Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Osyka, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Osyka

Overview

Osyka is a small town at the southern edge of Pike County, Mississippi, adjacent to the Louisiana border. The name comes from a Choctaw word meaning “soaring eagle.” Founded on a newly-built railroad line in 1854, Osyka became a local commercial hub due to the presence of a cotton gin and cotton warehouse. The lumber industry also operated in the area, where longleaf yellow pine provided timber as land was cleared for farming.

A number of Jewish families arrived in Osyka at the time of its founding, and a Jewish presence persisted until the early 20th century. Most local Jews had roots in Central Europe—particularly Alsace, Bavaria, and Prussia—and the first Osyka residents may have emigrated from Europe due to political and economic turmoil following the revolutions of 1848. Jewish Osyka residents never built a synagogue, but they did hold worship services and established a Jewish cemetery. That cemetery fell into disrepair by the mid-20th century but attracted renewed attention and some preservation efforts around the turn of the 21st century.

A number of Jewish families arrived in Osyka at the time of its founding, and a Jewish presence persisted until the early 20th century. Most local Jews had roots in Central Europe—particularly Alsace, Bavaria, and Prussia—and the first Osyka residents may have emigrated from Europe due to political and economic turmoil following the revolutions of 1848. Jewish Osyka residents never built a synagogue, but they did hold worship services and established a Jewish cemetery. That cemetery fell into disrepair by the mid-20th century but attracted renewed attention and some preservation efforts around the turn of the 21st century.

Early Settlers

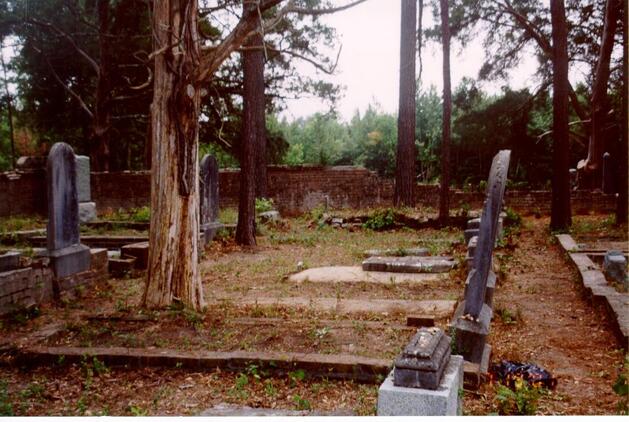

The Jewish section of the old German Cemetery in Osyka, 2001.

The Jewish section of the old German Cemetery in Osyka, 2001.

Osyka’s Jewish settlers set up businesses primarily as merchants, though some worked as clerks or horse traders and one local Jew was a wheelwright. Jews were involved with the city’s early development, and they contributed to the founding of a German school which also served the families of Christian German-speaking immigrants.

Alsatian immigrants Samuel and Lazar Wolf were among the first Jewish arrivals, and their families played important roles in the local community. In the 1860s Osyka Jews held religious services in the home of one of the brothers (probably Lazar). Sam Wolf became a cotton merchant, buying cotton from local farmers in order to send it south to New Orleans on the train. Two of his daughters, Fanny Wolf Frank and Delphine Wolf Keiffer, married men from prominent New Orleans Jewish families.

Despite their foreign origins, Jews were prominent members of the civic and social life of Osyka. They served as aldermen on the town council and in other important civic posts. In the 1880s, a group of Jews joined the local Masonic orders and Lions’ Club. On June 4, 1877, Meyer Wolf helped organize the Hancock Democratic Club of Osyka. In 1894, Jews were even involved at the First Baptist Church, as Leonard Cahn was featured in their production of Mordecai, a play relating to the Jewish holiday of Purim.

Alsatian immigrants Samuel and Lazar Wolf were among the first Jewish arrivals, and their families played important roles in the local community. In the 1860s Osyka Jews held religious services in the home of one of the brothers (probably Lazar). Sam Wolf became a cotton merchant, buying cotton from local farmers in order to send it south to New Orleans on the train. Two of his daughters, Fanny Wolf Frank and Delphine Wolf Keiffer, married men from prominent New Orleans Jewish families.

Despite their foreign origins, Jews were prominent members of the civic and social life of Osyka. They served as aldermen on the town council and in other important civic posts. In the 1880s, a group of Jews joined the local Masonic orders and Lions’ Club. On June 4, 1877, Meyer Wolf helped organize the Hancock Democratic Club of Osyka. In 1894, Jews were even involved at the First Baptist Church, as Leonard Cahn was featured in their production of Mordecai, a play relating to the Jewish holiday of Purim.

The Civil War and the Late 19th Century

As of 1860 Pike County’s population consisted of approximately 6,000 free white residents and nearly 5,000 enslaved African Americans. The local agricultural economy was much less dependent on cotton than it was in other areas of the state, and farmers grew rice, corn, and livestock, in addition to operating orchards. Of the known Jewish families in Osyka, Federal Census records do not reflect that any owned slaves, but family lore from descendants of Samuel Wolf indicates that his family may have enslaved a domestic worker.

During the Civil War, Osyka served as a Confederate agriculture center and weapons depot. As a result, the town was hit hard by Union attacks. In 1864 Brigadier General Albert L. Lee reported that his troops had “destroyed 4,000 pounds of bacon, 12 barrels of whiskey, 100 dozen boots and shoes, and [a] large quantity of corn and meal.” According to family stories, Federal troops also burned the cotton stored in Samuel Wolf’s warehouse.

During the Civil War, Osyka served as a Confederate agriculture center and weapons depot. As a result, the town was hit hard by Union attacks. In 1864 Brigadier General Albert L. Lee reported that his troops had “destroyed 4,000 pounds of bacon, 12 barrels of whiskey, 100 dozen boots and shoes, and [a] large quantity of corn and meal.” According to family stories, Federal troops also burned the cotton stored in Samuel Wolf’s warehouse.

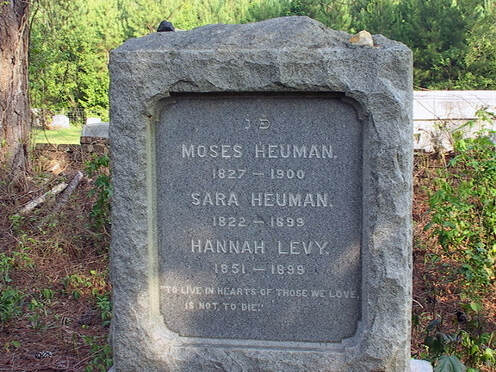

Gravestone of Moses Heuman, Sara Heuman, and Hannah Levy, 2001.

Gravestone of Moses Heuman, Sara Heuman, and Hannah Levy, 2001.

Following the turmoil of the war years, Jewish businesses prospered in the late 19th century. Jewish businesses belonging to the Wolfs and other families offered general merchandise, farm supplies, and larger items such as stoves and buggies. Max Heuman edited the local paper, the Osyka Herald. Lehman and Leopold opened a butcher shop which was known for ringing a bell to announce fresh deliveries; the bell had once signaled dinner time on a local plantation.

In addition to their connections to New Orleans, Jews in and around Osyka maintained family, social, and business links in cities and towns ranging from Summit (in northern Pike County) to Helena, Arkansas, and Cincinnati, Ohio. As a result, a number of late-19th century newspapers from the South and midwest list Jewish Osyka residents as guests at social functions and lifecycle events.

In 1878 Osyka suffered from an outbreak of yellow fever that afflicted much of the Gulf South. The disease killed several Jewish residents, including two sons of Samuel and Henriette Wolf: Henry (age 5) and Myer (age 21). Adolph Kahn also died from the epidemic; his widow and children returned to Germany, and some of their descendants fled from there to British Palestine in 1933. It seems that these yellow fever deaths prompted local Jews to establish their own section (surrounded by a customary wall) in a cemetery that other German immigrants had established in the 1860s. From 1878 to the early 20th century, more than two dozen Jewish burials took place at the site.

In addition to their connections to New Orleans, Jews in and around Osyka maintained family, social, and business links in cities and towns ranging from Summit (in northern Pike County) to Helena, Arkansas, and Cincinnati, Ohio. As a result, a number of late-19th century newspapers from the South and midwest list Jewish Osyka residents as guests at social functions and lifecycle events.

In 1878 Osyka suffered from an outbreak of yellow fever that afflicted much of the Gulf South. The disease killed several Jewish residents, including two sons of Samuel and Henriette Wolf: Henry (age 5) and Myer (age 21). Adolph Kahn also died from the epidemic; his widow and children returned to Germany, and some of their descendants fled from there to British Palestine in 1933. It seems that these yellow fever deaths prompted local Jews to establish their own section (surrounded by a customary wall) in a cemetery that other German immigrants had established in the 1860s. From 1878 to the early 20th century, more than two dozen Jewish burials took place at the site.

The End of Jewish Osyka

The 1878 yellow fever epidemic caused setbacks for Osyka and surrounding towns, and additional events—including the extension of the railroad, the exhaustion of nearby timber resources, and the decline of the cotton crop—hurt the local economy in subsequent decades. A number of local Jewish families departed for Baton Rouge and New Orleans around the turn of the twentieth century, although some Jewish businesses persisted into the 1910s. In the absence of an active Jewish community, the Jewish cemetery section fell into disuse and eventually disrepair.

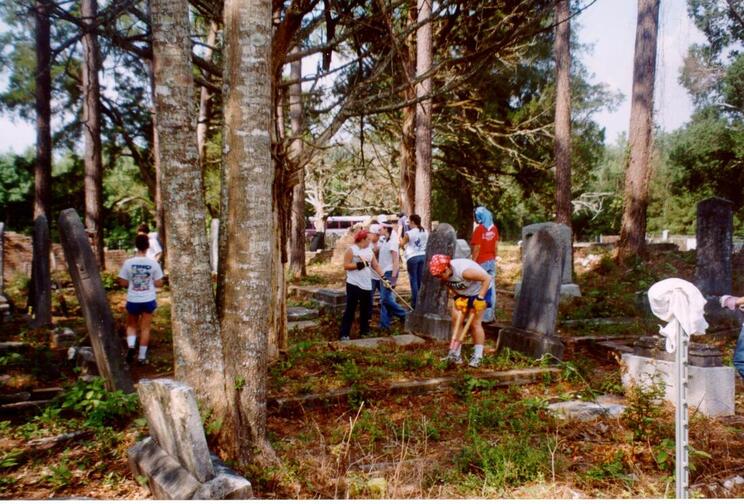

The cemetery gained the attention of local, non-Jewish residents in the 1970s. Lynn Decareaux and Mayor Rusty Hamilton both contacted Jewish institutions in the region in the hopes of spurring preservation efforts, and eventually Henry S. Jacobs Camp in Utica sent groups to perform upkeep in the early 1990s. In addition to campers, the youth group of Gates of Prayer (in Metairie, Louisiana) made annual trips to the cemetery around the year 2000. Sandy Lassen, president of the greater New Orleans Chevra Kadisha (burial society), led another upkeep effort in 2011. The cemetery remains as the sole evidence of Osyka’s historical Jewish community.

The cemetery gained the attention of local, non-Jewish residents in the 1970s. Lynn Decareaux and Mayor Rusty Hamilton both contacted Jewish institutions in the region in the hopes of spurring preservation efforts, and eventually Henry S. Jacobs Camp in Utica sent groups to perform upkeep in the early 1990s. In addition to campers, the youth group of Gates of Prayer (in Metairie, Louisiana) made annual trips to the cemetery around the year 2000. Sandy Lassen, president of the greater New Orleans Chevra Kadisha (burial society), led another upkeep effort in 2011. The cemetery remains as the sole evidence of Osyka’s historical Jewish community.

Selected Bibliography

Gilbert, June. “Bits and Pieces: More info on old cemetery.” Enterprise-Journal. Apr. 22, 1992.

"Restoring Osyka’s Jewish Cemetery," Southern Jewish Life, December 28, 2011.

Leman, Bernard. “The Samuel Wolf Family of Osyka, Mississippi,” Manuscripts Department, Tulane University Libraries.

Varnado, Lucy (Wall). Osyka: A Memorial History: 1812-1978 (Osyka, 1978).

Gilbert, June. “Bits and Pieces: More info on old cemetery.” Enterprise-Journal. Apr. 22, 1992.

"Restoring Osyka’s Jewish Cemetery," Southern Jewish Life, December 28, 2011.

Leman, Bernard. “The Samuel Wolf Family of Osyka, Mississippi,” Manuscripts Department, Tulane University Libraries.

Varnado, Lucy (Wall). Osyka: A Memorial History: 1812-1978 (Osyka, 1978).