Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Hopewell, Virginia

Hopewell: Historical Overview

|

For most of its existence, Hopewell, Virginia, was a very small, quiet town located on the James and Appomattox Rivers. Founded by Sir Thomas Dale in 1613 as “City Point,” Hopewell was home to just 300 residents until 1914, when it witnessed a major boom. That year, the DuPont Company, a large dynamite manufacturer, decided to build a plant in Hopewell, bringing over 40,000 employees to the city within a few months and thus giving Hopewell the name “Wonder City.” In 1916, Hopewell was officially incorporated, as an independent city, and soon joined Petersburg and Colonial Heights to form Virginia’s “Tri-City” area. Jews came to Hopewell soon after DuPont, and a small number of Jews remain in the Hopewell area today

|

RESOURCES

Images courtesy of Appomattox Regional Library |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Hopewell

Garfinkel Brothers store

Garfinkel Brothers store

Early Residents

Jewish merchants first settled in Hopewell within a year of DuPont’s arrival. The Garfinkel brothers were among the earliest to arrive, after immigrating to the U.S. from Lithuania in the early 1890s. Recognizing the business opportunity brought about by the DuPont plant, the brothers—Samuel, Harry, and Louis—all moved to Hopewell by 1915. Together, they established a dry goods store named Garfinkel’s on Broadway Avenue, which later evolved into a women’s fashion store.

B.B. Haberer was another early Jewish merchant in Hopewell. In 1915, he and his wife Sarah left Washington, D.C. to set up Newport Stores in Hopewell, just as the city began to boom. Shortly after his arrival, Haberer became one of the most prominent men in the community, serving as a member of the local school board, the Hopewell Board of Trade, and the Odd Fellows fraternal organization. Haberer also played an active role in the budding Jewish community, which mostly comprised of new merchants.

In 1916, just a year after he settled in Hopewell, Haberer helped establish the Hopewell Hebrew Congregation. The address of the congregation was listed in the City Directory as 107-A West Poythress Ave, the same street as Haberer’s own store downtown. By 1919, the congregation, which only met for services on the High Holidays, had 45 families and 10 students in its religious school. Their lay-led services were in Hebrew.

Jewish merchants first settled in Hopewell within a year of DuPont’s arrival. The Garfinkel brothers were among the earliest to arrive, after immigrating to the U.S. from Lithuania in the early 1890s. Recognizing the business opportunity brought about by the DuPont plant, the brothers—Samuel, Harry, and Louis—all moved to Hopewell by 1915. Together, they established a dry goods store named Garfinkel’s on Broadway Avenue, which later evolved into a women’s fashion store.

B.B. Haberer was another early Jewish merchant in Hopewell. In 1915, he and his wife Sarah left Washington, D.C. to set up Newport Stores in Hopewell, just as the city began to boom. Shortly after his arrival, Haberer became one of the most prominent men in the community, serving as a member of the local school board, the Hopewell Board of Trade, and the Odd Fellows fraternal organization. Haberer also played an active role in the budding Jewish community, which mostly comprised of new merchants.

In 1916, just a year after he settled in Hopewell, Haberer helped establish the Hopewell Hebrew Congregation. The address of the congregation was listed in the City Directory as 107-A West Poythress Ave, the same street as Haberer’s own store downtown. By 1919, the congregation, which only met for services on the High Holidays, had 45 families and 10 students in its religious school. Their lay-led services were in Hebrew.

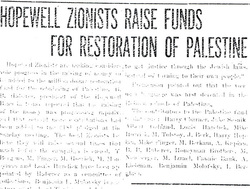

Article in local newspaper, Feb. 10, 1918

Article in local newspaper, Feb. 10, 1918

Haberer also brought Zionist activity to the city. He was the founder and served as president of Hopewell’s local chapter of the Virginia Zionists Association, which sponsored events like Purim festivals and lectures by national speakers. Unfortunately, in 1918, just as the organization was getting under way, Haberer died suddenly of meningitis, leaving Michael Finger as president. In speaking of Haberer’s contributions to the city, Hopewell’s Mayor A.D. Harrison publically stated: “I regarded him as one of my dependable allies in…the moral advancement of the community.” There was no Jewish burial ground in Hopewell, so Haberer was buried in Petersburg’s Brith Achim cemetery.

Yet another prominent early Jewish resident in Hopewell was John P. Goodman, who also arrived in town shortly after the DuPont plant. Unlike most Jews in the city, however, Goodman was a lawyer, not a merchant. In 1918, he was elected to the position of Commonwealth Attorney in Hopewell, becoming the first Jew in Virginia to ever hold this office. His position occasionally put Goodman at odds with emerging local business owners, many of whom were also Jewish. In February 1918, he ordered local merchants to close their stands on Sundays, as they were “congesting traffic in the streets.” This upset many merchants, who said the ruling hurt their business, and sparked “more discussion than any local issue has started in many months,” according to the Hopewell Record.

Yet another prominent early Jewish resident in Hopewell was John P. Goodman, who also arrived in town shortly after the DuPont plant. Unlike most Jews in the city, however, Goodman was a lawyer, not a merchant. In 1918, he was elected to the position of Commonwealth Attorney in Hopewell, becoming the first Jew in Virginia to ever hold this office. His position occasionally put Goodman at odds with emerging local business owners, many of whom were also Jewish. In February 1918, he ordered local merchants to close their stands on Sundays, as they were “congesting traffic in the streets.” This upset many merchants, who said the ruling hurt their business, and sparked “more discussion than any local issue has started in many months,” according to the Hopewell Record.

John P. Goodman

John P. Goodman

For the most part, though, Goodman was regarded as a strong leader throughout Hopewell, and especially in the growing Jewish community. Goodman was president of the Hopewell Jewish Congregation in 1919. He was also president of the newly established Young Men’s Hebrew Association, and led a large-scale fundraising campaign to establish a YMHA building in Hopewell. The building was designed to provide a home for Jewish soldiers at the recently established Camp Lee nearby, which hosted over 60,000 soldiers training to fight in World War I. In building a YMHA, the Hopewell community hoped to create a comfortable space for Jewish boys far from home with entertainment, social company, and holiday gatherings. Along with John Goodman, Louis Seigel, R. Honeyman, and Albert Whesky led the fundraising effort. These men, according to an article in the Hopewell Record, were “some of the most prominent business and professional men in the city.” It was thus predicted that they would have no problem raising the necessary funds.

Indeed, the prediction proved correct. Within just a few months, Goodman announced that the YMHA had raised enough money to break ground for their new building. They received funding not only from local Jewish sources, but also from Jews across the country interested in helping the Jewish soldiers. In addition, two of Hopewell’s most respected non-Jewish citizens—Mayor A.D. Harrison and Richard Eppes, a wealthy landowner—contributed to the campaign as well.

Indeed, the prediction proved correct. Within just a few months, Goodman announced that the YMHA had raised enough money to break ground for their new building. They received funding not only from local Jewish sources, but also from Jews across the country interested in helping the Jewish soldiers. In addition, two of Hopewell’s most respected non-Jewish citizens—Mayor A.D. Harrison and Richard Eppes, a wealthy landowner—contributed to the campaign as well.

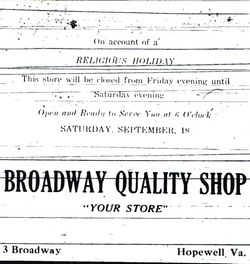

1926 ad announcing the closing of

1926 ad announcing the closing of A.A. Spiegel's clothing store for Rosh Hashanah

The Community Declines, Rebounds, Declines

In November 1918, six months after the community was scheduled to start building, World War I came to an end and soldiers began to evacuate Camp Lee. Although the base remained open as an out-processing center for two years, officially closing in 1921, the city of Hopewell essentially shut down immediately after the war when DuPont closed its guncotton manufacturing plant. As a result, merchants and former employees left the city in droves, and Hopewell became a ghost town—but only briefly. In 1923, another large manufacturer, Tubize Corporation (later acquired by Firestone Tire and Rubber Company), established an artificial silk plant on DuPont’s old site in Hopewell, once again bringing employment and economic activity to the town.

Within a few years of Tubize’s arrival, a new wave of Jewish merchants began to settle in Hopewell to cater to the plant’s employees. Once again, many quickly gained prominence in business and civic affairs. A.A. Spiegel, for instance, owned Broadway Quality Shop, and also served as Vice President of the Retail Merchant Association. Down the street on Broadway Avenue, Austrian immigrant Saul Bisger owned and operated Saul’s Style Shop. Bisger was also an active member of the DuPont Lodge, Kiwanis Club, and the Knights of Pythias. Meanwhile, the Garfinkel brothers—among the only merchants to survive the economic downturn after DuPont’s close—continued to expand their business as women’s clothing retailers in the mid-1920s. Samuel Garfinkel, additionally, opened a grocery store downtown.

By 1929, although the Hopewell Hebrew Congregation remained listed in the City Directory—along with about 10 Jewish-owned businesses—religious activity appears to have greatly slowed. There is no evidence that the congregation ever hired a rabbi, nor did they purchase land for a cemetery. Hopewell’s Jewish residents were usually buried in Petersburg, Richmond, or Washington, D.C.

In 1934, the Tubize-Chatillon company closed their plant in Hopewell in response to declining profits and workers’ attempts to unionize. The closure left about 2,600 employees jobless. Although other manufacturing plants had since arrived in the city—most notably, Allied Chemical and Hercules Chemical—Hopewell’s growth slowed after its short boom in the mid-1920s. By 1937, only about 50 Jews lived in Hopewell, and there was no longer any active religious congregation. Instead, Jewish residents began to join congregations in Petersburg and Washington, D.C. The merchant Saul Bisger, for instance, was an active member of Brith Achim, the Conservative congregation in Petersburg, just 10 miles away, until he died in 1946. Meanwhile, Harry Abrams, a well-known Hopewell merchant, joined D.C.’s Washington Hebrew Congregation.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Jewish population of Hopewell dwindled to only about eight Jewish families, including the Goldbergs, Gordons, Goodmans, Garfinkels, Sellingers, Marks, Sears, and Abrams. Many of these residents had grown up in Hopewell and continued their families’ legacy as active civic and business leaders. In 1962, Sol Goodman, son of John P. Goodman, assumed his father’s position as Commonwealth Attorney. He also served on the City Council for eleven years. Seymour Garfinkel took over his father’s business as co-owner of Garfinkel’s Ladies’Apparel on Broadway Street, which later moved to Cavalier Square. Before closing in 1997, Garfinkel’s was recognized as the Tri-City area’s third-oldest store and one of the earliest to offer charge accounts to customers. Moreover, Seymour Garfinkel is said to have been the first white retailer in Hopewell to hire an African American employee in the 1960s. During his 35 years managing the store, Seymour also served as president of the Retail Merchants Association and the Chamber of Commerce.

By the early 1970s, Hopewell witnessed another population decline, largely due to continuing plant closures and middle class movement to the Prince George and Chesterfield suburbs. The city’s Jewish population, too, continued to decrease, as no new families moved to the area. Nevertheless, one Jewish group in Hopewell was able to remain alive during these decades: the Jewish Women’s Club. Helene Goodman, wife of the prominent attorney John P. Goodman, served as one of the group’s founding members and later as president. Frances Garfinkel, wife of Seymour and co-owner of Garfinkel’s Ladies Apparel, also served as the club’s president. The group, though very small, continued to meet until the late 1970s.

Meanwhile, the few remaining Jewish families in Hopewell joined Petersburg’s Conservative Congregation Brith Achim. Some grew very involved. In 1975, Sol Goodman served as president of the congregation. Seymour Garfinkel also served as a board member and vice president of Brith Achim, as well as chairman of the Tri-City Jewish Appeal. Frances Garfinkel was also an active member, and in 1992 she became the congregation’s first female president. Both families’ children remain active in the Petersburg congregation.

In November 1918, six months after the community was scheduled to start building, World War I came to an end and soldiers began to evacuate Camp Lee. Although the base remained open as an out-processing center for two years, officially closing in 1921, the city of Hopewell essentially shut down immediately after the war when DuPont closed its guncotton manufacturing plant. As a result, merchants and former employees left the city in droves, and Hopewell became a ghost town—but only briefly. In 1923, another large manufacturer, Tubize Corporation (later acquired by Firestone Tire and Rubber Company), established an artificial silk plant on DuPont’s old site in Hopewell, once again bringing employment and economic activity to the town.

Within a few years of Tubize’s arrival, a new wave of Jewish merchants began to settle in Hopewell to cater to the plant’s employees. Once again, many quickly gained prominence in business and civic affairs. A.A. Spiegel, for instance, owned Broadway Quality Shop, and also served as Vice President of the Retail Merchant Association. Down the street on Broadway Avenue, Austrian immigrant Saul Bisger owned and operated Saul’s Style Shop. Bisger was also an active member of the DuPont Lodge, Kiwanis Club, and the Knights of Pythias. Meanwhile, the Garfinkel brothers—among the only merchants to survive the economic downturn after DuPont’s close—continued to expand their business as women’s clothing retailers in the mid-1920s. Samuel Garfinkel, additionally, opened a grocery store downtown.

By 1929, although the Hopewell Hebrew Congregation remained listed in the City Directory—along with about 10 Jewish-owned businesses—religious activity appears to have greatly slowed. There is no evidence that the congregation ever hired a rabbi, nor did they purchase land for a cemetery. Hopewell’s Jewish residents were usually buried in Petersburg, Richmond, or Washington, D.C.

In 1934, the Tubize-Chatillon company closed their plant in Hopewell in response to declining profits and workers’ attempts to unionize. The closure left about 2,600 employees jobless. Although other manufacturing plants had since arrived in the city—most notably, Allied Chemical and Hercules Chemical—Hopewell’s growth slowed after its short boom in the mid-1920s. By 1937, only about 50 Jews lived in Hopewell, and there was no longer any active religious congregation. Instead, Jewish residents began to join congregations in Petersburg and Washington, D.C. The merchant Saul Bisger, for instance, was an active member of Brith Achim, the Conservative congregation in Petersburg, just 10 miles away, until he died in 1946. Meanwhile, Harry Abrams, a well-known Hopewell merchant, joined D.C.’s Washington Hebrew Congregation.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Jewish population of Hopewell dwindled to only about eight Jewish families, including the Goldbergs, Gordons, Goodmans, Garfinkels, Sellingers, Marks, Sears, and Abrams. Many of these residents had grown up in Hopewell and continued their families’ legacy as active civic and business leaders. In 1962, Sol Goodman, son of John P. Goodman, assumed his father’s position as Commonwealth Attorney. He also served on the City Council for eleven years. Seymour Garfinkel took over his father’s business as co-owner of Garfinkel’s Ladies’Apparel on Broadway Street, which later moved to Cavalier Square. Before closing in 1997, Garfinkel’s was recognized as the Tri-City area’s third-oldest store and one of the earliest to offer charge accounts to customers. Moreover, Seymour Garfinkel is said to have been the first white retailer in Hopewell to hire an African American employee in the 1960s. During his 35 years managing the store, Seymour also served as president of the Retail Merchants Association and the Chamber of Commerce.

By the early 1970s, Hopewell witnessed another population decline, largely due to continuing plant closures and middle class movement to the Prince George and Chesterfield suburbs. The city’s Jewish population, too, continued to decrease, as no new families moved to the area. Nevertheless, one Jewish group in Hopewell was able to remain alive during these decades: the Jewish Women’s Club. Helene Goodman, wife of the prominent attorney John P. Goodman, served as one of the group’s founding members and later as president. Frances Garfinkel, wife of Seymour and co-owner of Garfinkel’s Ladies Apparel, also served as the club’s president. The group, though very small, continued to meet until the late 1970s.

Meanwhile, the few remaining Jewish families in Hopewell joined Petersburg’s Conservative Congregation Brith Achim. Some grew very involved. In 1975, Sol Goodman served as president of the congregation. Seymour Garfinkel also served as a board member and vice president of Brith Achim, as well as chairman of the Tri-City Jewish Appeal. Frances Garfinkel was also an active member, and in 1992 she became the congregation’s first female president. Both families’ children remain active in the Petersburg congregation.

The Jewish Community in Hopewell Today

Today, the Tri-City area of Petersburg, Hopewell, and Colonial Heights has about 200 Jewish residents in total, most of whom are retired merchants or working professionals. Congregation Brith Achim continues to be the only synagogue in the region, led by Rabbi Dennis Beck-Berman. In the past decade, as Hopewell’s overall population has declined, so too has its Jewish community. Today, as the city nears the 100th anniversary of its first Jewish settlers, only a few Jewish residents remain.