Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities - Woodville, Mississippi

Overview >> Mississippi >> Woodville

Overview

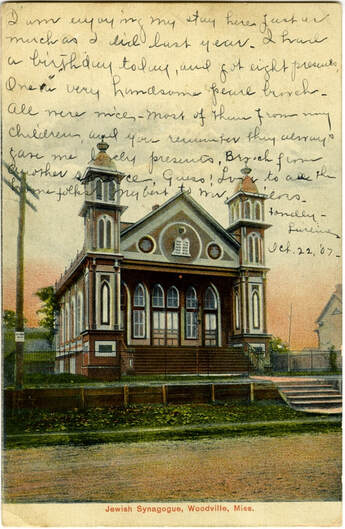

A postcard depicts the second Beth Israel synagogue, c. 1907. Cooper Postcard Collection, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

A postcard depicts the second Beth Israel synagogue, c. 1907. Cooper Postcard Collection, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Woodville is the seat of Wilkinson County, which occupies the southwestern corner of Mississippi. European settlers arrived in the area as they traveled north on the Mississippi River, and Wilkinson County had one of the largest populations when the State of Mississippi came into being in 1809. The county’s early development depended on cotton agriculture and enslaved Black labor. While the county population grew from 10,000 to 16,000 people from 1820 to 1860, so did the proportion of enslaved people, which reached 82 percent (14,467 individuals) by the outbreak of the Civil War.

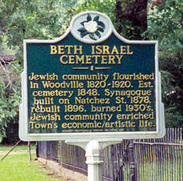

Jewish settlers made their way to Woodville and the surrounding area during the early 19th century but did not establish a communal presence there until mid-century. They organized a Jewish community during Reconstruction, which persisted until the 1920s. By that point the Jewish population had dwindled, in large part due to the decline of the local cotton economy. Although Woodville Jews once played a significant role in the civic and economic life of the town, the only remaining evidence of their presence is the Beth Israel Cemetery.

Jewish settlers made their way to Woodville and the surrounding area during the early 19th century but did not establish a communal presence there until mid-century. They organized a Jewish community during Reconstruction, which persisted until the 1920s. By that point the Jewish population had dwindled, in large part due to the decline of the local cotton economy. Although Woodville Jews once played a significant role in the civic and economic life of the town, the only remaining evidence of their presence is the Beth Israel Cemetery.

Early Jewish Settlers

Jewish peddlers may have stopped in Woodville as early as 1810. In subsequent decades Jewish residents stayed for brief periods. Schoolteacher Charles Lewis arrived in 1828 from Charleston, South Carolina. Levin was acquainted with future Confederate President Jefferson Davis in Woodville, and Davis once served as Levin’s second in a duel. Levin soon left Woodville and later represented Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in the United States Congress. Two other Jews from Charleston—brothers Theodore and Edwin Moise—came to Woodville in 1836. They relocated to New Orleans a few years later, where they gained prominence. Edwin Moise served as speaker of the Louisiana House of Representatives, and Theodore Moise became a well-known portrait painter. After 1830, most Jewish transplants to Woodville immigrated from France and Germany.

According to the research of Elliot Ashkanazi, mid-19th-century Woodville Jews usually stayed for less than a decade. Business and family relationships connected them to New Orleans, and Jewish merchants in Woodville and other rural trade hubs purchased goods (on credit) from Jewish wholesalers there. Michael Simon, a native of the German states, came to Woodville in the mid-1840s and ran a hardware store. In 1850 he opened a dry goods store with his brother-in-law Simon Frank. By 1853 Michael Simon accumulated enough wealth to purchase a small farm that was tended by approximately ten enslaved people. Both Simon and Frank departed Woodville for New Orleans by the end of 1856, although Simon retained an interest in the hardware store until 1860.

The frequent turnover of Woodville’s Jewish merchants mirrored trends across the United States, where Jewish men proved highly mobile in the mid-to-late 19th century. Jewish peddlers and storekeepers sometimes aroused suspicion from local white Christians, who viewed their transience as a mark of potential dishonesty, but, as Ashkenazi points out, successful Jewish businesses tended to familiarize local communities with the figure of the Jewish businessman. Jews could sometimes ameliorate distrust when they showed signs of settling down, especially by purchasing a home or other property. Prior to the emancipation of Black citizens, that property could include enslaved workers, and Woodville Jews including Jacob Schwartz, Isaiah Cohen, Jacob Cohen, and Louis Loeb all enslaved between two and four apiece people in 1860. They also expressed their connection to local white society through military service. Woodville native Gabe Kann served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, as did Solomon Loeb, Joseph Kohn, and several other Jewish residents of Wilkinson County.

According to the research of Elliot Ashkanazi, mid-19th-century Woodville Jews usually stayed for less than a decade. Business and family relationships connected them to New Orleans, and Jewish merchants in Woodville and other rural trade hubs purchased goods (on credit) from Jewish wholesalers there. Michael Simon, a native of the German states, came to Woodville in the mid-1840s and ran a hardware store. In 1850 he opened a dry goods store with his brother-in-law Simon Frank. By 1853 Michael Simon accumulated enough wealth to purchase a small farm that was tended by approximately ten enslaved people. Both Simon and Frank departed Woodville for New Orleans by the end of 1856, although Simon retained an interest in the hardware store until 1860.

The frequent turnover of Woodville’s Jewish merchants mirrored trends across the United States, where Jewish men proved highly mobile in the mid-to-late 19th century. Jewish peddlers and storekeepers sometimes aroused suspicion from local white Christians, who viewed their transience as a mark of potential dishonesty, but, as Ashkenazi points out, successful Jewish businesses tended to familiarize local communities with the figure of the Jewish businessman. Jews could sometimes ameliorate distrust when they showed signs of settling down, especially by purchasing a home or other property. Prior to the emancipation of Black citizens, that property could include enslaved workers, and Woodville Jews including Jacob Schwartz, Isaiah Cohen, Jacob Cohen, and Louis Loeb all enslaved between two and four apiece people in 1860. They also expressed their connection to local white society through military service. Woodville native Gabe Kann served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War, as did Solomon Loeb, Joseph Kohn, and several other Jewish residents of Wilkinson County.

Organized Jewish Life

Jews in Woodville and other small towns could not maintain all of the religious observances of traditional Judaism, but they did not abandon their religious and ethnic identities altogether, either. When Jewish peddler Henry Brugance died in the area in 1848, two fellow peddlers—Jacob Schwartz and Jacob Cohen—purchased a plot to provide him with a Jewish burial. That site later served as the cemetery for the Jewish community. Local Jews also may have held lay-led religious services in the 1850s.

Despite signs of communal activity, high turnover and the disruption of the Civil War years delayed the establishment of formal Jewish organizations until the late 1860s, when local Jews founded the Woodville Hebrew Educational Association. In 1873 they hired Emanuel Rosenfelder to teach school for a mixed class of Jewish and non-Jewish students and to provide religious leadership. Rosenfelder, who later served Temple B’nai Israel in Natchez, only remained in Woodville for a year. In 1878 the congregation built a synagogue on the corner of Banks and Natchez Streets and received a new charter as Congregation Beth Israel.

The most notable development in local Jewish life during Congregation Beth Israel’s first decade was the hiring of Rabbi Henry Cohen in 1885. Although Rabbi Cohen served the congregation for just three years, he left a lasting impression. In 1924 the Woodville Republican proclaimed that “no minister who ever served a church in Woodville was more popular than was Rabbi Henry Cohen.” He encouraged religious observance among his congregants, a challenging feat in the small, rural community. Most Jewish men in the area worked as merchants, which required them to open their businesses on Saturdays, the Jewish sabbath. Rabbi Cohen convinced members to delay opening their stores until after the conclusion of Saturday morning services. The rabbi also developed a reputation for his compelling oratory skills, and local non-Jews sometimes attended synagogue to hear him speak. In 1888 Rabbi Cohen left Woodville to assume the pulpit at Temple B’nai Israel in Galveston, Texas, where he served for more than 60 years and earned further acclaim.

Despite signs of communal activity, high turnover and the disruption of the Civil War years delayed the establishment of formal Jewish organizations until the late 1860s, when local Jews founded the Woodville Hebrew Educational Association. In 1873 they hired Emanuel Rosenfelder to teach school for a mixed class of Jewish and non-Jewish students and to provide religious leadership. Rosenfelder, who later served Temple B’nai Israel in Natchez, only remained in Woodville for a year. In 1878 the congregation built a synagogue on the corner of Banks and Natchez Streets and received a new charter as Congregation Beth Israel.

The most notable development in local Jewish life during Congregation Beth Israel’s first decade was the hiring of Rabbi Henry Cohen in 1885. Although Rabbi Cohen served the congregation for just three years, he left a lasting impression. In 1924 the Woodville Republican proclaimed that “no minister who ever served a church in Woodville was more popular than was Rabbi Henry Cohen.” He encouraged religious observance among his congregants, a challenging feat in the small, rural community. Most Jewish men in the area worked as merchants, which required them to open their businesses on Saturdays, the Jewish sabbath. Rabbi Cohen convinced members to delay opening their stores until after the conclusion of Saturday morning services. The rabbi also developed a reputation for his compelling oratory skills, and local non-Jews sometimes attended synagogue to hear him speak. In 1888 Rabbi Cohen left Woodville to assume the pulpit at Temple B’nai Israel in Galveston, Texas, where he served for more than 60 years and earned further acclaim.

Civic and Business Life

Whereas many Jewish Woodville residents in the mid-19th century came and went within a decade, the establishment of Jewish institutions coincided with the development of a somewhat more rooted Jewish population. Jacob Schwartz’s son Leon made his living as a merchant and served in city government for many years. Cemetery records indicate that multiple generations of families such as the Browns, Cohens, and Myers lived in the area as well.

Several of Woodville’s Jews became prominent in civic affairs. When the local newspaper published 56 biographical sketches of business and civic leaders in 1904, 12 of the entries featured Jewish men. German immigrant Morris Rothschild, for example, arrived in 1880. He eventually owned a dry goods store and a cotton warehouse, and he served as vice president of the Bank of Woodville and Secretary of the local school board. Lee Schloss published a short-lived local newspaper, the Woodville Courier, and later served as president of the school board, city council member, and city treasurer. When the Rosenwald Fund gave money to build a school for African Americans in Woodville, it was named the Schloss-Rosenwald school.

Several of Woodville’s Jews became prominent in civic affairs. When the local newspaper published 56 biographical sketches of business and civic leaders in 1904, 12 of the entries featured Jewish men. German immigrant Morris Rothschild, for example, arrived in 1880. He eventually owned a dry goods store and a cotton warehouse, and he served as vice president of the Bank of Woodville and Secretary of the local school board. Lee Schloss published a short-lived local newspaper, the Woodville Courier, and later served as president of the school board, city council member, and city treasurer. When the Rosenwald Fund gave money to build a school for African Americans in Woodville, it was named the Schloss-Rosenwald school.

The Early 20th Century

The outlook for Jewish life in Woodville remained strong in the 1890s. When the Beth Israel synagogue building burned in 1896, local Jews replaced it with a larger and more impressive building. They also constructed a small religious school building behind the temple and maintained a parsonage for the rabbi next door.

Woodville’s Jewish population suffered a sharp decline in the early decades of the new century, however. Like their counterparts in Summit, Osyka, and even the larger city of Natchez, Jews in Woodville found that the mercantile pursuits which had sustained them in the mid-to-late 19th century brought diminishing profits after the arrival of the boll weevil decimated an already precarious, cotton-dependent local economy. The general population of Wilkinson County dropped as well, from more than 21,000 individuals in 1900 to fewer than 14,000 in 1930.

Woodville’s Jewish population suffered a sharp decline in the early decades of the new century, however. Like their counterparts in Summit, Osyka, and even the larger city of Natchez, Jews in Woodville found that the mercantile pursuits which had sustained them in the mid-to-late 19th century brought diminishing profits after the arrival of the boll weevil decimated an already precarious, cotton-dependent local economy. The general population of Wilkinson County dropped as well, from more than 21,000 individuals in 1900 to fewer than 14,000 in 1930.

By the mid-1920s, Beth Israel no longer employed a rabbi or held regular religious services, and the remaining members sold the synagogue. The building was moved to main street, where it served as a theater until it burned down in the 1930s. The local Jewish population continued to dwindle in subsequent decades, and the final burial at Beth Israel Cemetery took place in 1973. The cemetery fell into disrepair sometime in the early 21st century, but in April 2022 the Woodville Civic Club announced a new Friends of Beth Israel Cemetery fund that will help pay for upkeep at the site.

Selected Bibliography

Ashkenazi, Elliott. The Business of Jews in Louisiana, 1840-1875. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1988, chapter 5.

Oates, Marsha (editor). Jewish Life in Wilkinson County, 1820-1920: Views of a Vanished Community. Woodville: The Wilkinson County Museum, 1995.

Turitz , Leo E. and Evelyn Turitz. Jews in Early Mississippi. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1983.

Oates, Marsha (editor). Jewish Life in Wilkinson County, 1820-1920: Views of a Vanished Community. Woodville: The Wilkinson County Museum, 1995.

Turitz , Leo E. and Evelyn Turitz. Jews in Early Mississippi. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1983.