Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Cleveland, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Cleveland

Overview

Cleveland, Mississippi, is one of the two seats of Bolivar County. The town was founded in 1869 and named in honor of President Grover Cleveland. Prior to the Civil War the area was sparsely settled, and enslaved African Americans made up the majority of its residents. Bolivar County’s population grew rapidly during and after Reconstruction as the area’s timber resources and fertile Delta soil attracted white landowners, Black agricultural laborers in search of economic advancement, and business owners who served farms and farm workers.

The earliest permanent Jewish residents of Cleveland arrived around 1890, not long after the Louisville, New Orleans & Texas Railroad improved connections between the local economy and more distant markets. Jewish shop owners soon became a visible presence in several of the towns in and around Bolivar County, but an organized Jewish community did not take shape until the early 20th century. Since then, Cleveland’s Adath Israel has served as a Jewish hub for the surrounding area, even as the Jewish population has waxed and waned with the economic fortunes of the Mississippi Delta.

The earliest permanent Jewish residents of Cleveland arrived around 1890, not long after the Louisville, New Orleans & Texas Railroad improved connections between the local economy and more distant markets. Jewish shop owners soon became a visible presence in several of the towns in and around Bolivar County, but an organized Jewish community did not take shape until the early 20th century. Since then, Cleveland’s Adath Israel has served as a Jewish hub for the surrounding area, even as the Jewish population has waxed and waned with the economic fortunes of the Mississippi Delta.

Early Jewish Settlement and Continued Growth

Artie, I. A., and Eva Kamien in front of the family store. Photo by Bill Aron.

Artie, I. A., and Eva Kamien in front of the family store. Photo by Bill Aron.

Census records indicate that Jewish peddlers or merchants lived in Bolivar County by 1860. These first Jewish residents were usually young, single men who traded in settlements along the Mississippi River, and they do not seem to have put down roots in the area. By 1880 Bolivar County had attracted a handful of long term Jewish residents, including Julius H. Zadeck, who eventually owned a store in Gunnison.

Jewish settlement in the inland portion of Bolivar County seems to have come somewhat later. The first known Jewish family in Cleveland were the Kamiens. Leon and Rachel Kamien were born in Poland and the German states, respectively. They met in New Orleans in the late 1870s and settled in Mississippi sometime before 1880. By 1892, the family had established their first clothing store in Cleveland. In 1904, Leon partnered with his son Isadore to open another store, called Kamien's. The family business was quite successful, and the Kamiens became leading philanthropists in town, donating land for the first Methodist and Baptist churches. The Kamiens’ store spanned four generations and continued into the early 21st century under the management of Artie Kamien.

Other Jews began to arrive and set down roots in the area around the turn of the century. Maude Kamien, daughter of Leon, married Abe Miller, a member of a popular merchant family. Emil Seelbinder and his wife Sophia—Rachel Kamien's sister—came from Germany and operated a dairy farm in the area. In 1926, Kaplan’s Variety Store advertised in the local newspaper with its slogan, “So Much for So Little.” Klingman Chevrolet started in the 1920s and lasted into the 1930s. Another Jewish-owned car dealerships, Kossman’s, sold General Motors vehicles until the early 21st century. Fink’s Drug Store and the Solomon Coal and Transfer Company were also owned by Jews. While Jewish names filled the listings of local businesses in the area, many Jews also got involved in local politics. Such examples included mayors from neighboring towns such as Jacob Cohen of Shaw (1892-1897) and M.J. Dattel of Rosedale (1970s).

Jewish settlement in the inland portion of Bolivar County seems to have come somewhat later. The first known Jewish family in Cleveland were the Kamiens. Leon and Rachel Kamien were born in Poland and the German states, respectively. They met in New Orleans in the late 1870s and settled in Mississippi sometime before 1880. By 1892, the family had established their first clothing store in Cleveland. In 1904, Leon partnered with his son Isadore to open another store, called Kamien's. The family business was quite successful, and the Kamiens became leading philanthropists in town, donating land for the first Methodist and Baptist churches. The Kamiens’ store spanned four generations and continued into the early 21st century under the management of Artie Kamien.

Other Jews began to arrive and set down roots in the area around the turn of the century. Maude Kamien, daughter of Leon, married Abe Miller, a member of a popular merchant family. Emil Seelbinder and his wife Sophia—Rachel Kamien's sister—came from Germany and operated a dairy farm in the area. In 1926, Kaplan’s Variety Store advertised in the local newspaper with its slogan, “So Much for So Little.” Klingman Chevrolet started in the 1920s and lasted into the 1930s. Another Jewish-owned car dealerships, Kossman’s, sold General Motors vehicles until the early 21st century. Fink’s Drug Store and the Solomon Coal and Transfer Company were also owned by Jews. While Jewish names filled the listings of local businesses in the area, many Jews also got involved in local politics. Such examples included mayors from neighboring towns such as Jacob Cohen of Shaw (1892-1897) and M.J. Dattel of Rosedale (1970s).

Organized Jewish Life

By the early 1920s, about ten Jewish families lived in Cleveland, with additional Jewish families living in surrounding towns. At that point the only Jewish organization in the area was the “Busy Bees,” made up of women in Ruleville and Drew (both towns are a short distance east of Cleveland in Sunflower County). The Busy Bees—founded in 1915—met as a Jewish sewing circle, held discussion sessions, and conducted charitable work. The group joined the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods in 1927 and later merged with the Sisterhood of the Cleveland Jewish congregation.

Cleveland’s Jews began organizing in the early 1920s, spurred in part by the desire to provide a Jewish education for their children. In the spring of 1922, Fannie Weinstein invited Greenville’s rabbi, Samuel A. Rabinowitz, to speak at the local Cleveland PTA. During his visit, the Jews of Cleveland met with him and discussed forming a local religious school. From this informal meeting and a second gathering in a room on the top of Cleveland State Bank, Rabbi Rabinowitz agreed to lead the religious school, which became the first Jewish religious institution in Cleveland. The school, known as the Community Hebrew School, catered to Jewish children throughout Bolivar County and eventually Sunflower County as well. Conducted at the Cleveland Consolidated School, the religious school first held classes in 1923. The school proved to be a great success, with 53 children coming on Sundays in its first year.

That year also marked the beginning of congregational worship in Cleveland, which drew out-of-town participants from Drew, Ruleville, Rosedale, Shaw, Boyle, Pace, Merigold, and Shelby. Jacob Borodofsky was the first president, and an adult bible class met every Sunday, led by knowledgeable congregation members. Rabbi Rabinowitz came to Cleveland on the last Sunday of each month to lead services. For its first four years, the group worshipped in a local high school auditorium, and members soon began to raise money to build a permanent home for the congregation. Between 1926 and 1927, Joe Fink and Leo Shoenholz led the capital campaign for the first building of the congregation they now called Adath Israel (Community of Israel). Their efforts drew support from outside the Jewish community and from outside the local community. Non-Jews donated nearly $4,000 for the project, and wholesale suppliers in Memphis and St. Louis contributed $1,200. The small Jewish community of Merigold raised $750, while Mrs. Dattel and others in Rosedale secured $1,000 in contributions.

Cleveland’s Jews began organizing in the early 1920s, spurred in part by the desire to provide a Jewish education for their children. In the spring of 1922, Fannie Weinstein invited Greenville’s rabbi, Samuel A. Rabinowitz, to speak at the local Cleveland PTA. During his visit, the Jews of Cleveland met with him and discussed forming a local religious school. From this informal meeting and a second gathering in a room on the top of Cleveland State Bank, Rabbi Rabinowitz agreed to lead the religious school, which became the first Jewish religious institution in Cleveland. The school, known as the Community Hebrew School, catered to Jewish children throughout Bolivar County and eventually Sunflower County as well. Conducted at the Cleveland Consolidated School, the religious school first held classes in 1923. The school proved to be a great success, with 53 children coming on Sundays in its first year.

That year also marked the beginning of congregational worship in Cleveland, which drew out-of-town participants from Drew, Ruleville, Rosedale, Shaw, Boyle, Pace, Merigold, and Shelby. Jacob Borodofsky was the first president, and an adult bible class met every Sunday, led by knowledgeable congregation members. Rabbi Rabinowitz came to Cleveland on the last Sunday of each month to lead services. For its first four years, the group worshipped in a local high school auditorium, and members soon began to raise money to build a permanent home for the congregation. Between 1926 and 1927, Joe Fink and Leo Shoenholz led the capital campaign for the first building of the congregation they now called Adath Israel (Community of Israel). Their efforts drew support from outside the Jewish community and from outside the local community. Non-Jews donated nearly $4,000 for the project, and wholesale suppliers in Memphis and St. Louis contributed $1,200. The small Jewish community of Merigold raised $750, while Mrs. Dattel and others in Rosedale secured $1,000 in contributions.

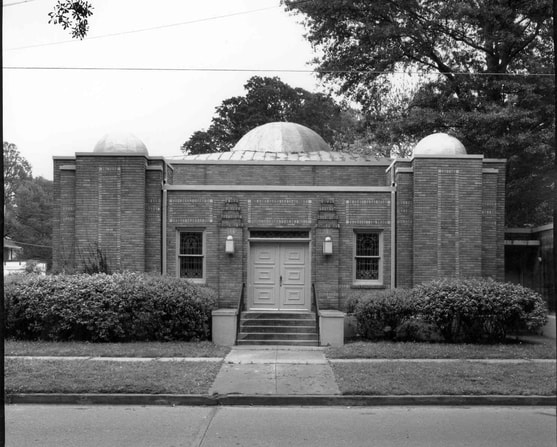

Adath Israel. Photo by Bill Aron.

Adath Israel. Photo by Bill Aron.

Work began on the new building in the fall of 1926. In February 1927, Adath Israel members dedicated their Moorish style building at the corner of Bolivar and Shelby Streets. In September of that year, Adath Israel members celebrated their first high holiday services in the new building, conducted by a student rabbi. The next year the congregation hired Rabbi Jacob Halevi as their resident rabbi. His tenure continued until 1931, after which Carl Schorr, Hirsch L. Freund, and Newton Friedman served the congregation. In 1934, Adath Israel joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations and began using the Reform Union Prayer Book. Interestingly, Cleveland never had a Jewish cemetery, so some Jews were buried in the main city cemetery or in the Jewish cemetery section in Greenville. According to local lore, the reason for never starting a cemetery was that no one wanted to be the first to be buried there.

With the founding of a Cleveland area B’nai B’rith chapter in 1928, local men and women had separate fraternal and auxiliary organizations in the Jewish community. The Cleveland B’nai B’rith initially attracted 74 members and remained active for decades, while women’s groups continued to play an important role in Jewish life. In 1927 a “Main Line Sisterhood” started in Cleveland and a “Riverside Sisterhood” began to serve western Bolivar County. These operated separately for years before the Ruleville-Drew contingent (the “Busy Bees”) merged with the other, previously unified sisterhoods in 1969. Women’s activities included organizing religious school, fundraising for the congregation, overseeing the furnishing of the synagogue, and contributing to philanthropic efforts in the broader community.

Soon after the new building was constructed, natural and economic disasters disrupted life in Cleveland and the Delta. Bolivar County was not as heavily affected by the 1927 Mississippi River Flood as areas farther South, but Cleveland was the site of a large Red Cross relief plant. Two years later, the Great Depression wreaked havoc on Mississippi’s already struggling (and vastly inequitable) agricultural economy. Cleveland’s Adath Israel managed to weather these crises. While tight budgets caused the synagogue to fall into disrepair, charity drives at the synagogue brought in over a thousand dollars annually and the congregation managed to pay for full-time rabbinical services. Membership also grew during this challenging period, increasing from 70 to 89 families between 1928 and 1937.

With the founding of a Cleveland area B’nai B’rith chapter in 1928, local men and women had separate fraternal and auxiliary organizations in the Jewish community. The Cleveland B’nai B’rith initially attracted 74 members and remained active for decades, while women’s groups continued to play an important role in Jewish life. In 1927 a “Main Line Sisterhood” started in Cleveland and a “Riverside Sisterhood” began to serve western Bolivar County. These operated separately for years before the Ruleville-Drew contingent (the “Busy Bees”) merged with the other, previously unified sisterhoods in 1969. Women’s activities included organizing religious school, fundraising for the congregation, overseeing the furnishing of the synagogue, and contributing to philanthropic efforts in the broader community.

Soon after the new building was constructed, natural and economic disasters disrupted life in Cleveland and the Delta. Bolivar County was not as heavily affected by the 1927 Mississippi River Flood as areas farther South, but Cleveland was the site of a large Red Cross relief plant. Two years later, the Great Depression wreaked havoc on Mississippi’s already struggling (and vastly inequitable) agricultural economy. Cleveland’s Adath Israel managed to weather these crises. While tight budgets caused the synagogue to fall into disrepair, charity drives at the synagogue brought in over a thousand dollars annually and the congregation managed to pay for full-time rabbinical services. Membership also grew during this challenging period, increasing from 70 to 89 families between 1928 and 1937.

World War II and the Postwar Era

Following the United States’ entry into the second World War, 46 Jewish men from the Cleveland area entered the armed forces. Although many of them saw combat, only Lt. Herbert Miller of Drew died during the war. Local Jews on the homefront also contributed to war efforts; the Adath Israel Sisterhood sold “more Defense Bonds than any other group” and received a Meritorious Service Award in recognition of their work.

By the end of the war the nation’s general economic recovery was evident in Cleveland, and the city’s Jewish community entered its “golden age.” Two local developments improved prospects for local merchants by bringing stable employment and reliable customers to town in this era: industrial growth and the emergence of Delta State Teachers College (now Delta State University). Between 1937 and 1948, the Jewish population of Cleveland grew from 54 to 250.

By the late 1940s Adath Israel boasted more than 100 members, and nearly 75 children attended religious school there in the mid-1950s. Sunday school and Friday night services were staples of religious life for the local community. A series of rabbis served the congregation over the years, including Louis Josephson, Julian Feingold, Simon Cohen, Morris Shapiro, and Henry Schwartz. In 1950 the congregation built a $30,000 annex, which included a social hall, kitchen, and new classrooms. Members of the congregation were strong supporters of the fledgling State of Israel with Mose Hyman and Leo Shoenholz leading an Israel bond drive which raised $35,000 in the late 1940s.

During the years after World War II , Cleveland Jews remained concentrated in retail trade. Sydney Howard Hytken ran his high fashion ladies’ ready-to-wear shop called “The Parisian.” Other stores included Kossman Appliance Company, Marcel Davidow’s Western Auto Associate Store, Kay’s Style Shop, and Levingston Furniture. In Shaw, Harry and Sarah Rubenstein sold shoes, dresses, and work clothes to farming families that bought clothes once or twice a year; they finally closed the store in 1977 after over 60 years in business.

In 1957 Adath Israel finally began to enjoy some rabbinical stability with the arrival of Rabbi Moses Landau, who served the congregation well into the 1990s. Under his leadership, the congregation grew and became more active. In the 1960s, they renovated their sanctuary, built a rabbi’s study, and acquired a parsonage for the rabbi. Cleveland’s Jewish community continued to thrive during the 1960s and early 1970s, reaching its peak Jewish population of 280 individuals during this era.

By the end of the war the nation’s general economic recovery was evident in Cleveland, and the city’s Jewish community entered its “golden age.” Two local developments improved prospects for local merchants by bringing stable employment and reliable customers to town in this era: industrial growth and the emergence of Delta State Teachers College (now Delta State University). Between 1937 and 1948, the Jewish population of Cleveland grew from 54 to 250.

By the late 1940s Adath Israel boasted more than 100 members, and nearly 75 children attended religious school there in the mid-1950s. Sunday school and Friday night services were staples of religious life for the local community. A series of rabbis served the congregation over the years, including Louis Josephson, Julian Feingold, Simon Cohen, Morris Shapiro, and Henry Schwartz. In 1950 the congregation built a $30,000 annex, which included a social hall, kitchen, and new classrooms. Members of the congregation were strong supporters of the fledgling State of Israel with Mose Hyman and Leo Shoenholz leading an Israel bond drive which raised $35,000 in the late 1940s.

During the years after World War II , Cleveland Jews remained concentrated in retail trade. Sydney Howard Hytken ran his high fashion ladies’ ready-to-wear shop called “The Parisian.” Other stores included Kossman Appliance Company, Marcel Davidow’s Western Auto Associate Store, Kay’s Style Shop, and Levingston Furniture. In Shaw, Harry and Sarah Rubenstein sold shoes, dresses, and work clothes to farming families that bought clothes once or twice a year; they finally closed the store in 1977 after over 60 years in business.

In 1957 Adath Israel finally began to enjoy some rabbinical stability with the arrival of Rabbi Moses Landau, who served the congregation well into the 1990s. Under his leadership, the congregation grew and became more active. In the 1960s, they renovated their sanctuary, built a rabbi’s study, and acquired a parsonage for the rabbi. Cleveland’s Jewish community continued to thrive during the 1960s and early 1970s, reaching its peak Jewish population of 280 individuals during this era.

Adath Israel confirmation class with Rabbi Moses Landau, c. 1960s. Courtesy of the congregation.

Adath Israel confirmation class with Rabbi Moses Landau, c. 1960s. Courtesy of the congregation.

As Adath Israel prospered it began to offer more programs, especially for Jewish youth. Although Sylvia Sklar of Ruleville had served as chairperson of the Mississippi Federation of Temple Youth in 1946, Adath Israel did not establish its own youth group until the following year. By the early 1960s it was one of the largest temple youth groups in the state. In addition to attracting Jewish teenagers from Cleveland and nearby small towns, the youth group also included peers from Temple Beth Israel in Greenwood, a smaller congregation. Youth group participants came from as far away as Winona, Mississippi, about 70 miles east of Cleveland. Macy Hart, of Winona, participated in the Cleveland group and became national president of the North American Federation of Temple Youth in the late 1960s. (He later served as the director of Henry S. Jacobs Camp and founded the Institute of Southern Jewish Life in 2000.)

The Jewish Community in Cleveland Today

The Jewish population in and around Cleveland began to decline sharply by the 1980s. The children of local Jewish families typically left to seek educational and career opportunities in larger cities, and many older community members eventually moved to be closer to their children. Memphis—a two-hour drive from Cleveland—attracted many Bolivar County Jews. Changing economic circumstances contributed to the decline, as a shrinking customer base and competition from large chains threatened the viability of the area’s Jewish retail businesses.

As in other small towns, the number of Jews dwindled as mortality and out-migration greatly exceeded any new arrivals. Adath Israel operated a religious school into the 1980s but has had little need for one since then. The Kamien’s department store and Kossman’s car dealership were the last two Jewish businesses open in Cleveland, both closing in the late 2010s. As of 2020 there are no Jews living in the smaller towns, such as Ruleville and Drew, that used to participate in the local community. Of the remaining dozen or so households that belong to Adath Israel, several come from Clarksdale, where the Jewish congregation closed in 2003.

Despite declining membership, Adath Israel has persisted into the twenty-first century. For many years the congregation has enjoyed monthly visits from Rabbi Harry Danziger, emeritus rabbi of Temple Israel in Memphis. Additionally, the congregation has helped cover the costs of maintaining a nearly 100-year-old building by renting the space to churches for regular church services and vacation bible schools during the summer. While the COVID-19 pandemic forced the Adath Israel to suspend activities in 2020, religious services have since resumed.

As in other small towns, the number of Jews dwindled as mortality and out-migration greatly exceeded any new arrivals. Adath Israel operated a religious school into the 1980s but has had little need for one since then. The Kamien’s department store and Kossman’s car dealership were the last two Jewish businesses open in Cleveland, both closing in the late 2010s. As of 2020 there are no Jews living in the smaller towns, such as Ruleville and Drew, that used to participate in the local community. Of the remaining dozen or so households that belong to Adath Israel, several come from Clarksdale, where the Jewish congregation closed in 2003.

Despite declining membership, Adath Israel has persisted into the twenty-first century. For many years the congregation has enjoyed monthly visits from Rabbi Harry Danziger, emeritus rabbi of Temple Israel in Memphis. Additionally, the congregation has helped cover the costs of maintaining a nearly 100-year-old building by renting the space to churches for regular church services and vacation bible schools during the summer. While the COVID-19 pandemic forced the Adath Israel to suspend activities in 2020, religious services have since resumed.

Updated September 2023.