Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Greenwood, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Greenwood

Overview

|

Greenwood, Mississippi, sits at the junction of the Yalobusha and Tallahatchie Rivers, which join there to form the Yazoo River. The town serves as the seat of Leflore County and a commercial and political hub for nearby Delta communities. To the east, Loess Bluffs separate the alluvial floodplains of the Delta from the rolling hills of Carroll County. The area attracted increasing numbers of Euro-American settlers after the Choctaw Nation ceded territory under the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in 1831, and those settlers imported a large population of enslaved Black workers in the following decades.

Although a few Jewish peddlers and merchants lived in or near Greenwood prior to the Civil War, a Jewish community did not take root in Greenwood until the late 19th century, when landowners cleared forests from large swaths of the Delta in order to grow cotton in its remarkably fertile soil. In the early 20th century, more Jews lived in the Delta than in any other part of Mississippi, and Greenwood became home to a Reform and an Orthodox congregation. Ahavath Rayim, the historically Orthodox congregation, stands out in Mississippi for its members’ long dedication to traditional practices. While Greenwood’s Jewish population dwindled in the late 20th century, Ahavath Rayim continues to hold High Holiday services as of the early 2020s. |

RESOURCES

Jewish Cemetery List |

Early Jewish Settlers

Stained glass windows at Ahavath Rayim synagogue.

Stained glass windows at Ahavath Rayim synagogue.

The first known Jews in the Greenwood area were Benjamin and Nancy (Levy) Gerson, natives of the German territories who moved from New Orleans to southern Carroll County (which then included Greenwood) in the late 1840s. Benjamin ran a general merchandise business in Greenwood, which had incorporated just seven years earlier. According to the 1850 Slave Schedule of the U.S. Census, the Gerson family enslaved two Black people, a 24-year-old woman and a 14-year-old girl. This was common for established Jewish merchants in the mid-19th-century South, and it indicates thay they accepted southern slavery as a practice and had attained a moderate level of wealth. Nancy Gerson gave birth to four children in Mississippi before the family returned to New Orleans in 1854.

Like other Delta communities, Greenwood developed modestly through the early 1870s, in part due to the disruption of the recent Civil War. In 1873 the town was home to three drygoods stores, two of which were Jewish-owned. Mark Stein ran one store while Henry Selinnger ran the other. Sellinger’s son E. S. Sellinger later became assistant police chief in Greenwood. That small Jewish population soon expanded as Greenwood and other Delta towns entered a period of rapid growth.

Like other Delta communities, Greenwood developed modestly through the early 1870s, in part due to the disruption of the recent Civil War. In 1873 the town was home to three drygoods stores, two of which were Jewish-owned. Mark Stein ran one store while Henry Selinnger ran the other. Sellinger’s son E. S. Sellinger later became assistant police chief in Greenwood. That small Jewish population soon expanded as Greenwood and other Delta towns entered a period of rapid growth.

Economic Growth and an Emerging Jewish Community

The Delta’s Jewish development accelerated in the late 19th century, and it resulted from both a general population boom and also the Delta’s emergence as the premier cotton growing region in the country. When the State of Mississippi created Leflore County during Reconstruction, Greenwood became the County Seat. The 1880 U.S. Census—the first to include the new county—reported 10,246 residents, 78% of whom were Black. The overall population of Leflore County doubled by the turn of the century, especially due to the migration of Black farmers who sought to make a better living in the booming cotton economy. In 1900 the county was home to nearly 24,000 citizens, fewer than 3,000 of whom were white. While Black labor raised and harvested Delta cotton, however, 95% of local Black farmers worked as sharecroppers or tenant farmers at the turn of the century.

As the local population grew during the late 19th century, new Jewish arrivals found their way to Greenwood and Leflore County. Men usually worked as peddlers or merchants. Some migrated with their families; others established themselves in town and later married a Jewish woman from elsewhere. Additionally, community histories tend to emphasize the stories of those Jews who made a long term home in Greenwood, but a number of Jewish merchants came and went during the period, which was characteristic of the United States’ highly mobile Jewish population.

The 1880 U.S. Census counted 84 immigrants in the county, including several Eastern European Jews. Phillip Cohen, for example, was a Russian-born “huckster” who lived in McNutt, a short distance northwest of Greenwood. Around the same time, Greenwood itself was home to jeweler Charles Stein and the Ettinger and Aron families. By 1884 a sufficient number of Jews had arrived that the local Valley Flag newspaper reported, “the Jewish New Year and Day of Atonement were duly observed here by our Hebrew Friends.” Jewish settlement only increased following the arrival of the railroad in 1886, and although a devastating 1890 fire disrupted business, the town quickly rebuilt itself.

In the 1890s Greenwood Jews continued to hold religious services in private homes and possibly rented spaces. Jewish men founded a local chapter of B’nai B’rith, a national Jewish fraternal order, in 1894. The first formally organized Jewish group in town, it was originally named for Marks Stein, the early Jewish settler, and later renamed for Albert Weiler, a prominent jeweler and local Jewish leader in the early 20th century. Jewish women also organized in the 1890s. A Hebrew Ladies Sewing Society formed in 1898 and served as a precursor for the local Ladies’ Aid Society and, eventually, the Temple Sisterhood of Greenwood’s Reform congregation.

As the local population grew during the late 19th century, new Jewish arrivals found their way to Greenwood and Leflore County. Men usually worked as peddlers or merchants. Some migrated with their families; others established themselves in town and later married a Jewish woman from elsewhere. Additionally, community histories tend to emphasize the stories of those Jews who made a long term home in Greenwood, but a number of Jewish merchants came and went during the period, which was characteristic of the United States’ highly mobile Jewish population.

The 1880 U.S. Census counted 84 immigrants in the county, including several Eastern European Jews. Phillip Cohen, for example, was a Russian-born “huckster” who lived in McNutt, a short distance northwest of Greenwood. Around the same time, Greenwood itself was home to jeweler Charles Stein and the Ettinger and Aron families. By 1884 a sufficient number of Jews had arrived that the local Valley Flag newspaper reported, “the Jewish New Year and Day of Atonement were duly observed here by our Hebrew Friends.” Jewish settlement only increased following the arrival of the railroad in 1886, and although a devastating 1890 fire disrupted business, the town quickly rebuilt itself.

In the 1890s Greenwood Jews continued to hold religious services in private homes and possibly rented spaces. Jewish men founded a local chapter of B’nai B’rith, a national Jewish fraternal order, in 1894. The first formally organized Jewish group in town, it was originally named for Marks Stein, the early Jewish settler, and later renamed for Albert Weiler, a prominent jeweler and local Jewish leader in the early 20th century. Jewish women also organized in the 1890s. A Hebrew Ladies Sewing Society formed in 1898 and served as a precursor for the local Ladies’ Aid Society and, eventually, the Temple Sisterhood of Greenwood’s Reform congregation.

Founding Congregations

As Greenwood continued to grow, local Jews established formal religious institutions. On October 6th, 1897 C.I. Stein hosted a meeting to discuss the possibility of forming a congregation. The attendees voted to do so, and they elected a board that included Albert Aron, president; L. Bernstein, vice president; C.I. Stein, secretary; and Ed Hyman, treasurer. Member families paid 50 cents each month for dues during the congregation’s first year.

The congregation took the name Beth Israel. In 1902 they purchased the old Episcopal Church of the Nativity on Main Street and converted it into a synagogue. Two years later Beth Israel joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the national organization of Reform Judaism. Most Mississippi congregations belonged to the Reform movement; not only did Jewish migrants find it difficult to maintain traditional practices in the rural South, but the relative lack of Jewish resources also dissuaded many traditionally observant Jews from moving there. Greenwood was home to a number of traditionalists, however, who split off and soon formed their own congregation.

That Orthodox group—the precursor to Greenwood’s historically Orthodox congregation, Ahavath Rayim—was established in 1907. Of the sixteen men who founded the congregation, all but one were foreign born, and the majority had emigrated from the Russian Empire after 1900. The male membership consisted of young shopkeepers who concentrated in typical Jewish commercial trades: dry goods, shoes, general merchandise, or groceries. They and their (primarily young) families preferred to maintain customary dietary restrictions (kashrut) and to follow traditional Hebrew liturgy for daily prayers and holiday observances. For the most part, they did not seek to participate in the social life of the white, Christian community, but they did send their children to the public schools. A congregational history indicates that the group purchased a cemetery on Bowie Lane around the time of its founding.

While the Orthodox congregation initially rented space in the Masonic Hall for their religious services, Beth Israel continued to worship in their Main Street synagogue until 1912, when a fire destroyed the building. Beth Israel members considered a merger with the Orthodox congregation after the loss of their building, but neither group wished to compromise their ritual practices to the extent that would have been necessary. Newspaper records suggest that Beth Israel became less active following the fire, but a visiting rabbi from Greenville, helped to reorganize the congregation in 1916. The group began to hold regular services again and started a religious school.

The congregation took the name Beth Israel. In 1902 they purchased the old Episcopal Church of the Nativity on Main Street and converted it into a synagogue. Two years later Beth Israel joined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the national organization of Reform Judaism. Most Mississippi congregations belonged to the Reform movement; not only did Jewish migrants find it difficult to maintain traditional practices in the rural South, but the relative lack of Jewish resources also dissuaded many traditionally observant Jews from moving there. Greenwood was home to a number of traditionalists, however, who split off and soon formed their own congregation.

That Orthodox group—the precursor to Greenwood’s historically Orthodox congregation, Ahavath Rayim—was established in 1907. Of the sixteen men who founded the congregation, all but one were foreign born, and the majority had emigrated from the Russian Empire after 1900. The male membership consisted of young shopkeepers who concentrated in typical Jewish commercial trades: dry goods, shoes, general merchandise, or groceries. They and their (primarily young) families preferred to maintain customary dietary restrictions (kashrut) and to follow traditional Hebrew liturgy for daily prayers and holiday observances. For the most part, they did not seek to participate in the social life of the white, Christian community, but they did send their children to the public schools. A congregational history indicates that the group purchased a cemetery on Bowie Lane around the time of its founding.

While the Orthodox congregation initially rented space in the Masonic Hall for their religious services, Beth Israel continued to worship in their Main Street synagogue until 1912, when a fire destroyed the building. Beth Israel members considered a merger with the Orthodox congregation after the loss of their building, but neither group wished to compromise their ritual practices to the extent that would have been necessary. Newspaper records suggest that Beth Israel became less active following the fire, but a visiting rabbi from Greenville, helped to reorganize the congregation in 1916. The group began to hold regular services again and started a religious school.

In 1917 Beth Israel built a temple on the corner of West Washington and Williamson Streets. Albert Weiler served as congregation president. The new brick building featured stained-glass windows, a new pipe organ, and two Torah scrolls in its ark. The 1917 dedication ceremony attracted prominent southern rabbis as well as a number of white Christian ministers from Greenwood. The reinvigoration of the late 1910s also influenced the activities of local Reform Jewish women, who transformed their Ladies’ Aid Society into a nationally affiliated Temple Sisterhood. In 1921 Beth Israel claimed 30 member families, and the congregation—whose denominational affiliation had lapsed—rejoined the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

Greenwood’s Orthodox congregation also became larger and more established during the 1910s and 1920s. From 1914 to 1923, Rabbi David Schapperstein served as the congregation’s first professional spiritual leader. During the congregation’s early history, members handled many of the day-to-day synagogue activities, including leading services and teaching classes for children; their rabbis concerned themselves largely with overseeing standards of kashrut in the community. Because most members had to open their businesses on Saturdays, weekly services took place on Friday nights. For Jewish education, adults studied Torah in each others’ homes. Congregational histories refer to children’s afternoon Hebrew classes as cheder, a term that denotes the traditional Hebrew instruction given to Jewish boys in Eastern Europe. Children from Orthodox families also attended Sunday School at Beth Israel, and women from the Orthodox community sometimes belonged to the Temple Sisterhood. The Reform Sunday School enrolled boys and girls under the oversight of Rabbi Mendel Silver of New Orleans, who visited monthly.

Greenwood’s Orthodox congregation also became larger and more established during the 1910s and 1920s. From 1914 to 1923, Rabbi David Schapperstein served as the congregation’s first professional spiritual leader. During the congregation’s early history, members handled many of the day-to-day synagogue activities, including leading services and teaching classes for children; their rabbis concerned themselves largely with overseeing standards of kashrut in the community. Because most members had to open their businesses on Saturdays, weekly services took place on Friday nights. For Jewish education, adults studied Torah in each others’ homes. Congregational histories refer to children’s afternoon Hebrew classes as cheder, a term that denotes the traditional Hebrew instruction given to Jewish boys in Eastern Europe. Children from Orthodox families also attended Sunday School at Beth Israel, and women from the Orthodox community sometimes belonged to the Temple Sisterhood. The Reform Sunday School enrolled boys and girls under the oversight of Rabbi Mendel Silver of New Orleans, who visited monthly.

In 1917 the Orthodox congregation received an official charter from the State of Mississippi and affiliated with the Orthodox Union, the primary denominational body of Orthodox congregations in the United States. That affiliation was not permanent, and the congregation has joined and left the Orthodox Union more than once during its history. Newspaper articles from the 1910s refer to the group as the Orthodox Congregation of Greenwood, and the name Ahavath Rayim does not appear in the local paper until 1936. In 1919 the congregation claimed about 35 member families and began the process of constructing a synagogue at George and Market Streets. They dedicated a new brick building in 1923. The synagogue cost approximately $35,000 to construct and the bimah (raised platform for leading services and chanting Torah) originally sat in the middle of the sanctuary, in the fashion of traditional European synagogues.

Civic and Business Life

In addition to B’nai B’rith and Jewish women’s organizations, Greenwood Jews participated in a variety of non-Jewish fraternal, civic, and cultural groups over the years. The Lions Club, Kiwanis, Rotary Club, Elks, and Masons all welcomed multiple Jewish members. Jewish families also participated in Greenwood Little Theater, the Community Concert Association, the Chamber of Commerce, and local country clubs. Although Jewish participation in such organizations indicated a level of acceptance in white, Christian society. At the same time, Greenwood Jews did face some social stigma; Leslie Kornfeld, who was born in Greenwood in 1912, later reported hearing anti-Jewish comments from non-Jewish peers as a child. However, he received more respect in high school—partly through participation on the basketball and track teams. According to Kornfeld, “you had a label on you in the old days, but that’s been torn off.”

A number of Jewish businesses prospered in Greenwood during the early 20th century. The city’s population grew from 3,000 people in 1900 to more than 14,000 in 1940, which provided a strong customer base for the many Jewish families who made their livings in retail trades. J. Kantor, who arrived from New York in 1896, set up a clothing store on East Market Street. When his business, “J. Kantor’s,” celebrated its 45th anniversary in 1942, the local paper noted that Kantor—“outfitter to mankind”—had “served with distinction as a member of the City Council, school board and other civic organizations” and that his retail success had allowed him to purchase farmland as well. While J. Kantor’s and Weiler Jewelry Store had developed into local institutions, other Jewish-owned businesses got their starts in later decades. Goldberg’s Shoes and Kornfeld’s Department Store (later known as Kornfeld’s Inc.) both started in the early 1920s. Both families belonged to Ahavath Rayim, and the stores remain open as of 2022.

A number of Jewish businesses prospered in Greenwood during the early 20th century. The city’s population grew from 3,000 people in 1900 to more than 14,000 in 1940, which provided a strong customer base for the many Jewish families who made their livings in retail trades. J. Kantor, who arrived from New York in 1896, set up a clothing store on East Market Street. When his business, “J. Kantor’s,” celebrated its 45th anniversary in 1942, the local paper noted that Kantor—“outfitter to mankind”—had “served with distinction as a member of the City Council, school board and other civic organizations” and that his retail success had allowed him to purchase farmland as well. While J. Kantor’s and Weiler Jewelry Store had developed into local institutions, other Jewish-owned businesses got their starts in later decades. Goldberg’s Shoes and Kornfeld’s Department Store (later known as Kornfeld’s Inc.) both started in the early 1920s. Both families belonged to Ahavath Rayim, and the stores remain open as of 2022.

Greenwood reached a population of 8,000 individuals around 1930 and continued to serve as the commercial hub for the local cotton-based economy. Despite the ups and downs of international cotton prices, Delta landowners remained committed to cotton monoculture, which left the Mississippi economy in a precarious state even before the arrival of the Great Depression in 1929. Many of Greenwood’s Jewish-owned retail establishments and other businesses persisted during the 1930s, but sharecropper evictions, Black migration to the urban North, and the eventual automation of the cotton harvest all led to decreases in the customer base for many Jewish-owned stores. As a result, Greenwood’s Jewish population probably peaked at more than 300 individuals in or around the late 1930s. While the conditions that caused Jewish Greenwood to shrink were established by the end of the 1940s, however, the decline was not immediately visible; .

During the 1940s Beth Israel remained active under the leadership of lay members and visiting rabbis, and the congregation’s practices adhered more closely to Classical Reform Judaism than ever before. At the same time, Zionism became increasingly influential in the local Jewish community. While many Reform Jews objected to political Zionism on the grounds that American Jews should not show loyalty to any country other than the United States, the idea of a Jewish state in Palestine was more popular among Orthodox Jews. Following World War II and the foundation of the State of Israel, Reform Jews in Greenwood and other cities became more likely to support fundraising through Israel Bond Drives and other programs.

During the 1940s Beth Israel remained active under the leadership of lay members and visiting rabbis, and the congregation’s practices adhered more closely to Classical Reform Judaism than ever before. At the same time, Zionism became increasingly influential in the local Jewish community. While many Reform Jews objected to political Zionism on the grounds that American Jews should not show loyalty to any country other than the United States, the idea of a Jewish state in Palestine was more popular among Orthodox Jews. Following World War II and the foundation of the State of Israel, Reform Jews in Greenwood and other cities became more likely to support fundraising through Israel Bond Drives and other programs.

Jewish Life in Post-War Greenwood

At the end of World War II approximately 30 Jewish families lived in Greenwood. A memoir from 1946 notes that their were 24 Jewish store owners in town, along with two junk dealers, two cotton merchants, and the owner of a dry cleaning business. On Howard Street, shoppers could patronize Gelman’s Cafeteria, Bennett’s Men’s Store, The Trading Post, City Laundry, B&R Department Store, and Goldberg’s Shoe Store—all Jewish-owned.

1950 saw the arrival of two notable Jewish newcomers to Greenwood and Ahavath Rayim. The first, Rabbi Samuel Stone had received his ordination in Jerusalem and served as a small-town rabbi in Minnesota and Ohio. As the Orthodox congregation’s primarily foreign-born founders aged, a younger generation of congregants sought a rabbi who could provide a stronger presence on the pulpit and increase involvement among young families. Rabbi Stone fit the bill, and the congregation grew to more than two hundred individual members by the time that he departed Greenwood in 1960. In addition to Greenwood residents, the congregation drew families from a wide area that included Belzoni, Greenwood, Indianola, Ruleville, and Winona. The congregation also renovated and expanded its synagogue in 1951, adding a new kosher kitchen and auditorium, as well as a religious school building. They also closed their mikvah, (ritual bath) and may have adopted mixed-gender seating at that time. That year also marked the reorganization of Ahavath Rayim’s women’s group, the Synagogue Auxiliary, who raised money, organized holiday events, assisted the rabbi with religious school administration, and helped maintain the cemetery.

1950 saw the arrival of two notable Jewish newcomers to Greenwood and Ahavath Rayim. The first, Rabbi Samuel Stone had received his ordination in Jerusalem and served as a small-town rabbi in Minnesota and Ohio. As the Orthodox congregation’s primarily foreign-born founders aged, a younger generation of congregants sought a rabbi who could provide a stronger presence on the pulpit and increase involvement among young families. Rabbi Stone fit the bill, and the congregation grew to more than two hundred individual members by the time that he departed Greenwood in 1960. In addition to Greenwood residents, the congregation drew families from a wide area that included Belzoni, Greenwood, Indianola, Ruleville, and Winona. The congregation also renovated and expanded its synagogue in 1951, adding a new kosher kitchen and auditorium, as well as a religious school building. They also closed their mikvah, (ritual bath) and may have adopted mixed-gender seating at that time. That year also marked the reorganization of Ahavath Rayim’s women’s group, the Synagogue Auxiliary, who raised money, organized holiday events, assisted the rabbi with religious school administration, and helped maintain the cemetery.

The second important person to relocate to Greenwood in 1950 was Ilse Markus Goldberg, who married local store owner Ervin Goldberg. Ilse Goldberg had grown up in Germany during the 1930s. Nazi officials detained her father following Kristallnacht and sent him to Buchenwald concentration camp, but he was released five weeks later due to his military service during World War I. In 1939 the family managed to secure passage on a ship from Italy to Shanghai, China, which was occupied by Japan during the war. The Markus family lived there under trying conditions for eight years before gaining passage to the United States in 1947. They soon settled in Memphis, where Ilse met and married Ervin. In Greenwood the couple ran Goldberg’s Shoes and Sportswear and raised two sons, Mike and Jerome. They also belonged to Ahavath Rayim and maintained an observant home. Ilse kept a kosher kitchen, which required her to order frozen meat from St. Louis and Chicago, which she stored in multiple freezers. (In later years, the internet and readily available kosher meat in Memphis made the process much easier.) In recognition of Ilse Goldberg’s decades of dedication to family and communal life, the Greenwood Commonwealth newspaper named her Mother of the Year in 1993.

The 1950s brought about more modest growth for Beth Israel. The Reform congregation had claimed 30 member households in 1940 but expanded to 66 families by 1957. They also enrolled 20 students in religious school, and the Temple Sisterhood remained active. Beth Israel also drew members from outside Greenwood—including residents of Grenada, Indianola, and Winona—but it did not pull from as wide an area as Ahavath Rayim.

While the small Reform congregation kept up a range of activities during the 1950s, it also faced several challenges. By the end of the decade their synagogue building showed signs of structural defects. Rather than embark on an expensive remodeling project the congregation sold its building to the First Christian Church. They considered a merger with Ahavath Rayim, but the two synagogues failed to come to an agreement on how to blend their different traditions. In 1966 Congregational President Gerald Jacobs led the effort to secure a new synagogue on West President Street. By the following year, membership had declined to such an extent that Beth Israel dropped its Sunday school program.

The 1950s brought about more modest growth for Beth Israel. The Reform congregation had claimed 30 member households in 1940 but expanded to 66 families by 1957. They also enrolled 20 students in religious school, and the Temple Sisterhood remained active. Beth Israel also drew members from outside Greenwood—including residents of Grenada, Indianola, and Winona—but it did not pull from as wide an area as Ahavath Rayim.

While the small Reform congregation kept up a range of activities during the 1950s, it also faced several challenges. By the end of the decade their synagogue building showed signs of structural defects. Rather than embark on an expensive remodeling project the congregation sold its building to the First Christian Church. They considered a merger with Ahavath Rayim, but the two synagogues failed to come to an agreement on how to blend their different traditions. In 1966 Congregational President Gerald Jacobs led the effort to secure a new synagogue on West President Street. By the following year, membership had declined to such an extent that Beth Israel dropped its Sunday school program.

A Shrinking Jewish Community

By 1960 the population of Leflore County had begun to shrink, and Greenwood itself reached its peak population around 1970. In the years after World War II, younger Jews became increasingly likely to attend college and move to larger cities. At the same time, population loss, a struggling agricultural economy, and competition from new chain retailers challenged the viability of many local Jewish businesses. The Jewish population of Greenwood fell to around 200 people in the 1970s and declined precipitously over the next two decades. Beth Israel’s Temple Sisterhood claimed only six members in 1960, and the group formally disbanded in 1970. The local B’nai B’rith chapter had grown to 63 members in 1955, but membership decreased to fewer than 30 men in the 1970s.

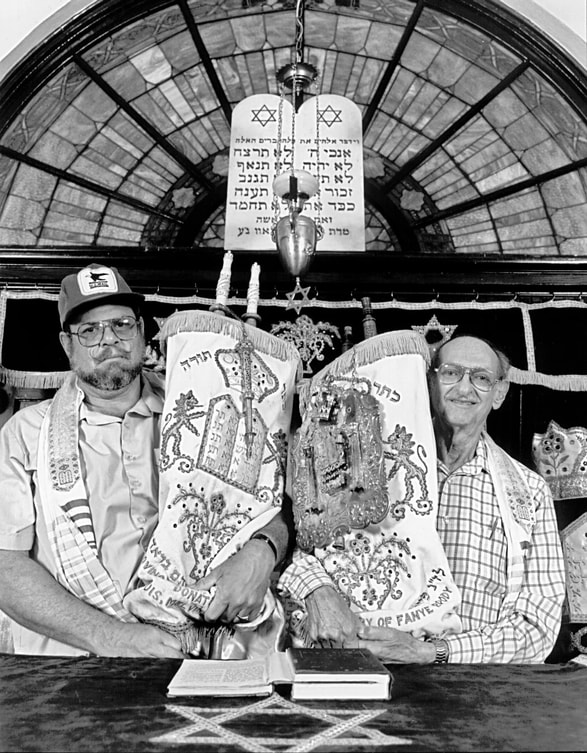

Joe Martin Erber with his uncle Meyer Gelman. Bill Aron, c. 1990.

Joe Martin Erber with his uncle Meyer Gelman. Bill Aron, c. 1990.

Beth Israel continued to hold services into the 1980s. Student rabbis from Hebrew Union College led High Holiday services, as they had done for decades.The congregation ceased to operate and sold its building in 1989.

Ahavath Rayim employed rabbis for short periods during the 1960s but relied primarily on lay leaders by 1970. Membership declined to 65 individuals with only five students in religious school. In 1976 Memphis Rabbi Benjamin Wolmark took an interest in Ahavath Rayim and began making bimonthly visits to Greenwood to teach religious school and perform religious ceremonies. Leslie Kornfeld served as congregational president during much of this period. Lay leaders continued to conduct Shabbat services on Friday nights; Joe Martin Erber, who served as lay leader for much of the 1980s and 1990s, became a central figure in journalistic profiles of the small congregation, and he appeared in a documentary film and widely circulated photographs. By the late 1980s the congregation often failed to draw a minyan—a quorum of ten people, traditionally men. Rabbi Wolmark continued to visit regularly until the mid-1990s, and the congregation shifted to monthly, rather than weekly, Friday night services.

In the early 21st century, Ahavath Rayim persisted as a small, lay-led congregation, even as some of its practices became less Orthodox. Sometime around 2005, Joe Martin Erber stopped Friday night and High Holiday services due to ill health; he died in 2013. At that point, Nashville resident Steve Hirsch (father-in-law of Ilse Goldberg’s grandson Ricky Goldberg) took over Hebrew prayers for Rosh Hashanah services, which drew additional participants from Jackson, Mississippi; Memphis, Tennessee; and beyond. The Hirsch family also donated a set of Conservative machzors (High Holiday prayer books) to the congregation. Reform services have also taken place in Ahavath Rayim under the leadership of Rabbi Micah Greenstein of Temple Israel, Memphis. As of 2022 only a handful of Jews live in Greenwood and nearby towns, and most of them belong to the Goldberg family. Still, there are no plans to dissolve Ahavath Rayim, which will mark a century in its current synagogue in 2023.

Ahavath Rayim employed rabbis for short periods during the 1960s but relied primarily on lay leaders by 1970. Membership declined to 65 individuals with only five students in religious school. In 1976 Memphis Rabbi Benjamin Wolmark took an interest in Ahavath Rayim and began making bimonthly visits to Greenwood to teach religious school and perform religious ceremonies. Leslie Kornfeld served as congregational president during much of this period. Lay leaders continued to conduct Shabbat services on Friday nights; Joe Martin Erber, who served as lay leader for much of the 1980s and 1990s, became a central figure in journalistic profiles of the small congregation, and he appeared in a documentary film and widely circulated photographs. By the late 1980s the congregation often failed to draw a minyan—a quorum of ten people, traditionally men. Rabbi Wolmark continued to visit regularly until the mid-1990s, and the congregation shifted to monthly, rather than weekly, Friday night services.

In the early 21st century, Ahavath Rayim persisted as a small, lay-led congregation, even as some of its practices became less Orthodox. Sometime around 2005, Joe Martin Erber stopped Friday night and High Holiday services due to ill health; he died in 2013. At that point, Nashville resident Steve Hirsch (father-in-law of Ilse Goldberg’s grandson Ricky Goldberg) took over Hebrew prayers for Rosh Hashanah services, which drew additional participants from Jackson, Mississippi; Memphis, Tennessee; and beyond. The Hirsch family also donated a set of Conservative machzors (High Holiday prayer books) to the congregation. Reform services have also taken place in Ahavath Rayim under the leadership of Rabbi Micah Greenstein of Temple Israel, Memphis. As of 2022 only a handful of Jews live in Greenwood and nearby towns, and most of them belong to the Goldberg family. Still, there are no plans to dissolve Ahavath Rayim, which will mark a century in its current synagogue in 2023.

Updated June 2022

Selected Bibliography

Ahavath Rayim Congregational History, c. 1976.

Annie Hughes Dixon, "History of Jewish Chruches Is Begun," The Morning Star (Greenwood), 28 June 1951.

David Isay, “Mississippi Jews,” All Things Considered, National Public Radio, 20 Dec. 1991.

Ahavath Rayim Congregational History, c. 1976.

Annie Hughes Dixon, "History of Jewish Chruches Is Begun," The Morning Star (Greenwood), 28 June 1951.

David Isay, “Mississippi Jews,” All Things Considered, National Public Radio, 20 Dec. 1991.