Oral History: Technology

|

Technological issues have to be a concern for any oral historian, whether a dedicated volunteer or full-time professional. In fact, addressing questions about new technologies is one of the major goals of this manual; because, while the emergence of digital audio recorders and video cameras makes collecting and sharing oral histories easier than ever, there are a number of things that researchers need to know to create durable and high quality records for the future.

While the manual deals primarily with audio issues, successful use of video raises all of these questions and more. This section begins with an overview of key terms that will help explain digital recording technology, and proceeds through discussions of the advantages of digital recordings, appropriate recording devices for oral history, the issue of internal versus external microphones, and standards for digital audio. The section closes with recommendations for purchasing interview equipment and further resources for making these important decisions |

|

Key Terms

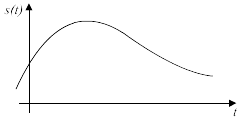

Analog: this term refers to earlier methods of recording —both audio and visual—that transform some kind of input into a physical code like on a wax cylinder recording or vinyl record, or onto magnetic tape. Cassette tapes are the most recent format for analog recording. Digital: digital technologies use electronic codes to create recordings. Unlike analog, this requires recorders to capture information in discrete pieces, individual samples of sound or picture. Most people have become familiar with digital audio through compact discs (CDs) or subsequent computer-based media formats, particularly mP3 files. See the graphic to the right for a visualization of analog and digital recordings. Born digital: a recording that was originally made in a digital format, rather than one that started as an analog (likely tape) recording and was later captured to a digital format. |

File format: like other audio and visual documents, digital recordings are stored in particular formats that allow them to be played back with consistent results. Because these recordings are captured as files (sets of information stored on a computer or other digital device rather than on a reel of tape) the format of the recording is noted by the last three letters on the file name. For digital audio, some of the most common suffixes are .mp3 (em pee three) and .wav (wave). There are a few important considerations to be made when choosing a format in which to make a digital recording.

Sample rate: given in kilohertz (KHz), this is a measure of how many thousands of audio samples are taken in a single second for each recording channel. The current standard for CDs is 44.1 KHz—44,100 samples per second for a single track or channel of recorded sound. That sounds like a lot, but some archivists advocate an even higher sample rate, up to 96KHz. Sample rate and bit depth, together, determine the level of detail for a digital audio file.

Bit resolution: also called bit depth, this refers to how the level of sensitivity and detail in each tiny sample of sound. The standard unit of measurement here is the “bit”. A CD-quality recording should have a resolution of 16 bits, but many archives prefer a depth of 24 bits.

Advantages of Recording Interviews in Digital Format

There are several important reasons that you or your organization should, if possible, use digital recording formats for new additions to your oral history collection.

Recording Devices

Researchers of all sorts, historians or not, often make use of small digital recorders that sell for under $100. While these devices create intelligible recordings, they may lack the quality of sound that professional audio archivists promote. Two issues explain the limitations of these recorders: microphone quality and file format.

Generally, the small digital recorders include microphone inputs, so that users do have the option of using an external microphone. For the most part, however, the hardware that receives the microphone signal is not of a high enough caliber to take advantage of a good microphone. Though the built-in microphones for these devices can capture the human voice clear enough to understand, they simply do not provide high quality sound, in terms of either clarity or richness.

There are two reasons that the file formats used by low-end recorders cause problems. First, many popular devices record only in .mp3 or other compressed formats. While .mp3 files are highly useful for disseminating audio recordings because they take up less memory, they compromise sound quality, especially if a recording will be edited later. This is because a compressed file is created through an automated process that simplifies higher quality files, representing more complex audio and visual information at lower resolution. Though the lost information may be difficult or even impossible to hear, a recording will often become increasingly degraded as it is edited and re-encoded in a compressed format. Second, some recording devices use closed formats, limiting creators’ software options for editing, or even reviewing, their own recordings. In order to create recordings with the potential for widespread and continued access, it is best to choose formats that later users will likely be able to access for both playback and editing.

In order to create high quality recordings according to appropriate standards, we urge all oral historians, even non-professionals, to obtain the very best equipment possible. The chapter concludes with more specific recommendations, but expect to spend $150 (minimum) for a low-level recorder that meets the basic 44.1 kHz/24 bit standard and significantly more for a higher end device.

External Microphones

In the past, it was very difficult to create a good recording with an internal microphone, because the moving parts in a tape recorder created a variety of distracting noises. Although these sounds are hardly noticeable to the ear during recording, their proximity to the built-in microphone mean that they are impossible to miss during payback of the tape. Additionally, any recorder with internal microphones will pick up handling noise—sounds created or altered by the interviewer as he or she moves the machine or changes its settings.

With the advent of ever-improving handheld digital recorders, it is possible to capture decent audio using only built-in microphones, but the sound quality will depend entirely on the quality of the device in question and its various components. While some researchers feel comfortable with the internal microphones on the newer machines, others still advocate the use of external microphones for better sound, and because distancing the microphone from the recorder eliminates the issue of handling noise and the subtle but still-present buzz or hum that comes with digital recorders.

If you are looking for an external microphone, a mono dynamic mic in a quality stand should do the job. These single-channel microphones will be durable and do not require external power from batteries or the recorder itself. Commonly recommended models include the Audio Technica AT804 and the Shure VP64A, each of which may be available for under $100.

A lavaliere microphone, the small ones that you see clipped to the collar or lapel of television interviewees, will not capture as wide a range of sound, but does not require narrators to speak toward a stationary microphone. Also, a speaker may open up more than in front of a more obtrusive mic. These are almost certainly the way to go if you or your organization is conducting video interviews. Prices range from $120 or more for an AKG C417 to over $400 for a top shelf lavaliere microphone. For more information on microphone types, as well as recommendations and reviews, see these websites:

Oade Brothers Audio: a Georgia based company whose website provides very helpful information. Follow either the “Microphone FAQ” or “Recording FAQ” button in the left side menu.

The Vermont Folklife Center, Digital Audio Field Recording Equipment Guide: folklorist and audio expert Andy Kovolos opines on all sorts of audio equipment.

Microphone Data: a comprehensive source for technical information on current microphones, the website also links to articles by audio industry experts. Requires free registration.

Standards

Current literature on best practices for archiving audio materials recommends storing digital sound files in .wav format at a quality of at least 44.1 kHz/24 bits, although 16 bit recordings may be sufficient. While the 44.1 kHz standard should be adequate for oral history recordings, many archives are moving toward an 88.1 or 96 kHz sample rate. While this requires greater digital storage space and may not provide audibly improved sound, technological advances continue to make higher standards more attainable.

For more thorough discussions of standards for recording, capturing and archiving digital audio, we highly recommend both the National Recording Preservation Board's, Capturing Analog Sound for Digital Preservation and Digital Audio Best Practices Version 2.1, an online publication by the Bibliographic Center for Research's Collaborative Digitization Project. Both of these documents are available in .pdf format through the above links and were created in 2006. While they are aimed more at archiving digitized copies of analog recordings, much of the material will prove useful for researchers working with new digital recordings.

Recommendations

This list of equipment comes second-hand from a few sources, particularly a list of reviews written by Andy Kolovos at the Vermont Folklife Center. Though Kolovos’ field recording standards are beyond the reach of most locally funded researchers, his takes on various recorders give a good sense of their strengths and weaknesses.

The following devices are all solid state recorders; they store newly created audio files on removable data cards that are designed to store information temporarily. It is necessary, therefore, to implement an archive strategy that uploads interviews to a computer and creates backup copies. You will either connect your recorder directly to the computer or remove the data card from the recorder and place it in a card reading device that is linked to the computer. Following upload, the data card can be cleared and used again. See the Vermont Folklife Center's in-depth explanation of solid state recorders for more details.

- Compressed formats: compressed formats use sophisticated computer processes to eliminate non-essential information from digital audio, thereby decreasing the storage space required for a recording. While the recording may not lose quality in the ears of a casual listener, compressed audio does not reproduce sound as faithfully, and can degrade as it is altered and re-compressed during editing. Compressed versions of non-compressed audio recordings are very useful, however, for online distribution or integrating into a website.

- Proprietary formats: often, digital recording formats have been developed by companies that hold a patent on the method by which visual and auditory signals are turned into digital code. As long as the patent remains valid, the owner can use licensing restrictions to determine if and how software by other developers can open or modify files in that format.

- Closed/open formats: Sometimes, the originators of proprietary formats tightly control how the code is used, so that files in a given format can only be opened or edited using that company’s software. This is what is known as a closed format. Other formats are more or less open; while they may be developed by companies like IBM, Microsoft, or Apple, these types of files can be opened or edited in a variety of programs according to specific licensing agreements. Many widely-used file formats in this category have become standard. So, while there are still some drawbacks to this arrangement, the relative ubiquity of these file types make them convenient for editing and practical for archiving in the foreseeable future.

Sample rate: given in kilohertz (KHz), this is a measure of how many thousands of audio samples are taken in a single second for each recording channel. The current standard for CDs is 44.1 KHz—44,100 samples per second for a single track or channel of recorded sound. That sounds like a lot, but some archivists advocate an even higher sample rate, up to 96KHz. Sample rate and bit depth, together, determine the level of detail for a digital audio file.

Bit resolution: also called bit depth, this refers to how the level of sensitivity and detail in each tiny sample of sound. The standard unit of measurement here is the “bit”. A CD-quality recording should have a resolution of 16 bits, but many archives prefer a depth of 24 bits.

Advantages of Recording Interviews in Digital Format

There are several important reasons that you or your organization should, if possible, use digital recording formats for new additions to your oral history collection.

- Digital recordings do not lose quality as copies are made.

- Digital recordings (audio) can be transferred from one recording or storage device to another in a fraction of their actual duration.

- Digital recordings can be shared over the internet.

- Digital recordings are simpler to edit, whether trimming for excerpts or altering for quality, and the editing process will not damage the original copy.

Recording Devices

Researchers of all sorts, historians or not, often make use of small digital recorders that sell for under $100. While these devices create intelligible recordings, they may lack the quality of sound that professional audio archivists promote. Two issues explain the limitations of these recorders: microphone quality and file format.

Generally, the small digital recorders include microphone inputs, so that users do have the option of using an external microphone. For the most part, however, the hardware that receives the microphone signal is not of a high enough caliber to take advantage of a good microphone. Though the built-in microphones for these devices can capture the human voice clear enough to understand, they simply do not provide high quality sound, in terms of either clarity or richness.

There are two reasons that the file formats used by low-end recorders cause problems. First, many popular devices record only in .mp3 or other compressed formats. While .mp3 files are highly useful for disseminating audio recordings because they take up less memory, they compromise sound quality, especially if a recording will be edited later. This is because a compressed file is created through an automated process that simplifies higher quality files, representing more complex audio and visual information at lower resolution. Though the lost information may be difficult or even impossible to hear, a recording will often become increasingly degraded as it is edited and re-encoded in a compressed format. Second, some recording devices use closed formats, limiting creators’ software options for editing, or even reviewing, their own recordings. In order to create recordings with the potential for widespread and continued access, it is best to choose formats that later users will likely be able to access for both playback and editing.

In order to create high quality recordings according to appropriate standards, we urge all oral historians, even non-professionals, to obtain the very best equipment possible. The chapter concludes with more specific recommendations, but expect to spend $150 (minimum) for a low-level recorder that meets the basic 44.1 kHz/24 bit standard and significantly more for a higher end device.

External Microphones

In the past, it was very difficult to create a good recording with an internal microphone, because the moving parts in a tape recorder created a variety of distracting noises. Although these sounds are hardly noticeable to the ear during recording, their proximity to the built-in microphone mean that they are impossible to miss during payback of the tape. Additionally, any recorder with internal microphones will pick up handling noise—sounds created or altered by the interviewer as he or she moves the machine or changes its settings.

With the advent of ever-improving handheld digital recorders, it is possible to capture decent audio using only built-in microphones, but the sound quality will depend entirely on the quality of the device in question and its various components. While some researchers feel comfortable with the internal microphones on the newer machines, others still advocate the use of external microphones for better sound, and because distancing the microphone from the recorder eliminates the issue of handling noise and the subtle but still-present buzz or hum that comes with digital recorders.

If you are looking for an external microphone, a mono dynamic mic in a quality stand should do the job. These single-channel microphones will be durable and do not require external power from batteries or the recorder itself. Commonly recommended models include the Audio Technica AT804 and the Shure VP64A, each of which may be available for under $100.

A lavaliere microphone, the small ones that you see clipped to the collar or lapel of television interviewees, will not capture as wide a range of sound, but does not require narrators to speak toward a stationary microphone. Also, a speaker may open up more than in front of a more obtrusive mic. These are almost certainly the way to go if you or your organization is conducting video interviews. Prices range from $120 or more for an AKG C417 to over $400 for a top shelf lavaliere microphone. For more information on microphone types, as well as recommendations and reviews, see these websites:

Oade Brothers Audio: a Georgia based company whose website provides very helpful information. Follow either the “Microphone FAQ” or “Recording FAQ” button in the left side menu.

The Vermont Folklife Center, Digital Audio Field Recording Equipment Guide: folklorist and audio expert Andy Kovolos opines on all sorts of audio equipment.

Microphone Data: a comprehensive source for technical information on current microphones, the website also links to articles by audio industry experts. Requires free registration.

Standards

Current literature on best practices for archiving audio materials recommends storing digital sound files in .wav format at a quality of at least 44.1 kHz/24 bits, although 16 bit recordings may be sufficient. While the 44.1 kHz standard should be adequate for oral history recordings, many archives are moving toward an 88.1 or 96 kHz sample rate. While this requires greater digital storage space and may not provide audibly improved sound, technological advances continue to make higher standards more attainable.

For more thorough discussions of standards for recording, capturing and archiving digital audio, we highly recommend both the National Recording Preservation Board's, Capturing Analog Sound for Digital Preservation and Digital Audio Best Practices Version 2.1, an online publication by the Bibliographic Center for Research's Collaborative Digitization Project. Both of these documents are available in .pdf format through the above links and were created in 2006. While they are aimed more at archiving digitized copies of analog recordings, much of the material will prove useful for researchers working with new digital recordings.

Recommendations

This list of equipment comes second-hand from a few sources, particularly a list of reviews written by Andy Kolovos at the Vermont Folklife Center. Though Kolovos’ field recording standards are beyond the reach of most locally funded researchers, his takes on various recorders give a good sense of their strengths and weaknesses.

The following devices are all solid state recorders; they store newly created audio files on removable data cards that are designed to store information temporarily. It is necessary, therefore, to implement an archive strategy that uploads interviews to a computer and creates backup copies. You will either connect your recorder directly to the computer or remove the data card from the recorder and place it in a card reading device that is linked to the computer. Following upload, the data card can be cleared and used again. See the Vermont Folklife Center's in-depth explanation of solid state recorders for more details.

Marantz PMD661

This is one of the best digital recorders available for under $1,000, especially for use with external microphones. It has a somewhat simpler interface than the Fostex FR-2LE. The PMD661 retails for about $600. Buyers should also budget for a large SD data card ($17-$30 for a 4GB card) and one or more external microphones.

This is one of the best digital recorders available for under $1,000, especially for use with external microphones. It has a somewhat simpler interface than the Fostex FR-2LE. The PMD661 retails for about $600. Buyers should also budget for a large SD data card ($17-$30 for a 4GB card) and one or more external microphones.

Fostex FR-2LE

Andy Kolovos prefers this machine to the Marantz PMD661, because it offers more refined control of recorded audio. For non-experts, the extra features may prove somewhat daunting, though. The Fostex uses a CF card, a larger storage card for digital files that is no longer as popular as the smaller SD options. The device costs around $500 and will work very well with external microphones. A 4GB CF card costs $20-50 and will store 4.5 hours of audio at 44.1 kHz/24 bits, likely allowing researchers to complete two full interviews before moving files to a long-term hard drive.

Andy Kolovos prefers this machine to the Marantz PMD661, because it offers more refined control of recorded audio. For non-experts, the extra features may prove somewhat daunting, though. The Fostex uses a CF card, a larger storage card for digital files that is no longer as popular as the smaller SD options. The device costs around $500 and will work very well with external microphones. A 4GB CF card costs $20-50 and will store 4.5 hours of audio at 44.1 kHz/24 bits, likely allowing researchers to complete two full interviews before moving files to a long-term hard drive.

Marantz PMD620

The PMD620 was designed to compete with recorders like the Edirol R-09HR—decent quality devices that feature 1/8 inch (3.5mm) microphone jacks instead of higher quality XLR inputs. The internal microphones will suffice for many users, and external mics will require an adapter. The PMD620 can be found online for between $340 and $400. It features a small internal speaker. Though this device is likely to cost a bit more than the Edirol R-09HR, it comes with a higher recommendation from the Andy Kovolos, in part because of the Marantz company’s reputation for stellar customer service.

The PMD620 was designed to compete with recorders like the Edirol R-09HR—decent quality devices that feature 1/8 inch (3.5mm) microphone jacks instead of higher quality XLR inputs. The internal microphones will suffice for many users, and external mics will require an adapter. The PMD620 can be found online for between $340 and $400. It features a small internal speaker. Though this device is likely to cost a bit more than the Edirol R-09HR, it comes with a higher recommendation from the Andy Kovolos, in part because of the Marantz company’s reputation for stellar customer service.

Edirol R-09HR

An upgrade from the earlier R-09 model, the R-09HR lists for $400, but appears to be available for $300 or less. New features include an internal speaker and a remote control. The remote may be useful for changing settings without adding handling noise, while I doubt that the small speaker will provide enough sound quality for monitoring audio in the field.

An upgrade from the earlier R-09 model, the R-09HR lists for $400, but appears to be available for $300 or less. New features include an internal speaker and a remote control. The remote may be useful for changing settings without adding handling noise, while I doubt that the small speaker will provide enough sound quality for monitoring audio in the field.

Samson Zoom H2

At the bottom end of this list is the Zoom H2, which is available online for well below its manufacturer’s suggested retail price of $335. For $150 or less, this device offers much better sound and options than a basic mp3 recorder, but will probably not match its pricier competitors in durability and sound quality. Additionally, the Zoom H2 does not have good enough components to take advantage of a quality external microphone. Compared to the Edirol R-09HR, it does have the advantage of an included stand and a standard threaded hole for mounting on a digital camera tripod. Despite its potential drawbacks, the affordable price makes the Zoom H2 an attractive candidate for audio interview projects, especially for student or community groups working with local oral history.

At the bottom end of this list is the Zoom H2, which is available online for well below its manufacturer’s suggested retail price of $335. For $150 or less, this device offers much better sound and options than a basic mp3 recorder, but will probably not match its pricier competitors in durability and sound quality. Additionally, the Zoom H2 does not have good enough components to take advantage of a quality external microphone. Compared to the Edirol R-09HR, it does have the advantage of an included stand and a standard threaded hole for mounting on a digital camera tripod. Despite its potential drawbacks, the affordable price makes the Zoom H2 an attractive candidate for audio interview projects, especially for student or community groups working with local oral history.

Modifications

Audio recording experts have developed hardware modifications that improve audio recorders. The Fostex FR-2LE and both of the Marantz models listed above are available from Oade Brothers Audio with upgrades to various components of the stock models. To learn more about these options, and to find more information on microphone selection and other issues, visit their website.