Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Orthodox Congregations, Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis’s Jewish community has among the largest Orthodox population per capita of any southern city. In most other cities, many Orthodox congregations founded over a century ago have long since closed or moved away from traditional Judaism. In 1941, Memphis had four congregations that belonged to the Union of Orthodox Congregations of America. Today, Memphis has managed to maintain two significantly sized Orthodox synagogues, including one that boasts of being the largest Orthodox congregation in the United States.

The history of Memphis’ Orthodox Jewish community is rooted in the “Pinch,” the downtown neighborhood that began to fill with Jewish immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Once Memphis Jews began to move out of the old neighborhood to the eastern part of the city, these Orthodox congregations either had to follow or disband. Orthodox Jews need to be within walking distance of their synagogue in order to adhere to traditional strictures against driving or riding on the Sabbath. Some Orthodox shuls were able to make the transition to the suburbs, while others weren’t. The story of Orthodoxy in Memphis is the chronicle of this movement from the immigrant enclave of the Pinch to the growing post-war suburbs.

The first congregation founded in Memphis, B’nai Israel, which was chartered in 1854, adhered to traditional Judaism, though it soon began to adopt the ritual changes associated with Reform Judaism. In 1861, a group disgruntled with these changes broke away and established Beth El Emeth (House of the God of Truth). The following year, they received an official charter and acquired a synagogue. Dedicated to preserving Orthodox practice, Beth El Emeth hired Rabbi Jacob Peres, who had been the first rabbi at B’nai Israel. In 1872, they hired Rabbi Ferdinand Leopold Sarner, who made history during the Civil War as the first Jewish chaplain to serve in the US military. Beth El Emeth did not survive Memphis’ Yellow Fever epidemic of 1878. Due to deaths and evacuations, the congregation lost much of its membership and decided to rejoin B’nai Israel. A group unhappy with this decision chose to pray together informally in rented halls rather than join the Reform congregation. Thirty-eight years later, Beth El Emeth would be reorganized.

A group of Jewish immigrants who wished to follow religious Orthodoxy began to pray together by 1884 in rooms above various stores. In 1892, the group was chartered as the Baron Hirsch Benevolent Society, named in honor of the famed French Jewish philanthropist. That same year they purchased a former African American church at 4th Street and Washington Avenue for use as a synagogue. Rabbi I. Myerowitz was its first spiritual leader, serving from 1891 to 1893. Soon after they bought their building, the congregation opened a Talmud Torah, though it only lasted a few years. Soon after, a group of women from B’nai Israel organized and ran a Sunday school for the children of Baron Hirsch, feeling strongly that these children of immigrants needed religious instruction. By 1907, Baron Hirsch had 110 members and 45 children in its religious school.

The history of Memphis’ Orthodox Jewish community is rooted in the “Pinch,” the downtown neighborhood that began to fill with Jewish immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Once Memphis Jews began to move out of the old neighborhood to the eastern part of the city, these Orthodox congregations either had to follow or disband. Orthodox Jews need to be within walking distance of their synagogue in order to adhere to traditional strictures against driving or riding on the Sabbath. Some Orthodox shuls were able to make the transition to the suburbs, while others weren’t. The story of Orthodoxy in Memphis is the chronicle of this movement from the immigrant enclave of the Pinch to the growing post-war suburbs.

The first congregation founded in Memphis, B’nai Israel, which was chartered in 1854, adhered to traditional Judaism, though it soon began to adopt the ritual changes associated with Reform Judaism. In 1861, a group disgruntled with these changes broke away and established Beth El Emeth (House of the God of Truth). The following year, they received an official charter and acquired a synagogue. Dedicated to preserving Orthodox practice, Beth El Emeth hired Rabbi Jacob Peres, who had been the first rabbi at B’nai Israel. In 1872, they hired Rabbi Ferdinand Leopold Sarner, who made history during the Civil War as the first Jewish chaplain to serve in the US military. Beth El Emeth did not survive Memphis’ Yellow Fever epidemic of 1878. Due to deaths and evacuations, the congregation lost much of its membership and decided to rejoin B’nai Israel. A group unhappy with this decision chose to pray together informally in rented halls rather than join the Reform congregation. Thirty-eight years later, Beth El Emeth would be reorganized.

A group of Jewish immigrants who wished to follow religious Orthodoxy began to pray together by 1884 in rooms above various stores. In 1892, the group was chartered as the Baron Hirsch Benevolent Society, named in honor of the famed French Jewish philanthropist. That same year they purchased a former African American church at 4th Street and Washington Avenue for use as a synagogue. Rabbi I. Myerowitz was its first spiritual leader, serving from 1891 to 1893. Soon after they bought their building, the congregation opened a Talmud Torah, though it only lasted a few years. Soon after, a group of women from B’nai Israel organized and ran a Sunday school for the children of Baron Hirsch, feeling strongly that these children of immigrants needed religious instruction. By 1907, Baron Hirsch had 110 members and 45 children in its religious school.

Baron Hirsch continued to grow and soon tore down their old building and built a new synagogue on the same site in 1915. At a cost of $35,000, the new synagogue could hold over 700 worshippers in its sanctuary. In 1928, the congregation built the Menorah Institute next to the synagogue, which provided classrooms for a daily Talmud Torah and Sunday school, as well as plenty of space for congregation social activities. During World War II, Baron Hirsch opened the Menorah Institute up to soldiers stationed in the area, converting part of the building to a USO Center with sleeping quarters. Baron Hirsch paved the outside area between the synagogue and the Menorah Institute so it could be used for USO dances.

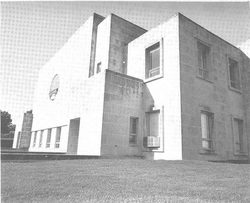

While the congregation struggled somewhat during the Great Depression, it flourished after World War II. In 1941, Baron Hirsch had 500 member households and 300 children in its religious school. By the late 1950s, it had over 1000 households and 500 children in its school. Rabbi Isadore Goodman led the congregation during this period of tremendous growth. With this dramatic increase in membership, and the movement of Jews out of the Pinch, Baron Hirsch began to plan for a new synagogue. With prominent real estate mogul Philip Belz as the head of the building committee, Baron Hirsch completed its enormous new synagogue in 1957. Its sanctuary had 2200 permanent seats and could accommodate an additional 1000 worshippers. This grand synagogue was a testament to the continued strength of Orthodox Judaism in Memphis and the deep pockets of many Baron Hirsch members.

As an Orthodox synagogue, Baron Hirsch needed to remain within walking distance of most of its members, who were continuing to move eastward toward the Memphis suburbs. The congregation bought the estate of soul music legend Isaac Hayes for use as a satellite campus, and soon realized that the entire synagogue complex would have to move as well. After buying additional land next to the satellite site, Baron Hirsch underwent another building campaign, completing their impressive new synagogue on South Yates Road in 1988. This time, Jack Belz, who had taken over his father Philip’s business, was chairman of the building committee. Though it has shrunk a bit from its post-war peak, Baron Hirsch still claims to be the largest Orthodox congregation in the country.

Baron Hirsch was the great success story of the Pinch’s Orthodox synagogues, others were unable to survive the demise of Memphis’ Jewish immigrant neighborhood. In 1900, ten men, led by Judah Friedman, broke away from Baron Hirsch and founded Anshei Mischne (People of the Book). For their first few years, the group met in a rented house; by 1903, they had moved into a brick building on Jackson Avenue. By 1907, they had purchased the building, though they tore it down twenty years later to build a new synagogue on the same site. Their new synagogue seated 250 people in its sanctuary and also had a mikvah. Ignatz Isaac was Anshei Mischne’s first rabbi, and served the congregation for most its existence. M.D. Blockman served as the congregation’s president for over thirty years. Although Anshei Mischne had 175 members in 1941, the congregation eventually disbanded after most of them moved out of the Pinch to the eastern part of Memphis.

In 1912, 25 Jews from Galicia formed their own congregation, the appropriately named Anshei Galicia (People of Galicia), so they could worship in their preferred style. They acquired a two-story brick synagogue on Jackson Avenue and 2nd Street in the Pinch. With a grocery store on the ground floor and a small sanctuary with seating for fifty worshippers on the second floor, Anshei Galicia paled in comparison to most of the other synagogues in the city. It had never had a full-time rabbi as members always led services. By 1941, the congregation only had sixteen members and soon became defunct.

While the congregation struggled somewhat during the Great Depression, it flourished after World War II. In 1941, Baron Hirsch had 500 member households and 300 children in its religious school. By the late 1950s, it had over 1000 households and 500 children in its school. Rabbi Isadore Goodman led the congregation during this period of tremendous growth. With this dramatic increase in membership, and the movement of Jews out of the Pinch, Baron Hirsch began to plan for a new synagogue. With prominent real estate mogul Philip Belz as the head of the building committee, Baron Hirsch completed its enormous new synagogue in 1957. Its sanctuary had 2200 permanent seats and could accommodate an additional 1000 worshippers. This grand synagogue was a testament to the continued strength of Orthodox Judaism in Memphis and the deep pockets of many Baron Hirsch members.

As an Orthodox synagogue, Baron Hirsch needed to remain within walking distance of most of its members, who were continuing to move eastward toward the Memphis suburbs. The congregation bought the estate of soul music legend Isaac Hayes for use as a satellite campus, and soon realized that the entire synagogue complex would have to move as well. After buying additional land next to the satellite site, Baron Hirsch underwent another building campaign, completing their impressive new synagogue on South Yates Road in 1988. This time, Jack Belz, who had taken over his father Philip’s business, was chairman of the building committee. Though it has shrunk a bit from its post-war peak, Baron Hirsch still claims to be the largest Orthodox congregation in the country.

Baron Hirsch was the great success story of the Pinch’s Orthodox synagogues, others were unable to survive the demise of Memphis’ Jewish immigrant neighborhood. In 1900, ten men, led by Judah Friedman, broke away from Baron Hirsch and founded Anshei Mischne (People of the Book). For their first few years, the group met in a rented house; by 1903, they had moved into a brick building on Jackson Avenue. By 1907, they had purchased the building, though they tore it down twenty years later to build a new synagogue on the same site. Their new synagogue seated 250 people in its sanctuary and also had a mikvah. Ignatz Isaac was Anshei Mischne’s first rabbi, and served the congregation for most its existence. M.D. Blockman served as the congregation’s president for over thirty years. Although Anshei Mischne had 175 members in 1941, the congregation eventually disbanded after most of them moved out of the Pinch to the eastern part of Memphis.

In 1912, 25 Jews from Galicia formed their own congregation, the appropriately named Anshei Galicia (People of Galicia), so they could worship in their preferred style. They acquired a two-story brick synagogue on Jackson Avenue and 2nd Street in the Pinch. With a grocery store on the ground floor and a small sanctuary with seating for fifty worshippers on the second floor, Anshei Galicia paled in comparison to most of the other synagogues in the city. It had never had a full-time rabbi as members always led services. By 1941, the congregation only had sixteen members and soon became defunct.

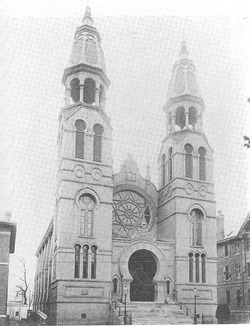

Two other Memphis Orthodox congregations were able to survive the transition from the Pinch to the suburbs, though they ultimately had to unite to be successful. Anshei Sphard was organized by twenty Polish Jews in 1898 who wished to follow the Sephardic rite in their worship. Meeting originally in a rented building at the corner of Main and Beale Streets, Anshei Sphard bought a house on Market Square in 1904 and remodeled it into a synagogue. By 1907, Anshei Sphard had 55 members and $1800 in yearly income. In 1925, they built a new brick synagogue on the same site, which could hold 325 people in its sanctuary. Boasting 235 members in 1941, Anshei Sphard was soon faced with the challenge of having most of its members move out of the Pinch neighborhood. Under the leadership of Rabbi Elijah Stampfer, they built a new synagogue on North Parkway in 1948.

In 1916, a group reorganized Beth El Emeth as an Orthodox congregation and bought Temple Israel’s old synagogue on Poplar Avenue. Abe, Sam, and Barney Plough donated the money for the purchase of the synagogue in honor of their father Moses. By 1941, Beth El Emeth had 285 members. Beth El Emeth remained in the Poplar Street shul until 1957, though like the other Pinch synagogues, they faced the dilemma of having most of its members move to the eastern part of the city. In the late 1950s, they bought property eight miles east of their synagogue on Poplar Avenue, and built an education center there. Soon, Beth El Emeth was holding services at the new site. The plan was to build a new sanctuary on the property, but the congregation’s leadership soon realized that the Orthodox Jewish community was not moving to the area around the building in large numbers. Facing a sharp decline in membership, Beth El Emeth scrapped its plans for a new synagogue. Beth El Emeth even briefly considered affiliating with the Conservative Movement in a bid to attract more members. A handful of prominent Orthodox members of the congregation argued successfully against this idea.

Facing declining numbers and financial hardships, Beth El Emeth and Anshei Sphard agreed to merge in 1966. Four years later, Anshei Sphard-Beth El Emeth moved to a new synagogue on East Yates Road. In 1990, the congregation had 380 member families. This merger proved to be successful as the combined congregation remains a vital part of Memphis’ Jewish community today. For twenty years, the congregation has hosted a kosher barbeque contest that has attracted contestants and hungry observers from across the region. The ASBEE kosher barbeque contest shows how Memphis’s Orthodox Jews have embraced the culture of the South while maintaining their religious traditions.

While Memphis’ various Orthodox congregations have competed for members over the years, they cooperated on the founding and support of the Memphis Hebrew Academy, the first Jewish day school in the South. Founded in 1949, the school was organized by the rabbis of Anshei Sphard, Baron Hirsch, and Beth El Emeth. For its first year, the school was housed at Anshei Sphard, but soon moved to Baron Hirsch’s Menorah Institute facility. Later, the school moved into its own building and changed its name to the Margolin Hebrew Academy, after the Margolin family who were among its founders and longtime financial supporters. In 1964, a Jewish high school, called the Yeshiva of the South, was added. This Orthodox Jewish day school was created to be a barrier against assimilation and to ensure the future of Orthodox Judaism in Memphis. On this count, it has been a great success.

In 1916, a group reorganized Beth El Emeth as an Orthodox congregation and bought Temple Israel’s old synagogue on Poplar Avenue. Abe, Sam, and Barney Plough donated the money for the purchase of the synagogue in honor of their father Moses. By 1941, Beth El Emeth had 285 members. Beth El Emeth remained in the Poplar Street shul until 1957, though like the other Pinch synagogues, they faced the dilemma of having most of its members move to the eastern part of the city. In the late 1950s, they bought property eight miles east of their synagogue on Poplar Avenue, and built an education center there. Soon, Beth El Emeth was holding services at the new site. The plan was to build a new sanctuary on the property, but the congregation’s leadership soon realized that the Orthodox Jewish community was not moving to the area around the building in large numbers. Facing a sharp decline in membership, Beth El Emeth scrapped its plans for a new synagogue. Beth El Emeth even briefly considered affiliating with the Conservative Movement in a bid to attract more members. A handful of prominent Orthodox members of the congregation argued successfully against this idea.

Facing declining numbers and financial hardships, Beth El Emeth and Anshei Sphard agreed to merge in 1966. Four years later, Anshei Sphard-Beth El Emeth moved to a new synagogue on East Yates Road. In 1990, the congregation had 380 member families. This merger proved to be successful as the combined congregation remains a vital part of Memphis’ Jewish community today. For twenty years, the congregation has hosted a kosher barbeque contest that has attracted contestants and hungry observers from across the region. The ASBEE kosher barbeque contest shows how Memphis’s Orthodox Jews have embraced the culture of the South while maintaining their religious traditions.

While Memphis’ various Orthodox congregations have competed for members over the years, they cooperated on the founding and support of the Memphis Hebrew Academy, the first Jewish day school in the South. Founded in 1949, the school was organized by the rabbis of Anshei Sphard, Baron Hirsch, and Beth El Emeth. For its first year, the school was housed at Anshei Sphard, but soon moved to Baron Hirsch’s Menorah Institute facility. Later, the school moved into its own building and changed its name to the Margolin Hebrew Academy, after the Margolin family who were among its founders and longtime financial supporters. In 1964, a Jewish high school, called the Yeshiva of the South, was added. This Orthodox Jewish day school was created to be a barrier against assimilation and to ensure the future of Orthodox Judaism in Memphis. On this count, it has been a great success.

Memphis’ Orthodox community now comfortably resides in the suburban eastern portion of the city. They have made the successful transition from the Jewish enclave of the Pinch to the more diverse suburbs. Orthodox Jews continue to create new institutions. In the 1980s, a group founded Young Israel, which strove to be more observant in its practice than the city’s other Orthodox congregations. In 2008, Young Israel had 90 members and employed Yirmiya Milevsky as its full-time rabbi. Chabad has also opened a congregation in Memphis’ Orthodox Jewish neighborhood.

Memphis’s continuing strong Orthodox Jewish community is somewhat of an anomaly in the South. This thriving Orthodoxy is not the product of Jewish transplants from other parts of the country, as is the case in places like Atlanta, but rather is a reflection of a long and deeply rooted commitment to maintaining traditional Judaism within a relatively small Jewish community.

Memphis’s continuing strong Orthodox Jewish community is somewhat of an anomaly in the South. This thriving Orthodoxy is not the product of Jewish transplants from other parts of the country, as is the case in places like Atlanta, but rather is a reflection of a long and deeply rooted commitment to maintaining traditional Judaism within a relatively small Jewish community.