Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk: Historical Overview

|

Located at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, Norfolk, Virginia, has been an important trading center since its founding in 1682. By 1775, Norfolk was Virginia’s most prosperous town, though its destruction by the British in 1776 slowed its growth. In 1790, about 3,000 people lived in the town, although that figure would double over the next decade. After independence, Norfolk offered enough economic opportunity to attract a handful of Jewish merchants who set up trading businesses in Virginia’s largest port city.

Jews have lived in Norfolk since the 18th century, and Norfolk has been home to a Jewish community for nearly two centuries. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Norfolk

Aaron Goldsmith and wife Caroline.

Aaron Goldsmith and wife Caroline. Photo courtesy of Ohef Sholom Archives.

Early Settlers

The first Jews in Norfolk were Moses and Eliza Myers, who arrived in 1787. Moses was born in New York, where he had become a partner in a trans-Atlantic trading firm. After opening an office in Amsterdam, Myers returned to America after the business failed. He decided to settle in Norfolk with his new bride Eliza and opened a small store selling naval supplies, corn, animal hides, tobacco, and lumber. From this humble beginning, Myers’ business thrived, growing into a major import-export operation as Norfolk emerged as a significant port in the early republic era. According to historian Malcolm Stern, Myers “had dealings in practically every sea port on both sides of the North Atlantic.” Myers became one of Norfolk’s most prominent businessmen and early civic leaders. In 1792, he became superintendent of the Norfolk branch of the Bank of Richmond. Myers was elected to Norfolk’s Common Council in 1795, serving as president of the body since he had received the most votes. Myers’ economic fortunes turned in the 1810s as a result of the British blockade and the failure of the First National Bank in 1819. While Myers had to declare bankruptcy, he was later appointed by President John Quincy Adams to serve as collector of the port of Norfolk in 1827. Today, the home he and Eliza built is a house museum administered by the Chrysler Museum of Art.

In the early decades of the 19th century, a handful of other Jews settled in Norfolk. When Solomon Nones died in 1819, the small Norfolk Jewish community, led by Myers and Philip Cohen, who had married Myers’ daughter Augusta, bought a plot of land from Solomon Marks for use as a Jewish cemetery. There is no evidence of any other religious activities of these early Norfolk Jews, although since they numbered more than ten men, they may have held occasional prayer services. This early period of Norfolk Jewish history is largely disconnected from the later development of the Jewish community. Due to intermarriage, most of the grandchildren of Moses and Eliza Myers and of other early settlers were not Jewish. The city’s first Jewish cemetery remained small, with only about a dozen graves, which were later moved to Norfolk’s larger Jewish cemetery that was established in 1850.

The first Jews in Norfolk were Moses and Eliza Myers, who arrived in 1787. Moses was born in New York, where he had become a partner in a trans-Atlantic trading firm. After opening an office in Amsterdam, Myers returned to America after the business failed. He decided to settle in Norfolk with his new bride Eliza and opened a small store selling naval supplies, corn, animal hides, tobacco, and lumber. From this humble beginning, Myers’ business thrived, growing into a major import-export operation as Norfolk emerged as a significant port in the early republic era. According to historian Malcolm Stern, Myers “had dealings in practically every sea port on both sides of the North Atlantic.” Myers became one of Norfolk’s most prominent businessmen and early civic leaders. In 1792, he became superintendent of the Norfolk branch of the Bank of Richmond. Myers was elected to Norfolk’s Common Council in 1795, serving as president of the body since he had received the most votes. Myers’ economic fortunes turned in the 1810s as a result of the British blockade and the failure of the First National Bank in 1819. While Myers had to declare bankruptcy, he was later appointed by President John Quincy Adams to serve as collector of the port of Norfolk in 1827. Today, the home he and Eliza built is a house museum administered by the Chrysler Museum of Art.

In the early decades of the 19th century, a handful of other Jews settled in Norfolk. When Solomon Nones died in 1819, the small Norfolk Jewish community, led by Myers and Philip Cohen, who had married Myers’ daughter Augusta, bought a plot of land from Solomon Marks for use as a Jewish cemetery. There is no evidence of any other religious activities of these early Norfolk Jews, although since they numbered more than ten men, they may have held occasional prayer services. This early period of Norfolk Jewish history is largely disconnected from the later development of the Jewish community. Due to intermarriage, most of the grandchildren of Moses and Eliza Myers and of other early settlers were not Jewish. The city’s first Jewish cemetery remained small, with only about a dozen graves, which were later moved to Norfolk’s larger Jewish cemetery that was established in 1850.

Moses & Eliza Myers

Moses & Eliza Myers

Organized Jewish Life in Norfolk

Not until the arrival of immigrants from the German states in the 1840s did Jews establish lasting communal institutions in Norfolk. Jacob Umstadter came to Norfolk from Hesse in 1844. He soon began leading services and serving as a shochet (kosher butcher) for Norfolk’s small Jewish community. In 1848, the group acquired a Torah from Baltimore and formed Congregation House of Jacob. Aaron Goldsmith, who had recently arrived in Norfolk from Baltimore, was the first president of the congregation, which met in various rented rooms in its early years. In 1850, they bought land for a cemetery. While Umstadter served as chazzan (service leader) for House of Jacob after it was founded, by 1852, Rev. Reuben Oppenheimer, who also was a fruit merchant, chanted the Hebrew services. In 1853, at a time when there were no public schools in Norfolk, the congregation opened the Hebrew and English Literary Institute which taught Hebrew and Judaism, as well as secular subjects.

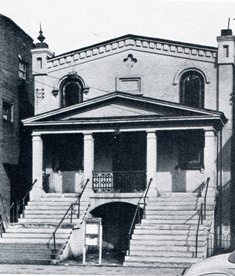

Starting in 1853, the congregation rented the first floor of the Odd Fellows Hall, which they used as a worship space. When the building burned in 1859, they bought a lot on Cumberland Avenue from Jacob Umstadter and built Norfolk’s first synagogue. The building was also used for the Hebrew and English Literary Institute. In fact, in 1860, the building was officially deeded to the school. The congregation remained active, even through the Civil War years. According to the 1866 City Directory, Jonas Hecht served as reader for the “Hebrew Synagogue” that held weekly services at 9 am on Saturday mornings. In 1867, the congregation was reorganized and renamed “Ohef Sholom” (Lovers of Peace), an appropriate sentiment in the aftermath of the Civil War. While the Hebrew and English Literary Institute soon ceased to function due to the establishment of public schools in Norfolk, it remained a legal entity which owned Ohef Sholom’s building.

When it was founded, Ohef Sholom was an Orthodox congregation. Its 1867 constitution required that its president and vice president be Shabbat observant, while men and women sat separately in the synagogue. Ohef Sholom also employed shochets so members could follow the Jewish dietary laws. Yet a growing number of members began to advocate changes in the congregation’s ritual, calling for mixed seating, more German rather than Hebrew in the service, and the use of an organ. In 1869, a ritual reform committee was established, which led to bitter debate within the congregation. The board had to institute a new rule fining members for using personal attacks during these discussions. A group of traditional members, led by Jacob Umstadter, began to withhold their dues in protest of these proposed changes.

Not until the arrival of immigrants from the German states in the 1840s did Jews establish lasting communal institutions in Norfolk. Jacob Umstadter came to Norfolk from Hesse in 1844. He soon began leading services and serving as a shochet (kosher butcher) for Norfolk’s small Jewish community. In 1848, the group acquired a Torah from Baltimore and formed Congregation House of Jacob. Aaron Goldsmith, who had recently arrived in Norfolk from Baltimore, was the first president of the congregation, which met in various rented rooms in its early years. In 1850, they bought land for a cemetery. While Umstadter served as chazzan (service leader) for House of Jacob after it was founded, by 1852, Rev. Reuben Oppenheimer, who also was a fruit merchant, chanted the Hebrew services. In 1853, at a time when there were no public schools in Norfolk, the congregation opened the Hebrew and English Literary Institute which taught Hebrew and Judaism, as well as secular subjects.

Starting in 1853, the congregation rented the first floor of the Odd Fellows Hall, which they used as a worship space. When the building burned in 1859, they bought a lot on Cumberland Avenue from Jacob Umstadter and built Norfolk’s first synagogue. The building was also used for the Hebrew and English Literary Institute. In fact, in 1860, the building was officially deeded to the school. The congregation remained active, even through the Civil War years. According to the 1866 City Directory, Jonas Hecht served as reader for the “Hebrew Synagogue” that held weekly services at 9 am on Saturday mornings. In 1867, the congregation was reorganized and renamed “Ohef Sholom” (Lovers of Peace), an appropriate sentiment in the aftermath of the Civil War. While the Hebrew and English Literary Institute soon ceased to function due to the establishment of public schools in Norfolk, it remained a legal entity which owned Ohef Sholom’s building.

When it was founded, Ohef Sholom was an Orthodox congregation. Its 1867 constitution required that its president and vice president be Shabbat observant, while men and women sat separately in the synagogue. Ohef Sholom also employed shochets so members could follow the Jewish dietary laws. Yet a growing number of members began to advocate changes in the congregation’s ritual, calling for mixed seating, more German rather than Hebrew in the service, and the use of an organ. In 1869, a ritual reform committee was established, which led to bitter debate within the congregation. The board had to institute a new rule fining members for using personal attacks during these discussions. A group of traditional members, led by Jacob Umstadter, began to withhold their dues in protest of these proposed changes.

Rabbi Bernhard Eberson.

Rabbi Bernhard Eberson. Photo courtesy of Ohef Sholom Archives.

When Ohef Sholom voted to move toward Reform Judaism, Umstadter and the traditionalists left the congregation and established Congregation Beth El (House of God) in 1870. This split was initially bitter, as both congregations claimed ownership of the city’s Jewish cemetery. This led to a prolonged legal dispute and an effort by both congregations to block burials of the other’s members. Finally, they agreed to form a new joint entity, the Hebrew Cemetery Company, with three trustees from each congregation to oversee it. This division seemed to carry over to the city’s Jewish fraternal societies. Members of Ohef Sholom founded a B’nai B’rith Lodge in 1871. In 1875, members of Beth El, led by its spiritual leader Rev. S. Mendelsohn, established a lodge of Order Kesher Shel Barzel, a competing fraternal society that, like B’nai B’rith, offered death and sickness benefits.

Although its movement toward Reform had split the Jewish community, Ohef Sholom did not abandon all aspects of traditional Judaism right away. The congregation still employed a shochet in 1873, and an effort to ban head coverings attracted only a few votes in 1876. Ohef Sholom would not join the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, officially affiliating with the Reform Movement, until 1907. Still, they bought an organ in 1870 and by 1871 had removed the requirement that officers be Sabbath observant. In 1876, Ohef Sholom approached Beth El in an attempt to reunite, but was rebuffed. In 1878, Ohef Sholom swapped its building with a Methodist Church, which they dedicated as a synagogue. The congregation hired its first ordained rabbi, Bernard Fould, in 1869. Their first long-serving rabbi was Bernhard Eberson, who led Ohef Sholom from 1877 to 1899. When the congregation struggled during its early years, the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society, which had been founded in 1865, provided financial support, helping to pay the debt on the congregation’s building.

Beth El initially used a building on Fenchurch Street, and soon hired Rev. L. Harfeld as their spiritual leader. Samuel Seldner was the congregation’s first president, serving from 1870 until his death in 1898. The traditional congregation had several short-lived spiritual leaders in its early years. Beth El member Daniel Levy served as chazzan of the congregation from 1880 to 1889. After the Methodist Church defaulted on its mortgage, Beth El was able to buy Ohef Sholom’s former synagogue on Cumberland Street at auction in 1880. They used this building as their synagogue for the next four decades.

Although its movement toward Reform had split the Jewish community, Ohef Sholom did not abandon all aspects of traditional Judaism right away. The congregation still employed a shochet in 1873, and an effort to ban head coverings attracted only a few votes in 1876. Ohef Sholom would not join the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, officially affiliating with the Reform Movement, until 1907. Still, they bought an organ in 1870 and by 1871 had removed the requirement that officers be Sabbath observant. In 1876, Ohef Sholom approached Beth El in an attempt to reunite, but was rebuffed. In 1878, Ohef Sholom swapped its building with a Methodist Church, which they dedicated as a synagogue. The congregation hired its first ordained rabbi, Bernard Fould, in 1869. Their first long-serving rabbi was Bernhard Eberson, who led Ohef Sholom from 1877 to 1899. When the congregation struggled during its early years, the Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Society, which had been founded in 1865, provided financial support, helping to pay the debt on the congregation’s building.

Beth El initially used a building on Fenchurch Street, and soon hired Rev. L. Harfeld as their spiritual leader. Samuel Seldner was the congregation’s first president, serving from 1870 until his death in 1898. The traditional congregation had several short-lived spiritual leaders in its early years. Beth El member Daniel Levy served as chazzan of the congregation from 1880 to 1889. After the Methodist Church defaulted on its mortgage, Beth El was able to buy Ohef Sholom’s former synagogue on Cumberland Street at auction in 1880. They used this building as their synagogue for the next four decades.

David Lowenberg.

David Lowenberg. Photo courtesy of Ohef Sholom Archives.

Jewish Businesses in Norfolk

The members of both Ohef Sholom and Beth El were primarily German immigrants. By 1878, an estimated 500 Jews lived in Norfolk. Most of them were in the retail business, especially in clothing. In 1875, Jews owned 11 of the city’s 18 clothing stores. Both of Norfolk’s wholesale clothing firms, Z. and A. Hofheimer and Lowenburg, Jacobs, and Co., were Jewish owned. The Hofheimer family owned several different businesses in 1875 - in addition to the wholesale clothing house, they owned two different shoe stores. In 1885, three Hofheimer brothers, Julius Caesar, Henry Clay, and Moses, opened the Hofheimer Brother Shoe Store. The business soon grew into a regional chain. David Hirschler, a grandson of one of the founders, became president of the business in 1926, and ran it for over 40 years. In 1936, with eight locations in Virginia, Hofheimer Shoes opened a large grand store in downtown Norfolk. By 1965, they had 24 locations and David’s son Lewis Hirschler later took over the business. In 1982, Hirschler sold the chain of stores. Other longtime family-owned stores included Altschul’s Department Store. Founded in 1898 by Benjamin Altschul, it remained in business until the family sold it in the 1970s. Some Norfolk Jews were in manufacturing. David Lowenberg owned the Chesapeake and the Elizabeth Knitting Mills, which made undergarments. Lowenberg became one of the city’s most prominent business leaders, building the grand Monticello Hotel in 1899 and serving as director general of the 1907 Jamestown Exposition held in the city.

The members of both Ohef Sholom and Beth El were primarily German immigrants. By 1878, an estimated 500 Jews lived in Norfolk. Most of them were in the retail business, especially in clothing. In 1875, Jews owned 11 of the city’s 18 clothing stores. Both of Norfolk’s wholesale clothing firms, Z. and A. Hofheimer and Lowenburg, Jacobs, and Co., were Jewish owned. The Hofheimer family owned several different businesses in 1875 - in addition to the wholesale clothing house, they owned two different shoe stores. In 1885, three Hofheimer brothers, Julius Caesar, Henry Clay, and Moses, opened the Hofheimer Brother Shoe Store. The business soon grew into a regional chain. David Hirschler, a grandson of one of the founders, became president of the business in 1926, and ran it for over 40 years. In 1936, with eight locations in Virginia, Hofheimer Shoes opened a large grand store in downtown Norfolk. By 1965, they had 24 locations and David’s son Lewis Hirschler later took over the business. In 1982, Hirschler sold the chain of stores. Other longtime family-owned stores included Altschul’s Department Store. Founded in 1898 by Benjamin Altschul, it remained in business until the family sold it in the 1970s. Some Norfolk Jews were in manufacturing. David Lowenberg owned the Chesapeake and the Elizabeth Knitting Mills, which made undergarments. Lowenberg became one of the city’s most prominent business leaders, building the grand Monticello Hotel in 1899 and serving as director general of the 1907 Jamestown Exposition held in the city.

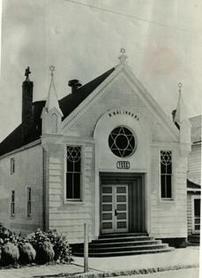

This building was the first synagogue of

This building was the first synagogue of both Ohef Sholom and Beth El.

Photo courtesy of Ohef Sholom Archives.

The Community Grows

In the late 19th century, Lowenberg‘s mills attracted a new wave of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe to settle in the area. One of Lowenberg’s mills was located just across the Elizabeth River in Berkley, which would be annexed by Norfolk in 1906. Jacob Epstein of the wholesale firm the Baltimore Bargain House, encouraged Abe Legum, an immigrant from Lithuania, to settle in Berkley and open a store catering to the mill workers in 1884. His brother Isaac soon joined him in the dry goods store. They were followed by many other Jewish immigrants, mostly from Lithuania, who also opened retail stores in Berkley. The town’s retail trade was dominated by Jewish merchants by the turn of the 20th century. The growing number of Lithuanian Jews in Berkley would gather to pray each day at Simon Salsbury’s store. In 1889, they formed Congregation Mikro Kodesh (Holy Community), which was named after a Lithuanian synagogue in Baltimore where many Berkley Jews had lived prior to coming to Virginia. Three years later, the Orthodox congregation bought land from Lowenberg and built a synagogue.

While Eastern European Jews first settled in Berkley, they soon began to populate Norfolk proper in greater numbers. By 1905, Norfolk’s Jewish community had grown to 1,200 people, and would reach 7,800 Jews by 1927. These largely immigrant newcomers created several small Orthodox congregations. B’nai Israel was founded in 1897, and had 48 members by 1900. The following year, they bought a former Methodist Church on Cumberland Avenue. As was common for the time, the real estate deed had a restrictive covenant preventing B’nai Israel from selling or renting the building to someone of African descent. Thus a congregation of Yiddish-speaking recent immigrants was afforded the benefits of whiteness in a city where the color line between black and white dominated daily life. In 1907, B’nai Israel hired Rabbi Jacob Gordon, who had been trained at a yeshiva in Lithuania. Rabbi Gordon, who gave sermons in Yiddish, led B’nai Israel for the next 40 years, serving as the unofficial rabbi for Norfolk’s entire Orthodox community.

In the late 19th century, Lowenberg‘s mills attracted a new wave of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe to settle in the area. One of Lowenberg’s mills was located just across the Elizabeth River in Berkley, which would be annexed by Norfolk in 1906. Jacob Epstein of the wholesale firm the Baltimore Bargain House, encouraged Abe Legum, an immigrant from Lithuania, to settle in Berkley and open a store catering to the mill workers in 1884. His brother Isaac soon joined him in the dry goods store. They were followed by many other Jewish immigrants, mostly from Lithuania, who also opened retail stores in Berkley. The town’s retail trade was dominated by Jewish merchants by the turn of the 20th century. The growing number of Lithuanian Jews in Berkley would gather to pray each day at Simon Salsbury’s store. In 1889, they formed Congregation Mikro Kodesh (Holy Community), which was named after a Lithuanian synagogue in Baltimore where many Berkley Jews had lived prior to coming to Virginia. Three years later, the Orthodox congregation bought land from Lowenberg and built a synagogue.

While Eastern European Jews first settled in Berkley, they soon began to populate Norfolk proper in greater numbers. By 1905, Norfolk’s Jewish community had grown to 1,200 people, and would reach 7,800 Jews by 1927. These largely immigrant newcomers created several small Orthodox congregations. B’nai Israel was founded in 1897, and had 48 members by 1900. The following year, they bought a former Methodist Church on Cumberland Avenue. As was common for the time, the real estate deed had a restrictive covenant preventing B’nai Israel from selling or renting the building to someone of African descent. Thus a congregation of Yiddish-speaking recent immigrants was afforded the benefits of whiteness in a city where the color line between black and white dominated daily life. In 1907, B’nai Israel hired Rabbi Jacob Gordon, who had been trained at a yeshiva in Lithuania. Rabbi Gordon, who gave sermons in Yiddish, led B’nai Israel for the next 40 years, serving as the unofficial rabbi for Norfolk’s entire Orthodox community.

Ohef Sholom's 1917 temple

Ohef Sholom's 1917 temple

In 1909, Orthodox Jews founded Ahavas Israel. The following year the congregation bought a building on Charlotte Street which they used as a synagogue. In 1918, another Orthodox congregation, K’hal Chasidim (Congregation of the Pious) was established. In 1928, Jews who had moved uptown created their own Orthodox congregation, the B’nai Jacob Center. The group soon acquired a former post office on 20th Street which they converted into a synagogue. In 1932, the congregation changed its name to Beth Abraham, though it was known informally as the 20th Street Shul. Rabbi Gordon of B’nai Israel helped serve these small Orthodox congregations that did not have rabbis of their own. In 1921, the city’s Orthodox community established the V’ad Hakasharos (kosher council) to oversee kosher meat in the city and to secure sacramental wine during Prohibition.

By 1929, five of the city’s seven congregations were Orthodox, though the two largest were the Reform Ohef Sholom and the Conservative Beth El. In 1900, Beth El was relatively small, with only 40 members. The congregation grew over the next decade under the rabbinic leadership of H. Benmosche and enlarged its sanctuary in 1909, doubling its seating capacity. By the early 20th century, the members of Beth El had begun to move away from strict Orthodoxy. In 1909 they hired Rabbi Louis Goldberg, who had been trained at the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary. That same year, the congregation instituted mixed-gender seating. Beth El’s religious school was especially appealing to assimilating Jewish immigrants since it offered more modern instruction than that of the Orthodox congregations and allowed girls to enroll. In 1913, Beth El became one of the 13 charter members of the United Synagogue of America, the central body of Conservative Judaism

By 1929, five of the city’s seven congregations were Orthodox, though the two largest were the Reform Ohef Sholom and the Conservative Beth El. In 1900, Beth El was relatively small, with only 40 members. The congregation grew over the next decade under the rabbinic leadership of H. Benmosche and enlarged its sanctuary in 1909, doubling its seating capacity. By the early 20th century, the members of Beth El had begun to move away from strict Orthodoxy. In 1909 they hired Rabbi Louis Goldberg, who had been trained at the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary. That same year, the congregation instituted mixed-gender seating. Beth El’s religious school was especially appealing to assimilating Jewish immigrants since it offered more modern instruction than that of the Orthodox congregations and allowed girls to enroll. In 1913, Beth El became one of the 13 charter members of the United Synagogue of America, the central body of Conservative Judaism

Final synagogue of Mikro Kodesh

Final synagogue of Mikro Kodesh

Growing Congregations

By 1921, Beth El had outgrown its building and moved to a new synagogue in the Ghent neighborhood. Rabbi Alexander Steinbach led Beth El from 1923 to 1934. He was followed by Paul Reich, who served as Beth El’s rabbi for over three decades. In 1939, Beth El added a new education building with classrooms and an auditorium. In 1950, they built a new 1400-seat sanctuary, turning the old sanctuary into a social hall; the synagogue now took up almost an entire city block. Beth El was strongly Zionist. Its female members, led by Miriam Blaustein, established Virginia’s first Hadassah chapter in 1912. Most of the leaders of Norfolk’s Zionist organizations were Beth El members. Rabbi Reich became president of the Norfolk Zionist District in 1941. Two years later, Beth El enrolled all of its members in the Zionist District.

By 1921, Beth El had outgrown its building and moved to a new synagogue in the Ghent neighborhood. Rabbi Alexander Steinbach led Beth El from 1923 to 1934. He was followed by Paul Reich, who served as Beth El’s rabbi for over three decades. In 1939, Beth El added a new education building with classrooms and an auditorium. In 1950, they built a new 1400-seat sanctuary, turning the old sanctuary into a social hall; the synagogue now took up almost an entire city block. Beth El was strongly Zionist. Its female members, led by Miriam Blaustein, established Virginia’s first Hadassah chapter in 1912. Most of the leaders of Norfolk’s Zionist organizations were Beth El members. Rabbi Reich became president of the Norfolk Zionist District in 1941. Two years later, Beth El enrolled all of its members in the Zionist District.

Rabbi Louis Mendoza.

Rabbi Louis Mendoza. Photo courtesy of Ohef Sholom Archives.

Ohef Sholom also grew significantly during the first half of the 20th century. With 120 members in 1900, the congregation soon built a new synagogue, dedicating it in 1902. Located on Freemason Street and Monticello Avenue, the two-story Italian Renaissance-style structure featured a white marble bimah and five copper domes. David Lowenburg was the major benefactor for the $70,000 building. Yet before long, the congregation grew dissatisfied with the building, especially its downtown location. Members complained about the traffic and noise from car horns that often interrupted services. In 1916, fate intervened when Ohef Sholom’s temple was destroyed by fire; luckily the Torahs were saved. The congregation met in the Ghent Club, a Jewish social organization to which many Ohef Sholom members belonged, for a year while a new temple was built. Dedicated in 1917, the new Ohef Sholom was located in the city’s Ghent neighborhood. Rabbi Edward Calisch of Beth Ahabah in Richmond, along with Norfolk’s mayor, spoke at the dedication while Christian ministers gave the opening and closing prayers.

The interfaith tone of the dedication event reflected the philosophy of Ohef Sholom’s rabbi, Louis Mendoza. Arriving in 1907, Rabbi Mendoza was known for his skills as an orator as well as his commitment to interfaith understanding. He started an annual Thanksgiving pulpit exchange with the Freemason Street Baptist Church, drawing large crowds at the church each year when he spoke. Mendoza, who led the congregation for 38 years, spoke out forcefully against the Ku Klux Klan and Henry Ford’s anti-Semitism during the 1920s. When he started a Sunday lecture program in the 1930s, he had to discontinue it after his Christian minister colleagues complained that too many of their members were choosing to attend the rabbi’s lectures rather than their services. Fittingly, the exterior of Ohef Sholom’s temple was inscribed with the quote from Isaiah: “My House Shall Be Called a House of Prayer for All Peoples.” Under Rabbi Mendoza’s leadership, Ohef Sholom grew from 90 contributing families in 1910 to over 312 by the time he retired in 1945.

The interfaith tone of the dedication event reflected the philosophy of Ohef Sholom’s rabbi, Louis Mendoza. Arriving in 1907, Rabbi Mendoza was known for his skills as an orator as well as his commitment to interfaith understanding. He started an annual Thanksgiving pulpit exchange with the Freemason Street Baptist Church, drawing large crowds at the church each year when he spoke. Mendoza, who led the congregation for 38 years, spoke out forcefully against the Ku Klux Klan and Henry Ford’s anti-Semitism during the 1920s. When he started a Sunday lecture program in the 1930s, he had to discontinue it after his Christian minister colleagues complained that too many of their members were choosing to attend the rabbi’s lectures rather than their services. Fittingly, the exterior of Ohef Sholom’s temple was inscribed with the quote from Isaiah: “My House Shall Be Called a House of Prayer for All Peoples.” Under Rabbi Mendoza’s leadership, Ohef Sholom grew from 90 contributing families in 1910 to over 312 by the time he retired in 1945.

B'nai Israel

B'nai Israel

Charitable Efforts

Members of Ohef Sholom worked to help the city’s growing number of Orthodox Jewish immigrants. In 1905, women from Ohef Sholom established a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women. By 1907, the NCJW had opened a small settlement house to help these immigrants adjust to life in America. The settlement offered classes in English and later civics; it also had a Jewish Sunday school that was unaffiliated with any congregation. In 1910, the NCJW moved the settlement house to a new building on Cumberland Street. Over time, the settlement functioned as a Jewish community center for the neighborhood, offering educational, cultural, and recreational activities. The NCJW closed the settlement house in 1939 after many Jews had moved out of the neighborhood and helping Jewish immigrants to assimilate was no longer necessary. Nevertheless, the NCJW’s Jewish Family Welfare Bureau, which had overseen the settlement house, later evolved into the Jewish Family Service.

Ohef Sholom members also established a Jewish charity hospital. The former home of Harry Lee Lowenberg was converted into Mount Sinai Hospital after a successful fundraising drive in 1921. While the hospital was open to patients of all faiths, it offered kosher food to serve the city’s large population of Orthodox Jews. The hospital had a ward for African American patients in an adjoining building. Dr. Louis Berlin was the hospital’s head physician, though both Jews and non-Jews served on its board. In 1930, it changed its name to Memorial Hospital of Norfolk. The small, 50-bed hospital was unable to survive the Great Depression and closed in 1937. A few decades later, the former hospital building became the home of Norfolk’s newly established Jewish Community Center.

Members of Ohef Sholom worked to help the city’s growing number of Orthodox Jewish immigrants. In 1905, women from Ohef Sholom established a chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women. By 1907, the NCJW had opened a small settlement house to help these immigrants adjust to life in America. The settlement offered classes in English and later civics; it also had a Jewish Sunday school that was unaffiliated with any congregation. In 1910, the NCJW moved the settlement house to a new building on Cumberland Street. Over time, the settlement functioned as a Jewish community center for the neighborhood, offering educational, cultural, and recreational activities. The NCJW closed the settlement house in 1939 after many Jews had moved out of the neighborhood and helping Jewish immigrants to assimilate was no longer necessary. Nevertheless, the NCJW’s Jewish Family Welfare Bureau, which had overseen the settlement house, later evolved into the Jewish Family Service.

Ohef Sholom members also established a Jewish charity hospital. The former home of Harry Lee Lowenberg was converted into Mount Sinai Hospital after a successful fundraising drive in 1921. While the hospital was open to patients of all faiths, it offered kosher food to serve the city’s large population of Orthodox Jews. The hospital had a ward for African American patients in an adjoining building. Dr. Louis Berlin was the hospital’s head physician, though both Jews and non-Jews served on its board. In 1930, it changed its name to Memorial Hospital of Norfolk. The small, 50-bed hospital was unable to survive the Great Depression and closed in 1937. A few decades later, the former hospital building became the home of Norfolk’s newly established Jewish Community Center.

Louis Isaac Jaffe

Louis Isaac Jaffe

Political Engagement

As the creation of the short-lived hospital shows, Jews were active in the larger Norfolk community. Norfolk Jews had a long tradition of involvement in local politics, dating back to Moses Myers in the 18th century. Michael Umstadter was elected to Norfolk’s city council in 1874, and helped establish the city’s public high school and the Norfolk public library. Several Norfolk Jews served on the city council in the early 20th century. Benjamin Banks became the first Jew elected to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1912. Banks, a lawyer who edited and published the short-lived Galaxy Magazine, was controversial. Soon after his election, his political enemies, including a local Jewish merchant, claimed that he was ineligible to serve since he was not a U.S. citizen. Banks claimed that he had been born in Baltimore, but his opponents argued that he had come to the U.S. from Russia as a small boy. Although his term in office was short, Banks was a leader of the anti-prohibition “wet” faction of Norfolk’s Democratic Party for many years. He ran unsuccessfully for Commonwealth’s Attorney in 1927. Louis Isaac Jaffe was editor of the Virginian-Pilot newspaper from 1919 to 1950. An outspoken progressive voice in Virginia, Jaffe won a Pulitzer Prize in 1929 for an anti-lynching editorial entitled “An Unspeakable Act of Savagery.”

As the creation of the short-lived hospital shows, Jews were active in the larger Norfolk community. Norfolk Jews had a long tradition of involvement in local politics, dating back to Moses Myers in the 18th century. Michael Umstadter was elected to Norfolk’s city council in 1874, and helped establish the city’s public high school and the Norfolk public library. Several Norfolk Jews served on the city council in the early 20th century. Benjamin Banks became the first Jew elected to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1912. Banks, a lawyer who edited and published the short-lived Galaxy Magazine, was controversial. Soon after his election, his political enemies, including a local Jewish merchant, claimed that he was ineligible to serve since he was not a U.S. citizen. Banks claimed that he had been born in Baltimore, but his opponents argued that he had come to the U.S. from Russia as a small boy. Although his term in office was short, Banks was a leader of the anti-prohibition “wet” faction of Norfolk’s Democratic Party for many years. He ran unsuccessfully for Commonwealth’s Attorney in 1927. Louis Isaac Jaffe was editor of the Virginian-Pilot newspaper from 1919 to 1950. An outspoken progressive voice in Virginia, Jaffe won a Pulitzer Prize in 1929 for an anti-lynching editorial entitled “An Unspeakable Act of Savagery.”

United Charitable Efforts

Although the Jewish community was divided between seven different congregations, by the mid-1930s Norfolk Jews began to unite their charitable efforts. Starting in 1936, the community held an annual United Jewish Fund campaign to raise money for local Jewish organizations and international Jewish relief. World War II helped to catalyze these efforts. The local Jewish Welfare Board worked with the USO to take care of the many Jewish soldiers stationed in the area during the war. The B’rith Shalom Center, which had been a community center for Orthodox Jews, became the JWB Club for Jewish soldiers. By 1945, Norfolk had founded the Jewish Community Council, which served as the central fundraising body as well as the public face of the community. In 1967, it changed its name to the United Jewish Federation.

Although the Jewish community was divided between seven different congregations, by the mid-1930s Norfolk Jews began to unite their charitable efforts. Starting in 1936, the community held an annual United Jewish Fund campaign to raise money for local Jewish organizations and international Jewish relief. World War II helped to catalyze these efforts. The local Jewish Welfare Board worked with the USO to take care of the many Jewish soldiers stationed in the area during the war. The B’rith Shalom Center, which had been a community center for Orthodox Jews, became the JWB Club for Jewish soldiers. By 1945, Norfolk had founded the Jewish Community Council, which served as the central fundraising body as well as the public face of the community. In 1967, it changed its name to the United Jewish Federation.

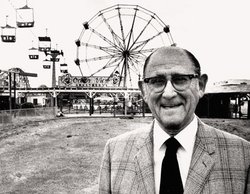

Dudley Cooper & Ocean View Amusement Park

Dudley Cooper & Ocean View Amusement Park

World War II and After

World War II helped to transform Norfolk. The Norfolk Naval Base, which had been built during World War I, was humming with activity during the war. The city’s population grew 50% between 1940 and 1942. The base would eventually become the largest naval base in the world, and the bedrock of Norfolk’s economy. By 1948, an estimated 7,500 Jews lived in Norfolk, and their numbers would continue to grow during the post-war era.

As Norfolk itself grew after the war, a handful of prominent Jews helped to reshape the city becoming some of its most powerful civic leaders. Dudley Cooper bought the dilapidated Ocean View Amusement Park in 1942. Local military officials convinced him to reopen the park so soldiers stationed in the area would have something wholesome to do in their free time. In 1946, Cooper helped open the Seaview Beach Amusement Park with three prominent African American businessmen, which became the nation’s only major amusement park for African Americans. In a 1950 newspaper article, Cooper noted that Seaview Beach was “a victory sociologically but a dud financially.” The park closed after Ocean View integrated in the 1960s. His wife Mary Cooper helped establish the Tidewater Ballet and brought one of the first exhibits of African American Art to the Chrysler Museum.

World War II helped to transform Norfolk. The Norfolk Naval Base, which had been built during World War I, was humming with activity during the war. The city’s population grew 50% between 1940 and 1942. The base would eventually become the largest naval base in the world, and the bedrock of Norfolk’s economy. By 1948, an estimated 7,500 Jews lived in Norfolk, and their numbers would continue to grow during the post-war era.

As Norfolk itself grew after the war, a handful of prominent Jews helped to reshape the city becoming some of its most powerful civic leaders. Dudley Cooper bought the dilapidated Ocean View Amusement Park in 1942. Local military officials convinced him to reopen the park so soldiers stationed in the area would have something wholesome to do in their free time. In 1946, Cooper helped open the Seaview Beach Amusement Park with three prominent African American businessmen, which became the nation’s only major amusement park for African Americans. In a 1950 newspaper article, Cooper noted that Seaview Beach was “a victory sociologically but a dud financially.” The park closed after Ocean View integrated in the 1960s. His wife Mary Cooper helped establish the Tidewater Ballet and brought one of the first exhibits of African American Art to the Chrysler Museum.

Charles Kaufman

Charles Kaufman

V.H. “Pooch” Nussbaum, Jr. took over his family’s real estate business that had been started by his grandfather Sidney Nussbaum in 1906. Nussbaum helped to revitalize Norfolk’s downtown and served on the city council from 1968 to 1974. He was vice chairman of a Citizens Advisory Committee to improve race relations in the city and worked to get open housing practices in the local real estate industry. His mother Justine Nussbaum was extremely active in local charity work. She created a fund to help those living in public housing in Norfolk and started the Needlework Guild of America, which provided new clothing for the poor. She also founded Justine’s Clothes Bank as an offshoot of a local food bank.

According to the local newspaper, Charles Kaufman and Henry Clay Hofheimer II were the “deans of the city’s power structure” in the post-war years. Kaufman, a prominent local attorney, chaired the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority from 1939 to 1966. Kaufman led the city’s urban renewal effort, tearing down slums and building new low income housing while reshaping the city’s waterfront and downtown. During the crisis over school integration in 1958, Kaufman worked behind the scenes to get the Norfolk business community to support reopening the public schools, which Governor James Almond had ordered closed to preserve segregation. Kaufman’s efforts helped turn the tide, convincing the governor to abandon massive resistance to school integration. Kaufman also helped develop Old Dominion University and Norfolk General Hospital, on whose board he served for five decades. Along with Harry Mansbach and Henry Clay Hofheimer II, Kaufman was instrumental in creating the Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk in 1973.

According to the local newspaper, Charles Kaufman and Henry Clay Hofheimer II were the “deans of the city’s power structure” in the post-war years. Kaufman, a prominent local attorney, chaired the Norfolk Redevelopment and Housing Authority from 1939 to 1966. Kaufman led the city’s urban renewal effort, tearing down slums and building new low income housing while reshaping the city’s waterfront and downtown. During the crisis over school integration in 1958, Kaufman worked behind the scenes to get the Norfolk business community to support reopening the public schools, which Governor James Almond had ordered closed to preserve segregation. Kaufman’s efforts helped turn the tide, convincing the governor to abandon massive resistance to school integration. Kaufman also helped develop Old Dominion University and Norfolk General Hospital, on whose board he served for five decades. Along with Harry Mansbach and Henry Clay Hofheimer II, Kaufman was instrumental in creating the Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk in 1973.

Henry Clay Hofheimer II.

Henry Clay Hofheimer II. Photo courtesy of Linda Kaufman.

In 1982, the Virginian-Pilot wrote, “for nearly all of his life Henry Clay Hofheimer II has worked quietly behind the scenes for practically every major community activity in Tidewater.” A year later, the newspaper called him “Norfolk’s no. 1 citizen” who had helped sparked the city’s renaissance. Hofheimer owned a concrete company in addition to several other industrial interests. He served as vice chairman of the Norfolk Planning Commission and led the Greater Norfolk Corporation, a group of over 40 business leaders who organized to promote economic development and downtown renewal in the city. He served as chairman of Norfolk General Hospital as well as the Chrysler Museum of Art. Hofheimer raised money for several civic improvement projects. As president of the Eastern Virginia Medical Foundation, Hofheimer led the effort to raise $15 million to create Norfolk’s medical school. As a board member of Virginia Wesleyan College, he led the effort to raise money for a new library, which was named after him. A new building at the medical school was also named in Hofheimer’s honor.

Norfolk looks the way it does today largely because of Kaufman and Hofheimer. Close friends, they even became in-laws when Kaufman’s son George married Hofheimer’s daughter Linda. A prominent real estate developer, George Kaufman started the Guest Quarters hotel chain while he and Linda became major philanthropists and amassed a large collection of early American furniture.

Norfolk looks the way it does today largely because of Kaufman and Hofheimer. Close friends, they even became in-laws when Kaufman’s son George married Hofheimer’s daughter Linda. A prominent real estate developer, George Kaufman started the Guest Quarters hotel chain while he and Linda became major philanthropists and amassed a large collection of early American furniture.

Temple Israel.

Temple Israel. Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

Congregations in the Second Half of the 20th Century

In the years after World War II, a growing number of Norfolk Jews were moving out to the new suburban Wards Corner neighborhood. In 1952, a large group of them met to discuss forming a new congregation in Wards Corner. Naming themselves Temple Israel, the group had 181 families join the new congregation right away. Only a week after the founding meeting, Temple Israel held its first services at Benmorrell Chapel with Rabbi Murray Kantor of Suffolk’s Agudath Achim congregation leading them. The congregation, which joined the Conservative movement early on, developed quickly. In 1953 they hired Rabbi Joseph Goldman, who stayed at Temple Israel for 30 years. The following year, with 450 members, they bought land and laid the cornerstone for their first synagogue. Since they were growing so fast, their synagogue was built in two phases: a multi-purpose auditorium was dedicated in 1956, while the sanctuary was completed in 1960. Temple Israel thrived as Wards Corner became the geographic center of Norfolk’s Jewish population. In 1974, 35% of Norfolk’s Jews lived in the neighborhood. Rabbi Michael Panitz began serving the congregation in 1992.

In the years after World War II, a growing number of Norfolk Jews were moving out to the new suburban Wards Corner neighborhood. In 1952, a large group of them met to discuss forming a new congregation in Wards Corner. Naming themselves Temple Israel, the group had 181 families join the new congregation right away. Only a week after the founding meeting, Temple Israel held its first services at Benmorrell Chapel with Rabbi Murray Kantor of Suffolk’s Agudath Achim congregation leading them. The congregation, which joined the Conservative movement early on, developed quickly. In 1953 they hired Rabbi Joseph Goldman, who stayed at Temple Israel for 30 years. The following year, with 450 members, they bought land and laid the cornerstone for their first synagogue. Since they were growing so fast, their synagogue was built in two phases: a multi-purpose auditorium was dedicated in 1956, while the sanctuary was completed in 1960. Temple Israel thrived as Wards Corner became the geographic center of Norfolk’s Jewish population. In 1974, 35% of Norfolk’s Jews lived in the neighborhood. Rabbi Michael Panitz began serving the congregation in 1992.

B'nai Israel

B'nai Israel

While Conservative Judaism expanded in the post-war years, Norfolk’s Orthodox congregations consolidated as they struggled to keep up with their members who were moving out to the suburbs. In 1946, K’hal Chasidim and Beth Abraham merged to form the United Orthodox Synagogue. In 1951, Ahavas Israel joined with B’nai Israel, a merger encouraged by Rabbi Reich of Temple Beth El who wanted Norfolk’s shrinking Orthodox groups to form one strong congregation. By the end of the decade, Rabbi Reich got his wish. In 1952, Orthodox Jews who had moved to Wards Corner established their own congregation, while B’nai Israel was struggling due to so many of its members moving away from downtown. B’nai Israel decided to merge with the new group, which kept the name B’nai Israel. Finally, in 1958, the United Orthodox Synagogue joined with B’nai Israel, marking the complete consolidation of Orthodox congregations in Norfolk. Rabbi Joseph Schechter of UOS led the new combined congregation.

By this time, Mikro Kodesh in Berkley had become inactive as most of the Jews who lived in the neighborhood had moved to other parts of Norfolk and beyond. In the early 1960s, the remaining members sold their synagogue, giving their ark to Rodef Sholom in Hampton and their memorial boards to an Orthodox seminary in Maryland. Despite these mergers, Norfolk’s Orthodox community remained strong. Starting in 1947, the Jewish Community Council helped to supervise the production of kosher meat, while in 1954 Orthodox Jews built a community mikvah. In 2013, B’nai Israel numbered 225 families while the Orthodox community supported a yeshiva for high school boys as well as a high school for girls.

Ohef Sholom remained the city’s only Reform congregation and thrived during the post-war era. Rabbi Malcolm Stern led the congregation from 1947 to 1964; he brought back the bar mitzvah ritual which had been dropped during Rabbi Mendoza’s tenure. Rabbi Stern led the congregation’s first interracial service during Brotherhood Week in 1952. The congregation expanded its synagogue to keep up with its growth, adding a new social hall, kitchen, and classrooms in 1951. In 1965, they built another addition, which they named after Rabbi Mendoza, as their membership had grown to over 450 families at the time. Lawrence Forman became the congregation’s senior rabbi in 1970, leading Ohef Sholom until his retirement in 2000. During his tenure, the congregation grew to 735 families in 1995. Minette Cooper became Ohef Sholom’s first female president in 1985.

By this time, Mikro Kodesh in Berkley had become inactive as most of the Jews who lived in the neighborhood had moved to other parts of Norfolk and beyond. In the early 1960s, the remaining members sold their synagogue, giving their ark to Rodef Sholom in Hampton and their memorial boards to an Orthodox seminary in Maryland. Despite these mergers, Norfolk’s Orthodox community remained strong. Starting in 1947, the Jewish Community Council helped to supervise the production of kosher meat, while in 1954 Orthodox Jews built a community mikvah. In 2013, B’nai Israel numbered 225 families while the Orthodox community supported a yeshiva for high school boys as well as a high school for girls.

Ohef Sholom remained the city’s only Reform congregation and thrived during the post-war era. Rabbi Malcolm Stern led the congregation from 1947 to 1964; he brought back the bar mitzvah ritual which had been dropped during Rabbi Mendoza’s tenure. Rabbi Stern led the congregation’s first interracial service during Brotherhood Week in 1952. The congregation expanded its synagogue to keep up with its growth, adding a new social hall, kitchen, and classrooms in 1951. In 1965, they built another addition, which they named after Rabbi Mendoza, as their membership had grown to over 450 families at the time. Lawrence Forman became the congregation’s senior rabbi in 1970, leading Ohef Sholom until his retirement in 2000. During his tenure, the congregation grew to 735 families in 1995. Minette Cooper became Ohef Sholom’s first female president in 1985.

The Jewish Community in Norfolk Today

Beth El Temple

Beth El Temple

While the process of suburbanization began with Norfolk Jews moving to areas like Wards Corner, in recent decades it has drawn many of them to other cities, especially Virginia Beach. A 1974 study found that over twice as many Jewish households lived in Norfolk than in Virginia Beach. During the 1980s, more and more Jews from throughout Hampton Roads moved to Virginia Beach. By the 1990s, more Jews lived in Virginia Beach than in Norfolk. By 2001, Virginia Beach’s Jewish population was almost twice as large as Norfolk’s. This decline has not had a significant impact on Norfolk’s congregations since most Jews who have left the city have maintained their membership in their old synagogues. Today, over half of Temple Beth El’s 650 families live in Virginia Beach. In 2000, Temple Israel formed a partnership with the new Kehillat Bet Hamidrash congregation in the Kempsville section of Virginia Beach to do joint programming to better reach its members who had moved to the area.

Sanctuary of Ohef Sholom

Sanctuary of Ohef Sholom

This shift toward Virginia Beach was solidified in 2004 with the establishment of a centralized Tidewater Jewish campus in Virginia Beach. Though it is located close to the Norfolk border, the Virginia Beach campus is now home to several Jewish communal organizations that had once been located in Norfolk, including the Jewish Federation, the Hebrew Academy Day School, the Jewish Family Service, and the Jewish Community Center. While Norfolk may no longer be the center of the Tidewater’s Jewish community, it remains the religious home and historic cradle of Jewish life in Hampton Roads.