Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg: Historical Overview

Petersburg, Virginia, was founded in 1635 by English colonists who recognized its potential as an economic hub. Situated on the Appomattox River just 23 miles south of Richmond, Petersburg became a thriving industrial city and transportation center, evolving to accommodate the transfer of goods travelling by ship, railroad, and later, by trucks. During the Civil War, Petersburg became the transportation lifeline of the Confederate capital Richmond—and just days after Petersburg fell to Union troops, the entire Confederacy had to surrender.

Jews have lived in Petersburg since the 18th century, and a small Jewish community remains today.

Jews have lived in Petersburg since the 18th century, and a small Jewish community remains today.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Petersburg

Samuel Mordecai

Samuel Mordecai

Early Settlers

In 1789, Samuel Myers arrived as the first Jewish resident of Petersburg. Traveling from Norfolk, Myers came to Petersburg to open Samuel Myers and Brothers, a tobacco firm he started with his brothers, Moses and Sampson. Samuel quickly became a well-known merchant in town, establishing himself as the first in a long family line of successful businessmen in Petersburg. Just two years later, Hyman Samuel, a watch and clockmaker, arrived in Petersburg from London.

In the decades following Myers and Samuel’s settlement, Petersburg continued to welcome Jewish merchants to the growing city, most of whom shared a common German origin. By the 1820s, largely due to its location on the Appomattox River with easy access to both Richmond and Norfolk, Petersburg had become a bustling port city and manufacturing center for exporting cheap goods across the Atlantic. Jews were central to this economic activity as both overseas traders and retailers of dry good in the city.

For the most part, Petersburg Jews were very well-respected by the larger Christian community. One such figure was A.S. Naustedler, who arrived in Petersburg in 1823 from Ausburg, Germany. While there was no formal congregation in Petersburg at the time, Nastedler was said to officiate at occasional religious meetings with his brethren, and was even called ‘rabbi’ by his friends and acquaintances. Outside of the small Jewish community, Naustedler—or ‘Old Naus,’ as he was called—also earned a reputation for his friendly debates with an Irishman in town named O’Hara. In fact, for many years afterward, a silhouette of Naustedler and O’Hara engaged in a playful argument over a cup of tea was hung at Southerland’s, a local grocery store.

In 1789, Samuel Myers arrived as the first Jewish resident of Petersburg. Traveling from Norfolk, Myers came to Petersburg to open Samuel Myers and Brothers, a tobacco firm he started with his brothers, Moses and Sampson. Samuel quickly became a well-known merchant in town, establishing himself as the first in a long family line of successful businessmen in Petersburg. Just two years later, Hyman Samuel, a watch and clockmaker, arrived in Petersburg from London.

In the decades following Myers and Samuel’s settlement, Petersburg continued to welcome Jewish merchants to the growing city, most of whom shared a common German origin. By the 1820s, largely due to its location on the Appomattox River with easy access to both Richmond and Norfolk, Petersburg had become a bustling port city and manufacturing center for exporting cheap goods across the Atlantic. Jews were central to this economic activity as both overseas traders and retailers of dry good in the city.

For the most part, Petersburg Jews were very well-respected by the larger Christian community. One such figure was A.S. Naustedler, who arrived in Petersburg in 1823 from Ausburg, Germany. While there was no formal congregation in Petersburg at the time, Nastedler was said to officiate at occasional religious meetings with his brethren, and was even called ‘rabbi’ by his friends and acquaintances. Outside of the small Jewish community, Naustedler—or ‘Old Naus,’ as he was called—also earned a reputation for his friendly debates with an Irishman in town named O’Hara. In fact, for many years afterward, a silhouette of Naustedler and O’Hara engaged in a playful argument over a cup of tea was hung at Southerland’s, a local grocery store.

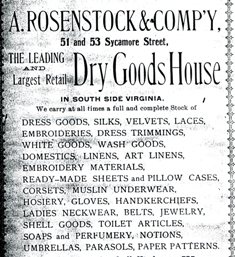

Ad from 1908

Ad from 1908

Another prominent German Jewish family in Petersburg at the time was that of Jacob Mordecai, who moved to Petersburg from Richmond, where he had been one of the founders of Beth Shalome Congregation in 1791. His family moved to Petersburg the following year, where Jacob’s brother-in-law Samuel Myers had established himself. Once in Petersburg, Jacob’s oldest son Moses began to practice law, and his son Samuel became a successful merchant of cloth and tobacco. By 1830, Samuel Mordecai had become the director of the newly organized Petersburg Railroad Company—which would soon become a crucial part of the city landscape—and by 1832 he was listed as the director of Merchants Manufacturing Company, a large cotton manufacturer employing about 200 people. Samuel was not as religiously devout as most of his Christians neighbors. Commenting amusingly on the atmosphere of spiritual fervor in Petersburg, Mordecai wrote to his sister Ellen in 1822: “A Doctor of Divinity would thrive better here than an M.D. for half the town is heavenly mad.” Though not religious himself, Samuel was certainly knowledgeable about Judaism—most likely due to his father’s piety—and sometimes wrote to remind his siblings of the dates of the Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, and Sukkot. Still, there is no record indicating that Samuel or his siblings ever joined together to worship on such holidays in Petersburg.

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, Petersburg continued to grow as an important industrial and transportation center, becoming the second-biggest city in Virginia, after Richmond. The Petersburg Railroad contained lines to Richmond, Farmville, Lynchburg, and North Carolina, making Petersburg a major transfer point for both north-south and east-west travel. This, along with the growth of tobacco manufacturing, flour mills, and the cotton businesses, attracted Jewish immigrants, mostly from Germany and England, to settle as merchants in Petersburg. By 1859, the Petersburg City Directory listed 49 Jewish households and 27 businesses owned by Jews: 17 dry goods stores, four fancy and variety stores, four millinery stores, one leather and hides business, and one bottling works. One of these dry good stores, owned by 26-year-old Anthony Rosenstock, would become the most important department store in the city for the next 100 years. Rosenstock, who later became a prominent member of the Jewish congregation, somewhat ostentatiously advertised his store as the “Temple of Fancy.”

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, Petersburg continued to grow as an important industrial and transportation center, becoming the second-biggest city in Virginia, after Richmond. The Petersburg Railroad contained lines to Richmond, Farmville, Lynchburg, and North Carolina, making Petersburg a major transfer point for both north-south and east-west travel. This, along with the growth of tobacco manufacturing, flour mills, and the cotton businesses, attracted Jewish immigrants, mostly from Germany and England, to settle as merchants in Petersburg. By 1859, the Petersburg City Directory listed 49 Jewish households and 27 businesses owned by Jews: 17 dry goods stores, four fancy and variety stores, four millinery stores, one leather and hides business, and one bottling works. One of these dry good stores, owned by 26-year-old Anthony Rosenstock, would become the most important department store in the city for the next 100 years. Rosenstock, who later became a prominent member of the Jewish congregation, somewhat ostentatiously advertised his store as the “Temple of Fancy.”

Marker for Rodof Sholom cemetery, established in 1865.

Marker for Rodof Sholom cemetery, established in 1865.

Organized Jewish Life in Petersburg

This rising Jewish presence in Petersburg culminated on August 15, 1858, when Congregation Rodof Sholom (“Pursuer of Peace”) was organized. Congregants initially gathered in a building on Sycamore Street, with future plans to build a synagogue. Sigmund Hutzler, who emigrated from Bavaria and ran a bottling plant in Petersburg, was the first president of the group. In January 1859, the newly formed Hebrew Benevolent Society of Petersburg threw a ball to raise funds for the congregation, and a few days later Hutzler announced that they were making progress on the completion of the synagogue building. Around the same time, the congregation brought its first chazzan, Mr. Gabrielle, to Petersburg from New York to help establish a Hebrew school. By spring of 1859, Rodof Sholom appeared to be thriving. When Rabbi Isaac Leeser, the editor of the Occident, visited Petersburg in May, he reported that there was an air of prosperity among the Jewish community, and applauded the presence of a benevolent aid society for Jewish travelers passing through town.

However, progress of the nascent congregation slowed soon after. In March 1860, Leeser received a letter from a Petersburg resident about the sad state of the congregation, citing the continued lack of a synagogue building and cemetery, in addition to the dissolution of the Hebrew Benevolent Society. Historian Louis Ginsberg speculates that differences in religious observance may have contributed to the congregation’s plight. An article in the Petersburg Daily Express reported that some members of the congregation recently “have determined to observe Jewish Sabbath,” so many of their stores would be closed on Saturdays. This new instance of religiosity within the Reform-leaning Jewish community, Ginsberg suspects, could have caused a split in the congregation and slowed its development.

Additionally, the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 undoubtedly hindered the congregation’s progress. Because of the city’s position as a railroad center, Petersburg was a key strategic city for both armies. Though most of the Jews in Petersburg were newly arrived immigrants, nearly all of them supported the Confederate cause, and many fought for the Confederate Army. Sigmund Hutzler, the first president of Rodof Sholom, served in the Virginia infantry. Despite the turmoil of the war years, the congregation was able to purchase land for a cemetery in 1864.

After the war, as business and social life resumed, so too did the Jewish community’s religious activity. In 1865, an article in the American Israelite mentioned Rodof Sholom’s desire to hire a rabbi, and in 1866, Rev. M.J. Oppenheimer answered the call. Oppenheimer served the congregation’s 35 members for four years, leading services in the basement of the Masonic Hall on Tabb Street and teaching classes in both Hebrew and German on Sunday afternoons. During subsequent years, the congregants worked hard to raise the funds for a synagogue, throwing benefit balls and community fairs. In May 1875, Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise spoke passionately to the congregation about Reform Judaism—and just a week later, Rodof Sholom officially joined Wise’s Union of Hebrew Congregations.

Not all members Petersburg’s Jewish community were happy with this decision. In 1871, one had published an editorial in the Petersburg Daily Courier arguing that any attempt to reform traditional practices “was at the outset in direct opposition to Jewish tradition.” Controversy later arose in the congregation regarding the wearing of hats. When one member of Rodof Sholom stood up to advocate the uncovering of heads at a congregation meeting, a spirited debate ensued. According to an unsigned letter published in the American Israelite, some argued that “style demanded it,” while another agreed “simply because he thought [hats] looked bad.” Yet another member reasoned that “all religious pictures of our ancestors showed them with their hats off,” thus it was not a binding principle of Judaism. In response, another man “spoke very bitterly against the measure, basing his position upon Jewish Law.” Ultimately, after a heated debate, the motion was tabled for later discussion.

After 18 years of fundraising and planning, Rodof Sholom finally laid the cornerstone for its synagogue on Union Street on July 14, 1876. Rabbi Alexander Gross presided over this major public event, which included a processional through downtown, a brass band, and representatives of all of Petersburg’s Masonic Lodges. The city’s mayor, William E. Cameron, delivered an address, as did Isaac Mayer Wise, who returned for the event. According to the Jewish Messenger the celebration consisted of a “large assemblage—both Jews and Gentiles…[the] Mayor of the City spoke at some length, and hoped that this day begins a long future of plenty, peace and happiness to the Israelites of Petersburg.” Services at the new synagogue were equally lively, complete with a “melodeon” and a voluntary choir “consisting of a quartette, the first soprano a Christian lady,” according to the American Israelite. Despite the use of an organ and choir, the article went on to note that the service was “not exactly in the reform style.” At the time, the congregation had between 20 and 30 members, as well as 34 pupils in its newly organized Sunday School. An estimated 163 Jews lived in Petersburg in 1876.

In addition to the synagogue, Petersburg Jews launched other organizations, including B’nai B’rith headed by Anthony Rosenstock, the Hebrew Ladies’ Benevolent Society led by his wife Celia Rosenstock, and even a Hebrew Dramatic Association. By 1882, Rodof Sholom’s newly elected Rabbi Louis Nusbaum first established the Young Men’s Hebrew Association in a building on Sycamore Street. Jews also helped organize clubs outside of their religious community; the German Club of Petersburg, for instance, was also headed by two Jews, A.S. Reinach and J. Rosenfeld.

This rising Jewish presence in Petersburg culminated on August 15, 1858, when Congregation Rodof Sholom (“Pursuer of Peace”) was organized. Congregants initially gathered in a building on Sycamore Street, with future plans to build a synagogue. Sigmund Hutzler, who emigrated from Bavaria and ran a bottling plant in Petersburg, was the first president of the group. In January 1859, the newly formed Hebrew Benevolent Society of Petersburg threw a ball to raise funds for the congregation, and a few days later Hutzler announced that they were making progress on the completion of the synagogue building. Around the same time, the congregation brought its first chazzan, Mr. Gabrielle, to Petersburg from New York to help establish a Hebrew school. By spring of 1859, Rodof Sholom appeared to be thriving. When Rabbi Isaac Leeser, the editor of the Occident, visited Petersburg in May, he reported that there was an air of prosperity among the Jewish community, and applauded the presence of a benevolent aid society for Jewish travelers passing through town.

However, progress of the nascent congregation slowed soon after. In March 1860, Leeser received a letter from a Petersburg resident about the sad state of the congregation, citing the continued lack of a synagogue building and cemetery, in addition to the dissolution of the Hebrew Benevolent Society. Historian Louis Ginsberg speculates that differences in religious observance may have contributed to the congregation’s plight. An article in the Petersburg Daily Express reported that some members of the congregation recently “have determined to observe Jewish Sabbath,” so many of their stores would be closed on Saturdays. This new instance of religiosity within the Reform-leaning Jewish community, Ginsberg suspects, could have caused a split in the congregation and slowed its development.

Additionally, the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 undoubtedly hindered the congregation’s progress. Because of the city’s position as a railroad center, Petersburg was a key strategic city for both armies. Though most of the Jews in Petersburg were newly arrived immigrants, nearly all of them supported the Confederate cause, and many fought for the Confederate Army. Sigmund Hutzler, the first president of Rodof Sholom, served in the Virginia infantry. Despite the turmoil of the war years, the congregation was able to purchase land for a cemetery in 1864.

After the war, as business and social life resumed, so too did the Jewish community’s religious activity. In 1865, an article in the American Israelite mentioned Rodof Sholom’s desire to hire a rabbi, and in 1866, Rev. M.J. Oppenheimer answered the call. Oppenheimer served the congregation’s 35 members for four years, leading services in the basement of the Masonic Hall on Tabb Street and teaching classes in both Hebrew and German on Sunday afternoons. During subsequent years, the congregants worked hard to raise the funds for a synagogue, throwing benefit balls and community fairs. In May 1875, Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise spoke passionately to the congregation about Reform Judaism—and just a week later, Rodof Sholom officially joined Wise’s Union of Hebrew Congregations.

Not all members Petersburg’s Jewish community were happy with this decision. In 1871, one had published an editorial in the Petersburg Daily Courier arguing that any attempt to reform traditional practices “was at the outset in direct opposition to Jewish tradition.” Controversy later arose in the congregation regarding the wearing of hats. When one member of Rodof Sholom stood up to advocate the uncovering of heads at a congregation meeting, a spirited debate ensued. According to an unsigned letter published in the American Israelite, some argued that “style demanded it,” while another agreed “simply because he thought [hats] looked bad.” Yet another member reasoned that “all religious pictures of our ancestors showed them with their hats off,” thus it was not a binding principle of Judaism. In response, another man “spoke very bitterly against the measure, basing his position upon Jewish Law.” Ultimately, after a heated debate, the motion was tabled for later discussion.

After 18 years of fundraising and planning, Rodof Sholom finally laid the cornerstone for its synagogue on Union Street on July 14, 1876. Rabbi Alexander Gross presided over this major public event, which included a processional through downtown, a brass band, and representatives of all of Petersburg’s Masonic Lodges. The city’s mayor, William E. Cameron, delivered an address, as did Isaac Mayer Wise, who returned for the event. According to the Jewish Messenger the celebration consisted of a “large assemblage—both Jews and Gentiles…[the] Mayor of the City spoke at some length, and hoped that this day begins a long future of plenty, peace and happiness to the Israelites of Petersburg.” Services at the new synagogue were equally lively, complete with a “melodeon” and a voluntary choir “consisting of a quartette, the first soprano a Christian lady,” according to the American Israelite. Despite the use of an organ and choir, the article went on to note that the service was “not exactly in the reform style.” At the time, the congregation had between 20 and 30 members, as well as 34 pupils in its newly organized Sunday School. An estimated 163 Jews lived in Petersburg in 1876.

In addition to the synagogue, Petersburg Jews launched other organizations, including B’nai B’rith headed by Anthony Rosenstock, the Hebrew Ladies’ Benevolent Society led by his wife Celia Rosenstock, and even a Hebrew Dramatic Association. By 1882, Rodof Sholom’s newly elected Rabbi Louis Nusbaum first established the Young Men’s Hebrew Association in a building on Sycamore Street. Jews also helped organize clubs outside of their religious community; the German Club of Petersburg, for instance, was also headed by two Jews, A.S. Reinach and J. Rosenfeld.

Civic Involvement

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, Petersburg Jews were very involved in local government. A.S. Reinach was a member of city council, George Davis was councilman for the Second Ward, Jacob Peyser was Justice of the Peace in the First Ward, and Godfrey May was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates. Jews were also leaders of the local business community. In 1886, E.T.D. Myers was president of the Petersburg Railroad Company, while Myer Saal was president of the Commercial Club. This tradition of civic involvement has continued into the 21st century. Norman Sisisky represented Virginia’s 4th District in Congress from 1983 until his death in 2001.

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, Petersburg Jews were very involved in local government. A.S. Reinach was a member of city council, George Davis was councilman for the Second Ward, Jacob Peyser was Justice of the Peace in the First Ward, and Godfrey May was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates. Jews were also leaders of the local business community. In 1886, E.T.D. Myers was president of the Petersburg Railroad Company, while Myer Saal was president of the Commercial Club. This tradition of civic involvement has continued into the 21st century. Norman Sisisky represented Virginia’s 4th District in Congress from 1983 until his death in 2001.

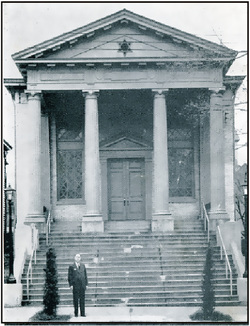

Brith Achim's first synagogue

Brith Achim's first synagogue

New Arrivals

In the late 19th century, Petersburg’s Jewish population saw some significant shifts. A number of Jewish immigrants—many of whom had fled pogroms in Russia and Poland and sought refuge in the US—ended up with relatives in Petersburg. This new group of Jews practiced in a more traditional fashion than did the earlier wave of Reform-oriented German immigrants. Soon after they arrived, they organized their own Orthodox minyan that worshiped above Jack Levenson’s dry good store on Sycamore Street. During the High Holidays, the group held services in the old Library Hall, using a sheet to separate men from women.

Soon after the turn of the 20th century, this group began to organize itself more formally as Congregation Brith Achim (Covenant of Brothers). In 1905, they purchased land from the established Rodof Sholom Synagogue for their own cemetery, and in February 1908, the congregation formally adopted its constitution, which included provisions for hiring a chazzan (service leader) and shochet (kosherbutcher), but not a rabbi. The Rev. Louis Cantor, who had arrived in Petersburg three years earlier, quickly filled this position as the first chazzan/shochet and also helped found the Chevre Kadisha (burial society). Furniture store owner Jacob Smith, who arrived in Petersburg in 1890 from Poland, became the first president of the congregation. At the time of its official founding in 1908, Brith Achim had 37 members, representing only 19 distinct families. Because so many Jewish immigrants followed relatives to Petersburg to partner in business, the new congregation consisted of a handful of extended family networks. In 1915, the congregation constructed its first synagogue on North Market Street.

Though only men were counted in Brith Achim’s minyan, women, too, contributed a great deal to the new congregation. In 1912, Katie Friedenberg organized the first Sunday School, which was held in the YMHA building. In 1918, Hannah Alperin Cooper organized the Ladies Auxiliary of Brith Achim—later renamed the Sisterhood—and became its first president. This group helped to maintain the Sunday School.

In the late 19th century, Petersburg’s Jewish population saw some significant shifts. A number of Jewish immigrants—many of whom had fled pogroms in Russia and Poland and sought refuge in the US—ended up with relatives in Petersburg. This new group of Jews practiced in a more traditional fashion than did the earlier wave of Reform-oriented German immigrants. Soon after they arrived, they organized their own Orthodox minyan that worshiped above Jack Levenson’s dry good store on Sycamore Street. During the High Holidays, the group held services in the old Library Hall, using a sheet to separate men from women.

Soon after the turn of the 20th century, this group began to organize itself more formally as Congregation Brith Achim (Covenant of Brothers). In 1905, they purchased land from the established Rodof Sholom Synagogue for their own cemetery, and in February 1908, the congregation formally adopted its constitution, which included provisions for hiring a chazzan (service leader) and shochet (kosherbutcher), but not a rabbi. The Rev. Louis Cantor, who had arrived in Petersburg three years earlier, quickly filled this position as the first chazzan/shochet and also helped found the Chevre Kadisha (burial society). Furniture store owner Jacob Smith, who arrived in Petersburg in 1890 from Poland, became the first president of the congregation. At the time of its official founding in 1908, Brith Achim had 37 members, representing only 19 distinct families. Because so many Jewish immigrants followed relatives to Petersburg to partner in business, the new congregation consisted of a handful of extended family networks. In 1915, the congregation constructed its first synagogue on North Market Street.

Though only men were counted in Brith Achim’s minyan, women, too, contributed a great deal to the new congregation. In 1912, Katie Friedenberg organized the first Sunday School, which was held in the YMHA building. In 1918, Hannah Alperin Cooper organized the Ladies Auxiliary of Brith Achim—later renamed the Sisterhood—and became its first president. This group helped to maintain the Sunday School.

Brith Achim's co-ed choir and organ

Brith Achim's co-ed choir and organ reflected its movement away from Orthodox Judaism.

With the Jewish population in Petersburg growing, there was little competition between the newer, more Orthodox Brith Achim and the older, Reform Rodof Sholom. In fact, whenever Brith Achim struggled to make a minyan on its own, members of Rodof Sholom would send over a few members to help out. However, by the late 1920s, the overall Jewish population in Petersburg began to wane as commercial activity in the city slowed during the Great Depression. According to the American Jewish Year Book, Petersburg’s Jewish population dropped from 705 to 393 between 1927 and 1937. As a result, the two congregations could no longer afford to be so congenial. Rather, they often found themselves in competition for membership.

Brith Achim, for instance, made a conscious effort to modernize and attract young Jews to their congregation by shifting its services and Hebrew School to a more Conservative, modern style. According to the 1927 board meeting minutes, such changes would aid in “keeping [congregants] from drifting away altogether to competitive synagogues and temples”—namely, Rodof Sholom. To affirm this shift away from traditional Judaism, Brith Achim hired Rabbi Joseph E. Raffaeli in 1928, who maintained two different Shabbat services: one Orthodox in Hebrew and Yiddish; and one Conservative in English with occasional Yiddish. After Raffaeli left in 1931, many of the subsequent rabbis were graduates of the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, a major institution of Conservative Judaism. From 1937 to 1943, Brith Achim even employed Rabbi Joseph Utschen, a graduate of the Reform seminary Hebrew Union College, further reflecting the congregation’s shift away from Orthodoxy.

Brith Achim, for instance, made a conscious effort to modernize and attract young Jews to their congregation by shifting its services and Hebrew School to a more Conservative, modern style. According to the 1927 board meeting minutes, such changes would aid in “keeping [congregants] from drifting away altogether to competitive synagogues and temples”—namely, Rodof Sholom. To affirm this shift away from traditional Judaism, Brith Achim hired Rabbi Joseph E. Raffaeli in 1928, who maintained two different Shabbat services: one Orthodox in Hebrew and Yiddish; and one Conservative in English with occasional Yiddish. After Raffaeli left in 1931, many of the subsequent rabbis were graduates of the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, a major institution of Conservative Judaism. From 1937 to 1943, Brith Achim even employed Rabbi Joseph Utschen, a graduate of the Reform seminary Hebrew Union College, further reflecting the congregation’s shift away from Orthodoxy.

Rabbi Alexander Goode.

Rabbi Alexander Goode.

World War II

In the wake of World War II, Jews from both congregations organized to raise funds for Jewish communities worldwide, including the Joint Distribution Fund to aid refugees from Nazism, the Petersburg Chapter of Hadassah, a women’s Zionist organization that addressed health and education in Israel, the Petersburg section of the National Council of Jewish Women, and the United Jewish Community Fund of Petersburg. These organizations received a generous response from the non-Jewish community of Petersburg as well, which at one point contributed $6,000 to the relief cause. During World War II, 77 Jewish residents of Petersburg served in the armed forces. One of the most well-known Jewish heroes of the war, Rabbi Alexander Goode, spent three years in Petersburg as a teenager when his father served as Rodof Sholom’s rabbi from 1923 to 1926. Rabbi Goode was one of the U.S. Army’s “four chaplains,” who sacrificed their own lives to save others during the sinking of the Dorchester, helping soldiers board the lifeboats and giving away their own life jackets.

In the wake of World War II, Jews from both congregations organized to raise funds for Jewish communities worldwide, including the Joint Distribution Fund to aid refugees from Nazism, the Petersburg Chapter of Hadassah, a women’s Zionist organization that addressed health and education in Israel, the Petersburg section of the National Council of Jewish Women, and the United Jewish Community Fund of Petersburg. These organizations received a generous response from the non-Jewish community of Petersburg as well, which at one point contributed $6,000 to the relief cause. During World War II, 77 Jewish residents of Petersburg served in the armed forces. One of the most well-known Jewish heroes of the war, Rabbi Alexander Goode, spent three years in Petersburg as a teenager when his father served as Rodof Sholom’s rabbi from 1923 to 1926. Rabbi Goode was one of the U.S. Army’s “four chaplains,” who sacrificed their own lives to save others during the sinking of the Dorchester, helping soldiers board the lifeboats and giving away their own life jackets.

Brith Achim's 1955 synagogue

Brith Achim's 1955 synagogue

The Post-War Years

In the decades following World War II, as industry flourished across the country and Richmond came to dominate the region economically, Petersburg’s development slowed. The city’s population plateaued at around 35,000 residents, while the Jewish community increased slightly to 600 people by 1960, but then ceased to grow. Temple Rodof Sholom moved to a new building in 1949, but could not afford to hire a full-time rabbi because of financial constraints. Instead, the congregation routinely brought in visiting Rabbi Ariel Goldberg from Richmond’s Beth Ahaba congregation to conduct services. In 1962, Rodof Sholom had to stop bringing in Rabbi Goldberg due to their difficult financial situation. By 1950, Congregation Brith Achim formally aligned with the Conservative movement, joining the United Synagogue. Five years later, they moved to a new building on South Boulevard, where the synagogue currently stands. Virginia Governor Thomas Stanley spoke at the formal dedication, while Rabbi Solomon Jacobson, who served the congregation from 1951-1973, presided over the ceremony.

Throughout the 1950s, both congregations continued to face demographic pressures. In 1954, Rodof Sholom, with only 16 contributing members, reached out to Brith Achim regarding the possibility of a merger, citing their desire to preserve what remained of the Jewish community in Petersburg. While the president of Brith Achim, Dr. Julius H. Hopkins, reacted positively to the idea, not all of his congregants did. In a letter to the secretary of Rodof Sholom, Hopkins agreed that there was no longer a need for two separate congregations and that “a combined temple would soon lead to one of the strongest and most exemplary of Southern Jewish communities of our size.” However, after only one month of the trial period that was supposed to last six, Brith Achim officers realized that some of their members were unhappy with the new arrangement. In particular, they disliked the services, which included use of the Reform Union Prayer Book, organ music, optional skull caps, and English liturgy. When several members stopped attending services, Brith Achim decided to terminate the trial merger. Seven years later, in 1961, tensions arose again between the two congregations when Rabbi Ariel Goldberg sent out an invitation to Brith Achim’s congregants to attend the services he was leading at Rodeph Sholom. Brith Achim’s board wrote to their members that such an invitation was “a highly unethical and improper practice and as a trespass upon and disrespect to our own congregation and Rabbi.”

In the decades following World War II, as industry flourished across the country and Richmond came to dominate the region economically, Petersburg’s development slowed. The city’s population plateaued at around 35,000 residents, while the Jewish community increased slightly to 600 people by 1960, but then ceased to grow. Temple Rodof Sholom moved to a new building in 1949, but could not afford to hire a full-time rabbi because of financial constraints. Instead, the congregation routinely brought in visiting Rabbi Ariel Goldberg from Richmond’s Beth Ahaba congregation to conduct services. In 1962, Rodof Sholom had to stop bringing in Rabbi Goldberg due to their difficult financial situation. By 1950, Congregation Brith Achim formally aligned with the Conservative movement, joining the United Synagogue. Five years later, they moved to a new building on South Boulevard, where the synagogue currently stands. Virginia Governor Thomas Stanley spoke at the formal dedication, while Rabbi Solomon Jacobson, who served the congregation from 1951-1973, presided over the ceremony.

Throughout the 1950s, both congregations continued to face demographic pressures. In 1954, Rodof Sholom, with only 16 contributing members, reached out to Brith Achim regarding the possibility of a merger, citing their desire to preserve what remained of the Jewish community in Petersburg. While the president of Brith Achim, Dr. Julius H. Hopkins, reacted positively to the idea, not all of his congregants did. In a letter to the secretary of Rodof Sholom, Hopkins agreed that there was no longer a need for two separate congregations and that “a combined temple would soon lead to one of the strongest and most exemplary of Southern Jewish communities of our size.” However, after only one month of the trial period that was supposed to last six, Brith Achim officers realized that some of their members were unhappy with the new arrangement. In particular, they disliked the services, which included use of the Reform Union Prayer Book, organ music, optional skull caps, and English liturgy. When several members stopped attending services, Brith Achim decided to terminate the trial merger. Seven years later, in 1961, tensions arose again between the two congregations when Rabbi Ariel Goldberg sent out an invitation to Brith Achim’s congregants to attend the services he was leading at Rodeph Sholom. Brith Achim’s board wrote to their members that such an invitation was “a highly unethical and improper practice and as a trespass upon and disrespect to our own congregation and Rabbi.”

Rodof Sholom's temple is now a public library branch.

Rodof Sholom's temple is now a public library branch.

Throughout the 1960s, Rodof Sholom, with only 15 contributing members, continued to suffer financially. After deciding that a merger with Brith Achim was “impractical,” the board was forced to discuss the possible dissolution of the congregation. In October 1973, Rodof Sholom’s board voted to donate their synagogue to the city to be used as a branch library. They gave their Torahs to a new congregation in Richmond, Or Ami. Regarding the decision to donate their building, Rodof Sholom member Jacob Lavenstein explained, “we wanted to perpetuate the temple in the Petersburg community.” Today, the library endures as the Rodof Sholom Branch.

The Jewish Community in Petersburg Today

Although Rodof Sholom disbanded, Brith Achim continues to serve the small but vibrant Jewish community across the tri-city area of Petersburg, Colonial Heights, and Hopewell. Though no longer a member of the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, the congregation continues to worship in a Conservative style. Most of today’s congregants are older, retired merchants or working professionals who grew up attending Brith Achim. Indeed, many members have deep roots in Petersburg, often boasting family names of the historically well-known businesses in Petersburg, including Rosenstock, Hopkins, Jacobs, Ende, and Unger. Though most of these small businesses are no longer in operation, largely due to the rise of malls and chain stores in the 1970s, they remain strong in the memory of many Petersburg residents.

Congregation Brith Achim consists of about 100 households. Because there are very few families with school-aged children in the Petersburg Jewish community today, Brith Achim no longer runs a religious school on their own; the few young members instead travel to the Reform Congregation Beth Ahabah in Richmond to attend religious school. Rabbi Dennis Beck-Berman, who began to lead the congregation in 1993, helps train b'nei mitzvah students. Today, Brith Achim continues to preserve the family spirit that has long defined Petersburg’s Jewish community. As Rabbi Beck-Berman remarked at the congregation’s 100th anniversary in 2008, “People grew up with generations in the same town and synagogue. It gives family character to the congregation.”

Congregation Brith Achim consists of about 100 households. Because there are very few families with school-aged children in the Petersburg Jewish community today, Brith Achim no longer runs a religious school on their own; the few young members instead travel to the Reform Congregation Beth Ahabah in Richmond to attend religious school. Rabbi Dennis Beck-Berman, who began to lead the congregation in 1993, helps train b'nei mitzvah students. Today, Brith Achim continues to preserve the family spirit that has long defined Petersburg’s Jewish community. As Rabbi Beck-Berman remarked at the congregation’s 100th anniversary in 2008, “People grew up with generations in the same town and synagogue. It gives family character to the congregation.”