Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Temple Sinai - Sumter, South Carolina

All photos courtesy of Special Collections, College of Charleston

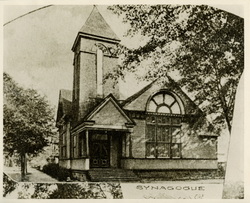

Temple Sinai's first synagogue

Temple Sinai's first synagogue

The first sign of a Jewish organization in Sumter appeared in 1874 with the purchase of land for a cemetery by the Sumter Hebrew Cemetery Society. Some time later, another group founded the Sumter Hebrew Benevolent Society, which merged with the Hebrew Cemetery Society in 1881 under the Benevolent Society name. In 1895, the Benevolent Society merged once again, this time with the Sumter Society of Israelites, which had been formed in 1887. The Sumter Society of Israelites, later known as Congregation Sinai, has served Sumter’s Jewish community ever since.

The Sumter Hebrew Benevolent Society held its meetings in the Masonic Hall above J. Ryttenberg and Sons on the corner of Main and Liberty Streets. At the same May 1881 meeting where the two societies agreed to merge, members moved quickly to elect officers, formalize a constitution, and start a Sunday school. By the end of the year however, the organizers appeared to lose some of their momentum. Attendance may have been sporadic since they agreed to reduce the monthly meetings to quarterly. By May 1882, initial plans to hold informative lectures and establish a library with a reading room fell through. In February of that year, a Reverend Mr. Levy had spoken to the group about the plight of Russian refugees and the society collected $160 in aid. They also formed a Russian Aid Committee to help the new arrivals find jobs. By September they were supporting two men until jobs came available in the fruit business. Committee members agreed to notify Baltimore and Charleston that they could not accommodate any more refugees in Sumter. In 1889, there were fewer than 20 members in the Society.

The Sunday school appears to have been one of the members’ primary concerns. Organized shortly after the Benevolent Society’s first recorded meeting in April 1881, the Sunday school had 24 students in 1883. By 1889 or so, Rabbi David Levy of Charleston’s Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim was traveling to Sumter to teach the confirmation class. His Sumter students, in turn, traveled to Charleston to participate in Beth Elohim’s confirmation ceremonies. Miss Carrie Moses became the superintendent in 1891 and held the position for a number of years. Visiting Rabbis E. S. Levy of Augusta, Georgia, and David Levy of Charleston provided their services periodically. Lay readers led services when they were not available.

In 1895, the Hebrew Benevolent Society merged into the Sumter Society of Israelites, but, the society became inactive around the turn of the century. In 1904, it reorganized with a boost from a growing Jewish community, resulting in a new name, Congregation Sinai, and its first full-time rabbi, Jacob Klein. By 1905, the congregation had acquired a synagogue, Temple Sinai. The first temple was a wooden building located on the corner of Hampton and Church Streets. By 1907, the congregation had 40 members, ten students in the religious school, and an annual income of $1500. The Jewish Ladies’ Aid Society had 45 members.

Rabbi Jacob Klein served four years before resigning. He was followed by Rabbi David Sessler, whose contract was not renewed after two years of service. Rabbi David Klein led the congregation from 1910 to 1917. He presided over the Sinai Culture Society, organized in October 1910, which was designed “to promote the social, intellectual and religious life of its members.” All Congregation Sinai members were eligible, and the first meeting’s roll lists nine women and 15 men. By the summer of 1911, the group had disbanded.

After David Klein left in 1917, two years passed before the congregation found another rabbi. In 1919, they hired Ferdinand K. Hirsch, whose contract they renewed on a yearly basis. Besides attending to rabbinical duties in Sumter and neighboring towns such as Camden, Hirsch ran the religious school, managed the cemetery, and handled charitable distributions. Much to the congregation’s regret, he left in 1928. Rabbi Hirsch L. Freund succeeded him, serving only two years before resigning.

The Sumter Hebrew Benevolent Society held its meetings in the Masonic Hall above J. Ryttenberg and Sons on the corner of Main and Liberty Streets. At the same May 1881 meeting where the two societies agreed to merge, members moved quickly to elect officers, formalize a constitution, and start a Sunday school. By the end of the year however, the organizers appeared to lose some of their momentum. Attendance may have been sporadic since they agreed to reduce the monthly meetings to quarterly. By May 1882, initial plans to hold informative lectures and establish a library with a reading room fell through. In February of that year, a Reverend Mr. Levy had spoken to the group about the plight of Russian refugees and the society collected $160 in aid. They also formed a Russian Aid Committee to help the new arrivals find jobs. By September they were supporting two men until jobs came available in the fruit business. Committee members agreed to notify Baltimore and Charleston that they could not accommodate any more refugees in Sumter. In 1889, there were fewer than 20 members in the Society.

The Sunday school appears to have been one of the members’ primary concerns. Organized shortly after the Benevolent Society’s first recorded meeting in April 1881, the Sunday school had 24 students in 1883. By 1889 or so, Rabbi David Levy of Charleston’s Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim was traveling to Sumter to teach the confirmation class. His Sumter students, in turn, traveled to Charleston to participate in Beth Elohim’s confirmation ceremonies. Miss Carrie Moses became the superintendent in 1891 and held the position for a number of years. Visiting Rabbis E. S. Levy of Augusta, Georgia, and David Levy of Charleston provided their services periodically. Lay readers led services when they were not available.

In 1895, the Hebrew Benevolent Society merged into the Sumter Society of Israelites, but, the society became inactive around the turn of the century. In 1904, it reorganized with a boost from a growing Jewish community, resulting in a new name, Congregation Sinai, and its first full-time rabbi, Jacob Klein. By 1905, the congregation had acquired a synagogue, Temple Sinai. The first temple was a wooden building located on the corner of Hampton and Church Streets. By 1907, the congregation had 40 members, ten students in the religious school, and an annual income of $1500. The Jewish Ladies’ Aid Society had 45 members.

Rabbi Jacob Klein served four years before resigning. He was followed by Rabbi David Sessler, whose contract was not renewed after two years of service. Rabbi David Klein led the congregation from 1910 to 1917. He presided over the Sinai Culture Society, organized in October 1910, which was designed “to promote the social, intellectual and religious life of its members.” All Congregation Sinai members were eligible, and the first meeting’s roll lists nine women and 15 men. By the summer of 1911, the group had disbanded.

After David Klein left in 1917, two years passed before the congregation found another rabbi. In 1919, they hired Ferdinand K. Hirsch, whose contract they renewed on a yearly basis. Besides attending to rabbinical duties in Sumter and neighboring towns such as Camden, Hirsch ran the religious school, managed the cemetery, and handled charitable distributions. Much to the congregation’s regret, he left in 1928. Rabbi Hirsch L. Freund succeeded him, serving only two years before resigning.

In March 1913, the congregation dedicated a new brick temple, replacing the wooden one which members believe was destroyed in a fire. Temple Sinai’s architecture, combined with the congregation’s historical and religious significance, earned the building a listing on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999. Its Moorish features, including domed roofs, are complemented by eleven stained glass windows. The small, circular eleventh window above the door, a gift of Mr. and Mrs. Milton Schlessinger, was manufactured by the Empire Glass Company of Atlanta, Georgia, and installed in the 1950s.

Religious practices among Sumter’s Jews in the first half of the 20th century varied. Some mothers greeted the Sabbath with the lighting of candles, whereas others observed religious traditions on the holidays only. There were a number of mixed marriages, resulting in the observance of both Jewish and Christian holidays. Those raised in the Orthodox tradition found that keeping their own kitchens kosher proved impractical in a town without a kosher butcher. Although the recent immigrants from Eastern Europe adapted to the Reform Judaism imported from Charleston, Sumterites growing up between the world wars recall a subtle divide between the early settlers of Sephardic and German descent and the newer arrivals. One member recalls a time when the two groups sat on opposite sides of the synagogue. By 1925, the congregation had joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the national organization of Reform Judaism.

The Sunday school continued to be a primary concern throughout the 20th century. In 1927, the annual meeting minutes report that the school was in “good condition” with more than 30 children from Sumter and Manning attending. Plans to recruit students from Bishopville in 1932 may have been successful as the enrollment increased to approximately 40 that year with five teachers volunteering their services.

During the interwar years, participation by members in weekly services and other temple activities declined, despite a recorded membership of 100 families in 1926. At the 1928 annual meeting, President Herbert A. Moses spoke of the “urgent” matter of the congregation’s “continued existence.” In a long speech, he bemoaned members’ tendency to choose other activities over the spiritual benefits offered by the Society of Israelites. Moses proclaimed, “if ever an association of persons was permeated with a marked degree of indifference toward all its functions, that to my mind is the condition of our congregation today.” Moses pointed to a problem that would be a recurring theme throughout much of the congregation’s history.

Samuel R. Shillman of Chattanooga, Tennessee, became Congregation Sinai’s new rabbi in 1930. His longevity—Shillman stayed until 1948—suggests members were satisfied with his work. In 1942, Shillman encouraged them to attend the cornerstone-laying ceremonies for a new synagogue in Dillon, a town about 70 miles northeast of Sumter. Three years prior, Jews from Dillon and several surrounding towns had asked Shillman to help them organize a congregation. For three years, with Temple Sinai’s blessing, Shillman had traveled to Dillon once a month to serve the Ohav Shalom Congregation. Shillman was busy with other activities outside the congregation as well. Acting as a goodwill ambassador from the Jewish community, he lectured at conferences throughout the Southeast and spoke to South Carolina communities on a variety of issues.

In 1935, when the estimated Jewish population of Sumter had exceeded 200, membership totaled about 90 families. The establishment of Shaw Air Field in 1941 also helped to boost Congregation Sinai’s membership over the years. The training base for Army Air Corps pilots was located just northwest of Sumter and employed approximately 5000 military and civilian workers by 1942. Renamed Shaw Air Force Base in 1948, its Jewish military personnel were welcomed into every facet of Temple Sinai’s community. As many as a dozen Jewish families from surrounding small towns such as Manning, Bishopville, Greeleyville, Mayesville, Hartsville, Kingstree, Summerton, and Denmark were members as well. Over much of the 20th century, membership fluctuated between 70 and 90 families, until the mid-to-late 1980s when it fell below 60.

Religious practices among Sumter’s Jews in the first half of the 20th century varied. Some mothers greeted the Sabbath with the lighting of candles, whereas others observed religious traditions on the holidays only. There were a number of mixed marriages, resulting in the observance of both Jewish and Christian holidays. Those raised in the Orthodox tradition found that keeping their own kitchens kosher proved impractical in a town without a kosher butcher. Although the recent immigrants from Eastern Europe adapted to the Reform Judaism imported from Charleston, Sumterites growing up between the world wars recall a subtle divide between the early settlers of Sephardic and German descent and the newer arrivals. One member recalls a time when the two groups sat on opposite sides of the synagogue. By 1925, the congregation had joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the national organization of Reform Judaism.

The Sunday school continued to be a primary concern throughout the 20th century. In 1927, the annual meeting minutes report that the school was in “good condition” with more than 30 children from Sumter and Manning attending. Plans to recruit students from Bishopville in 1932 may have been successful as the enrollment increased to approximately 40 that year with five teachers volunteering their services.

During the interwar years, participation by members in weekly services and other temple activities declined, despite a recorded membership of 100 families in 1926. At the 1928 annual meeting, President Herbert A. Moses spoke of the “urgent” matter of the congregation’s “continued existence.” In a long speech, he bemoaned members’ tendency to choose other activities over the spiritual benefits offered by the Society of Israelites. Moses proclaimed, “if ever an association of persons was permeated with a marked degree of indifference toward all its functions, that to my mind is the condition of our congregation today.” Moses pointed to a problem that would be a recurring theme throughout much of the congregation’s history.

Samuel R. Shillman of Chattanooga, Tennessee, became Congregation Sinai’s new rabbi in 1930. His longevity—Shillman stayed until 1948—suggests members were satisfied with his work. In 1942, Shillman encouraged them to attend the cornerstone-laying ceremonies for a new synagogue in Dillon, a town about 70 miles northeast of Sumter. Three years prior, Jews from Dillon and several surrounding towns had asked Shillman to help them organize a congregation. For three years, with Temple Sinai’s blessing, Shillman had traveled to Dillon once a month to serve the Ohav Shalom Congregation. Shillman was busy with other activities outside the congregation as well. Acting as a goodwill ambassador from the Jewish community, he lectured at conferences throughout the Southeast and spoke to South Carolina communities on a variety of issues.

In 1935, when the estimated Jewish population of Sumter had exceeded 200, membership totaled about 90 families. The establishment of Shaw Air Field in 1941 also helped to boost Congregation Sinai’s membership over the years. The training base for Army Air Corps pilots was located just northwest of Sumter and employed approximately 5000 military and civilian workers by 1942. Renamed Shaw Air Force Base in 1948, its Jewish military personnel were welcomed into every facet of Temple Sinai’s community. As many as a dozen Jewish families from surrounding small towns such as Manning, Bishopville, Greeleyville, Mayesville, Hartsville, Kingstree, Summerton, and Denmark were members as well. Over much of the 20th century, membership fluctuated between 70 and 90 families, until the mid-to-late 1980s when it fell below 60.

Rabbi J. Aaron Levy succeeded Shillman in 1949. Levy and the congregation must have decided early on that their match was a good one. Although he was offered a job in 1956 with another congregation for more money than he was making in Sumter, Levy renewed with Congregation Sinai. He began to introduce some traditional practices to the Reform congregation, including its first bar mitzvah ceremony in 1964. Levy continued the tradition of serving Jews living in the surrounding small towns, particularly Camden and Darlington. Throughout his term of service to Temple Sinai, he acted as the chaplain at Shaw Air Force Base. In the late 1960s, he also acted as auxiliary chaplain at Myrtle Beach Air Force Base. Levy was involved in the Sumter community as well, serving on the boards of numerous civic organizations. He stayed with Congregation Sinai until his retirement in 1970.

Congregation Sinai next relied on a student rabbi from Hebrew Union College, Edward Ruttenberg, who tried to introduce more traditional elements to the worship service. Ruttenberg wore a yarmulke and used more Hebrew in his services than members were accustomed to hearing. He also recommended that Sunday school students learn Hebrew, arguing that the language united all Jews. The board resisted this entreaty, though by 1976, Hebrew became part of the Sunday school curriculum.

Rabbi Avshalom Magidovitch arrived at Temple Sinai in 1973, and continued to push the congregation away from classical Reform practice. At his first annual meeting, Magidovitch pointed to several problem areas, including “uninvolvement,” the “need for education at several levels,” and a “diversity of opinions bordering on division.” He recommended incorporating more traditional rituals, oneg receptions after services, and adult education. He also called for changes to the Sunday school curriculum. While the sisterhood began offering onegs, it is unclear how Magidovitch’s other ideas were received. Nonetheless, members felt “respect, admiration, and love” for the rabbi who continued to serve Congregation Sinai and the neighboring communities until he became ill and died in 1979. His widow, Revelle Magidovitch, remained in Sumter until the late 1990s, and was an active member of the congregation and the Sumter community. Besides serving as president of the sisterhood, Revelle taught adult bat mitzvah classes to other sisterhood members.

The members of Congregation Sinai were remarkably successful in the years after World War II in building an organization that fulfilled their spiritual needs and provided a sense of community. Holidays, of course, drew the largest crowds. Besides High Holy Days services, the congregation held a community Seder, and the Sunday school hosted Hanukkah and Purim parties. The Men’s Club collected contributions for the Jewish Welfare Fund and thousands of dollars in members’ donations were sent to the United Jewish Appeal and several other Jewish charities.

Over the years, the congregation expanded its facilities. In 1932, it completed a new adjoining community center, the Barnett Memorial Building, which included an assembly room with a stage and a kitchen. In 1956, the Hyman Brody Educational Building was constructed to accommodate the growing religious school.

The women of Temple Sinai’s Sisterhood, originally the Ladies Aid Society, exhibited an astonishing amount of energy and devotion in their mission to support the congregation and community. There was no area of temple life in which they did not play a role, lending assistance wherever and whenever it was needed. They held annual bulb and rummage sales to raise funds for repairs, renovations, and special projects. They provided refreshments after services and meals at the annual meetings, threw holiday parties, decorated the sanctuary for services, supervised the upkeep and appearance of the temple, and for a time, financially supported the choir. They were prominent and active members of the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods and were no less devoted to supporting the needy of the greater Sumter community. One of their flagship programs helped blind children to make the transition from institutions to public schools by providing books they had translated into Braille.

Congregation Sinai next relied on a student rabbi from Hebrew Union College, Edward Ruttenberg, who tried to introduce more traditional elements to the worship service. Ruttenberg wore a yarmulke and used more Hebrew in his services than members were accustomed to hearing. He also recommended that Sunday school students learn Hebrew, arguing that the language united all Jews. The board resisted this entreaty, though by 1976, Hebrew became part of the Sunday school curriculum.

Rabbi Avshalom Magidovitch arrived at Temple Sinai in 1973, and continued to push the congregation away from classical Reform practice. At his first annual meeting, Magidovitch pointed to several problem areas, including “uninvolvement,” the “need for education at several levels,” and a “diversity of opinions bordering on division.” He recommended incorporating more traditional rituals, oneg receptions after services, and adult education. He also called for changes to the Sunday school curriculum. While the sisterhood began offering onegs, it is unclear how Magidovitch’s other ideas were received. Nonetheless, members felt “respect, admiration, and love” for the rabbi who continued to serve Congregation Sinai and the neighboring communities until he became ill and died in 1979. His widow, Revelle Magidovitch, remained in Sumter until the late 1990s, and was an active member of the congregation and the Sumter community. Besides serving as president of the sisterhood, Revelle taught adult bat mitzvah classes to other sisterhood members.

The members of Congregation Sinai were remarkably successful in the years after World War II in building an organization that fulfilled their spiritual needs and provided a sense of community. Holidays, of course, drew the largest crowds. Besides High Holy Days services, the congregation held a community Seder, and the Sunday school hosted Hanukkah and Purim parties. The Men’s Club collected contributions for the Jewish Welfare Fund and thousands of dollars in members’ donations were sent to the United Jewish Appeal and several other Jewish charities.

Over the years, the congregation expanded its facilities. In 1932, it completed a new adjoining community center, the Barnett Memorial Building, which included an assembly room with a stage and a kitchen. In 1956, the Hyman Brody Educational Building was constructed to accommodate the growing religious school.

The women of Temple Sinai’s Sisterhood, originally the Ladies Aid Society, exhibited an astonishing amount of energy and devotion in their mission to support the congregation and community. There was no area of temple life in which they did not play a role, lending assistance wherever and whenever it was needed. They held annual bulb and rummage sales to raise funds for repairs, renovations, and special projects. They provided refreshments after services and meals at the annual meetings, threw holiday parties, decorated the sanctuary for services, supervised the upkeep and appearance of the temple, and for a time, financially supported the choir. They were prominent and active members of the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods and were no less devoted to supporting the needy of the greater Sumter community. One of their flagship programs helped blind children to make the transition from institutions to public schools by providing books they had translated into Braille.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the religious school taught between 40 and 60 students each year, including those from Camden, Bishopville, and Shaw Air Force Base. Enrollment rose suddenly in the mid-1960s, peaking at 80 in 1968 with the baby boomers coming of age. By 1971, enrollment had plummeted to 36. Reflecting the shrinking and graying congregation, by 1989 the Sunday school had become inactive forcing Sumter’s remaining Jewish children to travel to Columbia or Florence for religious instruction.

A temple youth group, founded in 1954, boasted 20 members by 1966, including five from Kingstree, two from Camden, and one from Bishopville. At the 1973 annual meeting, the youth group president reported that the organization was experiencing its most active year due to a high level of interest and involvement. The youth group, he added, has “measured up in strength, unity, and manpower to larger groups.” After 1973, organizers note a sudden and dramatic change in its vitality. The theme of the 1975 retreat was apathy among members. The group vacillated for a few years between inactivity and the struggle of a few to raise funds and complete service projects. In 1986, it was declared defunct and Florence’s congregation, Beth Israel, invited Congregation Sinai teenagers to join their youth organization. Just as the Sunday school attendance had peaked and declined in the late 1960s as the baby boomers departed, youth group members followed the same pattern as they graduated from high school and left Sumter for college.

In 1980, the board hired Milton Schlager as their rabbi. By January 1981, Rabbi Schlager was appealing to young couples for greater participation in congregation life. He tried to keep members’ interest by introducing new rituals and varying his services and sermons. Despite these efforts, participation waned as membership declined. In 1989, the board decided not to renew Rabbi Schlager’s contract, questioning the necessity of a rabbi when so few attended Friday services. Some felt, however, that a new spiritual leader might reinvigorate the weakened congregation. By 1990, the board had come to accept Congregation Sinai’s future limitations and began to discuss a trust agreement in the event they were unable to continue as a congregation.

Despite these concerns about the future, Congregation Sinai, numbering 60 members, hired Rabbi Richard Leviton in 1991. The Sunday school resumed with six young children enrolled, although a few children continued to attend Columbia’s Tree of Life Sunday school. Leviton held a monthly study group and served Shaw Air Force Base and Wateree Correctional Institute. He left in 1996 when his contract expired and the congregation was unable to afford his full-time salary. For the next few years, members relied on a series of student rabbis from Hebrew Union College.

Rabbi Robert A. Seigel has served the congregation on a part-time basis since 2001. Congregation Sinai still holds weekly Friday night services; the rabbi conducts two services a month and two lay readers lead in his absence. Typically, ten to 15 people attend the lay services, while 15 to 20 attend the rabbi-led services. The rabbi also conducts regular adult courses for the members. In previous years, he held an adult education class for the general public, which was well attended by non-Jewish residents of the area. There is no Sunday school. The few children in the congregation go to Columbia for their religious education. The sisterhood is still active and continues to be the “backbone” of the congregation.

Currently, Congregation Sinai has about 40 members, most of whom are senior citizens. Attempts to attract new and younger members who can carry on the legacy of Jewish religious tradition in Sumter have not been successful. Sumter itself has been growing, with new businesses, a shopping mall, and subdivisions springing up. While younger, well-off Jewish families live in Sumter, they are not interested in congregational activities, although many will attend one service during the High Holy Days. Members believe the high rate of intermarriage, which has been the norm in Sumter throughout its history, is largely responsible for the difficulties associated with membership and participation. They expect the demise of the congregation will occur in the next decade or so. In anticipation of that day, they have begun long-range planning to assure that cemetery and temple affairs will be managed appropriately.

A temple youth group, founded in 1954, boasted 20 members by 1966, including five from Kingstree, two from Camden, and one from Bishopville. At the 1973 annual meeting, the youth group president reported that the organization was experiencing its most active year due to a high level of interest and involvement. The youth group, he added, has “measured up in strength, unity, and manpower to larger groups.” After 1973, organizers note a sudden and dramatic change in its vitality. The theme of the 1975 retreat was apathy among members. The group vacillated for a few years between inactivity and the struggle of a few to raise funds and complete service projects. In 1986, it was declared defunct and Florence’s congregation, Beth Israel, invited Congregation Sinai teenagers to join their youth organization. Just as the Sunday school attendance had peaked and declined in the late 1960s as the baby boomers departed, youth group members followed the same pattern as they graduated from high school and left Sumter for college.

In 1980, the board hired Milton Schlager as their rabbi. By January 1981, Rabbi Schlager was appealing to young couples for greater participation in congregation life. He tried to keep members’ interest by introducing new rituals and varying his services and sermons. Despite these efforts, participation waned as membership declined. In 1989, the board decided not to renew Rabbi Schlager’s contract, questioning the necessity of a rabbi when so few attended Friday services. Some felt, however, that a new spiritual leader might reinvigorate the weakened congregation. By 1990, the board had come to accept Congregation Sinai’s future limitations and began to discuss a trust agreement in the event they were unable to continue as a congregation.

Despite these concerns about the future, Congregation Sinai, numbering 60 members, hired Rabbi Richard Leviton in 1991. The Sunday school resumed with six young children enrolled, although a few children continued to attend Columbia’s Tree of Life Sunday school. Leviton held a monthly study group and served Shaw Air Force Base and Wateree Correctional Institute. He left in 1996 when his contract expired and the congregation was unable to afford his full-time salary. For the next few years, members relied on a series of student rabbis from Hebrew Union College.

Rabbi Robert A. Seigel has served the congregation on a part-time basis since 2001. Congregation Sinai still holds weekly Friday night services; the rabbi conducts two services a month and two lay readers lead in his absence. Typically, ten to 15 people attend the lay services, while 15 to 20 attend the rabbi-led services. The rabbi also conducts regular adult courses for the members. In previous years, he held an adult education class for the general public, which was well attended by non-Jewish residents of the area. There is no Sunday school. The few children in the congregation go to Columbia for their religious education. The sisterhood is still active and continues to be the “backbone” of the congregation.

Currently, Congregation Sinai has about 40 members, most of whom are senior citizens. Attempts to attract new and younger members who can carry on the legacy of Jewish religious tradition in Sumter have not been successful. Sumter itself has been growing, with new businesses, a shopping mall, and subdivisions springing up. While younger, well-off Jewish families live in Sumter, they are not interested in congregational activities, although many will attend one service during the High Holy Days. Members believe the high rate of intermarriage, which has been the norm in Sumter throughout its history, is largely responsible for the difficulties associated with membership and participation. They expect the demise of the congregation will occur in the next decade or so. In anticipation of that day, they have begun long-range planning to assure that cemetery and temple affairs will be managed appropriately.