Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Portsmouth, Virginia

Portsmouth: Historical Overview

Portsmouth, Virginia, has long lived in the shadow of Norfolk, its neighbor across the Elizabeth River. Even the shipyard that has dominated Portsmouth for two centuries is named the Norfolk Naval Shipyard to avoid confusion with the shipyard in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. And yet, Portsmouth developed its own distinct Jewish community that thrived for the first half of the 20th century before transportation improvements and demographic trends led to its decline.

Stories of the Jewish Community in Portsmouth

Norfolk Naval Yard, Portsmouth

Norfolk Naval Yard, Portsmouth

Organized Jewish Life in Portsmouth

While Jews have lived in Portsmouth since the mid-19th century, they did not reach sufficient numbers to form community institutions until the 1880s when a handful of Jewish immigrants from Lithuania settled in the growing city. Portsmouth Jews seem to have started gathering together to pray around 1886. The group had fewer than 20 members initially, but was meeting regularly in a building on High Street as early as 1890. In 1894, they hired a Rev. Altschul to lead the congregation, which became known as Gomley Chesed (Acts of Loving Kindness). Around the same, the congregation established a chevra kadisha (burial society) and acquired land for a cemetery. The congregation Gomley Chesed first appeared in the Portsmouth City Directory in 1897. Rev. A. Chaseman led the congregation from 1899 to 1904. Gomley Chesed was Orthodox, with daily minyans and separate seating for men and women. Rev. Chaseman started a small cheder to teach Hebrew, but only allowed boys to attend. Despite this, women did play a role in the congregation, establishing the Hebrew Ladies Aid Society in 1905 to help Jewish families in need. In 1920, they founded the Ladies Auxiliary. Most all of the early members of Gomley Chesed were immigrants; early congregational records were kept in Yiddish.

While Jews have lived in Portsmouth since the mid-19th century, they did not reach sufficient numbers to form community institutions until the 1880s when a handful of Jewish immigrants from Lithuania settled in the growing city. Portsmouth Jews seem to have started gathering together to pray around 1886. The group had fewer than 20 members initially, but was meeting regularly in a building on High Street as early as 1890. In 1894, they hired a Rev. Altschul to lead the congregation, which became known as Gomley Chesed (Acts of Loving Kindness). Around the same, the congregation established a chevra kadisha (burial society) and acquired land for a cemetery. The congregation Gomley Chesed first appeared in the Portsmouth City Directory in 1897. Rev. A. Chaseman led the congregation from 1899 to 1904. Gomley Chesed was Orthodox, with daily minyans and separate seating for men and women. Rev. Chaseman started a small cheder to teach Hebrew, but only allowed boys to attend. Despite this, women did play a role in the congregation, establishing the Hebrew Ladies Aid Society in 1905 to help Jewish families in need. In 1920, they founded the Ladies Auxiliary. Most all of the early members of Gomley Chesed were immigrants; early congregational records were kept in Yiddish.

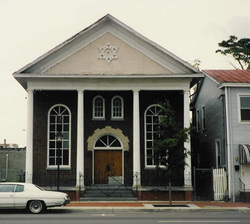

Chevra Thilim.

Chevra Thilim. Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

By the 20th century, Gomley Chesed and the Portsmouth Jewish community were growing quickly. The young congregation soon outgrew its building and bought the Central Methodist Church in 1901. They remodeled the church, creating an apartment as a parsonage, a room for the Hebrew school, and another room to house Jewish wayfarers. In 1902, they added a mikvah (ritual bath) to the building. By 1907, Gomley Chesed had 65 members and 50 students in its religious school. In 1909, Rev. Harry Miller became the teacher and shochet (kosher butcher) for the congregation, remaining until he retired in 1943. In addition, Gomley Chesed hired full-time spiritual leaders, including Rev. Moses Shapiro, who led Gomley Chesed from 1910 to 1917. In 1918, the growing congregation acquired a community center building a few blocks away which it used for its religious school, social events, and congregational meetings. By 1921, Gomley Chesed had 300 members as Portsmouth’s Jewish population had grown to around 2,000 people.

Indeed, Portsmouth’s Jewish community had grown large enough to support a second congregation. In 1916, a small group left Gomley Chesed and established Chevra Thilim (Congregation of the Psalms). The reason for the split is unknown, and both congregations were Orthodox. Their first action as a congregation was to purchase land for a cemetery adjacent to Gomley Chesed’s burial ground. For their first five years, Chevra Thilim met in the second story of a downtown building over a shoe store and a Chinese restaurant. In 1918 they bought land for a synagogue, and finally completed it in 1922. Chevra Thilim employed various short-termed spiritual leaders in its early years.

Indeed, Portsmouth’s Jewish community had grown large enough to support a second congregation. In 1916, a small group left Gomley Chesed and established Chevra Thilim (Congregation of the Psalms). The reason for the split is unknown, and both congregations were Orthodox. Their first action as a congregation was to purchase land for a cemetery adjacent to Gomley Chesed’s burial ground. For their first five years, Chevra Thilim met in the second story of a downtown building over a shoe store and a Chinese restaurant. In 1918 they bought land for a synagogue, and finally completed it in 1922. Chevra Thilim employed various short-termed spiritual leaders in its early years.

Jewish Businesses

Portsmouth’s two Orthodox congregations drew from the city’s growing number of Jewish immigrants, most of whom opened retail businesses. Downtown’s High Street became dominated by Jewish-owned stores, especially after World War I brought new activity and people to the Norfolk Naval Yard. These included Laderberg’s Department Store, Bloomberg’s Department Store, and Lastings Furniture. Opened in 1916, The Famous sold upscale ladies clothing, eventually growing from a small shop to a large corner store. Belle Goodman ran the store for many years. Her son-in-law and daughter Bernard and Zelma Rivin later ran The Famous, before closing it in 1991. The Rapoport family opened a menswear shop on High Street in 1917. As of 2020, third-generation owners Steve and Reid Rapoport still operate the business, The Quality Shops, but in the neighboring cities of Norfolk and Virginia Beach. High Street also had several kosher butcher shops and delis. In addition to these downtown stores, a number of Jewish families owned grocery stores and other small retail businesses in the residential neighborhoods next to the naval yard.

Portsmouth’s two Orthodox congregations drew from the city’s growing number of Jewish immigrants, most of whom opened retail businesses. Downtown’s High Street became dominated by Jewish-owned stores, especially after World War I brought new activity and people to the Norfolk Naval Yard. These included Laderberg’s Department Store, Bloomberg’s Department Store, and Lastings Furniture. Opened in 1916, The Famous sold upscale ladies clothing, eventually growing from a small shop to a large corner store. Belle Goodman ran the store for many years. Her son-in-law and daughter Bernard and Zelma Rivin later ran The Famous, before closing it in 1991. The Rapoport family opened a menswear shop on High Street in 1917. As of 2020, third-generation owners Steve and Reid Rapoport still operate the business, The Quality Shops, but in the neighboring cities of Norfolk and Virginia Beach. High Street also had several kosher butcher shops and delis. In addition to these downtown stores, a number of Jewish families owned grocery stores and other small retail businesses in the residential neighborhoods next to the naval yard.

Jewish Organizations

As the Jewish community flourished in the first half of the 20th century, they established various organizations, including a B’nai B’rith lodge. Portsmouth Jews founded a Zionist society in the early years of the 20th century and later a Hadassah chapter. Portsmouth also had a Workmen’s Circle branch along with a Yiddish school. The Hebrew Ladies Aid Society was one of the most active organizations; in 1919 it had 175 members and raised $1,200 for its charitable work. In the 1950s, Portsmouth Jews established their own country club after the city’s existing clubs excluded them from membership.

As the Jewish community flourished in the first half of the 20th century, they established various organizations, including a B’nai B’rith lodge. Portsmouth Jews founded a Zionist society in the early years of the 20th century and later a Hadassah chapter. Portsmouth also had a Workmen’s Circle branch along with a Yiddish school. The Hebrew Ladies Aid Society was one of the most active organizations; in 1919 it had 175 members and raised $1,200 for its charitable work. In the 1950s, Portsmouth Jews established their own country club after the city’s existing clubs excluded them from membership.

Gomley Chesed's 1955 synagogue.

Gomley Chesed's 1955 synagogue. Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

World War II and the Post-War Years

Portsmouth’s downtown hummed with activity during World War II as the naval yard and other military installations in the area mobilized for war. As many as 40,000 people worked in the naval yard at the height of the war. The Jewish Welfare Board entertained the many Jewish troops stationed in the area at Gomley Chesed’s community center building.

While Portsmouth went back to normal after the war, and the Jewish community remained at around 2,000 people, the 1950s was a period of transition. Gomley Chesed had begun to hire ordained rabbis in the 1930s; one of the longest serving was Eugene Greenfield, who led the congregation from 1936 to 1948. Under his tenure, the congregation instituted Friday night services, and in 1946 formally joined the Conservative movement. In 1948, Gomley Chesed remodeled its sanctuary, removing the Orthodox-style forward facing bimah from the middle of the floor, and replacing it with a stage at the front of the room. The following year, Gomley Chesed instituted mixed-gender seating and welcomed girls into the Hebrew school. The bat mitzvah ceremony became a regular occurrence by the end of the 1950s.

By the early 1950s, Gomley Chesed was no longer an Orthodox immigrant congregation. Its native-born members supported the shift away from Orthodoxy and had begun to move out to the suburbs. Gomley Chesed soon followed suit, dedicating a new synagogue in the city’s suburban Sterling Point neighborhood in 1955. Dr. Simon Greenberg, vice chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary, gave the keynote address at the dedication. Gomley Chesed had 360 families at the time and 330 children in its religious school, which had required them to move to larger facilities.

Some members of Gomley Chesed were not satisfied with Conservative Judaism, and decided to break off and form Portsmouth’s first Reform congregation in 1953. Rabbi Malcolm Stern of Norfolk’s historic Reform congregation Ohev Sholom encouraged the group and helped them to organize Temple Sinai. In its early years, Temple Sinai met in various places, including the Portsmouth Women’s Club, the Suburban Country Club, and even the local Coca-Cola Bottling Works. In 1956, Temple Sinai built a synagogue on Hatton Point Road. Although Temple Sinai was always small, never numbering more than 100 contributing members, it managed to employ a full-time rabbi throughout most of its history, beginning with Rabbi Stanley Kaplan in 1954. Few of these rabbis stayed at Temple Sinai for very long, with the exception of Arthur Steinberg, who led the congregation for 32 years after arriving in 1980.

Portsmouth’s downtown hummed with activity during World War II as the naval yard and other military installations in the area mobilized for war. As many as 40,000 people worked in the naval yard at the height of the war. The Jewish Welfare Board entertained the many Jewish troops stationed in the area at Gomley Chesed’s community center building.

While Portsmouth went back to normal after the war, and the Jewish community remained at around 2,000 people, the 1950s was a period of transition. Gomley Chesed had begun to hire ordained rabbis in the 1930s; one of the longest serving was Eugene Greenfield, who led the congregation from 1936 to 1948. Under his tenure, the congregation instituted Friday night services, and in 1946 formally joined the Conservative movement. In 1948, Gomley Chesed remodeled its sanctuary, removing the Orthodox-style forward facing bimah from the middle of the floor, and replacing it with a stage at the front of the room. The following year, Gomley Chesed instituted mixed-gender seating and welcomed girls into the Hebrew school. The bat mitzvah ceremony became a regular occurrence by the end of the 1950s.

By the early 1950s, Gomley Chesed was no longer an Orthodox immigrant congregation. Its native-born members supported the shift away from Orthodoxy and had begun to move out to the suburbs. Gomley Chesed soon followed suit, dedicating a new synagogue in the city’s suburban Sterling Point neighborhood in 1955. Dr. Simon Greenberg, vice chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary, gave the keynote address at the dedication. Gomley Chesed had 360 families at the time and 330 children in its religious school, which had required them to move to larger facilities.

Some members of Gomley Chesed were not satisfied with Conservative Judaism, and decided to break off and form Portsmouth’s first Reform congregation in 1953. Rabbi Malcolm Stern of Norfolk’s historic Reform congregation Ohev Sholom encouraged the group and helped them to organize Temple Sinai. In its early years, Temple Sinai met in various places, including the Portsmouth Women’s Club, the Suburban Country Club, and even the local Coca-Cola Bottling Works. In 1956, Temple Sinai built a synagogue on Hatton Point Road. Although Temple Sinai was always small, never numbering more than 100 contributing members, it managed to employ a full-time rabbi throughout most of its history, beginning with Rabbi Stanley Kaplan in 1954. Few of these rabbis stayed at Temple Sinai for very long, with the exception of Arthur Steinberg, who led the congregation for 32 years after arriving in 1980.

Temple Sinai.

Temple Sinai. Photo courtesy of Julian Preisler

The Community Declines

The construction of a tunnel linking Portsmouth and Norfolk in the early 1950s was a crucial turning point for the Portsmouth Jewish community and the city itself. The project displaced an entire neighborhood where many Jews lived. Many of those whose property was condemned moved out to the area’s suburbs, especially Virginia Beach. Whereas before one had to take a ferry across the Elizabeth River, it was now much easier to drive back and forth between Portsmouth and Norfolk. This led to increased suburbanization and the rise of strip malls which drained the foot traffic from High Street. People could now easily shop at Norfolk’s stores and didn’t have to rely on those remaining in downtown Portsmouth. Jewish-owned stores began to close or move out of Portsmouth. By 1980, only about 1,000 Jews lived in Portsmouth. In 2013, only one Jewish-owned business, the Crockin Furniture Store, remained open on High Street, which was once been dominated by Jewish merchants.

This decline had a significant impact on Portsmouth’s three Jewish congregations. Chevra Thilim, which remained Orthodox and was still located downtown, began to shrink from its peak of 200 members. Its last spiritual leader was Ben Asher, who served the congregation from 1963 to 1973. By the mid-1980s, Chevra Thilim could no longer attract a minyan and became defunct. Temple Sinai also saw its membership shrink as most of the children of the founding members moved away from Portsmouth after they grew up. By 2012, faced with a shrinking membership and a deteriorating building that required a lot of repair work, the remaining 60 or so families of Temple Sinai decided to close their synagogue and merge with the much larger Ohev Sholom in Norfolk. Temple Sinai’s stained glass windows were installed in Ohev Sholom’s chapel, and Rabbi Arthur Steinberg was given rabbi emeritus status at Ohev Sholom.

The construction of a tunnel linking Portsmouth and Norfolk in the early 1950s was a crucial turning point for the Portsmouth Jewish community and the city itself. The project displaced an entire neighborhood where many Jews lived. Many of those whose property was condemned moved out to the area’s suburbs, especially Virginia Beach. Whereas before one had to take a ferry across the Elizabeth River, it was now much easier to drive back and forth between Portsmouth and Norfolk. This led to increased suburbanization and the rise of strip malls which drained the foot traffic from High Street. People could now easily shop at Norfolk’s stores and didn’t have to rely on those remaining in downtown Portsmouth. Jewish-owned stores began to close or move out of Portsmouth. By 1980, only about 1,000 Jews lived in Portsmouth. In 2013, only one Jewish-owned business, the Crockin Furniture Store, remained open on High Street, which was once been dominated by Jewish merchants.

This decline had a significant impact on Portsmouth’s three Jewish congregations. Chevra Thilim, which remained Orthodox and was still located downtown, began to shrink from its peak of 200 members. Its last spiritual leader was Ben Asher, who served the congregation from 1963 to 1973. By the mid-1980s, Chevra Thilim could no longer attract a minyan and became defunct. Temple Sinai also saw its membership shrink as most of the children of the founding members moved away from Portsmouth after they grew up. By 2012, faced with a shrinking membership and a deteriorating building that required a lot of repair work, the remaining 60 or so families of Temple Sinai decided to close their synagogue and merge with the much larger Ohev Sholom in Norfolk. Temple Sinai’s stained glass windows were installed in Ohev Sholom’s chapel, and Rabbi Arthur Steinberg was given rabbi emeritus status at Ohev Sholom.

The Jewish Community in Portsmouth Today

Gomley Chesed, the last Jewish congregation in Portsmouth, survived until 2014. In 1982 the synagogue still had 350 families. Rabbi Philip Krohn led the congregation from 1984 to 2008, but the congregation shrank to only 70 households in 2013. In 2014, after the last High Holiday service, Gomley Chesed closed permanently, and many of its remaining members joined the Conservative Beth El Synagogue in Norfolk. Thus, there are no longer any active synagogues in the City of Portsmouth.

Despite this decline, the Portsmouth Jewish community remains vital. A group of local Jews worked to acquire the former synagogue of Chevra Thilim in 2002. After a successful fundraising effort, they restored the building and opened it as the Jewish Museum and Cultural Center in 2008. The museum houses artifacts related to the history of Jews in the Hampton Roads area and sponsors a speaker series that brings in leading historians of American Jewish history. While Jews have largely moved on from Portsmouth into other parts of Hampton Roads, this museum will help ensure that the town’s proud Jewish legacy will not be forgotten.

Despite this decline, the Portsmouth Jewish community remains vital. A group of local Jews worked to acquire the former synagogue of Chevra Thilim in 2002. After a successful fundraising effort, they restored the building and opened it as the Jewish Museum and Cultural Center in 2008. The museum houses artifacts related to the history of Jews in the Hampton Roads area and sponsors a speaker series that brings in leading historians of American Jewish history. While Jews have largely moved on from Portsmouth into other parts of Hampton Roads, this museum will help ensure that the town’s proud Jewish legacy will not be forgotten.