jewish-owned stores closed as new suburban malls and chain stores replaced family-owned businesses downtown while nearby military bases and Mary Washington Hospital drew new Jews to the area. Also, growing suburbanization made Fredericksburg into a bedroom community for people working in Washington, D.C. Between 1970 and 1990, the combined population of the city of Fredericksburg and the neighboring counties, Stafford and Spotsylvania, more than doubled from 55,461 to 137,666.

Beth Sholom started to grow as a result of this population increase. For years, the congregation had used the temple basement for its religious school classes. The space was already cramped as school enrollment fluctuated between 10 and 25 children for many years, but with this growth, the congregation built a new addition to their building in 1978. By 1982, Beth Sholom had 74 families and over 40 children in its religious school. Even with this addition, the temple could not accommodate the congregation’s growth. By the mid-1990s, with Beth Sholom numbering 116 families, they began to discuss building a new synagogue. Carl Silver donated 4.7 acres of land in southern Stafford County for the new building, and after a few years, the congregation financed a new temple on the site. The new building, which cost $1.8 million, was created with the hopes that the community would continue to grow.

Over the last 25 years, Beth Sholom has had periodic full-time rabbis. Rabbi Stephen Weisman, who served the congregation as a student rabbi, became the full-time rabbi after he was ordained in 1991, staying for six years. Linda Steigman was also hired as a full-time rabbi after serving the congregation as a rabbinic student. Devorah Lynn was Beth Sholom’s rabbi from 2006 to 2012. In 2013, the congregation had a student rabbi from Hebrew Union College.

The Jewish Community in Fredericksburg Today

As of 2013, 110 families belong to Beth Sholom and approximately 70 children attend the religious school. With its large new building, the congregation has room to expand, though the community’s growth has slowed in recent years. Nevertheless, due to its proximity to Washington and the growth of Northern Virginia, the future of the Fredericksburg Jewish community looks bright.