Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Sumter, South Carolina

Overview >> South Carolina >> Sumter

Sumter: Historical Overview

|

Sumter’s early Jewish community, which began taking shape in the 1820s, included some of the leading figures in the state’s Jewish history. The town’s first Jewish settler, Mark Solomons, arrived sometime between 1815 and 1820. Scions from such prominent Charleston families as Moses and Harby came to Sumter in the decades before the Civil War, while members of the Cohen and Moïse families settled there after the war. Several of the newcomers and their descendants rose to economic and political prominence. Despite this, Sumter did not develop an organized Jewish community until the late 19th century, when Jewish immigrants from Europe came to the small town in the center of South Carolina. Sumter’s Jewish population reached a peak in the mid-20th century, and then, as in small towns across the nation, began an inexorable decline.

|

Originally named Sumterville, the small village grew slowly around a courthouse and jail established at the turn of the 19th century. Named for General Thomas “the Gamecock” Sumter, a Revolutionary War hero, the village was part of the new Sumter District situated at the inland border of the coastal plain where swampy land gave way to high hills. Beginning in the 1740s, Scots-Irish farmers and wealthy planters populated the high ground first, as part of the British government’s plan to develop a buffer between the coastal towns and the Native Americans of the backcountry. The district’s economy was based on agriculture, initially tobacco, rice, and indigo. Cotton replaced rice and indigo as the primary wealth-producing crop in the 19th century, while the lumber business continued to flourish. Railroad connections in the mid-19th century further stimulated the thriving local economy, and by 1860 Sumter District had the greatest per capita wealth in all of South Carolina. Sumterville was incorporated in 1845. Ten years later its name was shortened to Sumter.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Sumter

Octavia Harby Moses

Octavia Harby Moses

Early Settlers

Jews played a significant role in the 19th century growth of the district. Besides forming a sizable community in Sumter, they settled in midlands towns such as Camden, Bishopville, Darlington, Mayesville, Manville, Summerton, and Manning.

Franklin J. Moses was a native of Charleston who settled in Sumterville in the mid-1820s. He established a law practice in which his brother Montgomery soon joined him. Franklin served as a state senator in the years before the Civil War and as the Chief Justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court in the post-war years. His acceptance of the Chief Justice position in 1865 under the new Reconstruction government caused some consternation among his friends and colleagues, but his reputation as a man of integrity remained intact. From 1851 until his death in 1877, he served as a trustee and a Law Professor at South Carolina College (later University of South Carolina). Franklin, whose grandfather, Myer Moses, came to Charleston in the 1760s, was reportedly not a practicing Jew. He married a Christian and raised his son, Franklin Jr., in the Episcopal Church. Franklin J. Moses, Jr., went on to become a controversial Reconstruction-era governor of South Carolina.

Octavia Harby Moses and Andrew Jackson Moses, both natives of Charleston, moved to Sumterville in 1842. Andrew was a first cousin of Franklin J. Moses, Sr., and Octavia was the daughter of Reform leader, Isaac Harby. The couple purchased 42 acres in the heart of the village and built a home on the property in 1848. This dwelling, later known as the Williams-Brice home, currently houses the Sumter County Museum. Andrew and Octavia, whose backgrounds were rooted in Charleston’s Reform movement, reportedly were “constant in their worship.” Lacking a local synagogue, they took responsibility for their children’s religious upbringing, observing the Sabbath and the holidays through family prayer.

Jews played a significant role in the 19th century growth of the district. Besides forming a sizable community in Sumter, they settled in midlands towns such as Camden, Bishopville, Darlington, Mayesville, Manville, Summerton, and Manning.

Franklin J. Moses was a native of Charleston who settled in Sumterville in the mid-1820s. He established a law practice in which his brother Montgomery soon joined him. Franklin served as a state senator in the years before the Civil War and as the Chief Justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court in the post-war years. His acceptance of the Chief Justice position in 1865 under the new Reconstruction government caused some consternation among his friends and colleagues, but his reputation as a man of integrity remained intact. From 1851 until his death in 1877, he served as a trustee and a Law Professor at South Carolina College (later University of South Carolina). Franklin, whose grandfather, Myer Moses, came to Charleston in the 1760s, was reportedly not a practicing Jew. He married a Christian and raised his son, Franklin Jr., in the Episcopal Church. Franklin J. Moses, Jr., went on to become a controversial Reconstruction-era governor of South Carolina.

Octavia Harby Moses and Andrew Jackson Moses, both natives of Charleston, moved to Sumterville in 1842. Andrew was a first cousin of Franklin J. Moses, Sr., and Octavia was the daughter of Reform leader, Isaac Harby. The couple purchased 42 acres in the heart of the village and built a home on the property in 1848. This dwelling, later known as the Williams-Brice home, currently houses the Sumter County Museum. Andrew and Octavia, whose backgrounds were rooted in Charleston’s Reform movement, reportedly were “constant in their worship.” Lacking a local synagogue, they took responsibility for their children’s religious upbringing, observing the Sabbath and the holidays through family prayer.

Andrew Jackson Moses

Andrew Jackson Moses

The Moses family members were loyal South Carolinians during the Civil War. Although he owned 16 slaves, Andrew did not support secession. Once the state made the decision to secede, however, he joined the Home Guards and was stationed on the coast near Georgetown. Five of his sons served in the Confederate Army as well. Andrew was a farmer and a businessman, and with Octavia’s assistance, the family was able to get back on its feet after the war. Octavia, who had been pro-secession from the start and supported the war effort in every way she could, established the Ladies Monumental Association in 1869. As president, and the only female officer of the association, she led the fundraising drive to build a monument honoring the South’s fallen soldiers.

Moses Levi was another early Jewish settler of the area, arriving in the United States from Bavaria in the 1840s. By 1856, he had moved to Manning, 15 miles from Sumter, to open a mercantile store. After serving in the army during the Civil War, he made a fortune in the dry goods business. Upon his death in 1898, his wife and children paid tribute to him by purchasing the Manning Collegiate Institute, which they renamed the Moses Levi Memorial Institute and presented as a gift to the town of Manning. The institute was a college preparatory school for grades one through ten. When Moses’ wife, Hannah, died a few years later, the Levi children provided the town with an endowment of $1,000 towards the Hannah Levi Memorial Library.

Moses Levi was another early Jewish settler of the area, arriving in the United States from Bavaria in the 1840s. By 1856, he had moved to Manning, 15 miles from Sumter, to open a mercantile store. After serving in the army during the Civil War, he made a fortune in the dry goods business. Upon his death in 1898, his wife and children paid tribute to him by purchasing the Manning Collegiate Institute, which they renamed the Moses Levi Memorial Institute and presented as a gift to the town of Manning. The institute was a college preparatory school for grades one through ten. When Moses’ wife, Hannah, died a few years later, the Levi children provided the town with an endowment of $1,000 towards the Hannah Levi Memorial Library.

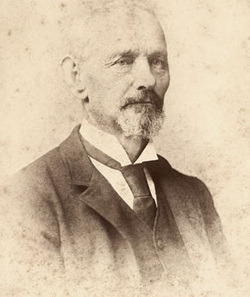

Edwin Warren Moise

Edwin Warren Moise

A Growing Community

Sumter’s population, already swelled by refugees fleeing Charleston during the Civil War, continued to grow after the conflict ended. Octavia Cohen, daughter of planter Marx E. Cohen of Charleston, moved with her family to Sumter where she would meet her future husband, Altamont Moses. Octavia was as involved in community affairs as was her husband. Altamont was active in the Democratic Party, held government positions, and served on a number of boards. He was also president of the Hebrew Benevolent Society and the Sumter Society of Israelites. Octavia, who raised six children, was a founding member of the local Daughters of the Confederacy and held office in both the state and local chapters. She was instrumental in supporting charitable pursuits through Sumter’s Civic League and Temple Sinai’s Ladies Aid Society, which she served as president.

Edwin Warren Moïse, born in 1832 in Charleston, settled in Columbus, Georgia, but moved to Sumter after the Civil War. He did not support secession, yet he rallied a mounted company of Confederates, the Moise Rangers, in 1861, using $10,000 of his own money. He advanced through the ranks of the army to become a major. After the war, he practiced law in Sumter, and farmed as well. In 1876 he was elected Adjutant and Inspector General on Governor Wade Hampton’s “redemption” ticket, earning him the moniker “General.” Moïse was active in Democratic Party politics, but lost two bids to win a congressional seat. His 1902 funeral attested to his standing in the community. Businesses and schools closed in his honor and City Hall’s bell tolled for the cortege, which was accompanied by the Sumter Light Infantry and Sumter Military Academy cadets. Hundreds of people from all over the state attended the ceremony, conducted by Rabbi Barnett Elzas of Charleston’s Beth Elohim.

Other families that settled in Sumter after the Civil War included the Phelps, Levys, and Barnetts. B. J. Barnett, who is believed to have emigrated from Estonia, arrived in South Carolina before the war, fought for the Confederate Army, and married Zelda Loryea of Charleston. Like many Eastern European immigrants, he peddled before becoming a storekeeper in Manville, a small town about 20 miles north of Sumter. He acquired hundreds of acres of land near his store for cotton farming. In 1880, accompanied by three of his grown children, Barnett moved to Sumter where they opened a general store.

Sumter’s population, already swelled by refugees fleeing Charleston during the Civil War, continued to grow after the conflict ended. Octavia Cohen, daughter of planter Marx E. Cohen of Charleston, moved with her family to Sumter where she would meet her future husband, Altamont Moses. Octavia was as involved in community affairs as was her husband. Altamont was active in the Democratic Party, held government positions, and served on a number of boards. He was also president of the Hebrew Benevolent Society and the Sumter Society of Israelites. Octavia, who raised six children, was a founding member of the local Daughters of the Confederacy and held office in both the state and local chapters. She was instrumental in supporting charitable pursuits through Sumter’s Civic League and Temple Sinai’s Ladies Aid Society, which she served as president.

Edwin Warren Moïse, born in 1832 in Charleston, settled in Columbus, Georgia, but moved to Sumter after the Civil War. He did not support secession, yet he rallied a mounted company of Confederates, the Moise Rangers, in 1861, using $10,000 of his own money. He advanced through the ranks of the army to become a major. After the war, he practiced law in Sumter, and farmed as well. In 1876 he was elected Adjutant and Inspector General on Governor Wade Hampton’s “redemption” ticket, earning him the moniker “General.” Moïse was active in Democratic Party politics, but lost two bids to win a congressional seat. His 1902 funeral attested to his standing in the community. Businesses and schools closed in his honor and City Hall’s bell tolled for the cortege, which was accompanied by the Sumter Light Infantry and Sumter Military Academy cadets. Hundreds of people from all over the state attended the ceremony, conducted by Rabbi Barnett Elzas of Charleston’s Beth Elohim.

Other families that settled in Sumter after the Civil War included the Phelps, Levys, and Barnetts. B. J. Barnett, who is believed to have emigrated from Estonia, arrived in South Carolina before the war, fought for the Confederate Army, and married Zelda Loryea of Charleston. Like many Eastern European immigrants, he peddled before becoming a storekeeper in Manville, a small town about 20 miles north of Sumter. He acquired hundreds of acres of land near his store for cotton farming. In 1880, accompanied by three of his grown children, Barnett moved to Sumter where they opened a general store.

Organized Jewish Life in Sumter

In 1874, the growing number of Sumter Jews organized the Hebrew Cemetery Society and bought land for a burial ground. Soon after, a second organization, the Hebrew Benevolent Society was founded and the two societies merged in 1881 under the Benevolent Society name. Another merger took place in 1895 between the Hebrew Benevolent Society and a third organization, the Sumter Society of Israelites, a congregation that appears to have formed in the early 1890s. The Sumter Society of Israelites, later known as Congregation Sinai, hired its first rabbi in 1904 and soon acquired its first synagogue, a wooden building that was replaced in 1912 when congregants built a brick synagogue, the home of Temple Sinai today. During the 1920s, the congregation affiliated with the Reform movement, though as the only congregation in Sumter, it accommodated Jews of different backgrounds and practices.

In 1874, the growing number of Sumter Jews organized the Hebrew Cemetery Society and bought land for a burial ground. Soon after, a second organization, the Hebrew Benevolent Society was founded and the two societies merged in 1881 under the Benevolent Society name. Another merger took place in 1895 between the Hebrew Benevolent Society and a third organization, the Sumter Society of Israelites, a congregation that appears to have formed in the early 1890s. The Sumter Society of Israelites, later known as Congregation Sinai, hired its first rabbi in 1904 and soon acquired its first synagogue, a wooden building that was replaced in 1912 when congregants built a brick synagogue, the home of Temple Sinai today. During the 1920s, the congregation affiliated with the Reform movement, though as the only congregation in Sumter, it accommodated Jews of different backgrounds and practices.

Moses Levi

Moses Levi

Jewish Businesses in Sumter

Sumter’s east-west rail lines, destroyed during the Civil War, became operational again in the early 1870s. The north-south connection took longer, but by the 1890s, Sumter was a transportation hub for a region reliant on agriculture and logging. Many of Sumter’s Jews were storeowners, such as general merchandisers J. Ryttenberg and Sons, Levi Brothers, and A. A. Solomons. The Ryttenberg family also owned Rose Hill Plantation and the Sumter Brickyard. H. Baruch sold groceries and dry goods, and Schwartz’s catered to female customers with general merchandise for women. Herman Schwerin of Charleston opened Schwerin and Company, selling grain and groceries. Beaufort-born J. E. Suares sold furniture and household items. The Bultman Brothers owned a shoe store, while H. Harby sold wagons, harnesses, and “first-class animals from Kentucky” out of his livery stable.

Between 1878 and 1905, the estimated Jewish population in Sumter grew from 89 to 175. Turn of the century downtown Sumter bustled with Jewish shop owners at the heart of the economic activity. Levy and Moses sold groceries and advertised health foods that would “banish medicines from the homes.” Cash’s Dry Goods was operated by Jacob Denemark and Harry Siegel, who later sold the business to Abe Mazursky. Mazursky, a Russian immigrant, had moved to Sumter from the nearby town of Mayesville and opened his department store, The Hub, in 1919. In the mid-1900s, it was renamed Berger’s for his daughter and son-in-law, his successors, who would streamline the shop to sell only men’s apparel. Schwartz’s, which also stayed open for decades under family ownership, evolved into a dress shop. Among their competitors were the Nesses, Benjamin and Esther, who moved to Sumter during the Depression and opened a ladies clothing store.

Besides shopkeeping, Jews worked in a variety of occupations. I. Strauss, proprietor of the Palace Saloon, sold spirits and “segars” in the late 19th century. In the first half of the 20th century, Marion Moïse, Edwin Warren’s son, was president of The Sumter Iron Works, and Davis D. Moïse and E. W. Moïse, Jr., ran the Machinery and Manufacturing Company. Henry P. Moses opened his own insurance company, another family-owned business kept operational for decades by subsequent generations. Wendell M. Levi and Harold Moïse opened the Palmetto Pigeon Plant in 1923. Levi had worked with pigeons while serving with the army’s signal corps during World War I. The business sold squabs, a venture that not only survived the Depression, but grew to become the largest squab farm in the country.

George D. Levy freelanced as a newspaper reporter while working to establish his law career. He was only one of a number of Jewish Sumter lawyers dating back to Franklin J. Moses, Sr. Several worked in the firm Lee and Moïse, established by Edwin Warren Moïse with a non-Jewish partner. They included two Marion Moïses, Edwin’s son and great-grandson, Issac C. Strauss, and Morris Mazursky, who left to start his own practice after the death of Strauss. Other Jewish lawyers practicing in Sumter in the 20th century included Wendell M. Levi, Harmon D. Moïse, and Mortimer M. Weinberg.

Sumter’s east-west rail lines, destroyed during the Civil War, became operational again in the early 1870s. The north-south connection took longer, but by the 1890s, Sumter was a transportation hub for a region reliant on agriculture and logging. Many of Sumter’s Jews were storeowners, such as general merchandisers J. Ryttenberg and Sons, Levi Brothers, and A. A. Solomons. The Ryttenberg family also owned Rose Hill Plantation and the Sumter Brickyard. H. Baruch sold groceries and dry goods, and Schwartz’s catered to female customers with general merchandise for women. Herman Schwerin of Charleston opened Schwerin and Company, selling grain and groceries. Beaufort-born J. E. Suares sold furniture and household items. The Bultman Brothers owned a shoe store, while H. Harby sold wagons, harnesses, and “first-class animals from Kentucky” out of his livery stable.

Between 1878 and 1905, the estimated Jewish population in Sumter grew from 89 to 175. Turn of the century downtown Sumter bustled with Jewish shop owners at the heart of the economic activity. Levy and Moses sold groceries and advertised health foods that would “banish medicines from the homes.” Cash’s Dry Goods was operated by Jacob Denemark and Harry Siegel, who later sold the business to Abe Mazursky. Mazursky, a Russian immigrant, had moved to Sumter from the nearby town of Mayesville and opened his department store, The Hub, in 1919. In the mid-1900s, it was renamed Berger’s for his daughter and son-in-law, his successors, who would streamline the shop to sell only men’s apparel. Schwartz’s, which also stayed open for decades under family ownership, evolved into a dress shop. Among their competitors were the Nesses, Benjamin and Esther, who moved to Sumter during the Depression and opened a ladies clothing store.

Besides shopkeeping, Jews worked in a variety of occupations. I. Strauss, proprietor of the Palace Saloon, sold spirits and “segars” in the late 19th century. In the first half of the 20th century, Marion Moïse, Edwin Warren’s son, was president of The Sumter Iron Works, and Davis D. Moïse and E. W. Moïse, Jr., ran the Machinery and Manufacturing Company. Henry P. Moses opened his own insurance company, another family-owned business kept operational for decades by subsequent generations. Wendell M. Levi and Harold Moïse opened the Palmetto Pigeon Plant in 1923. Levi had worked with pigeons while serving with the army’s signal corps during World War I. The business sold squabs, a venture that not only survived the Depression, but grew to become the largest squab farm in the country.

George D. Levy freelanced as a newspaper reporter while working to establish his law career. He was only one of a number of Jewish Sumter lawyers dating back to Franklin J. Moses, Sr. Several worked in the firm Lee and Moïse, established by Edwin Warren Moïse with a non-Jewish partner. They included two Marion Moïses, Edwin’s son and great-grandson, Issac C. Strauss, and Morris Mazursky, who left to start his own practice after the death of Strauss. Other Jewish lawyers practicing in Sumter in the 20th century included Wendell M. Levi, Harmon D. Moïse, and Mortimer M. Weinberg.

Civic Engagement

Sumter’s Jews devoted their time and energy to charities such as the Red Cross, the March of Dimes, the United Way, and the Salvation Army. They belonged to various clubs and organizations including the Kiwanis Club, the American Legion, the Chamber of Commerce, the Sumter Garden Club, the Jaycees, the Rotary Club, the Shriners, the Masons, the Elks, the Sumter County Historical Society, and the local country club.

Jews also made their mark in government service. Davis DeLeon Moïse, who served in the South Carolina House and Senate, was a member of the committee that proposed a council-manager government for Sumter. The change was implemented in 1912 after approval by the legislature and the voters, making Sumter one of the first cities in the country to adopt the new plan. Beginning in 1958, Morris Mazursky served seven terms as a Sumter city councilman. B. J. Barnett also served on city council, and Richard Moses was elected mayor for one term. Julien Weinberg of Manning served two terms on that city’s council and two terms as its mayor. He also served as a probate judge for Clarendon County. Sumter Jews reportedly experienced no significant anti-Semitism. Indeed, interfaith dialogue and intermarriage were commonplace.

Sumter’s Jews devoted their time and energy to charities such as the Red Cross, the March of Dimes, the United Way, and the Salvation Army. They belonged to various clubs and organizations including the Kiwanis Club, the American Legion, the Chamber of Commerce, the Sumter Garden Club, the Jaycees, the Rotary Club, the Shriners, the Masons, the Elks, the Sumter County Historical Society, and the local country club.

Jews also made their mark in government service. Davis DeLeon Moïse, who served in the South Carolina House and Senate, was a member of the committee that proposed a council-manager government for Sumter. The change was implemented in 1912 after approval by the legislature and the voters, making Sumter one of the first cities in the country to adopt the new plan. Beginning in 1958, Morris Mazursky served seven terms as a Sumter city councilman. B. J. Barnett also served on city council, and Richard Moses was elected mayor for one term. Julien Weinberg of Manning served two terms on that city’s council and two terms as its mayor. He also served as a probate judge for Clarendon County. Sumter Jews reportedly experienced no significant anti-Semitism. Indeed, interfaith dialogue and intermarriage were commonplace.

The Jewish Community in Sumter Today

Temple Sinai's brick synagogue was built in 1912

Temple Sinai's brick synagogue was built in 1912

After World War II, the Jewish community of Sumter grew, reaching a peak of 390 people by 1960. Over the past several decades, however, numbers have declined as Jews have left Sumter for economic and professional opportunities in larger cities. By 1980, only 190 Jews lived in Sumter; today, Temple Sinai has only 40 members and they have begun to discuss the eventual closing of their synagogue. In 2007, the congregation donated its treasured archives to the Jewish Heritage Collection at the College of Charleston to assure the preservation and accessibility of its historic contents. Sumter’s small Jewish community has left an important legacy not only in the city, but across the state.