Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Lynchburg, Virginia

Lynchburg: Historical Overview

|

John Lynch came to the banks of the James River in 1757 to establish a ferry service to the colonial trading village of New London. By the close of the Revolutionary War, the ferry crossing sprouted into the flourishing commercial center of Lynch’s Ferry. In 1786, the General Assembly of Virginia granted a charter and the ferry post was renamed Lynchburg.

Lynchburg has gained fame as the headquarters of evangelical pastor Jerry Falwell and his flagship college, Liberty University. Long before Falwell and his “Moral Majority” became political and cultural power brokers, Jewish life flourished for a century in central Virginia’s epicenter of regional manufacturing and higher education. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Lynchburg

Nathaniel Guggenheimer

Nathaniel Guggenheimer

Early Settlers

Samuel Saul is considered the first Jewish resident and is listed as paying taxes in Lynchburg in 1790. The next known Jewish settler, Thomas Cohen, opened a store at Eighth and Main Street in 1808. Dozens of businesses like Cohen’s blacksmith and watchmaking shop popped up to cater to the booming tobacco industry. During the War of 1812, Cohen enlisted with the Lynchburg Rifles. A steady stream of Jewish merchants followed Saul and Cohen to Lynchburg over the next 30 years. Samuel Davidson owned a hat manufacturing company in 1814. In the 1830s Michael Hart and silversmith Joseph Cohen, unrelated to Thomas Cohen, both settled in town. Isadore Untermeyer and Nathaniel Guggenheimer opened a dry goods and wholesale store at the corner of Sixth and Main Streets in 1842. Ten years later, Michael Hart and William Moses were listed as the proprietors of the Hart & Moses clothing store. The first record of religious life date back to 1853 when Lynchburg Jews held High Holiday services. The Mayer, Guggenheimer, Moses, Abraham, and Untermeyer families made up the majority of the worshipers.

With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Lynchburg’s nascent Jewish community threw its full support behind the Confederacy. Over a dozen Jewish men joined the roughly 155,000 Virginians in the conflict, fighting in the 2nd, 11th, and 13th Virginia Cavalry and Artillery Companies. Joseph Cohn fought at Antietam as a member of the 13th Battalion’s Virginia Light Artillery and became a lieutenant after sustaining wounds at Petersburg. The Bachrach brothers were killed in combat and are buried at Richmond’s Hebrew Confederate Cemetery.

Following the Civil War, the returning soldiers formed the Hebrew Benevolent Society and prayed at Solomon Goodman’s house. Maurice Guggenheimer, Max Guggenheimer Jr., J. Abrahams, and Charles Burk were the leaders of the new organization. The fledgling group fiercely debated how to conduct services, sparring over whether to maintain traditional Orthodox practices or embrace Reform customs. Sometime later, Lynchburg Jews founded a congregation named Gates of Prayer. According to the 1881 city directory, the congregation met in the Odd Fellow’s Hall, with merchant J. Bamberger serving as lay leader and Fred Myers as president. By 1885, the congregation, still led by Bamberger, was meeting in a building on Church Street. By 1887, the congregation seems to have become defunct, as that year’s city directory noted that Gates of Prayer had “no regular time or place of worship.” Lynchburg Jews wouldn’t establish another formal congregation until 1897.

Samuel Saul is considered the first Jewish resident and is listed as paying taxes in Lynchburg in 1790. The next known Jewish settler, Thomas Cohen, opened a store at Eighth and Main Street in 1808. Dozens of businesses like Cohen’s blacksmith and watchmaking shop popped up to cater to the booming tobacco industry. During the War of 1812, Cohen enlisted with the Lynchburg Rifles. A steady stream of Jewish merchants followed Saul and Cohen to Lynchburg over the next 30 years. Samuel Davidson owned a hat manufacturing company in 1814. In the 1830s Michael Hart and silversmith Joseph Cohen, unrelated to Thomas Cohen, both settled in town. Isadore Untermeyer and Nathaniel Guggenheimer opened a dry goods and wholesale store at the corner of Sixth and Main Streets in 1842. Ten years later, Michael Hart and William Moses were listed as the proprietors of the Hart & Moses clothing store. The first record of religious life date back to 1853 when Lynchburg Jews held High Holiday services. The Mayer, Guggenheimer, Moses, Abraham, and Untermeyer families made up the majority of the worshipers.

With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Lynchburg’s nascent Jewish community threw its full support behind the Confederacy. Over a dozen Jewish men joined the roughly 155,000 Virginians in the conflict, fighting in the 2nd, 11th, and 13th Virginia Cavalry and Artillery Companies. Joseph Cohn fought at Antietam as a member of the 13th Battalion’s Virginia Light Artillery and became a lieutenant after sustaining wounds at Petersburg. The Bachrach brothers were killed in combat and are buried at Richmond’s Hebrew Confederate Cemetery.

Following the Civil War, the returning soldiers formed the Hebrew Benevolent Society and prayed at Solomon Goodman’s house. Maurice Guggenheimer, Max Guggenheimer Jr., J. Abrahams, and Charles Burk were the leaders of the new organization. The fledgling group fiercely debated how to conduct services, sparring over whether to maintain traditional Orthodox practices or embrace Reform customs. Sometime later, Lynchburg Jews founded a congregation named Gates of Prayer. According to the 1881 city directory, the congregation met in the Odd Fellow’s Hall, with merchant J. Bamberger serving as lay leader and Fred Myers as president. By 1885, the congregation, still led by Bamberger, was meeting in a building on Church Street. By 1887, the congregation seems to have become defunct, as that year’s city directory noted that Gates of Prayer had “no regular time or place of worship.” Lynchburg Jews wouldn’t establish another formal congregation until 1897.

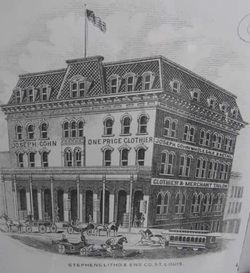

Joseph Cohn's clothing store

Joseph Cohn's clothing store

Lynchburg’s Jewish Civil War veterans quickly transitioned from the battlefield to the front lines of retailing. Joseph Cohn opened a popular clothing store and became such a revered figure in Lynchburg that a local historian wrote that to “have paid a visit to Lynchburg and not called in at Cohn’s would be like visiting Washington and not going to see the Capitol.” Max Guggenheimer, Jr. took over his uncle Nathaniel Guggenheimer’s store in 1866. Max drew on his experience in dry goods and wholesaling to become an early investor in the Witt & Watkins Shoe Company in 1878 and the Craddock-Terry Shoe Company in 1888. The Craddock-Terry Shoe Company was Lynchburg’s largest manufacturer and employer for a majority of the 20th century. His business interests eventually grew beyond retail and shoe manufacturing to textiles. He started the Lynchburg Cotton Mill in 1888 and was its first president. The mill employed 750 workers by the late 1890s and grew to 1,200 employees by the mid-20th century.

By the time of his death in 1912, Guggenheimer was one of the Hill City’s most revered citizens. He was elected to the city council in 1879, where he helped create public schools and paved streets. Max’s cousin, Charles Guggenheimer opened his own store with two investors at Ninth and Main Street in 1885. Charles would eventually split with his partners and own a series of stores. His final store, Guggenheimer’s, opened at Seventh and Main Street in 1928 and remained in business until 1961.

While the Guggenheimers and Cohns established themselves as titans of their respective industries, Louis Lazarus staked out his spot as the town’s leading liquor merchant. A veteran of Philadelphia’s liquor industry, Lazarus returned in 1886 and opened a liquor wholesaling company at 818 Main Street. Lazarus and his partner, M. Goodman a former mayor of Pocahontas, Virginia, used Lynchburg as their base to establish a distribution empire that fanned into several states.

By the time of his death in 1912, Guggenheimer was one of the Hill City’s most revered citizens. He was elected to the city council in 1879, where he helped create public schools and paved streets. Max’s cousin, Charles Guggenheimer opened his own store with two investors at Ninth and Main Street in 1885. Charles would eventually split with his partners and own a series of stores. His final store, Guggenheimer’s, opened at Seventh and Main Street in 1928 and remained in business until 1961.

While the Guggenheimers and Cohns established themselves as titans of their respective industries, Louis Lazarus staked out his spot as the town’s leading liquor merchant. A veteran of Philadelphia’s liquor industry, Lazarus returned in 1886 and opened a liquor wholesaling company at 818 Main Street. Lazarus and his partner, M. Goodman a former mayor of Pocahontas, Virginia, used Lynchburg as their base to establish a distribution empire that fanned into several states.

Elias Schewel

Elias Schewel

By 1899, Jewish merchants dominated the retail industry in Lynchburg. The town’s Jewish-owned clothing stores, I. Jacobs, A. Kaplan, J. Lichtenstein, M. Rosenthal. M. Switzer, M. Schaffer, and Joseph Cohn’s and Sons, made up half of the town’s clothing stores. Outside of clothing, R. Eichelbaum had a junk company, W. Levin had a fabric and craft shop, Harry Hirsh dealt in men’s furnishings, and Jacob and Lena Oppleman owned the L. Oppleman Pawn Shop.

Unlike many Lynchburg Jews, Elias Schewel had no intention of going into retail when he moved to town. Trained as a rabbi in Latvia, Schewel moved to Lynchburg in 1889 to serve as the town’s rabbi, shochet (kosher butcher), and teacher but quickly realized he would be unable to support his family on his paltry salary. To supplement his income, he peddled pots, pans, and picture frames. The rabbi turned merchant was prosperous and eventually expanded into neighboring counties. In 1897, Schewel opened The Chicago Furniture Bargain House, later renamed Schewel’s Furniture Company. Under the leadership of Schewel and his sons, the company would rise to become a regional furniture giant.

Unlike many Lynchburg Jews, Elias Schewel had no intention of going into retail when he moved to town. Trained as a rabbi in Latvia, Schewel moved to Lynchburg in 1889 to serve as the town’s rabbi, shochet (kosher butcher), and teacher but quickly realized he would be unable to support his family on his paltry salary. To supplement his income, he peddled pots, pans, and picture frames. The rabbi turned merchant was prosperous and eventually expanded into neighboring counties. In 1897, Schewel opened The Chicago Furniture Bargain House, later renamed Schewel’s Furniture Company. Under the leadership of Schewel and his sons, the company would rise to become a regional furniture giant.

Agudath Sholom's first synagogue

Agudath Sholom's first synagogue

Organized Jewish Life in Lynchburg

A splash of the tidal wave of Eastern European Jewish immigrants that landed in the United States in the 1890s played an instrumental role in the creation of Lynchburg’s first congregation. On November 28, 1897, a group of Jews, most of whom were immigrants, gathered above Moses Rosenthal’s furniture store at 217 Twelfth Street to discuss fundraising for a Torah and locations to hold services. A week later, 23 founding members of the Agudas Achim congregation elected J.W. Lichtenstein as their president. In January 1898, the infant congregation moved into a temporary home above Lichtenstein’s store.

The euphoria of Agudas Achim’s establishment was short lived. Rosenthal and 11 other charter members left the congregation on January 23,1898, roughly five weeks after the congregation’s formation. Their names were promptly deleted from the charter roll. The cause of the split is unknown, though it is thought the fissure was caused over differing opinions over religious practice. Rosenthal and the other breakaways quickly formed Ahavoth Sholom congregation which lasted approximately one year. The two congregations merged in February 1899 to form Agudath Sholom congregation.

In the early years of the congregation, Elias Schewel used his rabbinical training, serving as the spiritual leader of the growing community which would climb to 250 people by 1907. Schewel led services until the hiring of Rabbi S.B. Schein in 1903. That same year, the congregation purchased the First Christian Church at 513 Church Street, which they used as a synagogue for the next 50 years. In 1905, the women of Agudath Sholom established the Ladies Auxiliary Society with Sarah Lichtenstein as the first president. In 1910, the congregation purchased a cemetery on the other side of the James River in Madison Heights.

A splash of the tidal wave of Eastern European Jewish immigrants that landed in the United States in the 1890s played an instrumental role in the creation of Lynchburg’s first congregation. On November 28, 1897, a group of Jews, most of whom were immigrants, gathered above Moses Rosenthal’s furniture store at 217 Twelfth Street to discuss fundraising for a Torah and locations to hold services. A week later, 23 founding members of the Agudas Achim congregation elected J.W. Lichtenstein as their president. In January 1898, the infant congregation moved into a temporary home above Lichtenstein’s store.

The euphoria of Agudas Achim’s establishment was short lived. Rosenthal and 11 other charter members left the congregation on January 23,1898, roughly five weeks after the congregation’s formation. Their names were promptly deleted from the charter roll. The cause of the split is unknown, though it is thought the fissure was caused over differing opinions over religious practice. Rosenthal and the other breakaways quickly formed Ahavoth Sholom congregation which lasted approximately one year. The two congregations merged in February 1899 to form Agudath Sholom congregation.

In the early years of the congregation, Elias Schewel used his rabbinical training, serving as the spiritual leader of the growing community which would climb to 250 people by 1907. Schewel led services until the hiring of Rabbi S.B. Schein in 1903. That same year, the congregation purchased the First Christian Church at 513 Church Street, which they used as a synagogue for the next 50 years. In 1905, the women of Agudath Sholom established the Ladies Auxiliary Society with Sarah Lichtenstein as the first president. In 1910, the congregation purchased a cemetery on the other side of the James River in Madison Heights.

Rev. Simon Cagan,

Rev. Simon Cagan, Agudath Sholom's shochet and chazzan

Schism struck the Lynchburg Jewish community once again in 1909 when another congregation, named Beth Joseph, was established. In 1913, a group of disgruntled Agudath Sholom members left the congregation, taking the Torah, and joined Beth Joseph. That year, Beth Joseph met in a building on Church Street with Rev. David Somers as its spiritual leader. The dispute continued for several years until 1915, when both congregations agreed to a rabbinic court of mediation. Soon after, they reunited under the name Agudath Sholom. After the merger, their two contiguous cemeteries were joined and renamed the Beth Joseph-Agudath Sholom Cemetery. The now unified congregation hired David Somers to lead services and also serve as shochet and mohel. By 1919, Agudath Sholom had 50 members with 50 children in its religious school.

The steady growth of the Jewish community during the first decades of the 20th century prompted Agudath Sholom to try to expand their building in the early 1920s. Though the congregation received financial contributions from 44 of the synagogue’s 52 families, it was not enough to cover building costs. Congregation President Abe Schewel turned to help from the local Christian community. Schewel’s impassioned plea stirred the Christian community and led to 112 donations that helped the congregation cover the remaining costs of the addition. On October 5, 1924, the congregation dedicated the new two-story Jewish Community Center. The new two-level addition allowed Agudath Sholom to accommodate the synagogue’s Orthodox and Conservative factions as each group now had its own area for worship. Nevertheless, there was still conflict between the two groups. Debate erupted over the presence of a mikvah (ritual bath). Reform leaning congregants opposed the mikvah, while a more traditional faction wanted it. C. M. Guggenheimer was so disgusted with the mikvah he resigned as chairman of the building and finance committee.

Despite this conflict, Agudath Sholom was able to hire a series of rabbis in the 1920s and 30s, most of whom left after only a short period. They enjoyed greater stability with their reverends, hiring Simon Cagan in 1923 as shochet, teacher, and service leader. Cagan remained with the congregation until 1946.

The steady growth of the Jewish community during the first decades of the 20th century prompted Agudath Sholom to try to expand their building in the early 1920s. Though the congregation received financial contributions from 44 of the synagogue’s 52 families, it was not enough to cover building costs. Congregation President Abe Schewel turned to help from the local Christian community. Schewel’s impassioned plea stirred the Christian community and led to 112 donations that helped the congregation cover the remaining costs of the addition. On October 5, 1924, the congregation dedicated the new two-story Jewish Community Center. The new two-level addition allowed Agudath Sholom to accommodate the synagogue’s Orthodox and Conservative factions as each group now had its own area for worship. Nevertheless, there was still conflict between the two groups. Debate erupted over the presence of a mikvah (ritual bath). Reform leaning congregants opposed the mikvah, while a more traditional faction wanted it. C. M. Guggenheimer was so disgusted with the mikvah he resigned as chairman of the building and finance committee.

Despite this conflict, Agudath Sholom was able to hire a series of rabbis in the 1920s and 30s, most of whom left after only a short period. They enjoyed greater stability with their reverends, hiring Simon Cagan in 1923 as shochet, teacher, and service leader. Cagan remained with the congregation until 1946.

Abe Schewel

Abe Schewel

The Great Depression

The Depression brought the growth of Agudath Sholom to a screeching stop. Only one-third of congregants could pay their dues as attendance lagged at synagogue functions. The congregation was unable to afford a full-time rabbi from 1931 to 1936 and the building faced foreclosure after several missed mortgage payments. Abe Cohen led the effort to restructure the debt and helped the congregation avert financial ruin. By the mid-1930s, Agudath Sholom regained its footing. In 1936, they hired Rabbi Isadore Franzblau, who led Agudath Sholom for the next six years until he left to become a military chaplain. Reared in Reform Judaism during his European upbringing, Franzblau instituted changes such as the introduction of the Reform prayer book in 1939. The embrace of Reform practices was driven by Franzblau’s belief that services should cater toward the largest amount of people. Despite the introduction of the Reform prayer book, Agudath Sholom would not join the Union of American Hebrew Congregations until the mid-1960s.

Fighting Discrimination

While Lynchburg Jews played leading roles in civic life, they also sometimes became outspoken voices against racial discrimination. Abe Schewel, who was elected to the city council in 1934, fought against the city’s segregation laws as chairman of the Interracial Commission. He challenged the city’s use of public funds for street, water, and sewer repairs in subdivisions that discriminated based on race or religion. In June 1936, Schewel sought an indefinite excusal from votes concerning the use of government money for restricted subdivisions. According to the local newspaper, Schewel viewed the city practice as “morally wrong” and hoped that his “silent reproach or rebuke” would whittle away the segregationist feelings in the town. Schewel was respected in the local African American community for providing employment to African Americans at his furniture store, especially during the Great Depression when many Lynchburg businesses fired African American employees and replaced them with white workers. Schewel Furniture Company was also one of two local white-owned businesses to open its restrooms to African Americans. In addition to his city council work, Schewel was president of Agudath Sholom synagogue for 25 years, president of the Fifth District of B’nai Brith and co-founder of the Lynchburg branch of the Round Table Conference of Christians and Jews.

Despite their commercial success and numerous civic contributions, the Jews of Lynchburg did encounter occasional anti-Semitism. Max Guggenheimer, Jr. was barred from most civic organizations except the Masons. Until the Great Depression the Boonsboro Country Club banned Jews, but financial problems forced the club to turn to Abe Cohen, who owned a successful scrap iron business, in order to remain solvent. Cohen initially balked at the request, reportedly retorting “Why should I help a club to which I cannot belong?” The board eventually changed their stance and allowed Cohen into the club. Cohen later served as vice-mayor of Lynchburg.

The Depression brought the growth of Agudath Sholom to a screeching stop. Only one-third of congregants could pay their dues as attendance lagged at synagogue functions. The congregation was unable to afford a full-time rabbi from 1931 to 1936 and the building faced foreclosure after several missed mortgage payments. Abe Cohen led the effort to restructure the debt and helped the congregation avert financial ruin. By the mid-1930s, Agudath Sholom regained its footing. In 1936, they hired Rabbi Isadore Franzblau, who led Agudath Sholom for the next six years until he left to become a military chaplain. Reared in Reform Judaism during his European upbringing, Franzblau instituted changes such as the introduction of the Reform prayer book in 1939. The embrace of Reform practices was driven by Franzblau’s belief that services should cater toward the largest amount of people. Despite the introduction of the Reform prayer book, Agudath Sholom would not join the Union of American Hebrew Congregations until the mid-1960s.

Fighting Discrimination

While Lynchburg Jews played leading roles in civic life, they also sometimes became outspoken voices against racial discrimination. Abe Schewel, who was elected to the city council in 1934, fought against the city’s segregation laws as chairman of the Interracial Commission. He challenged the city’s use of public funds for street, water, and sewer repairs in subdivisions that discriminated based on race or religion. In June 1936, Schewel sought an indefinite excusal from votes concerning the use of government money for restricted subdivisions. According to the local newspaper, Schewel viewed the city practice as “morally wrong” and hoped that his “silent reproach or rebuke” would whittle away the segregationist feelings in the town. Schewel was respected in the local African American community for providing employment to African Americans at his furniture store, especially during the Great Depression when many Lynchburg businesses fired African American employees and replaced them with white workers. Schewel Furniture Company was also one of two local white-owned businesses to open its restrooms to African Americans. In addition to his city council work, Schewel was president of Agudath Sholom synagogue for 25 years, president of the Fifth District of B’nai Brith and co-founder of the Lynchburg branch of the Round Table Conference of Christians and Jews.

Despite their commercial success and numerous civic contributions, the Jews of Lynchburg did encounter occasional anti-Semitism. Max Guggenheimer, Jr. was barred from most civic organizations except the Masons. Until the Great Depression the Boonsboro Country Club banned Jews, but financial problems forced the club to turn to Abe Cohen, who owned a successful scrap iron business, in order to remain solvent. Cohen initially balked at the request, reportedly retorting “Why should I help a club to which I cannot belong?” The board eventually changed their stance and allowed Cohen into the club. Cohen later served as vice-mayor of Lynchburg.

The 1940s

While Jews sometimes faced discrimination, Lynchburg served as a refuge for some Jews after World War II. In 1939 Abraham Kreusler was a respected academic in Warsaw, where he ran a junior college and served on an advisory panel for the Polish Ministry of Education. The Nazi invasion sent Kreusler and his family wandering throughout Eastern Europe all the way to the Russian-Kyrgz border before they immigrated to the U.S. and settled in Lynchburg in 1948. Kreusler taught Russian language and literature at Randolph Macon Women’s College until retiring in 1966. Holocaust survivors Walter and Sophie Storozum, natives of Germany, arrived in Lynchburg in the late 1950s and became very active in the community. Walter regularly spoke about his Holocaust experiences at universities, churches, and schools. Ted Brenig came to Lynchburg to work as an engineer for GE in 1961 after living in Switzerland for several years. Born and raised in Vienna, Brenig was separated from his parents while the family was interned in Vichy, France. Brenig was eventually placed in a children’s home in Switzerland, though his parents perished at Auschwitz.

Jewish retailing reached its peak in Lynchburg in the 1940s when over 40 Jewish businesses were located downtown. Schewel’s, M. Rosenthal Furniture, and Coopers Furniture were mainstays in the furniture business. Lichtenstein’s, Kulman’s Snyder & Berman, Guggenheimer, and Joseph Cohn were lynchpins of the clothing industry. In The Agudath Sholom Story: Breaking Apart and Coming Together, longtime congregant Michael Grosman said that during the heyday of Jewish retailing in Lychburg “when all the Jewish-owned stores were closed for High Holy Days, one could toss a stone down Main Street and not hit a single person.”

While Jews sometimes faced discrimination, Lynchburg served as a refuge for some Jews after World War II. In 1939 Abraham Kreusler was a respected academic in Warsaw, where he ran a junior college and served on an advisory panel for the Polish Ministry of Education. The Nazi invasion sent Kreusler and his family wandering throughout Eastern Europe all the way to the Russian-Kyrgz border before they immigrated to the U.S. and settled in Lynchburg in 1948. Kreusler taught Russian language and literature at Randolph Macon Women’s College until retiring in 1966. Holocaust survivors Walter and Sophie Storozum, natives of Germany, arrived in Lynchburg in the late 1950s and became very active in the community. Walter regularly spoke about his Holocaust experiences at universities, churches, and schools. Ted Brenig came to Lynchburg to work as an engineer for GE in 1961 after living in Switzerland for several years. Born and raised in Vienna, Brenig was separated from his parents while the family was interned in Vichy, France. Brenig was eventually placed in a children’s home in Switzerland, though his parents perished at Auschwitz.

Jewish retailing reached its peak in Lynchburg in the 1940s when over 40 Jewish businesses were located downtown. Schewel’s, M. Rosenthal Furniture, and Coopers Furniture were mainstays in the furniture business. Lichtenstein’s, Kulman’s Snyder & Berman, Guggenheimer, and Joseph Cohn were lynchpins of the clothing industry. In The Agudath Sholom Story: Breaking Apart and Coming Together, longtime congregant Michael Grosman said that during the heyday of Jewish retailing in Lychburg “when all the Jewish-owned stores were closed for High Holy Days, one could toss a stone down Main Street and not hit a single person.”

Agudath Sholom's 1957 synagogue

Agudath Sholom's 1957 synagogue

The Post-War Years

One hundred years after Union troops swept through Lynchburg in a failed attempt to destroy its canals and rail lines, a new batch of Northerners descended upon the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains during Lynchburg’s “Second Northern Invasion.” This time the “Northern invaders” were manufacturing companies that helped transform the Lynchburg economy. Jewish owned businesses Dixie Garment, C.B. Cones, Blue Buckle Overalls, Art Nitewear, and Garlin Manufacturing combined to pour 2,000 jobs into the area. This Northern influx caused a spike in the Jewish community as the community grew from 250 people in 1947 to 350 by 1960, creating a need for a larger synagogue. After five years of raising money from synagogue members and the non-Jewish community, Agudath Sholom held its first services in its newly constructed building on Rosh Hashanah in 1957. The building frenzy continued the next few years as the congregation installed a mosaic in 1961 and added religious school classrooms in the basement.

The post-war years saw a flurry of Jewish activity. The religious school was bursting with 125 students and the local chapter of the Reform movement’s National Federation of Temple Youth was vibrant. Rae Schewel restarted a Hadassah branch in 1945 that grew to include both Jewish and non-Jewish members.

One hundred years after Union troops swept through Lynchburg in a failed attempt to destroy its canals and rail lines, a new batch of Northerners descended upon the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains during Lynchburg’s “Second Northern Invasion.” This time the “Northern invaders” were manufacturing companies that helped transform the Lynchburg economy. Jewish owned businesses Dixie Garment, C.B. Cones, Blue Buckle Overalls, Art Nitewear, and Garlin Manufacturing combined to pour 2,000 jobs into the area. This Northern influx caused a spike in the Jewish community as the community grew from 250 people in 1947 to 350 by 1960, creating a need for a larger synagogue. After five years of raising money from synagogue members and the non-Jewish community, Agudath Sholom held its first services in its newly constructed building on Rosh Hashanah in 1957. The building frenzy continued the next few years as the congregation installed a mosaic in 1961 and added religious school classrooms in the basement.

The post-war years saw a flurry of Jewish activity. The religious school was bursting with 125 students and the local chapter of the Reform movement’s National Federation of Temple Youth was vibrant. Rae Schewel restarted a Hadassah branch in 1945 that grew to include both Jewish and non-Jewish members.

Rabbi Ephraim Fischoff

Rabbi Ephraim Fischoff

Beginning with the acceptance of women as full members in 1949, the congregation gradually shifted toward the Reform movement. In 1950 the congregation wrote in its bylaws that all forms of Jewish worship were to be tolerated cementing Agudath Sholom’s embrace of liberal religious practices. By the mid-1950s, the congregation’s Orthodox contingent withered away. Agudath Sholom formalized its relationship with the Reform movement when it joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1966. Affiliation with the UAHC was the idea of Rabbi Ephraim Fischoff. Fischoff spent 11 years in Lynchburg and became a prominent community member. He lectured at local colleges and ran a popular Great Books course. Following Fischoff’s departure, a number of rabbis served Agudath Sholom for brief tenures before the arrival of Rabbi Morris Shapiro in 1976. Shapiro remained for 14 years and was an active lecturer at area colleges and had close relationships with the town’s Christian clergy.

The Late 20th Century

Thirty years after women had been granted full membership privileges, Rosel Schewel became Agudath Sholom’s first female president, serving from 1980 to 1983. Schewel was one half of a Lynchburg power couple. Her husband Elliot Schewel followed his father Abe Schewel into politics when he was elected a Virginia State Senator in 1976. Schewel was an influential moderate Democrat respected by various constituencies. An article in the Lynchburg News in 1982 declared that Schewel “may be the most popular person in town” with one local official stating “even the Republicans hate to vote against him.” Schewel retired from the State Senate in 1996.

By 1982, Agudath Sholom had reached a peak of 109 contributing members. After Rabbi Shapiro’s retirement in 1990, Hollis Seidner served the congregation for two years. In 1992, they hired Rabbi Tom Gutherz, who had just been ordained by Hebrew Union College. Rabbi Gutherz led the congregation until 2005. Rabbi Annette Koch followed next, coming twice a month from Philadelphia.

The Late 20th Century

Thirty years after women had been granted full membership privileges, Rosel Schewel became Agudath Sholom’s first female president, serving from 1980 to 1983. Schewel was one half of a Lynchburg power couple. Her husband Elliot Schewel followed his father Abe Schewel into politics when he was elected a Virginia State Senator in 1976. Schewel was an influential moderate Democrat respected by various constituencies. An article in the Lynchburg News in 1982 declared that Schewel “may be the most popular person in town” with one local official stating “even the Republicans hate to vote against him.” Schewel retired from the State Senate in 1996.

By 1982, Agudath Sholom had reached a peak of 109 contributing members. After Rabbi Shapiro’s retirement in 1990, Hollis Seidner served the congregation for two years. In 1992, they hired Rabbi Tom Gutherz, who had just been ordained by Hebrew Union College. Rabbi Gutherz led the congregation until 2005. Rabbi Annette Koch followed next, coming twice a month from Philadelphia.

The Jewish Community in Lynchburg Today

Lynchburg Mayor Michael Gillette

Lynchburg Mayor Michael Gillette

By 2013, Agudath Sholom had shrunk to 76 member families, though it maintained an active religious school. One of the reasons for the decline in membership was a schism that occurred in the mid-2000s that led to several members leaving the congregation and creating Chavurah Masarti. The chavurah remained active in 2013, meeting twice a month.

Like many Jewish communities in the South, Lynchburg’s Jewish community has shrunk over the second half of the 20th century. Few of the baby boomers raised in Lynchburg returned to the city after college making it difficult to replenish the Jewish population. The days of downtown being closed on the High Holidays are a distant memory as only three Jewish-owned retail businesses, Schewel Furniture Company, L. Oppleman Pawn Shop, and Commercial Glass & Plastics owned by Robert Hiller, remain in operation. Though Jewish retailing has declined, the tradition of Jewish involvement in civic affairs remains strong. In July 2012, Michael Gillette was appointed mayor, making him Lynchburg’s first Jewish mayor. With a solid mix of professionals, academics, and a few remaining merchants, Jewish life in Lynchburg remains strong, though internal division remains a challenge for the community.

Like many Jewish communities in the South, Lynchburg’s Jewish community has shrunk over the second half of the 20th century. Few of the baby boomers raised in Lynchburg returned to the city after college making it difficult to replenish the Jewish population. The days of downtown being closed on the High Holidays are a distant memory as only three Jewish-owned retail businesses, Schewel Furniture Company, L. Oppleman Pawn Shop, and Commercial Glass & Plastics owned by Robert Hiller, remain in operation. Though Jewish retailing has declined, the tradition of Jewish involvement in civic affairs remains strong. In July 2012, Michael Gillette was appointed mayor, making him Lynchburg’s first Jewish mayor. With a solid mix of professionals, academics, and a few remaining merchants, Jewish life in Lynchburg remains strong, though internal division remains a challenge for the community.