Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Laurel, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Laurel

Overview

|

Jews first came to Laurel, Mississippi, in the 1890s, not long after the town was founded in Mississippi’s Piney Woods (also known as the Pine Belt). It became a regional center for the timber industry as the railroad connected the yellow pine forests of Mississippi to national and international markets. By the turn of the 20th century, Laurel milled and shipped more yellow pine wood than any other town in America. This economic boom drew Jewish settlers to Laurel and Jones County, and they opened stores catering to local timber workers and their families. In 1900 there were nine Jews in Laurel, precursors to a small but vibrant community that lasted for several decades. Local Jews soon formed a congregation and built a synagogue in 1907. The Jewish population of Laurel peaked in the 1930s, and the community remained active into the 1960s.

Beginning in 2016, the HGTV program Home Town introduced Laurel and its historic residential neighborhoods to a national audience, but by that point only one Jewish resident lived in town. |

RESOURCES

Jewish Cemetery List |

Establishing a Jewish Community

Laurel attracted a small number of Jews by the end of the nineteenth century, but these first Jewish residents seem to have been transient. None of the eventual founders of the town’s Jewish congregation appear in local census records before 1910, and available sources only name one Laurel Jew who arrived before 1900—Joe Kastleman, an immigrant from the Russian Empire who started a business on Front Street in 1899. Kastleman started his business with “a small stock of goods” in a 200-square-foot rented space. By 1905 his brother Jake had joined him in Laurel, and the Kastleman Brothers store, which sold dry goods and clothing, occupied two brick buildings.

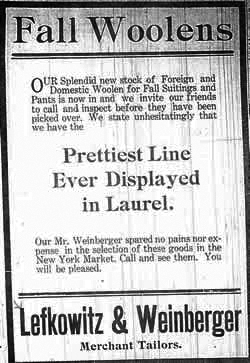

As new Jewish residents established businesses in Laurel in the first decade of the 20th century, they formed the nucleus of a Jewish community. Pincus Lefkowitz and his son-in-law Nathan Weinberger established a menswear and tailoring business, Lefkowitz and Weinberger, around 1905. Both men and their wives—Sarah Lefkowitz and Jennie Lefkowitz Weinberger—were born in Czech territory in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Nathan and Sarah Weinberger were married in Meridian in 1900, where the families lived before relocating to Laurel. Lefkowitz and Weinberger typified the Laurel Jewish community, which consisted primarily of immigrant Jews from Central and Eastern Europe who made their livings in dry goods, clothing, or related retail fields. Additionally, the families’ connections to Meridian, where they had relatives, reflected the Laurel Jewish community’s early links to the larger city. Laurel Jews traveled to Meridian for religious services before founding their own congregation, and they later relied on Meridian rabbis for occasional religious leadership.

Laurel Jews established a religious community fairly quickly. They first held their own religious services in 1901 and obtained a Torah in 1903. In 1906 they received a charter for Knesseth Israel Congregation, and Pincus Lefkowitz served as the first president. The other founding officers were B. B. Pollack, Abraham Marcus, Nathan Weinberger, and Jake Kastleman. The congregation, which kept its records in Yiddish, met in members' homes until they built a synagogue. When they dedicated their first synagogue building in September 1907, the ceremony included rabbis from Meridian and Selma, as well as reverends from local Episcopal and Presbyterian churches. The participation of Christian clergy was especially fitting given the high level of support for the building project from local non-Jews, who reportedly donated a majority of the necessary funds.

As new Jewish residents established businesses in Laurel in the first decade of the 20th century, they formed the nucleus of a Jewish community. Pincus Lefkowitz and his son-in-law Nathan Weinberger established a menswear and tailoring business, Lefkowitz and Weinberger, around 1905. Both men and their wives—Sarah Lefkowitz and Jennie Lefkowitz Weinberger—were born in Czech territory in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Nathan and Sarah Weinberger were married in Meridian in 1900, where the families lived before relocating to Laurel. Lefkowitz and Weinberger typified the Laurel Jewish community, which consisted primarily of immigrant Jews from Central and Eastern Europe who made their livings in dry goods, clothing, or related retail fields. Additionally, the families’ connections to Meridian, where they had relatives, reflected the Laurel Jewish community’s early links to the larger city. Laurel Jews traveled to Meridian for religious services before founding their own congregation, and they later relied on Meridian rabbis for occasional religious leadership.

Laurel Jews established a religious community fairly quickly. They first held their own religious services in 1901 and obtained a Torah in 1903. In 1906 they received a charter for Knesseth Israel Congregation, and Pincus Lefkowitz served as the first president. The other founding officers were B. B. Pollack, Abraham Marcus, Nathan Weinberger, and Jake Kastleman. The congregation, which kept its records in Yiddish, met in members' homes until they built a synagogue. When they dedicated their first synagogue building in September 1907, the ceremony included rabbis from Meridian and Selma, as well as reverends from local Episcopal and Presbyterian churches. The participation of Christian clergy was especially fitting given the high level of support for the building project from local non-Jews, who reportedly donated a majority of the necessary funds.

Jewish Life in Laurel

Local Jews continued to build Jewish institutions after the construction of the Knesseth Israel synagogue. In 1908 they established a local chapter of B’nai B’rith, a popular Jewish fraternal organization, with assistance from Herman Katz of Hattiesburg. The congregation founded a religious school the same year. The Jewish community continued to grow during the 1910s, and Jewish women founded the Knesseth Israel Sisterhood in 1915 with 25 members. The group’s first officials were Sarah Jacobs, Jennie Weinberger, Effie Scharff, and Rose Katz. In 1917 the congregation purchased land for Knesseth Israel Cemetery.

In 1927 Knesseth Israel reached an agreement with a hotel developer to exchange its synagogue building and the surrounding lot for a new piece of land on Fifth Avenue and Eighth Street. The congregation did not complete the new synagogue until 1931, when they moved into a small brick building. Laurel Jews intended for their modest synagogue to be a placeholder, which would serve as an educational building when they were able to construct a more substantial synagogue. That opportunity never arose, however, and the congregation used the second building for the rest of its existence. Laurel’s Jewish population, which peaked in the late 1920s, stood at 65 individuals in 1937, and it continued to decline in subsequent years.

At its outset, Knesseth Israel followed Orthodox customs. By the 1930s, however, two factions had developed within the congregation: one group that wanted to maintain traditional observances and another that wished to adopt Reform practices. According to a 1931 source, there was not a clear majority for either side, which resulted in a stalemate. By 1940, however, the Reform contingent won out, and the congregation affiliated with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

The small Jewish community of Laurel never employed a full-time rabbi. Instead, they held lay-led services, hosted visiting rabbis from nearby towns, or hired rabbinical students from Hebrew Union College. Initially, they sought the services of rabbis from Meridian. As the Jewish population in nearby Hattiesburg increased, Knesseth Israel entered into an agreement with Hattiesburg’s Temple B’nai Israel that brought the larger congregation’s rabbi to Laurel to lead services on a monthly basis.

In 1927 Knesseth Israel reached an agreement with a hotel developer to exchange its synagogue building and the surrounding lot for a new piece of land on Fifth Avenue and Eighth Street. The congregation did not complete the new synagogue until 1931, when they moved into a small brick building. Laurel Jews intended for their modest synagogue to be a placeholder, which would serve as an educational building when they were able to construct a more substantial synagogue. That opportunity never arose, however, and the congregation used the second building for the rest of its existence. Laurel’s Jewish population, which peaked in the late 1920s, stood at 65 individuals in 1937, and it continued to decline in subsequent years.

At its outset, Knesseth Israel followed Orthodox customs. By the 1930s, however, two factions had developed within the congregation: one group that wanted to maintain traditional observances and another that wished to adopt Reform practices. According to a 1931 source, there was not a clear majority for either side, which resulted in a stalemate. By 1940, however, the Reform contingent won out, and the congregation affiliated with the Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

The small Jewish community of Laurel never employed a full-time rabbi. Instead, they held lay-led services, hosted visiting rabbis from nearby towns, or hired rabbinical students from Hebrew Union College. Initially, they sought the services of rabbis from Meridian. As the Jewish population in nearby Hattiesburg increased, Knesseth Israel entered into an agreement with Hattiesburg’s Temple B’nai Israel that brought the larger congregation’s rabbi to Laurel to lead services on a monthly basis.

Jewish Businesses and Civic Life

The outpouring of non-Jewish support for the construction of the 1907 synagogue reflected amicable relationships between Jews and their neighbors that persisted for the life of the Laurel Jewish community. Jewish business owners played a visible role in the town’s civic life, and local Jews reported a high degree of acceptance from the white, Christian majority. One local Jew wrote in 1931 that “the voice of the Jew was heard and respected as a worthy, capable, and good citizen.” In 1929 local non-Jews donated money to a relief fund for Jewish settlers in Palestine. The local newspaper offered explanations of the Jewish high holidays in the first year of Knesseth Israel’s existence and continued to cover Jewish lifecycle events for decades to come. In 1935, the Laurel Leader Call reported on the confirmation of William Henry Amber, Herbert Joseph, Rosemary Pellman, Irene Percoff, and Harold Maurice Matison. The service was officiated by Rabbi William Ackerman of Meridian, and the newspaper reported that a large crowd of both Jews and non-Jews attended to see the “impressive rites.”

Among the prominent Jewish-owned businesses was the Fine Brothers Store, which sold shoes, clothes, and other general goods for both men and women at affordable prices. The store was founded by Nathan, Louis, and Joe Fine. (Harry Fine joined the business later, but—despite his name—he was of no relation to the other three.) In the late 1920s the Fine Brothers Store brought on another partner, Dave Matison. The new business, Fine Bros.-Matison, operated stores in Laurel and Hattiesburg.

Jewish merchants were well known in the town and in wider Jewish circles. Dave Matison served as a regional B’nai B’rith officer and as a board member of the National Jewish Hospital in Denver, Colorado. The Laurel Morning Call reported on his hospital leadership and noted that he had once helped a non-Jewish Laurel woman receive tuberculosis treatment at the facility. In addition to garnering respect for their tailoring skills, Pincus Lefkowitz and Nathan Weinberger (of Lefkowitz and Weinberger) were popular figures, and Weinberger became known for teaching dance lessons to young Laurel socialites.

Despite the evidence of Jewish acculturation into and acceptance by white, Christian society, there were Laurel residents who harbored anti-Jewish views. In 1964 Laurel businessman Sam Bowers established a Ku Klux Klan splinter group known as the White Knights. Bowers and his closest associates promulgated Christian extremism and antisemitic conspiracy theories in addition to white supremacy, and the White Knights attracted thousands of members in Mississippi and beyond. The group carried out dozens of bombings and murders during the mid-to-late 1960s. While most of their victims were Black Mississippians, a White Knights terror cell targeted Jews in Jackson and Meridian in 1967 and 1968. Laurel’s Jewish population had begun to shrink long before Laurel became a hotbed for the revived Klan, and available evidence does not suggest that the group’s presence directly contributed to the waning of the Jewish community.

Jewish merchants were well known in the town and in wider Jewish circles. Dave Matison served as a regional B’nai B’rith officer and as a board member of the National Jewish Hospital in Denver, Colorado. The Laurel Morning Call reported on his hospital leadership and noted that he had once helped a non-Jewish Laurel woman receive tuberculosis treatment at the facility. In addition to garnering respect for their tailoring skills, Pincus Lefkowitz and Nathan Weinberger (of Lefkowitz and Weinberger) were popular figures, and Weinberger became known for teaching dance lessons to young Laurel socialites.

Despite the evidence of Jewish acculturation into and acceptance by white, Christian society, there were Laurel residents who harbored anti-Jewish views. In 1964 Laurel businessman Sam Bowers established a Ku Klux Klan splinter group known as the White Knights. Bowers and his closest associates promulgated Christian extremism and antisemitic conspiracy theories in addition to white supremacy, and the White Knights attracted thousands of members in Mississippi and beyond. The group carried out dozens of bombings and murders during the mid-to-late 1960s. While most of their victims were Black Mississippians, a White Knights terror cell targeted Jews in Jackson and Meridian in 1967 and 1968. Laurel’s Jewish population had begun to shrink long before Laurel became a hotbed for the revived Klan, and available evidence does not suggest that the group’s presence directly contributed to the waning of the Jewish community.

The Decline of the Laurel Jewish Community

At some point in the 1920s the membership of Knesseth Israel in Laurel reached 45 households, but that number fell precipitously by 1931, when a congregational history reported only 14 adult, male members. Nevertheless, the town proved a welcoming destination for a small contingent of Jewish families. Arthur Frohman, for example, moved to Laurel in 1936 to open Arthur’s Store for Men and raised a family in town. “Arthur’s,” as the store was known, catered to Black clientele from Laurel and the surrounding area. Over the years, it gained popularity for its layaway plans and because Arthur employed Black workers in the shop.

Laurel’s lumber-related economy remained strong in the immediate postwar era, but Jewish population decline persisted. Eventually the congregation was no longer able to pay for regular visits from out-of-town rabbis and relied on local lay leaders. Then, in the early morning of January 25th, 1969, a freight train loaded with liquid butane tankers derailed near the residential neighborhood where the synagogue was located. A chain of explosions ensued, which destroyed nearby buildings and shot flames and debris to homes and businesses as far as ten blocks away. The resulting fires destroyed 46 buildings and damaged 166 more. One person died. The affected buildings included the Knesseth Israel synagogue, which sustained significant damage. The congregation suspended services immediately and dissolved its assets in 1970. Two local African American Christian congregations collected building materials from the synagogue for use at their own churches.

When Knesseth Israel disbanded, it set up a trust for local charities that continued to operate for several decades. The congregation also donated a Torah scroll to the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, which was on permanent loan to the Institute of Southern Jewish Life as of 2021. For remaining Laurel Jews, Hattiesburg’s Temple B’nai Israel, approximately 30 miles away, provided opportunities for worship and community.

As the Jewish population of Laurel shrank, the former Jewish stores began to disappear. Arthur’s Store for Men was the last Jewish shop to close. Arthur Frohman ran the store for nearly sixty years before passing it on to his oldest son, Robert Frohman. When Robert died in 1996 his younger brother Harold took over, keeping the longtime Laurel establishment open until 2016. Harold, who described himself as the “last Jew in Laurel,” died in 2017. Little evidence remains of Laurel’s Jewish history outside the Knesseth Israel Cemetery, one of several sections in Hickory Grove Cemetery, where 58 burials (and 130 vacant plots) tell the story of local Jewish life.

Laurel’s lumber-related economy remained strong in the immediate postwar era, but Jewish population decline persisted. Eventually the congregation was no longer able to pay for regular visits from out-of-town rabbis and relied on local lay leaders. Then, in the early morning of January 25th, 1969, a freight train loaded with liquid butane tankers derailed near the residential neighborhood where the synagogue was located. A chain of explosions ensued, which destroyed nearby buildings and shot flames and debris to homes and businesses as far as ten blocks away. The resulting fires destroyed 46 buildings and damaged 166 more. One person died. The affected buildings included the Knesseth Israel synagogue, which sustained significant damage. The congregation suspended services immediately and dissolved its assets in 1970. Two local African American Christian congregations collected building materials from the synagogue for use at their own churches.

When Knesseth Israel disbanded, it set up a trust for local charities that continued to operate for several decades. The congregation also donated a Torah scroll to the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, which was on permanent loan to the Institute of Southern Jewish Life as of 2021. For remaining Laurel Jews, Hattiesburg’s Temple B’nai Israel, approximately 30 miles away, provided opportunities for worship and community.

As the Jewish population of Laurel shrank, the former Jewish stores began to disappear. Arthur’s Store for Men was the last Jewish shop to close. Arthur Frohman ran the store for nearly sixty years before passing it on to his oldest son, Robert Frohman. When Robert died in 1996 his younger brother Harold took over, keeping the longtime Laurel establishment open until 2016. Harold, who described himself as the “last Jew in Laurel,” died in 2017. Little evidence remains of Laurel’s Jewish history outside the Knesseth Israel Cemetery, one of several sections in Hickory Grove Cemetery, where 58 burials (and 130 vacant plots) tell the story of local Jewish life.

Selected Bibliography

Inventory of the Church and Synagogue Archives of Mississippi: Jewish Congregations and Organizations (Jackson: Mississippi State Conference of B'nai B'rith, 1940).

“First Jewish Services Held Here in 1901,” Leader-Call Centennial Edition, May 11, 1982.

David Marcus, “Historical aspect of the first thirty years of Laurel Jewry,” (1931) original manuscript at Jacob Rader Marcus American Jewish Archives.

Jack Nelson, Terror in the Night: the Klan'’s Campaign Against the Jews (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993).

Inventory of the Church and Synagogue Archives of Mississippi: Jewish Congregations and Organizations (Jackson: Mississippi State Conference of B'nai B'rith, 1940).

“First Jewish Services Held Here in 1901,” Leader-Call Centennial Edition, May 11, 1982.

David Marcus, “Historical aspect of the first thirty years of Laurel Jewry,” (1931) original manuscript at Jacob Rader Marcus American Jewish Archives.

Jack Nelson, Terror in the Night: the Klan'’s Campaign Against the Jews (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993).