Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Harrisonburg, Virginia

Historical Overview

|

In 1789, Thomas Harrison donated land for the creation of a town that was named in his honor. The surrounding Shenandoah Valley was initially settled by German and Scots-Irish immigrants who established farms and mills. Over the years, Harrisonburg has evolved from a sleepy rural enclave to a bustling college town anchored by James Madison University, with a steadily growing Jewish community.

|

Stories of the Jewish Community in Harrisonburg

Baruch Ney

Baruch Ney

Early Settlers

The four founding families of Harrisonburg’s Jewish community arrived in the Shenandoah Valley in 1859. Herman Heller and Leopold Wise, natives of Chodau, Bohemia, arrived in Harrisonburg and became merchants. Samuel Loewner, a native of Konigsworth, Bohemia, first lived in nearby Dayton and in neighboring Augusta County before moving to Harrisonburg. Joseph Heller, also a Konigswarth native, lived in Mt. Crawford before settling in Harrisonburg.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Albert and Adolph Wise, Emanuel Loewner, and Jonas Heller enlisted in the Confederate Army and served under General Stonewall Jackson. While Harrisonburg’s small Jewish community threw its support behind the Confederacy, the town was split over Virginia’s decision to leave the Union. The city’s representatives in Richmond did not support secession.

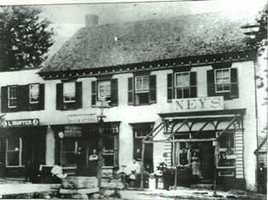

After the Civil War more Jewish families arrived from Bohemia and other German territories. Samuel Klingenstein, Moritz Heller, Samuel Gradwohl, Sigmund Strauss, Simon Oestreicher, Ludwig Hirsch, William Loeb, and Baruch and Joseph Ney all settled in Harrisonburg during this period. I.N. Pinkus, and Bernard Bloom arrived shortly after the immediate post-Civil War surge of Jewish settlement. Baruch Ney arrived in the United States from Neiderstetten, Württemberg, in 1865. He peddled in New York state, sold photographs of Abraham Lincoln in front of Trinity Church in New York City, and briefly worked in Baltimore, before Leopold Wise helped him settle in Harrisonburg. After operating a confectionery shop with Wise, Ney opened a men’s clothing store in 1874. Dubbed “one of Harrisonburg’s outstanding business geniuses” by a local historian, Ney opened the town’s first five and ten cent store and eventually turned B. Ney & Sons into a department store. When he died in 1915, the former peddler had become a distinguished merchant.

The four founding families of Harrisonburg’s Jewish community arrived in the Shenandoah Valley in 1859. Herman Heller and Leopold Wise, natives of Chodau, Bohemia, arrived in Harrisonburg and became merchants. Samuel Loewner, a native of Konigsworth, Bohemia, first lived in nearby Dayton and in neighboring Augusta County before moving to Harrisonburg. Joseph Heller, also a Konigswarth native, lived in Mt. Crawford before settling in Harrisonburg.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Albert and Adolph Wise, Emanuel Loewner, and Jonas Heller enlisted in the Confederate Army and served under General Stonewall Jackson. While Harrisonburg’s small Jewish community threw its support behind the Confederacy, the town was split over Virginia’s decision to leave the Union. The city’s representatives in Richmond did not support secession.

After the Civil War more Jewish families arrived from Bohemia and other German territories. Samuel Klingenstein, Moritz Heller, Samuel Gradwohl, Sigmund Strauss, Simon Oestreicher, Ludwig Hirsch, William Loeb, and Baruch and Joseph Ney all settled in Harrisonburg during this period. I.N. Pinkus, and Bernard Bloom arrived shortly after the immediate post-Civil War surge of Jewish settlement. Baruch Ney arrived in the United States from Neiderstetten, Württemberg, in 1865. He peddled in New York state, sold photographs of Abraham Lincoln in front of Trinity Church in New York City, and briefly worked in Baltimore, before Leopold Wise helped him settle in Harrisonburg. After operating a confectionery shop with Wise, Ney opened a men’s clothing store in 1874. Dubbed “one of Harrisonburg’s outstanding business geniuses” by a local historian, Ney opened the town’s first five and ten cent store and eventually turned B. Ney & Sons into a department store. When he died in 1915, the former peddler had become a distinguished merchant.

Adolph Wise

Adolph Wise

Organized Jewish Life in Harrisonburg

Immigrants like Ney maintained a strong German identity, and were active in German fraternal organizations in Harrisonburg. William Loeb was elected the first president of the Harrisonburg Turnverin, the town’s athletic clubs for people of German ancestry, in 1867. Maurice Heller became president after Loeb in 1869. While some of these early settlers worked to preserve their German identity, they also sought to preserve their Jewish traditions. In 1867 the Jewish community began renting a room for prayers in the Paul Building on West Market Street. Simon Oestreicher, Samuel Loewner, and Adolph Wise led services in a traditional, Orthodox style. The group continued growing and moved twice in 1870 before settling on a rented location at the First National Bank Building. In 1870, the group acquired a Torah and established a Ladies’ Auxiliary. Three years later, Harrisonburg Jews founded a B’nai B’rith Chapter, with Adolph Wise elected the first president. In 1877, the congregation formally incorporated as the Hebrew Friendship Congregation. A year earlier, the group had purchased land for a cemetery following the death of Baruch Ney’s daughter Emma. With a growing community of ten families and 40 children, the congregation hired a rabbi in 1877, but he only stayed for one year. The congregation hired Rabbi M. Strauss in 1883 to lead weekly services and run a Hebrew school, but he too had a short tenure.

Harrisonburg’s Jewish population grew to 93 people by 1890. That same year the congregation formed a building committee headed by Baruch Ney to raise funds for a synagogue. With funds from the building committee, proceeds from a bazaar organized by the Women’s Auxiliary, and donations from congregations in the North, the congregation bought a property two blocks from Court Square for $475. The cornerstone was laid on July 4, 1891 and the building was completed in time for Rosh Hashanah that year.

Immigrants like Ney maintained a strong German identity, and were active in German fraternal organizations in Harrisonburg. William Loeb was elected the first president of the Harrisonburg Turnverin, the town’s athletic clubs for people of German ancestry, in 1867. Maurice Heller became president after Loeb in 1869. While some of these early settlers worked to preserve their German identity, they also sought to preserve their Jewish traditions. In 1867 the Jewish community began renting a room for prayers in the Paul Building on West Market Street. Simon Oestreicher, Samuel Loewner, and Adolph Wise led services in a traditional, Orthodox style. The group continued growing and moved twice in 1870 before settling on a rented location at the First National Bank Building. In 1870, the group acquired a Torah and established a Ladies’ Auxiliary. Three years later, Harrisonburg Jews founded a B’nai B’rith Chapter, with Adolph Wise elected the first president. In 1877, the congregation formally incorporated as the Hebrew Friendship Congregation. A year earlier, the group had purchased land for a cemetery following the death of Baruch Ney’s daughter Emma. With a growing community of ten families and 40 children, the congregation hired a rabbi in 1877, but he only stayed for one year. The congregation hired Rabbi M. Strauss in 1883 to lead weekly services and run a Hebrew school, but he too had a short tenure.

Harrisonburg’s Jewish population grew to 93 people by 1890. That same year the congregation formed a building committee headed by Baruch Ney to raise funds for a synagogue. With funds from the building committee, proceeds from a bazaar organized by the Women’s Auxiliary, and donations from congregations in the North, the congregation bought a property two blocks from Court Square for $475. The cornerstone was laid on July 4, 1891 and the building was completed in time for Rosh Hashanah that year.

B. Ney Clothing Store

B. Ney Clothing Store

Life in the Greater Community

In 1878, conflict erupted between the Jewish community and Rockingham Register newspaper. On January 24, 1878, the paper printed an article titled “The Starch Taken Out of a Jew” about a group of men that bullied a traveling Jewish peddler. In response, Harrisonburg Jews held a meeting in which they decided to submit a letter criticizing the newspaper for identifying the victim as Jewish and using “the word ‘Jew’ in a manner which betrays prejudice, insult, and contempt.” The group, led by William Loeb, H.E. Woolf, and Augustine Heller also declared that Jewish merchants would no longer advertise in the Register. When Rabbi Sterne published another letter about the incident in a different local newspaper, the Register responded with a long editorial that was meant to “take a little starch out of this ‘doctor’ [rabbi] just like the boys took the starch out of the young Jew.” The editor called Jews “a foreign element fostered on American soil” and asked rhetorically whether they sought “to monopolize trade and push to the wall every tradesman who is not a Hebrew.”

These newspaper attacks seem to be anomalous as Jews went on to become important civic and business leaders in Harrisonburg. Active in civic affairs since his days as president of the Turnverein, William Loeb was a member of city council in 1890. Adolph Wise, Leopold Wise’s son, served on city council in 1890. His daughter Teresa would marry Abe Loewner, who served several terms on city council. Loewner was head of the finance committee when the town installed modern sewage, water, lights and power systems. He also operated his own store. Morris Spiro came to Harrisonburg in 1906 and served many years as president of the Harrisonburg and Rockingham County Red Cross.

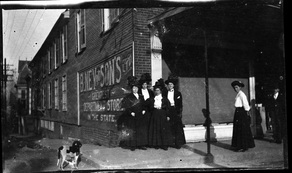

Following Baruch Ney’s death in 1914, his son Isaac became president of the company until his death in 1941. Involved in everything from infrastructure improvement to the Kiwanis Club, Isaac Ney helped organize the Harrisonburg Loan & Thrift Corporation. Henry Ney, the second of the Ney children, was secretary of the Hebrew Friendship Congregation, a charter member of the Elks Club, and served on the board of the Rockingham Memorial Hospital. He was a key figure in the establishment of Shenandoah Valley, Inc. in the 1920s, a nonprofit that promoted tourism in the area. After Isaac Ney’s death in 1941, Henry became president of B. Ney & Sons.

In 1878, conflict erupted between the Jewish community and Rockingham Register newspaper. On January 24, 1878, the paper printed an article titled “The Starch Taken Out of a Jew” about a group of men that bullied a traveling Jewish peddler. In response, Harrisonburg Jews held a meeting in which they decided to submit a letter criticizing the newspaper for identifying the victim as Jewish and using “the word ‘Jew’ in a manner which betrays prejudice, insult, and contempt.” The group, led by William Loeb, H.E. Woolf, and Augustine Heller also declared that Jewish merchants would no longer advertise in the Register. When Rabbi Sterne published another letter about the incident in a different local newspaper, the Register responded with a long editorial that was meant to “take a little starch out of this ‘doctor’ [rabbi] just like the boys took the starch out of the young Jew.” The editor called Jews “a foreign element fostered on American soil” and asked rhetorically whether they sought “to monopolize trade and push to the wall every tradesman who is not a Hebrew.”

These newspaper attacks seem to be anomalous as Jews went on to become important civic and business leaders in Harrisonburg. Active in civic affairs since his days as president of the Turnverein, William Loeb was a member of city council in 1890. Adolph Wise, Leopold Wise’s son, served on city council in 1890. His daughter Teresa would marry Abe Loewner, who served several terms on city council. Loewner was head of the finance committee when the town installed modern sewage, water, lights and power systems. He also operated his own store. Morris Spiro came to Harrisonburg in 1906 and served many years as president of the Harrisonburg and Rockingham County Red Cross.

Following Baruch Ney’s death in 1914, his son Isaac became president of the company until his death in 1941. Involved in everything from infrastructure improvement to the Kiwanis Club, Isaac Ney helped organize the Harrisonburg Loan & Thrift Corporation. Henry Ney, the second of the Ney children, was secretary of the Hebrew Friendship Congregation, a charter member of the Elks Club, and served on the board of the Rockingham Memorial Hospital. He was a key figure in the establishment of Shenandoah Valley, Inc. in the 1920s, a nonprofit that promoted tourism in the area. After Isaac Ney’s death in 1941, Henry became president of B. Ney & Sons.

B. Ney Department Store

B. Ney Department Store

The Post-War Years

Several Jewish-owned stores lined downtown Harrisonburg during the post-war years. Miller’s, Harry’s Appliance, and Blatt’s, a dry cleaning company, all flourished during the 1950s. The Ney family owned several different stores. When Eddie Ney died in 1940, the business he ran, Joseph Ney & Sons, split into two, with Eddie’s son Irving and son-in-law Adrian Sonn maintaining the name, while Eddie’s brother Alfred opened his own new store. The now separate companies operated their business out of the same store for several years. In 1950, Irving Ney and Sonn purchased a new building for Joseph Ney & Sons. In the 1960s, they opened a separate men’s clothing annex across the street. A few years later, they sold the store, which finally went out of business in the late 1970s.

The B. Ney store shut down at some point in the 1950s. Eddie Ney’s grandson, also named Eddie Ney, opened Ney’s House of Fashion in 1967 and remained open until about 1981. Alfred Ney’s store remained downtown until 1995 when it closed its downtown and mall locations and relocated to a strip mall. It closed completely in 2000. Bill Ney, a cousin who had managed Alfred Ney’s, opened his own men’s clothing store in 2000 before closing it in 2008.

Harrisonburg’s Jewish population increased slightly during the post-war years, growing from 104 people in 1937 to 160 by 1968. A handful of new Jewish families began arriving around the 1950s. Ruth and Harry Clayman came in 1950 and became active in the congregation. Harry, an optometrist, served terms as synagogue secretary and president of the Men’s Club. He was also a founding member of the Valley Players and the Grand Chaplain of the Grand Masonic Lodge of Virginia. Ruth was a founder and president of the Rockingham Memorial Hospital Auxiliary Organization, and taught in the religious school. Joshua Robinson, a native of nearby Luray, returned to his hometown in 1949 to open a law practice. Beginning in 1972 Robinson enjoyed a long tenure as a circuit court judge. His wife, Estelle Good Robinson, was a Brooklyn native who first came to Virginia in the 1940s to attend Madison College. She taught religious school at Beth El Congregation as an undergraduate student and continued to serve the local Jewish community after settling permanently in Luray.

Joseph Mintzer came to Harrisonburg from New York to open a pants manufacturing plant in 1937. Mintzer immersed himself in Harrisonburg’s commercial, religious, and civic life. He served three terms on city council, was vice-mayor for three years, and was a founding member of the local United Fund charity. Mintzer was also president of Temple Beth El and the local B’nai B’rith chapter. When Mintzer died in 1967, Harrisonburg mayor Frank Switzer said in a newspaper article “I know of no other person who has done as much for many people.” Mintzer’s wife Minna established the local Hadassah chapter and served as president of the Sisterhood.

Several Jewish-owned stores lined downtown Harrisonburg during the post-war years. Miller’s, Harry’s Appliance, and Blatt’s, a dry cleaning company, all flourished during the 1950s. The Ney family owned several different stores. When Eddie Ney died in 1940, the business he ran, Joseph Ney & Sons, split into two, with Eddie’s son Irving and son-in-law Adrian Sonn maintaining the name, while Eddie’s brother Alfred opened his own new store. The now separate companies operated their business out of the same store for several years. In 1950, Irving Ney and Sonn purchased a new building for Joseph Ney & Sons. In the 1960s, they opened a separate men’s clothing annex across the street. A few years later, they sold the store, which finally went out of business in the late 1970s.

The B. Ney store shut down at some point in the 1950s. Eddie Ney’s grandson, also named Eddie Ney, opened Ney’s House of Fashion in 1967 and remained open until about 1981. Alfred Ney’s store remained downtown until 1995 when it closed its downtown and mall locations and relocated to a strip mall. It closed completely in 2000. Bill Ney, a cousin who had managed Alfred Ney’s, opened his own men’s clothing store in 2000 before closing it in 2008.

Harrisonburg’s Jewish population increased slightly during the post-war years, growing from 104 people in 1937 to 160 by 1968. A handful of new Jewish families began arriving around the 1950s. Ruth and Harry Clayman came in 1950 and became active in the congregation. Harry, an optometrist, served terms as synagogue secretary and president of the Men’s Club. He was also a founding member of the Valley Players and the Grand Chaplain of the Grand Masonic Lodge of Virginia. Ruth was a founder and president of the Rockingham Memorial Hospital Auxiliary Organization, and taught in the religious school. Joshua Robinson, a native of nearby Luray, returned to his hometown in 1949 to open a law practice. Beginning in 1972 Robinson enjoyed a long tenure as a circuit court judge. His wife, Estelle Good Robinson, was a Brooklyn native who first came to Virginia in the 1940s to attend Madison College. She taught religious school at Beth El Congregation as an undergraduate student and continued to serve the local Jewish community after settling permanently in Luray.

Joseph Mintzer came to Harrisonburg from New York to open a pants manufacturing plant in 1937. Mintzer immersed himself in Harrisonburg’s commercial, religious, and civic life. He served three terms on city council, was vice-mayor for three years, and was a founding member of the local United Fund charity. Mintzer was also president of Temple Beth El and the local B’nai B’rith chapter. When Mintzer died in 1967, Harrisonburg mayor Frank Switzer said in a newspaper article “I know of no other person who has done as much for many people.” Mintzer’s wife Minna established the local Hadassah chapter and served as president of the Sisterhood.

Hebrew Friendship Congregation's first synagogue

Hebrew Friendship Congregation's first synagogue

Congregation at the Mid-Century

The Hebrew Friendship Congregation reached a plateau of around 50 members in the years after World War II. Rabbi Joseph Freedman served the congregation from 1947 to 1952, and was succeeded Israel Kaplan, who led the congregation for the next three years. For the remainder of the 1950s and 60s, Hebrew Friendship had a few other short-term rabbis, while relying on student rabbis and lay leaders for most of these years. The congregation established a Brotherhood in 1950, which supported the religious school and focused on interfaith programming with Christian churches in town. The urban renewal movement of the 1950s and 1960s that demolished scores of neighborhoods across the country spelled the demise of the Hebrew Friendship Congregation’s downtown building. The congregation expected urban renewal would claim the building and had been discussing purchasing or constructing a new building for several years. In 1964, the congregation which had officially changed its name to Temple Beth El the previous year, opened its new building on Old Furnace Road, which still serves the congregation today. One of its most striking features is a 13 x 8 foot replica of the Beit Alpha Mosaic, made by congregants themselves. The original Beit Alpha Mosaic is located outside of Beit Shean, Israel, and was created during the Byzantine period.

The Hebrew Friendship Congregation reached a plateau of around 50 members in the years after World War II. Rabbi Joseph Freedman served the congregation from 1947 to 1952, and was succeeded Israel Kaplan, who led the congregation for the next three years. For the remainder of the 1950s and 60s, Hebrew Friendship had a few other short-term rabbis, while relying on student rabbis and lay leaders for most of these years. The congregation established a Brotherhood in 1950, which supported the religious school and focused on interfaith programming with Christian churches in town. The urban renewal movement of the 1950s and 1960s that demolished scores of neighborhoods across the country spelled the demise of the Hebrew Friendship Congregation’s downtown building. The congregation expected urban renewal would claim the building and had been discussing purchasing or constructing a new building for several years. In 1964, the congregation which had officially changed its name to Temple Beth El the previous year, opened its new building on Old Furnace Road, which still serves the congregation today. One of its most striking features is a 13 x 8 foot replica of the Beit Alpha Mosaic, made by congregants themselves. The original Beit Alpha Mosaic is located outside of Beit Shean, Israel, and was created during the Byzantine period.

Temple Beth El's new synagogue

Temple Beth El's new synagogue

James Madison University

The Harrisonburg Jewish community has been bolstered by the growth of James Madison University, which saw its number of students and faculty triple between the 1970s and 1990s. Like many universities in Virginia, Madison College, now James Madison University, did not start hiring Jewish faculty members until the 1950s. John Stewart became first Jewish faculty member at Madison College when he was hired as an associate professor in the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures in 1958. A scholar of Pennsylvania-German Folklore, Stewart was superintendent of the Beth El Hebrew school and a two-time synagogue board member. James Madison University hired Andrew Kohen as an economics professor in 1976. Kohen taught at JMU for over 35 years and served on the Anti-Defamation League advisory board of Virginia and North Carolina and the Virginia State Board of the National Conference of Christians and Jews. He was also president of the congregation for several years. Ralph Cohen, a faculty member at JMU in the 1980s, co-founded the Shakespeare Express, a traveling performance troupe in 1988. Originally comprised of JMU theater students, the Shakespeare Express has evolved into the American Shakespeare Center in neighboring Staunton, where Cohen is still the director.

JMU’s Jewish faculty members were crucial in efforts to banish religion from Harrisonburg’s public schools. Journalism professor Alan Neckowitz was a plaintiff in a court case in 1975 that ended the Weekday Religious Education Program in Harrisonburg city schools. During Weekday Religious Education, students left school grounds for about an hour and attended religious classes in buses parked next to school property. Kohen and special education professor Jerry Minskoff worked with the Harrisonburg schools to end the practice of distributing Gideon’s Bibles at high school graduations later in the decade.

The Harrisonburg Jewish community has been bolstered by the growth of James Madison University, which saw its number of students and faculty triple between the 1970s and 1990s. Like many universities in Virginia, Madison College, now James Madison University, did not start hiring Jewish faculty members until the 1950s. John Stewart became first Jewish faculty member at Madison College when he was hired as an associate professor in the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures in 1958. A scholar of Pennsylvania-German Folklore, Stewart was superintendent of the Beth El Hebrew school and a two-time synagogue board member. James Madison University hired Andrew Kohen as an economics professor in 1976. Kohen taught at JMU for over 35 years and served on the Anti-Defamation League advisory board of Virginia and North Carolina and the Virginia State Board of the National Conference of Christians and Jews. He was also president of the congregation for several years. Ralph Cohen, a faculty member at JMU in the 1980s, co-founded the Shakespeare Express, a traveling performance troupe in 1988. Originally comprised of JMU theater students, the Shakespeare Express has evolved into the American Shakespeare Center in neighboring Staunton, where Cohen is still the director.

JMU’s Jewish faculty members were crucial in efforts to banish religion from Harrisonburg’s public schools. Journalism professor Alan Neckowitz was a plaintiff in a court case in 1975 that ended the Weekday Religious Education Program in Harrisonburg city schools. During Weekday Religious Education, students left school grounds for about an hour and attended religious classes in buses parked next to school property. Kohen and special education professor Jerry Minskoff worked with the Harrisonburg schools to end the practice of distributing Gideon’s Bibles at high school graduations later in the decade.

The Jewish Community in Harrisonburg Today

Temple Beth El mosaic

Temple Beth El mosaic

In the early 1970s Congregation Beth- El revived the joint rabbi program with House of Israel in Staunton. Rabbi E. Robert Kraus was hired by Beth El and a subcontract was written that he would spend one third of his time in Staunton. The joint rabbi partnership became permanent with the hiring of Rabbi Douglas Weber in 1983. Rabbis Lynne Landsberg, Dan Fink, Laura Rappaport, Jonathan Biatch and Jacqueline Romm Satlow have followed Weber. Rabbi Ariel J. Friedlander led Beth-El and House of Israel from 1997 to 2003. Rabbi Joe Blair, began to serve both congregations in 2003.

Today, much of the Harrisonburg Jewish community is affiliated with James Madison University. There are also several doctors, lawyers and a growing number of retirees. Temple Beth-El is in good health with 73 families about 30 students enrolled in its religious school. A Chabad House opened on campus in early 2013. Thanks to the strength of the university, the Jewish community of Harrisonburg is poised to continue its slow but steady growth.

Today, much of the Harrisonburg Jewish community is affiliated with James Madison University. There are also several doctors, lawyers and a growing number of retirees. Temple Beth-El is in good health with 73 families about 30 students enrolled in its religious school. A Chabad House opened on campus in early 2013. Thanks to the strength of the university, the Jewish community of Harrisonburg is poised to continue its slow but steady growth.