Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Pocahontas, Virginia

Pocahontas: Historical Overview

In the early 1880s, Pocahontas, Virginia, looked like much of central Appalachia: empty. Formidable mountains, primitive infrastructure, and a culture of subsistence farming meant that southwestern Virginia, southern West Virginia, and eastern Kentucky remained untouched by real estate developers and frontier bound pioneers in the century after independence. But the arrival of the railroad, and subsequently, the coalfields, would forever change Pocahontas and other Appalachian boomtowns.

The vision for a coal town hugging the Virginia-West Virginia border was the brainchild of Philadelphia railroad investors. The financiers incorporated the Norfolk and Western Railroad in 1881 and plotted its route through the heart of coal country. They saw lucrative mining potential at the sight of a creek and coal outcropping, the future sight of Pocahontas. The Southwest Virginia Improvement Company was established as a vehicle to develop coal and real estate projects in the area around Pocahontas and by 1883 the first coal shipments were hauled away by the trains.

African Americans and Hungarian immigrants flocked to towns like Pocahontas to work as miners while Jews filtered in with dreams of opening their own stores. They formed a small Jewish community that lasted into the 20th century.

The vision for a coal town hugging the Virginia-West Virginia border was the brainchild of Philadelphia railroad investors. The financiers incorporated the Norfolk and Western Railroad in 1881 and plotted its route through the heart of coal country. They saw lucrative mining potential at the sight of a creek and coal outcropping, the future sight of Pocahontas. The Southwest Virginia Improvement Company was established as a vehicle to develop coal and real estate projects in the area around Pocahontas and by 1883 the first coal shipments were hauled away by the trains.

African Americans and Hungarian immigrants flocked to towns like Pocahontas to work as miners while Jews filtered in with dreams of opening their own stores. They formed a small Jewish community that lasted into the 20th century.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Pocahontas

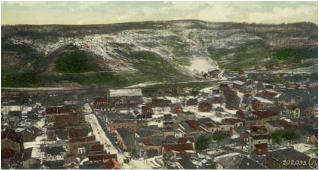

Bird's eye view of Pocahontas

Bird's eye view of Pocahontas

Early Settlers

German-born Michael Bloch and his wife arrived in Pocahontas in December 1882 and promptly bought land from a local real estate agent for a store. Jacob and Lena Baach, also German natives, came in 1883 after living in Virginia for several years. Their daughter and son-in-law followed them to Pocahontas in 1887. Bloch and Baach became business partners in the Bloch and Company department store which would become a fixture in town for the next 40 years. The Blochs and Baachs would leave an indelible mark on Pocahontas. Michael Bloch was the first master of the town’s Masonic Lodge while Jacob Baach was one of 23 charter members. In the 1910s and 1920s Jenny Baach, Jacob Baach’s daughter-in-law, was known as one of the town’s leading socialites and was given the honor of being the town census taker for the 1920 U.S. Census.

The two “founding” Jewish families made little effort to create a formal Jewish community. Michael Bloch was a member of a Methodist church. Many of his descendants, as well as Jacob Baach’s offspring, intermarried and did not raise their children Jewish. Though Baach and Bloch played a minimal role in Pocahontas’s Jewish community both still maintained a connection with their Jewish identity. Baach designated a portion of his estate to Jewish charities and Bloch had a subscription to the Jewish Publication Society of America. The Blochs and Baachs were the only German-Jewish families to settle in Pocahontas as relatively few German Jews made their home in the coalfields.

Most Jews who moved to the growing town were Eastern European immigrants who came to the U.S. as part of the large wave of immigration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By 1900, approximately 95 Jews lived in Pocahontas, including a rabbi listed in the 1900 Census. The Jewish population reached its highest in 1910 when 149 Jews were reported in 29 households, including the former and current rabbi as well as the Lithuanian-born J. Rappaport, who was listed as a preacher. Because Jewish families tended to be large in a town of mostly single coal miners, Jews comprised six percent of the population that year.

German-born Michael Bloch and his wife arrived in Pocahontas in December 1882 and promptly bought land from a local real estate agent for a store. Jacob and Lena Baach, also German natives, came in 1883 after living in Virginia for several years. Their daughter and son-in-law followed them to Pocahontas in 1887. Bloch and Baach became business partners in the Bloch and Company department store which would become a fixture in town for the next 40 years. The Blochs and Baachs would leave an indelible mark on Pocahontas. Michael Bloch was the first master of the town’s Masonic Lodge while Jacob Baach was one of 23 charter members. In the 1910s and 1920s Jenny Baach, Jacob Baach’s daughter-in-law, was known as one of the town’s leading socialites and was given the honor of being the town census taker for the 1920 U.S. Census.

The two “founding” Jewish families made little effort to create a formal Jewish community. Michael Bloch was a member of a Methodist church. Many of his descendants, as well as Jacob Baach’s offspring, intermarried and did not raise their children Jewish. Though Baach and Bloch played a minimal role in Pocahontas’s Jewish community both still maintained a connection with their Jewish identity. Baach designated a portion of his estate to Jewish charities and Bloch had a subscription to the Jewish Publication Society of America. The Blochs and Baachs were the only German-Jewish families to settle in Pocahontas as relatively few German Jews made their home in the coalfields.

Most Jews who moved to the growing town were Eastern European immigrants who came to the U.S. as part of the large wave of immigration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By 1900, approximately 95 Jews lived in Pocahontas, including a rabbi listed in the 1900 Census. The Jewish population reached its highest in 1910 when 149 Jews were reported in 29 households, including the former and current rabbi as well as the Lithuanian-born J. Rappaport, who was listed as a preacher. Because Jewish families tended to be large in a town of mostly single coal miners, Jews comprised six percent of the population that year.

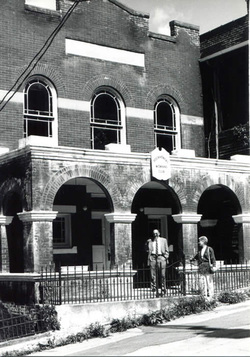

Ahavath Chesed's synagogue

Ahavath Chesed's synagogue

Jewish Businesses in Pocahontas

Jewish families dominated the dry goods and retail trades. Bloch and Company competed for customers against the Hyman Company, a dry goods store owned by Abe and Samuel Hyman. Other Jewish families owned confectionery shops, clothing stores and worked as tailors. A hefty percentage of Jewish families, 37 percent according to an analysis of Pocahontas’s Jewish population from 1910, owned liquor wholesale shops and saloons. Samuel Matz, Francis Goodman, Herman Milner, S. Cohen and brothers Solomon and Norman Kwass were just a few of the handful of Jews who ran saloons. L. Lazarus was a successful liquor and wine wholesaler who relocated to Pocahontas after West Virginia enacted prohibition laws in 1914. The Kwass Brothers also owned a bottling company and an ice manufacturing business.

Organized Jewish Life in Pocahontas

Efforts to establish Jewish religious organizations began in earnest with the arrival of Eastern European immigrants. The German-Jewish community had established a Jewish section within the city cemetery in 1890 but no formal congregation. As more Eastern European immigrants arrived, they formed Congregation Ahavath Chesed in 1892. Ahavath Chesed took on the Orthodox traditions of its congregants. It had a mikvah (ritual bath) and separate seating for men and women. The congregation obtained their own cemetery by 1903 on land near the state border. Jews from the nearby coal communities of Kimball and Keystone, West Virginia, were also buried at the cemetery, known locally as Hebrew Mountain.

Ahavath Chesed was one of central Appalachia’s strongest congregations during its heyday. The synagogue hosted five different full-time rabbis between the 1890s and 1910s. In 1912 the congregation purchased a building on land donated by the Milner family and held an elaborate dedication ceremony that filled the pews.

Scenes of a crowded synagogue and rabbis schlepping through Pocahontas’s raucous streets were short lived. The arrival of prohibition in Virginia in 1916 and the rise of nearby Bluefield, West Virginia, as a regional commercial and transportation hub doomed Pocahontas and its Jewish community. The town’s Jewish population sunk to 71 people in 1920, a significant decrease from its peak of 149 in 1910. The Kwass and Matz families followed the demographic shift and moved to Bluefield. Max Matz was born in Pocahontas and later established himself as a leading businessman and key member of the Republican Party in Bluefield in the 1920s and 1930s.

The Community Declines

The 1920s did not bring roaring times to Pocahontas or its Jewish community. The Jewish population had shriveled to the point that it was no longer possible to gather a minyan, the quorum of ten men required for prayer. The congregation disbanded by 1920. Only 14 Jews remained in Pocahontas by 1937. Though they had ceased to formally function, the Jewish community held onto its synagogue building until 1951 when it was sold to the Pocahontas Women’s Club. Before the sale of the synagogue, a rabbi in Bluefield unsuccessfully attempted to convince the remaining Jews to transfer the graves in the Jewish cemetery to Monte Vista Cemetery, a Jewish cemetery between Princeton, West Virginia, and Bluefield. In 1990 the building was sold again to a church.

Jewish families dominated the dry goods and retail trades. Bloch and Company competed for customers against the Hyman Company, a dry goods store owned by Abe and Samuel Hyman. Other Jewish families owned confectionery shops, clothing stores and worked as tailors. A hefty percentage of Jewish families, 37 percent according to an analysis of Pocahontas’s Jewish population from 1910, owned liquor wholesale shops and saloons. Samuel Matz, Francis Goodman, Herman Milner, S. Cohen and brothers Solomon and Norman Kwass were just a few of the handful of Jews who ran saloons. L. Lazarus was a successful liquor and wine wholesaler who relocated to Pocahontas after West Virginia enacted prohibition laws in 1914. The Kwass Brothers also owned a bottling company and an ice manufacturing business.

Organized Jewish Life in Pocahontas

Efforts to establish Jewish religious organizations began in earnest with the arrival of Eastern European immigrants. The German-Jewish community had established a Jewish section within the city cemetery in 1890 but no formal congregation. As more Eastern European immigrants arrived, they formed Congregation Ahavath Chesed in 1892. Ahavath Chesed took on the Orthodox traditions of its congregants. It had a mikvah (ritual bath) and separate seating for men and women. The congregation obtained their own cemetery by 1903 on land near the state border. Jews from the nearby coal communities of Kimball and Keystone, West Virginia, were also buried at the cemetery, known locally as Hebrew Mountain.

Ahavath Chesed was one of central Appalachia’s strongest congregations during its heyday. The synagogue hosted five different full-time rabbis between the 1890s and 1910s. In 1912 the congregation purchased a building on land donated by the Milner family and held an elaborate dedication ceremony that filled the pews.

Scenes of a crowded synagogue and rabbis schlepping through Pocahontas’s raucous streets were short lived. The arrival of prohibition in Virginia in 1916 and the rise of nearby Bluefield, West Virginia, as a regional commercial and transportation hub doomed Pocahontas and its Jewish community. The town’s Jewish population sunk to 71 people in 1920, a significant decrease from its peak of 149 in 1910. The Kwass and Matz families followed the demographic shift and moved to Bluefield. Max Matz was born in Pocahontas and later established himself as a leading businessman and key member of the Republican Party in Bluefield in the 1920s and 1930s.

The Community Declines

The 1920s did not bring roaring times to Pocahontas or its Jewish community. The Jewish population had shriveled to the point that it was no longer possible to gather a minyan, the quorum of ten men required for prayer. The congregation disbanded by 1920. Only 14 Jews remained in Pocahontas by 1937. Though they had ceased to formally function, the Jewish community held onto its synagogue building until 1951 when it was sold to the Pocahontas Women’s Club. Before the sale of the synagogue, a rabbi in Bluefield unsuccessfully attempted to convince the remaining Jews to transfer the graves in the Jewish cemetery to Monte Vista Cemetery, a Jewish cemetery between Princeton, West Virginia, and Bluefield. In 1990 the building was sold again to a church.

The Jewish Community in Pocahontas Today

King coal has long left this once rowdy and vibrant town, now home to a state prison and according to 2011 estimates, only 389 people. Despite the exodus of its population and closure of the mines, traces of the coal fields and the Jewish community remain. Pocahontas Coal Mine # 3 is now open to the public as a tourist attraction and the hundreds of graves in Russian, Polish, Italian, Hungarian and Hebrew still stand in the Pocahontas Cemetery. The last vestige of Jewish life lies off Route 120. There three trees, which according to local legend were imported from Palestine in the early 1900s, loom over the nearly two dozen graves in Pocahontas’s Jewish cemetery. Congregation Ahavath Sholom of Bluefield, West Virginia, has maintained the cemetery for decades and remains committed to the keeping the memory and legacy of the saloon keepers, store owners, and liquor distributors of the Pocahontas Jewish community alive.

Sources

Weiner, Deborah R. Coalfield Jews: An Appalachian History. University of Illinois Press, 2006.