Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Tupelo, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Tupelo

Overview

|

Tupelo, a small city in northeast Mississippi, is most famous for being the birthplace of Elvis Presley, but the seat of Lee County has been home to Jews for well over a century. The first Jewish settlers in the area lived in Harrisburg, a defunct town that predated the founding of Lee County. Their numbers increased after the arrival of the railroad in the 1850s.

While Tupelo has never had a large Jewish population, the city's mid-20th-century growth supported the development of a small but active congregation. Although the city has continued to grow in the early 21st century, the Jewish population has not kept pace. |

Early Jewish Settlers

In the 18th century the eventual site of Tupelo was near the heart of Chickasaw Nation territory. Euro-American settlement increased after Indian Removal in the 1830s, and northeast Mississippi soon developed a more diversified agricultural economy than the western portions of the state, which primarily grew cotton. Prior to the Civil War and Emancipation, enslaved Black workers made up approximately one third of the population, a smaller proportion than in cotton-dominated counties. Agricultural settlements paved the way for commercial ventures, and Jews started to arrive in and around Tupelo by the middle of the century. One of the first known Jewish residents of Tupelo was Simon Wolf, an itinerant peddler who settled in the area around 1853 and established a store.

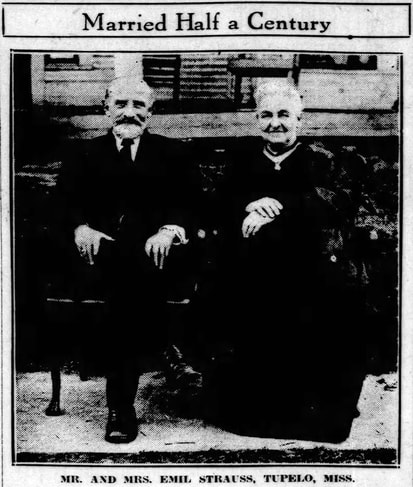

Commercial Appeal (Memphis), June 14, 1924.

Commercial Appeal (Memphis), June 14, 1924.

Other Jewish settlers followed, like Emil Strauss. Born in Germany in 1850, Strauss first came to the United States in 1869, settling in Selma, Alabama, where his brother already lived. In 1873, he returned to Germany to marry his sweetheart, Rosalie Sondheimer, and the couple migrated to the US five years later, accompanied by their three young children. The Strauss family settled in Fulton, Mississippi—approximately 20 miles east of Tupelo—where they opened a grocery store. Sometime in the early 1880s, they moved to Tupelo and opened a butcher shop. Although the shop was probably not kosher, the Strauss family did not abandon all religious traditions. In December 1886 they held a bris (circumcision ceremony) for their newborn son at their Tupelo home, which was covered in the local newspaper. (The editor was one of the guests.) Many local non-Jews enjoyed a “magnificent dinner” after the ritual. Jews from others towns also attended, indicating the existence of (at least) a loosely connected Jewish community, even in the absence of a nearby congregation.

Emil Strauss was a popular citizen in Tupelo. He belonged to the local Masonic Lodge and the Knights of Pythias. Although he had been a teenager in Germany at the time of the Civil War, the local camp of Confederate Veterans made him an honorary member, a fact that reflected his acceptance among white Christians. According to the local newspaper, when he and Rosalie celebrated their 50th anniversary in 1923, “the entire town went to their home with gifts that carried with them the love and confidence of the people of Tupelo.” Following Emil’s death a few years later, Rabbi Harry Ettelson of Temple Israel in Memphis conducted the funeral, assisted by J.D. Hunter, a local Christian minister and a longtime friend of Strauss. Since there was no Jewish cemetery in Tupelo, Strauss was buried in Glenwood Cemetery. The most lasting evidence of this early Jewish settler is Strauss Street, named in his honor.

Emil Strauss was a popular citizen in Tupelo. He belonged to the local Masonic Lodge and the Knights of Pythias. Although he had been a teenager in Germany at the time of the Civil War, the local camp of Confederate Veterans made him an honorary member, a fact that reflected his acceptance among white Christians. According to the local newspaper, when he and Rosalie celebrated their 50th anniversary in 1923, “the entire town went to their home with gifts that carried with them the love and confidence of the people of Tupelo.” Following Emil’s death a few years later, Rabbi Harry Ettelson of Temple Israel in Memphis conducted the funeral, assisted by J.D. Hunter, a local Christian minister and a longtime friend of Strauss. Since there was no Jewish cemetery in Tupelo, Strauss was buried in Glenwood Cemetery. The most lasting evidence of this early Jewish settler is Strauss Street, named in his honor.

Organized Jewish Life

At the turn of the century there were still only a few Jewish families permanently settled in Tupelo. Around 1930, the town claimed 20 Jewish residents out of an overall population of 6,000 individuals. By the end of the decade, however, the Federal response to the Great Depression transformed the area. In 1935 Tupelo became the first city to receive electrical power from the Tennessee Valley Authority. The availability of cheap electricity, newly paved roads, and cheap southern labor made Tupelo and nearby towns attractive to manufacturers and precipitated a population boom that, in turn, drew in new Jewish retailers.

By the late 1930s there were enough Jews in the towns of northeast Mississippi to form the first Jewish organizations in the area. Based in Tupelo, the Northeast Mississippi Sisterhood formed in 1936 under the leadership of Marion Peltz and Mrs. Sol Weiner. Through the sisterhood local women socialized and undertook charitable work in a Jewish setting. Mrs. Weiner’s husband Sol led a similar effort two years later to establish Tupelo’s B’nai Brith Lodge. The area’s first Sunday School also started in 1938, spearheaded by Sisterhood President Carrie Scharf. Held in the Tupelo City Hall, it began with eleven students and four teachers: Reva Feldman, Lucille Weiner, Ben Weiner and Jerry Sherman.

By the late 1930s there were enough Jews in the towns of northeast Mississippi to form the first Jewish organizations in the area. Based in Tupelo, the Northeast Mississippi Sisterhood formed in 1936 under the leadership of Marion Peltz and Mrs. Sol Weiner. Through the sisterhood local women socialized and undertook charitable work in a Jewish setting. Mrs. Weiner’s husband Sol led a similar effort two years later to establish Tupelo’s B’nai Brith Lodge. The area’s first Sunday School also started in 1938, spearheaded by Sisterhood President Carrie Scharf. Held in the Tupelo City Hall, it began with eleven students and four teachers: Reva Feldman, Lucille Weiner, Ben Weiner and Jerry Sherman.

With these organizations already in place, the next step for Tupelo Jews was to organize a congregation. After months of conducting informal services in various homes, the Jewish community officially organized Temple B’nai Israel on August 24, 1939, with Sol Weiner as its first president. They initially met in the Tupelo City Hall and then rented space above the Fooks’ Chevrolet dealership on South Spring Street. (Congregant Lewis Fooks owned the dealership.) That year, a student rabbi from the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati made the trip to conduct services for the high holidays. In 1945, the congregation added a holy ark and received its first Torah from the Vine Street Temple in Nashville.

A Growing Community

By the end of World War II northeast Mississippi emerged as a regional manufacturing center. Industrial development continued to spur population growth, and the Jewish community increased in size. A 1948 study showed that 200 Jews lived in the Lee County area, many of them retail business owners. Tupelo Jews owned a number of prominent businesses in the 1950s, including Gage and Weil Junk Company and multiple general merchandise stores: Allen’s, Kuhn’s, Kleban and Matz, and Peltz’s Dry Goods Store. Weiner’s Department Store sold clothing using the slogan, “Outfitters for the Family,” while RE-NAL’s Ladies Shop dubbed itself “The Style Center of Tupelo.” Other Jewish businesses served neighboring towns, including Feldman’s Department store in Booneville. Many of Jewish business owners participate in fraternal and civic organizations, such as the Masons and Knights of Pythias Lodge, and their involvement in these groups marked a high degree of acceptance among the greater Tupelo community.

With a larger Jewish population in the area, Temple B’nai Israel needed a new, bigger location to accommodate its members. In 1953 the congregation moved to the space over Biggs Furniture Store but began exploring the possibility of building their own place of worship by 1955 Manny Davis, who owned a sportswear manufacturing business in Okolona, made a large contribution to the building fund and offered to match the contributions of other members. Morris Gorden, who owned a successful store in Baldwyn, used his business contacts with Jews in other cities to raise money for a new house of worship. The building committee printed a brochure which included an architect’s rendering of the planned synagogue and a personal appeal from congregation president Maurice Stein. Stein called for contributions from “friends and neighbors” in order to build a facility that would “be a vital factor in the civic, cultural, and spiritual life of this community.” Sol Weiner, who served as secretary and treasurer of B’nai Israel for 40 years, collected these donations.

With a larger Jewish population in the area, Temple B’nai Israel needed a new, bigger location to accommodate its members. In 1953 the congregation moved to the space over Biggs Furniture Store but began exploring the possibility of building their own place of worship by 1955 Manny Davis, who owned a sportswear manufacturing business in Okolona, made a large contribution to the building fund and offered to match the contributions of other members. Morris Gorden, who owned a successful store in Baldwyn, used his business contacts with Jews in other cities to raise money for a new house of worship. The building committee printed a brochure which included an architect’s rendering of the planned synagogue and a personal appeal from congregation president Maurice Stein. Stein called for contributions from “friends and neighbors” in order to build a facility that would “be a vital factor in the civic, cultural, and spiritual life of this community.” Sol Weiner, who served as secretary and treasurer of B’nai Israel for 40 years, collected these donations.

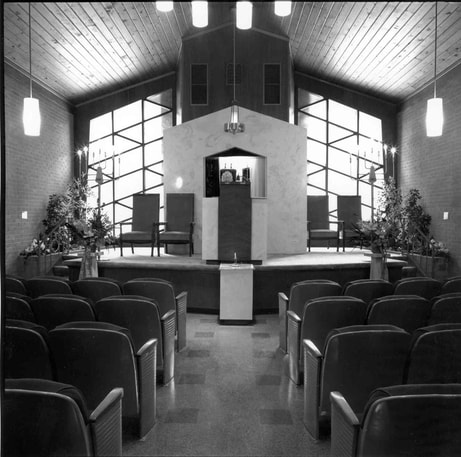

The sanctuary of B'nai Israel. Photo by Bill Aron.

The sanctuary of B'nai Israel. Photo by Bill Aron.

The building process demonstrated strong affinity between Tupelo’s Jewish community and white Christians. Local non-Jews accounted for 41 percent of the 88 individual donors to the building fund. In addition, 12 local companies, including nine banks, donated to the cause. When time came for a dedication ceremony, many area banks and manufacturing companies bought ads in the event program; the Bryan Brothers packing Company in West Point even too the opportunity to advertise its “Prairie Belt Bacon.” The synagogue dedication took place on September 1, 1957, and Tupelo mayor James Bullard gave remarks, as did the pastor of the First Methodist Church.

B’nai Israel has never been defined by its adherence to a single denominational movement, and its early members came from a variety of Jewish backgrounds. At the dedication ceremony, Rabbi Meyer Passow of Memphis’ conservative congregation delivered the featured address, while Reform Rabbi Alexander Kline of Clarksdale gave the benediction. The congregation held bar mitzvah ceremonies, which had been abandoned in many Reform congregations across the country, as well as confirmation, a ceremony which originated with Reform Judaism. Over the years, B’nai Israel has succeeded in balancing the different religious practices of its members, though the congregation trended toward Reform worship by the early 21st century.

In addition to the congregation’s flexibility in religious practice, B’nai Israel served a widespread membership. At the time of the synagogue dedication, member families lived in 13 different towns, some as far as 75 miles away. The congregation sometimes hired a student rabbi on the High Holidays, but lay leaders conducted services on most occasions. In 1957, B’nai Israel held Shabbat services every Friday night and a weekly Sunday school, all without rabbinic supervision. A number of members have led services over the years. In the 1950s and 1960s Murray Stein, who owned a dress shop on Main Street, acted as the lay leader. The temple dedication program identifies Stein as the “lay rabbi.” and he was even active in the local clergy association. Since his death in 1968, several other members have served as worship leaders.

B’nai Israel has never been defined by its adherence to a single denominational movement, and its early members came from a variety of Jewish backgrounds. At the dedication ceremony, Rabbi Meyer Passow of Memphis’ conservative congregation delivered the featured address, while Reform Rabbi Alexander Kline of Clarksdale gave the benediction. The congregation held bar mitzvah ceremonies, which had been abandoned in many Reform congregations across the country, as well as confirmation, a ceremony which originated with Reform Judaism. Over the years, B’nai Israel has succeeded in balancing the different religious practices of its members, though the congregation trended toward Reform worship by the early 21st century.

In addition to the congregation’s flexibility in religious practice, B’nai Israel served a widespread membership. At the time of the synagogue dedication, member families lived in 13 different towns, some as far as 75 miles away. The congregation sometimes hired a student rabbi on the High Holidays, but lay leaders conducted services on most occasions. In 1957, B’nai Israel held Shabbat services every Friday night and a weekly Sunday school, all without rabbinic supervision. A number of members have led services over the years. In the 1950s and 1960s Murray Stein, who owned a dress shop on Main Street, acted as the lay leader. The temple dedication program identifies Stein as the “lay rabbi.” and he was even active in the local clergy association. Since his death in 1968, several other members have served as worship leaders.

Jack Cristil

Photo by Bill Aron.

Photo by Bill Aron.

While “the King” is certainly the most famous person from Tupelo, a number of well known Jews have roots in Tupelo as well. Most notable was sports announcer Jack Cristil, the voice of the Mississippi State Bulldogs for over 50 years. Born to Russian-Jewish immigrants in Memphis, Cristil called hundreds of football games and over a thousand basketball games during his career. Known for his simple, smooth style and crisp one-liners, Cristil amassed great popularity and numerous awards. With phrases such as “colder than a pawnbroker’s heart,” this Mississippi legend did it all, from leading services at the local synagogue to interviewing Elvis Presley himself.

The Jewish Community in Tupelo Today

While an estimated 120 Jews lived in Tupelo the 1960s, that number declined in the late 20th century. Tupelo itself has flourished over the last 50 years, however. The city’s population doubled between 1960 and 2000, and the city gained national recognition as a model for economic growth and community development. A hundred years earlier, that growth likely would have made the local Jewish community one of the most vibrant in the state, but Tupelo came into its own as small-town Jewish business owners began to dwindle. Most of the sons and daughters of Tupelo's 20th-century Jewish shopkeepers went to college, became professionals, and settled in larger cities, so the Jewish population has not grown as a result of Tupelo’s economic rise.

Nevertheless, B’nai Israel remains active in the early 21st century. As of 2022, members include nine households in Tupelo and another eleven in nearby towns. An additional 15 long-distance members continue to support the congregation although they have moved away. Congregants meet weekly for lay-led services, including a bagel breakfast and shabbat morning service on the first Saturday of the month.

Nevertheless, B’nai Israel remains active in the early 21st century. As of 2022, members include nine households in Tupelo and another eleven in nearby towns. An additional 15 long-distance members continue to support the congregation although they have moved away. Congregants meet weekly for lay-led services, including a bagel breakfast and shabbat morning service on the first Saturday of the month.