Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Staunton, Virginia

Staunton: Historical Overview

|

Staunton, Virginia, Woodrow Wilson’s birthplace, is known for its quaint main streets and views of the rolling hills of the surrounding Shenandoah Valley. Plans for what media outlets have dubbed “one of America’s best small towns” date back to 1747 when early Augusta County settler Thomas Lewis designed a plan for what would become Staunton. After the Civil War, businesses boomed in the area, using the railroad to export locally grown crops.

There has been a Jewish community in Staunton for more than a century. |

Stories of the Jewish Community in Staunton

Early Settlers

The first Jewish settlers in Staunton were mostly merchants from German-speaking territories. By 1860 merchant Gabriel Hirsh had left his native Hessia for Staunton. Austrian born Isaac Witz organized his I .Witz & Bro. dry goods firm in 1865 after a stint as a store clerk in Mount Jackson, Virginia. Adolph Loeb arrived in Staunton from the Rhineland to work as a clerk in Staunton by 1870. Loeb, Hirsh, and the other German Jewish settlers did not organize a religious congregation initially, though they did have a Jewish social club by the mid-1870s.

The arrival of Alexander Hart in 1876 was the catalyst for creation of Staunton’s first Jewish congregation. Hart, a veteran of the Confederate army who nearly lost a leg at Antietam and was taken as a prisoner of war at Chancellorsville, came from a prominent Jewish family in New Orleans. He married Leonora Levy of Richmond and settled in Virginia after the war. He opened a dry goods store in Staunton in 1876. That same year, Hart was the driving force in the organization of Temple House of Israel, serving as its first president.

The first Jewish settlers in Staunton were mostly merchants from German-speaking territories. By 1860 merchant Gabriel Hirsh had left his native Hessia for Staunton. Austrian born Isaac Witz organized his I .Witz & Bro. dry goods firm in 1865 after a stint as a store clerk in Mount Jackson, Virginia. Adolph Loeb arrived in Staunton from the Rhineland to work as a clerk in Staunton by 1870. Loeb, Hirsh, and the other German Jewish settlers did not organize a religious congregation initially, though they did have a Jewish social club by the mid-1870s.

The arrival of Alexander Hart in 1876 was the catalyst for creation of Staunton’s first Jewish congregation. Hart, a veteran of the Confederate army who nearly lost a leg at Antietam and was taken as a prisoner of war at Chancellorsville, came from a prominent Jewish family in New Orleans. He married Leonora Levy of Richmond and settled in Virginia after the war. He opened a dry goods store in Staunton in 1876. That same year, Hart was the driving force in the organization of Temple House of Israel, serving as its first president.

Alexander Hart

Alexander Hart

Organized Jewish Life in Staunton

By the 1880s, the Jewish community was well known to citizens of Staunton. The Staunton Social Society had a Purim Ball and the Staunton Harmony Society had a concert at Kesher Hall in 1882. Both a Kesher Shel Barzel chapter and a B’nai B’rith lodge existed in 1885. On October 18, 1885, a notice in the newspaper alerted Staunton residents that “the stores of our Hebrew citizens will be closed from sundown this evening till sundown tomorrow evening…on this their Day of Atonement.”

In 1885 the trustees of Temple House Of Israel purchased the Hoover School on Kalorama Street for $600, the same year they joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. The purchase was financed through a loan from Loeb Bros. dry goods store. During the synagogue’s first meeting in their new building, Hart expressed how during the congregation’s initial years “God’s protective arm saved us from ruin” ultimately allowing them to assemble “…here this morning in this building, to be used as a synagogue, as [a] permanent home for the congregation.” At the inaugural meeting in the new building, members agreed to shutter their businesses by 7 pm on Fridays so they could participate in Friday night services. Hart was officially elected president of the congregation. The new building spurred the purchase of an organ in 1885 and land for a cemetery in 1886. By 1887 there was a discussion of a religious school in the congregation’s minutes. Hart served as the religious leader and president until his dry goods store failed and he moved to Norfolk in 1893.

After Hart’s departure in 1893, Louis Cohen and Albert Shultz led services for the congregation. Rabbi Edward Calisch of the Reform congregation Beth Ahaba in Richmond maintained a strong relationship with House of Israel. Throughout his career, Rabbi Calisch would visit Staunton periodically, helping to lead programs for children and officiating at funerals and weddings. House of Israel remained small in these early years, with only 12 families in 1900.

By the 1880s, the Jewish community was well known to citizens of Staunton. The Staunton Social Society had a Purim Ball and the Staunton Harmony Society had a concert at Kesher Hall in 1882. Both a Kesher Shel Barzel chapter and a B’nai B’rith lodge existed in 1885. On October 18, 1885, a notice in the newspaper alerted Staunton residents that “the stores of our Hebrew citizens will be closed from sundown this evening till sundown tomorrow evening…on this their Day of Atonement.”

In 1885 the trustees of Temple House Of Israel purchased the Hoover School on Kalorama Street for $600, the same year they joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations. The purchase was financed through a loan from Loeb Bros. dry goods store. During the synagogue’s first meeting in their new building, Hart expressed how during the congregation’s initial years “God’s protective arm saved us from ruin” ultimately allowing them to assemble “…here this morning in this building, to be used as a synagogue, as [a] permanent home for the congregation.” At the inaugural meeting in the new building, members agreed to shutter their businesses by 7 pm on Fridays so they could participate in Friday night services. Hart was officially elected president of the congregation. The new building spurred the purchase of an organ in 1885 and land for a cemetery in 1886. By 1887 there was a discussion of a religious school in the congregation’s minutes. Hart served as the religious leader and president until his dry goods store failed and he moved to Norfolk in 1893.

After Hart’s departure in 1893, Louis Cohen and Albert Shultz led services for the congregation. Rabbi Edward Calisch of the Reform congregation Beth Ahaba in Richmond maintained a strong relationship with House of Israel. Throughout his career, Rabbi Calisch would visit Staunton periodically, helping to lead programs for children and officiating at funerals and weddings. House of Israel remained small in these early years, with only 12 families in 1900.

The first home of Temple House of Israel.

The first home of Temple House of Israel.

Jewish Businesses in Staunton

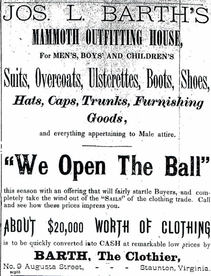

Merchants, grocery wholesalers, and stable owners took advantage of Staunton’s prime position on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad to send Augusta County’s agricultural products to the East Coast between the boom years of 1870 to 1900. The success of the railroad and its cottage industries coupled with the openings of White Star Mills, Bodley Wagon Works, and Putnam Organ Works plants in the 1890s made Staunton an attractive place to open a business for aspiring Jewish entrepreneurs. The clothing stores of Adolph Loeb, Joseph L. Barth, Louis Cohen and M.B. Oberdorfer were staples of South Augusta Street in 1887. In the 1895 city directory, six Jewish businesses concentrated in clothing, shoes and dry goods. A few Jewish-owned companies from the boom years evolved into mainstays of Staunton’s commercial scene.

By the 1890s, Isaac Witz had transformed himself from the owner of a single dry goods store into one of Staunton’s leading citizens. He sat on the board of directors of the Staunton Development Company, was an officer on the Staunton Chamber of Commerce, served on city council, started Witz Furniture Industries, and was a partner in the White Star Mills, a major flour mill that operated until 1966. Witz’s son Julius took over the furniture company and was mayor during the 1930s. He became an Episcopalian later in life yet still gave generously to Temple House of Israel.

Merchants, grocery wholesalers, and stable owners took advantage of Staunton’s prime position on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad to send Augusta County’s agricultural products to the East Coast between the boom years of 1870 to 1900. The success of the railroad and its cottage industries coupled with the openings of White Star Mills, Bodley Wagon Works, and Putnam Organ Works plants in the 1890s made Staunton an attractive place to open a business for aspiring Jewish entrepreneurs. The clothing stores of Adolph Loeb, Joseph L. Barth, Louis Cohen and M.B. Oberdorfer were staples of South Augusta Street in 1887. In the 1895 city directory, six Jewish businesses concentrated in clothing, shoes and dry goods. A few Jewish-owned companies from the boom years evolved into mainstays of Staunton’s commercial scene.

By the 1890s, Isaac Witz had transformed himself from the owner of a single dry goods store into one of Staunton’s leading citizens. He sat on the board of directors of the Staunton Development Company, was an officer on the Staunton Chamber of Commerce, served on city council, started Witz Furniture Industries, and was a partner in the White Star Mills, a major flour mill that operated until 1966. Witz’s son Julius took over the furniture company and was mayor during the 1930s. He became an Episcopalian later in life yet still gave generously to Temple House of Israel.

Ad for Joseph Barth's store, 1887

Ad for Joseph Barth's store, 1887

Prussian native Simon Barth settled in Staunton by the early 1870s and opened up the Augusta Clothing Hall. After he died a few years later, his brother Joseph Barth took over the store and renamed it J.L. Barth & Co. With the help of his longtime clerk L.G. Strauss, Barth turned J.L. Barth & Co. into Staunton’s premier clothing store. Dutch-born Abraham Weinberg was not intimidated by J.L. Barth when he arrived in Staunton in 1895. When the police officer heard that Weinberg wanted to open a clothing store, he told the aspiring entrepreneur to catch the train back to Baltimore since Barth had the trade wrapped up. Weinberg ignored the advice and started the Weinberg Clothing Company on South Augusta Street. By 1906, Weinberg had turned his store into one of Staunton’s top establishments. Customers flocked to the store for high-end outfits. After marrying Johanna Barth, a member of the Barth family, Weinberg Clothing Company merged with Barth’s Clothing Store in 1911 to form Barth Weinberg and Company. Amos and Jake Klotz were peddlers who opened a junk business in Staunton in 1899, because, according to legend, that was where their horse died. With the help of their younger brother Morris, the firm prospered and grew into a thriving scrap metal and hides and fur operation. In 1929, they constructed a large downtown building to house their business.

Charitable Efforts

The Jewish community took an active role in local philanthropic efforts. Albert Shultz and Fannie Strauss were two of the first officers of the Community Welfare League of Staunton and Augusta County. Temple House of Israel was one of the first organizations to donate money when the Community Welfare League formed in 1914. Shultz, L.G. Strauss and Abe Walters were original officers of the Augusta Chapter of the American Red Cross. In 1916 the Jewish community participated in the national effort to raise money for the American Jewish Relief Committee’s campaign to help Jews affected by World War I. Joseph Barth and L.G. Strauss piloted Staunton’s participation in the effort.

Charitable Efforts

The Jewish community took an active role in local philanthropic efforts. Albert Shultz and Fannie Strauss were two of the first officers of the Community Welfare League of Staunton and Augusta County. Temple House of Israel was one of the first organizations to donate money when the Community Welfare League formed in 1914. Shultz, L.G. Strauss and Abe Walters were original officers of the Augusta Chapter of the American Red Cross. In 1916 the Jewish community participated in the national effort to raise money for the American Jewish Relief Committee’s campaign to help Jews affected by World War I. Joseph Barth and L.G. Strauss piloted Staunton’s participation in the effort.

Temple House of Israel

Temple House of Israel

A Synagogue for House of Israel

By the 1920s, the small Staunton Jewish community was growing, with 108 people in 1927. With this growth, some pushed for a new synagogue for House of Israel. According to legend, Abraham Weinberg stood up in the old building in 1924 and blurted out “I’m tired of worshiping in something that looks like a warehouse.” He offered to donate half of the money for a “real synagogue” if the congregation raised the rest. A year later a cornerstone was laid for a new synagogue on a plot of land purchased from Mary Baldwin College on North Market Street. The congregation commissioned local architect T.J. Collins and Son for the unique Moorish revival building. The six stained glass windows in the building were done by Charles Connick Associates of Boston, one of the era’s most respected stained glass artists. The medieval style windows depict pomegranates, grapes, olives, figs and other plants that are native to Israel.

L.G. Strauss’s daughter, Fannie Strauss, known as Miss Fannie, was a longtime leader of Temple House of Israel. She navigated Staunton’s streets with a horse and buggy and taught German, Latin, literature, and math at Mary Baldwin College. Known for having the demeanor of a drill sergeant and calling visiting student rabbis “geeks,” Miss Fannie ran the religious school for decades and was the synagogue treasurer from 1942 until her death in 1973. If the synagogue was in danger of not generating enough revenue, Miss Fannie donated the amount needed to ensure the synagogue maintained met its budget.

While Temple House of Israel remained small, with only 20 contributing members in 1935, they were able to hire their a full-time rabbi by partnering with the Hebrew Friendship Congregation in 1936. Together, the two Reform congregations, which were located only 30 miles apart, hired Rabbi Leonard Rothstein, who served them both until 1942. After a two year gap without a rabbinic presence, the congregations hired Rabbi Pizer Jacobs in 1944. Jacobs stayed two years before leaving. Staunton would then be without a full-time rabbi for another 30 years.

For many years Temple House of Israel held Sunday morning services for students from Staunton Military Academy. A handful of Jewish cadets marched from campus to fulfill their school requirement of attending a religious service on Sundays. Some congregants believe that some of the cadets proclaimed themselves to be Jewish so they could attend the shortest service possible. Students from Augusta Military Academy and Fishburne Military Academy occasionally joined them. The congregation organized a youth group for the cadets and socials with local girls. Grateful that their sons could connect with their Jewish identity, families of Staunton Military Academy students gave generously to the synagogue.

By the 1920s, the small Staunton Jewish community was growing, with 108 people in 1927. With this growth, some pushed for a new synagogue for House of Israel. According to legend, Abraham Weinberg stood up in the old building in 1924 and blurted out “I’m tired of worshiping in something that looks like a warehouse.” He offered to donate half of the money for a “real synagogue” if the congregation raised the rest. A year later a cornerstone was laid for a new synagogue on a plot of land purchased from Mary Baldwin College on North Market Street. The congregation commissioned local architect T.J. Collins and Son for the unique Moorish revival building. The six stained glass windows in the building were done by Charles Connick Associates of Boston, one of the era’s most respected stained glass artists. The medieval style windows depict pomegranates, grapes, olives, figs and other plants that are native to Israel.

L.G. Strauss’s daughter, Fannie Strauss, known as Miss Fannie, was a longtime leader of Temple House of Israel. She navigated Staunton’s streets with a horse and buggy and taught German, Latin, literature, and math at Mary Baldwin College. Known for having the demeanor of a drill sergeant and calling visiting student rabbis “geeks,” Miss Fannie ran the religious school for decades and was the synagogue treasurer from 1942 until her death in 1973. If the synagogue was in danger of not generating enough revenue, Miss Fannie donated the amount needed to ensure the synagogue maintained met its budget.

While Temple House of Israel remained small, with only 20 contributing members in 1935, they were able to hire their a full-time rabbi by partnering with the Hebrew Friendship Congregation in 1936. Together, the two Reform congregations, which were located only 30 miles apart, hired Rabbi Leonard Rothstein, who served them both until 1942. After a two year gap without a rabbinic presence, the congregations hired Rabbi Pizer Jacobs in 1944. Jacobs stayed two years before leaving. Staunton would then be without a full-time rabbi for another 30 years.

For many years Temple House of Israel held Sunday morning services for students from Staunton Military Academy. A handful of Jewish cadets marched from campus to fulfill their school requirement of attending a religious service on Sundays. Some congregants believe that some of the cadets proclaimed themselves to be Jewish so they could attend the shortest service possible. Students from Augusta Military Academy and Fishburne Military Academy occasionally joined them. The congregation organized a youth group for the cadets and socials with local girls. Grateful that their sons could connect with their Jewish identity, families of Staunton Military Academy students gave generously to the synagogue.

Klotz Building

Klotz Building

The Post-War Years

The opening of American Safety Razor and General Electric plants in the mid-1950s in neighboring Waynesboro brought several new Jewish families to the congregation. As more Jewish professionals moved in to work for these industries, Staunton retained its base of Jewish merchants. Boston Electric Shoe Repair, run by the Sragovitz family since the 1920s, was one of the many prominent Jewish-owned stores on Main Street. Others included Finkel Furniture Company run by Nina and Milton Frankel, Albert and Esther Snyder’s Jewel Box jewelry store, Simon Sach’s fur shop, Julius and Sarah Lee Margolis’s shoe store. Long time staples such as Barth Weinberg and Klotz Brothers continued to be major fixtures of the business community.

Buoyed by the infusion of new Jewish families, Temple House of Israel began to grow after World War II. By 1962, 47 families belonged to the congregation, twice as many as 20 years earlier. Miss Fannie continued to run the school and was assisted by a new corps of teachers, including many recent arrivals. The Sisterhood had a growing membership and was known for its annual Coffee Klatch soup bowl fundraiser. The congregation relied on student rabbis from Hebrew Union College until 1975, when they once again partnered with Harrisonburg’s Congregation Beth El and jointly hired Rabbi E. Robert Kraus. According to Kraus’s contract, the rabbi would serve in Staunton for a third of the time. The shared rabbi agreement became permanent when Rabbi Douglas Weber was hired by both congregations in 1983. Rabbi Weber led Friday night services at each congregation on alternating weeks.

The opening of American Safety Razor and General Electric plants in the mid-1950s in neighboring Waynesboro brought several new Jewish families to the congregation. As more Jewish professionals moved in to work for these industries, Staunton retained its base of Jewish merchants. Boston Electric Shoe Repair, run by the Sragovitz family since the 1920s, was one of the many prominent Jewish-owned stores on Main Street. Others included Finkel Furniture Company run by Nina and Milton Frankel, Albert and Esther Snyder’s Jewel Box jewelry store, Simon Sach’s fur shop, Julius and Sarah Lee Margolis’s shoe store. Long time staples such as Barth Weinberg and Klotz Brothers continued to be major fixtures of the business community.

Buoyed by the infusion of new Jewish families, Temple House of Israel began to grow after World War II. By 1962, 47 families belonged to the congregation, twice as many as 20 years earlier. Miss Fannie continued to run the school and was assisted by a new corps of teachers, including many recent arrivals. The Sisterhood had a growing membership and was known for its annual Coffee Klatch soup bowl fundraiser. The congregation relied on student rabbis from Hebrew Union College until 1975, when they once again partnered with Harrisonburg’s Congregation Beth El and jointly hired Rabbi E. Robert Kraus. According to Kraus’s contract, the rabbi would serve in Staunton for a third of the time. The shared rabbi agreement became permanent when Rabbi Douglas Weber was hired by both congregations in 1983. Rabbi Weber led Friday night services at each congregation on alternating weeks.

The Jewish Community in Staunton Today

Interior of Temple House of Israel

Interior of Temple House of Israel

Today, Staunton is one of the Shenandoah Valley’s most picturesque towns. The mom and pop storefronts on its main streets brings back memories of when the downtown area was teeming with Jewish businesses. Most of them are gone now. The Witz building is home to corporate offices while the Klotz building now houses a glass blowing studio. Though the days of the Jewish merchant are gone, the Jewish presence in Staunton continues with Temple House of Israel, which remains active.